CHAPTER 1

THE AUTHORITY’S DECISION TO BEGIN CONSTRUCTION BEFORE COMPLETING PROPER PLANNING LED TO COST OVERRUNS AND DELAYS

Chapter Summary

After years of planning for a fully dedicated high‑speed rail system, mounting costs led the Authority to decide instead to use existing infrastructure wherever possible—a cost control technique known as blending. Blending requires lower train speeds and imposes other service limitations, but the Authority will not know the full effect of these limitations until service planning and operations begin. Although blending has resulted in significant projected savings, those savings have only partially offset cost overruns. Further, potential time savings from reduced construction needs will be at least partially offset by the years that the Authority spent studying the dedicated options rather than pursuing blended options. The Authority has now exhausted every major opportunity available to share infrastructure with existing rail systems; thus, sharing infrastructure no longer represents a source of future cost savings.

The Authority's decision to begin construction despite not having sufficiently accounted for known risks contributed to its significant cost overruns. The Authority told us it decided to proceed with construction because it was concerned about deadlines for using $2.6 billion in federal grant funds. However, the risks in question—not having acquired the land to build on, a lack of agreements with existing utility systems, and uncertainty about the requirements that external stakeholders might impose—manifested in changes to its construction contracts that have thus far increased the three current construction projects' costs by more than $600 million. Further, the Authority estimates that it will need an additional $1.6 billion in contract changes to finish these three projects, pushing its total cost overruns above $2 billion.

The contract changes have also resulted in significant time delays, and consequently the Authority has had to continually extend the projects' expected completion dates, pushing them back from 2018 to March 2022. Even with the extended schedules, construction will need to proceed much faster than it has to date for the Authority to meet the federal government's construction completion deadline of December 2022. If the Authority misses this deadline, the federal government could require it to repay the grant funds it received; therefore, it is vital that the Authority do all it can to ensure its time and cost projections are accurate so that it can detect and address any further risks. Moreover, as it moves forward with the construction of the rest of the system, the Authority must take steps to ensure that it does not repeat the types of decisions that led to its significant cost and time overruns to date.

After Years of Planning a Dedicated High‑Speed Rail System, the Authority Has Now Pursued Every Option to Reduce Costs by Using Existing Infrastructure

By incrementally modifying its plans for the high‑speed rail system, the Authority reduced planned costs for some segments. However, these cost savings have also resulted in decreased service capabilities. When the Authority elects to blend a segment of the system by sharing existing rail corridor owned by another railroad, it significantly reduces planned costs by limiting the preparation needed to lay track. However, the Federal Railroad Administration sets a speed limit of 125 miles per hour for high‑speed trains sharing a corridor or track with other rail traffic and of 110 miles per hour limit if the tracks intersect roads, which can be avoided by elevating tracks over or tunneling under roads. These blended segment speeds are significantly lower than those for dedicated high‑speed segments of the system, where regulations allow speeds up to 220 miles per hour.

Further, sharing track means that high‑speed rail trains must split time on the tracks with other operators, limiting how frequently high‑speed trains can operate on a segment. For example, on the San Francisco Peninsula, sharing tracks with Caltrain means that the Authority can only operate four high‑speed trains per hour, instead of 12 per hour, as it originally planned. The Authority similarly plans to share track between Burbank and Los Angeles with Metrolink, Amtrak, and Union Pacific Railroad (Union Pacific). Figure 5 shows how these limitations will affect eventual service options for the three segments where the Authority has implemented blending: San Francisco to San Jose, San Jose to Gilroy, and Burbank to Los Angeles.

Although blending will impose limitations on eventual high‑speed rail operations, the extent to which the limitations will negatively affect actual rail service is not yet clear. According to the Authority's deputy chief of rail operations, one reason why the limitations are not yet known is that service decisions, such as how fast and how frequently to operate the trains, have not yet been determined by the private sector operator that the Authority will select to run the system. Until the operator decides how many trains are needed, the Authority will not know the effect of sharing track. Similarly, although reducing speed limits imposes a restriction with which the train operator must contend, other service considerations also will influence how fast the operator will run the trains. For example, the distance necessary to safely accelerate or decelerate high‑speed trains means that the trains may not be able to operate at 220 miles per hour in parts of the system even if speed limits allow it because of the need to navigate curves and stop in stations.

Figure 5

The Authority Has Adopted Blending in Three Segments

Source: Review of the Authority's business plans, capital cost basis of estimate reports, preliminary and supplemental alternative analysis reports, preliminary engineering for project design reports, service planning studies, and additional cost estimates provided by Authority staff.

* Maximum speed limit shown; speed limited to 140 miles per hour in some segments.

† The Authority stated that it plans to run 12 trains per hour on this segment but did not provide us with any studies or agreements showing how it will accomplish this number.

We attempted to identify how the new speed limits have affected the Authority's projections of the blended segments' travel times, but the Authority was largely unable to provide any supporting documentation for the travel times it projected for these segments before 2016. Because the Authority had already implemented much of the system blending by then, it was generally unable to demonstrate how much time blending added to its travel time estimates. One exception was the segment between San Jose and Gilroy, for which the Authority did not adopt blending until 2018. For this forty‑mile segment, the projected travel time increased from fourteen to eighteen minutes when the Authority switched from a dedicated line to shared track, decreasing the maximum speed for this segment.

Blending has allowed the Authority to expedite the system's planned time for construction by eliminating the time needed to design and build tunnels, viaducts, and other dedicated infrastructure, but the effect of those time savings may be offset by the Authority's past decisions to continue to study dedicated options. Rather than adopting a blended model for as much of the system as possible early on, the Authority has incrementally accepted blended alternatives over the past six years. As of 2012, the Authority planned to construct two new, dedicated tracks, including tunnels and viaducts, between San Jose and San Francisco. Rising cost estimates for this section contributed to the $98 billion system cost the Authority reported in its draft 2012 business plan. To address the rising costs and local governments' concerns about the potential impacts to environmental and community resources on the Peninsula, the Authority proposed a blended model in its revised plan. Shortly thereafter, the State Legislature mandated for this segment that the Authority could not use state funds to expand beyond Caltrain's existing tracks in the corridor. In its revised 2012 business plan, the Authority reported the segment's estimated costs had decreased from $13.6 billion to $5.6 billion, or 59 percent, after it adopted the blended approach. Table 2 provides the Authority's estimates for the decreased costs of the blended segments, which have partially offset increases in its systemwide cost estimates.

Despite its adoption of the blended model in its 2012 revised business plan for one segment, the Authority continued to study dedicated options for at least two more years and did not begin studying a blended option in Los Angeles until 2015, limiting the time savings it might have realized had it acted more quickly. In 2012, the Authority's original plans for Burbank to Los Angeles called for either a tunnel under central Los Angeles or an aerial viaduct—similar to a bridge—running through it. In its May 2014 analysis document supporting the 2014 business plan, the Authority was still planning for dedicated options including a tunnel, ground‑level track, and viaducts. The Authority did not introduce the blended, shared-track model for this segment in its planning document and business plan until 2016.

| COST | CHANGE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEGMENT | BEFORE | AFTER | AMOUNT | PERCENTAGE |

| San Francisco to San Jose | $13.6 | $5.6 | -$8.0 | -59% |

| San Jose to Gilroy | 4.4 | 2.8 | -1.6 | -36 |

| Burbank to Los Angeles | 2.9 | 1.6 | -1.3 | -45 |

Source: The Authority's published business plans, budgets, and internal planning documents.

Note: This table only reflects cost estimates before and after blending was implemented on each segment in order to demonstrate the effect of blending on costs. Other factors, such as a reduction in the planned number of bridges in a segment, have lowered cost estimates after the implementation of blending.

The Authority's Southern California regional director confirmed that the Authority did not seriously begin studying a blended option for Los Angeles until 2015, when it procured a new planning contractor, and that it waited this long to ensure the blended model would not have unexpected consequences. Additionally, the regional director stated that because very little funding was available during this time period, the Authority could not conduct the study of the blended option. However, the 2012 revised business plan states that the Authority's position is that the system's benefits will be delivered faster through the blended approach. We therefore question why it waited three years to begin studying the blended option in Los Angeles to determine whether it was viable. Had the Authority acted earlier, it could have captured more of the time savings blending represents. For example, the Authority's 2012 decision to use blending on the San Francisco Peninsula has led to construction already beginning in that location. By comparison, the Authority has yet to finalize its planned route between Burbank and Los Angeles.

Although the process took several years, the Authority states it has now adopted blending in every segment of the system where sharing infrastructure is possible. In its 2018 business plan, it indicated for the first time that it intends to blend the segment between San Jose and Gilroy by operating within existing freight corridors and possibly sharing track with other carriers. Because the Authority is already pursuing blending on the San Francisco Peninsula and in Los Angeles, its chief of rail operations asserted that no further blending options are available. Additionally, he stated that travel time requirements mean that the Authority cannot implement additional blended segments even if opportunities become available. State law requires that the system be designed to achieve a nonstop travel time from San Francisco to Los Angeles Union Station of two hours and 40 minutes; according to the Authority's model, the travel time incorporating the current level of blending is expected to be two hours, 36 minutes, and 56 seconds.

Our review similarly noted that the blending of additional segments is unlikely because of characteristics of the remaining segments. For example, the only existing rail line traversing the Tehachapi Mountains in Southern California is a winding freight line built in the 1870s. In the north, where the Authority plans to connect the Central Valley to the Bay Area via the Pacheco Pass, no current rail system exists. In both regions, the Authority plans to pursue complicated tunneling projects that include tunnels over 20 miles long and more than 2,000 feet underground.

Blending has allowed the Authority to partially offset significant cost overruns for the system as a whole. Our analysis shows that the Authority's cost estimates would have increased by 111 percent since the publication of its 2009 business plan had the Authority not implemented blending; instead, overall costs have increased by 81 percent. However, the fact that the Authority has now exhausted all blending options limits its ability to mitigate the effects of future cost overruns through additional blending.

The Authority Has Approved Hundreds of Millions of Dollars’ Worth of Change Orders to Date, Most of Which Were for Changes It Initiated

Changes and additions that the Authority has made to its three active construction contracts in the Central Valley have driven costs significantly higher than it originally projected. The Authority uses the change order process to account for unexpected developments, project delays that generate new contractor costs, and other changes to its construction contracts. The construction contracts allocate a specific dollar amount for each component of a project's design and construction. For any additional work that is not contained in the contract, the Authority must authorize a change order, which assigns a cost for the new work and increases the overall contract value. The Authority may direct a contractor to do additional work through a change order, or the contractor may request a change order for work it identifies as necessary. Change orders can also extend a project's timeline either to allow additional work or to account for delays. To date, the Authority has approved more than $600 million worth of change orders related to the three construction projects in the Central Valley.

The Authority relies on contracted construction oversight firms (oversight firms)—which are responsible for overseeing the construction contracts on behalf of the Authority—to evaluate potential change orders' merits and provide independent estimates of how much they should cost. However, we found that the Authority did not always follow the oversight firms' advice. We reviewed 11 of these change orders with a total value of $38 million and found that the Authority obtained the required levels of management approval before executing each.1 However, in four instances, the Authority approved change orders for dollar amounts that were more than its oversight firms recommended or for work that the oversight firms initially determined was already covered under the contracts.

Specifically, in two of these four change orders, the Authority executed changes for amounts that were greater than the oversight firms recommended. For example, the construction contractor for Project 1 requested more than $21 million for unanticipated bridge construction. The oversight firm disagreed with the contractor, estimating a cost of only $7.4 million. The Authority ultimately authorized a change order for $18.6 million—more than twice the amount the oversight firm recommended. When we discussed with the Authority's director of design and construction why the Authority authorized more than the oversight firm recommended, he stated that the Authority's initial position was that the construction contractor would cover the cost of some of the new work because it should already have been aware of the need for that work. However, he was unable to provide any documentation showing how the Authority determined the higher number was appropriate. In the other change order involving a higher amount than the oversight firm recommended, the Authority authorized an $868,000 change when the oversight firm had recommended only $854,000. The Authority's documentation did not explain why the higher amount was appropriate.

In two other instances, the Authority approved change orders involving work the oversight firms initially determined was already required by the existing contract terms. However, the contract language was undermined by the assumptions that the Authority had made during the bidding process. For example, the contractor for Project 2/3 requested additional compensation for increased costs associated with disconnecting existing utility lines. In response, the oversight firm correctly identified that the contract assigned responsibility for utility disconnection tasks to the contractor, and therefore the contractor bore responsibility for these costs. However, the oversight firm also noted that Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), the utility owner, had begun to charge a fee for disconnections that the Authority had not specified in the information it provided to the construction contractor during the bidding process. As a result, the Authority and the contractor negotiated the issue, and the Authority agreed to a change order of $2.7 million. In this case, the Authority's failure to adequately coordinate with a key external stakeholder before beginning the bidding process undermined its subsequent ability to use the oversight firm to enforce contract terms and limit costs.

In the other case we identified, the oversight firm initially concluded that the construction contractor should bear the cost to redesign a bridge that did not meet Union Pacific's standards. The Authority later approved a change order against this advice because it had not previously executed an agreement with Union Pacific, thereby limiting the contractor's ability to coordinate with the railroad. We discuss this change order in greater detail later in this chapter.

We found that the majority of all executed change orders came at the request of the Authority rather than the request of the contractors. Some of these change orders were the result of fundamental changes to the construction projects' plans. For example, the Authority requested and executed a $153 million change order to extend one of the projects 2.7 miles north to connect to the Madera County Amtrak station. Because the Authority did not include this work in the original contract, it clearly required a change order. However, as we discuss in the following section, the Authority requested many other changes that were not the result of fundamental changes to the planned system, but rather related to its decision to begin construction before completing critical tasks.

The Authority Did Not Sufficiently Account for Known Risks in Its Initial Cost Estimates

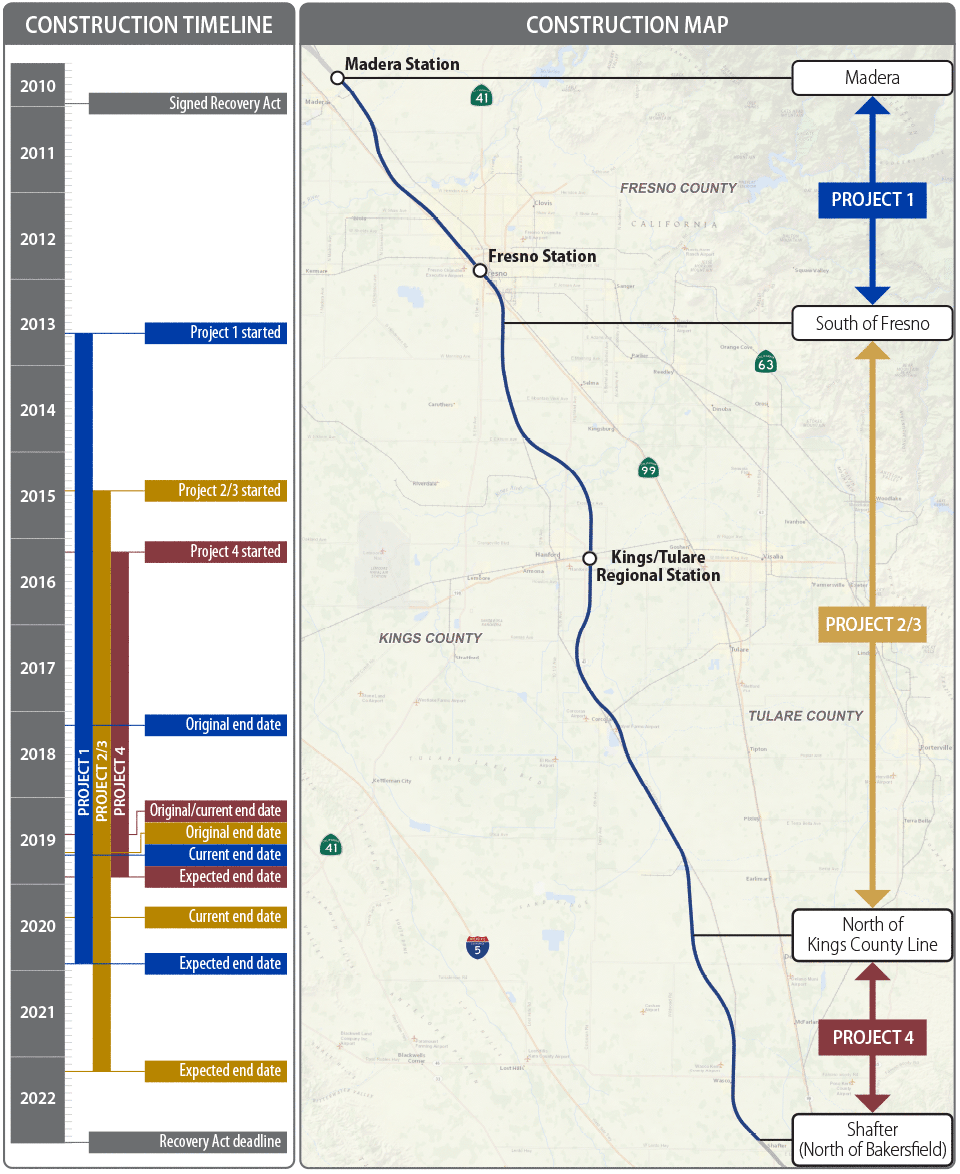

The Authority approved the start of construction in the Central Valley in 2013 despite knowing that moving forward was likely premature from a planning perspective and thus carried significant risks for unknown costs. According to its chief engineer, the primary factor in the Authority's decision to execute a construction contract in August 2013 was to meet deadlines for project completion and spending of funds under the terms of its 2010 grant agreement with the federal government. The agreement provided $2.6 billion for the project under the Recovery Act. Because the purpose of the Recovery Act was to create and preserve jobs and revitalize state and local economies, the agreement required that the Authority complete the Central Valley construction by 2017.2 In coordination with the federal government, the Authority determined that it needed to begin construction as soon as possible to meet that deadline. Therefore, the Authority executed its first construction contract in August 2013 and authorized the construction contractor to begin work in October 2013. Figure 6 details the three projects currently underway—all of which are funded in part by federal money—and provides a timeline of Central Valley construction.

Figure 6

The Authority's Three Current Construction Projects Have Been Phased In but Share a Deadline

Source: The Authority's contracts, business plans, baseline schedules, and maps.

The Authority did not complete many critical planning tasks before beginning construction, which ultimately resulted in significant delays and led to increased costs. Because the Authority's planning was incomplete, it has used change orders to direct its contractors to perform additional work and to compensate them for delays. Quantifying the total cost of the change orders resulting from the Authority's insufficient planning is difficult, largely because the Authority's change order summaries do not show which changes stemmed from the early start of construction. However, the majority of the change order costs relate to risk areas that the Authority had identified but not effectively quantified when it decided to move forward with construction. Some of these risks, such as not securing the property on which it intended to build, directly led to cost overruns and project delays. In other instances, the Authority did not sufficiently account for the costs arising from issues it knew it would eventually need to address, such as relocating utility infrastructure from project sites and addressing the concerns of external stakeholders. At the time, it indicated that it did not have the information or finalized agreements it needed to plan or budget for the mitigation of these issues. Figure 7 summarizes the total impact that executed change orders have had on the three current construction projects in terms of cost and delay.

Figure 7

The Authority’s Change Orders Have Increased the Cost and Length of Its Construction Contracts

Source: The Authority's change order records and construction contracts.

Land Acquisitions

The Authority's decision to enter construction contracts despite not owning the required land—as well as its subsequent inability to acquire land on schedule—directly resulted in delays to the construction schedules. These delays in turn led to additional costs related to labor, materials, and equipment under contract but not in use. The Authority's acquisition of the land was delayed in part by a 2011 lawsuit over whether the Authority had met legal requirements to issue bonds, which the Authority stated it needed to do in order to purchase property. Despite knowing that the lawsuit could restrict access to its funds, the Authority still initiated the request for proposals for Project 1 in March 2012 and executed its first construction contract in August 2013. In fact, the Authority signed the contract the same day that the superior court ruled against the Authority—effectively freezing its bond funds. Although the superior court's decision was eventually overturned, the delay significantly set back the construction contractor's schedule. Land acquisition delays have cost $64 million for Project 1 and extended its completion deadline by 17 months. The Authority also issued change orders because of land acquisition delays in Project 2/3 and Project 4. In total, these change orders have resulted in more than $115 million in additional costs.

Utility Infrastructure Relocations

The Authority also proceeded with construction in the Central Valley without completing agreements with utility companies or ensuring it had a full understanding of the magnitude of the utility infrastructure that it would need to relocate or how it would relocate those utilities. As a result, it could not properly budget for these costs. For example, the Authority originally expected to directly pay utility providers, such as PG&E and AT&T Inc., to relocate utilities for Project 1's planned sites before construction, and it set aside nearly $69 million for this work. However, the Authority later determined the utilities would not be able to complete the relocations in time to meet construction deadlines, and in June 2015, it reassigned the work to the construction contractor. In February 2017, the Authority estimated that completing all of this work for Project 1 would ultimately cost $216 million. However, in April 2018, it provided the board with another revised estimate, which projected that costs would rise to $396 million. Unlike delays in land acquisition, the Authority's poor estimates for utility work did not create costs where it might otherwise have had none. However, given that Project 1's original construction contract was for $970 million, we find it concerning that the Authority failed to anticipate what it now expects will be nearly $400 million in additional costs. Had it developed a better understanding of the costs related to relocating utilities before beginning construction, it might have explored ways of mitigating those costs.

For the next project—Project 2/3—the Authority preemptively assigned utility relocations to the construction contractor. However, the Authority still did not execute an agreement with PG&E specifying the distribution of relocation work between the contractor and the utility for over a year after signing the construction contract. As a result, it accounted for this delay, along with delays related to right‑of‑way acquisition and other issues, by approving additional cost and time for the construction contract. The Authority has not had to add time for Project 4, but utility relocations have created additional costs. According to information it provided to us in July 2018, problems with utilities across the three Central Valley projects had already accounted for $215 million in costs not included in the Authority's original budgets. The majority of these costs—$167 million—have come from Project 1, likely because it is the furthest along. Project 2/3 and Project 4 have experienced $29 million and $19 million in additional costs, respectively.

External Stakeholders’ Requirements

The Authority also did not ensure it was fully aware of the requirements that other external stakeholders, such as other railroads, would impose on the three projects. These requirements led to still more costs for which the Authority did not originally budget. For example, the Authority asked construction contractors to bid on Project 1 and in fact began construction before it finalized a coordination agreement with Union Pacific that specified the circumstances under which the construction contractor could build within Union Pacific's right of way. The lack of such an agreement led to the construction contractor incorrectly assuming that it could construct a pillar for a bridge within Union Pacific's right of way. When Union Pacific declined to permit the pillar, the construction contractor argued that the Authority was at fault because it had not previously identified this issue and alerted the construction contractor. Although the Authority initially disagreed, it later agreed to share the costs with the construction contractor, with the Authority's share being $414,000. The lack of an executed agreement was not unique to Union Pacific; in a June 2014 letter to the Authority, the construction contractor for Project 1 noted that the Authority had not executed needed agreements with several other external stakeholders—including two other railroad operators and the city of Fresno—which resulted in delays to the project.

In total, the Authority has approved change orders worth $27 million related to requirements from external stakeholders across the three Central Valley projects, and it anticipates that these extra costs will increase significantly during remaining construction. For example, freight carriers are currently insisting that the Authority construct intrusion protection barriers to prevent freight trains from derailing onto high‑speed rail tracks along certain portions of the Central Valley segment. The Authority has projected that these barriers will cost an additional $315 million.

The Authority Was Aware That Its Early Start to Construction Could Lead to Significant Additional Costs

Although its 2018 business plan asserted that the early start of construction in the Central Valley resulted in unforeseen or underestimated costs, the Authority had long been aware that there were risks associated with its decisions to begin construction without completing key preconstruction tasks and that these decisions could lead to significant additional costs. For example, a plan that consultants prepared for the Authority in 2011 identified land acquisition, utility relocation, and external stakeholder coordination as risks that would require mitigation. Similarly, the Authority's chief engineer confirmed that the Authority knew in 2013 that it had not acquired sufficient land, and although it had a plan to secure the needed land, it also knew that its ability to use its bond funding for that purpose was uncertain because of legal challenges. The Authority noted in a March 2013 report to the Legislature that delays in acquiring property could affect costs and deadlines, and it disclosed in the same report that it had not yet entered into the necessary agreements with utility companies, which could lead to additional costs and delays. The Authority was also aware that it would need to work closely with Union Pacific to coordinate construction work on and around its right‑of‑way, yet the 2013 report noted that it had not yet executed an agreement with the railroad. It acknowledged that if the Authority could not reach such an agreement, design work in progress or already completed might be affected, leading to potentially significant cost increases or schedule delays.

Nonetheless, the Authority did not account for the potential costs of these risks in its estimates until recently. As a result, it reported total cost estimates when beginning construction in 2013 that were unreasonably low. In fact, the Authority's May 2018 business plan was the first to assign costs to known program risks, even though we identified concerns with the Authority's risk management processes in our 2012 audit report.3 In that report, we found that although the Authority had identified risks that could affect the system's cost and schedule—such as the lack of a finalized agreement with Union Pacific—it was not promptly and effectively addressing these risks.

A 2013 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) expressed similar concerns about the Authority's risk management, specifically identifying that the Authority had not completed a risk analysis to determine how the risks it had identified, such as right‑of‑way delays, would affect cost estimates. For example, according to the report, the Authority acknowledged the risk that its acquisition of 100 of 400 properties it needed for construction Project 1 would be delayed. However, the Authority did not include the possible effect of this delay in its reported cost estimates. The GAO consequently determined that the Authority only partially met best practices intended to help ensure the credibility of its cost estimates.

Although the Authority has acknowledged that beginning construction when it did resulted in inaccurate cost estimates and contributed to additional costs, it has not yet taken sufficiently detailed steps to ensure a similar situation does not occur on future segments. For example, the Authority's director of design and construction told us that the Authority planned to address these planning issues at a high level in a new program management plan that it was developing. We reviewed the program management plan, published in October 2018, and confirmed that it discusses the need to ensure land acquisition and utility relocations do not adversely affect construction timelines. However, it does not explain in detail about how the Authority will do so. Similarly, the Authority's recently released comprehensive schedule delineates that these "early work" tasks should begin before the design and construction phase on future segments, but the schedule does not establish specific benchmarks the Authority must achieve before procuring a construction contractor—though we note that the Authority does not plan to procure another construction contractor until 2020.

When discussing the Authority's future plans, its chief engineer stated that the uncertain nature of the Authority's funding makes it continually reliant on the terms of available funding sources. The chief engineer stated that if the Authority were to receive another grant with short timeframes like those of the Recovery Act grant agreement, it might have to reevaluate its plans. He further stated that the decision to begin construction when the Authority did was partially driven by a desire to show visible progress as various groups were trying to stop the program, raising concerns that future external pressures may drive the Authority to make similarly poorly planned decisions again.

Although we acknowledge that the Authority must secure additional funding to complete the high‑speed rail system, we disagree that it should accept similar levels of risk brought on by beginning construction before it adequately performs planning. Looking past the Central Valley, the next planned construction segments, between San Francisco and Gilroy and then over the Pacheco Pass between the South Bay and the Central Valley, will present new challenges beyond what the Authority has faced in the Central Valley, including performing construction in dense urban areas and boring 15 miles of tunnels through the mountains. It is therefore imperative that the Authority formalize the lessons it indicates that it has learned in the Central Valley and that it implement a process to incorporate those lessons into its future planning.

To Complete Construction of Its Three Current Projects, the Authority Believes It Will Need $1.6 Billion in Additional Change Orders and Extended Project Timelines

Baseline estimates that the Authority and its oversight firms provided to us in July 2018 indicate that the Authority will need $1.6 billion in additional change orders to complete the three current construction projects, for an anticipated total cost of $4.7 billion. These changes include additional costs for ongoing activities we discuss in the previous section, such as utility relocation and land acquisition. The $4.7 billion total also includes costs for new activities, such as construction of intrusion protection barriers and efforts to mitigate problems with soil stability in the Central Valley. According to the RDP consultants, who are responsible for coordinating the Authority's estimation process, the new baseline estimates represent a budget—and accompanying timeline—that the Authority believes is achievable and realistic, provided it takes appropriate actions as needed.

Because of these projected changes, the Authority will need to extend its schedule significantly. As of June 2018, the Authority had extended the contract completion dates for Project 1 from 2018 to 2019 and for Project 2/3 from 2019 to 2020. However, given the work needed to complete the anticipated $1.6 billion in additional change orders, the Authority's new baseline schedule indicates that it will need to extend the completion dates once again, with the latest—for Project 2/3—in March 2022. If the work does not progress as quickly as planned or if more changes become necessary, the Authority will likely need to push completion dates further into the future.

Additional delays to the three current construction projects pose their own significant risks for the Authority, which must finish the Central Valley construction by December 2022 to avoid violating its federal grant agreements. The Authority received two federal grants for the Central Valley segment, one under the Recovery Act for $2.6 billion and a second for $929 million. Violating the grant agreements could require the Authority to repay this $3.5 billion in federal grant funds, $2.6 billion of which it reports it has now spent. The Recovery Act grant agreement's deadline has been extended once before—from 2017 to 2022—at the Authority's request. The Authority has not indicated any plans to request a second extension or to request an extension for its other grant, and it has no guarantee it would receive such an extension if it asked. In a legal opinion, the GAO concluded that the federal government could require the State to repay all $2.6 billion of the Recovery Act funds if it determines the Authority has violated the agreement, and it could recover the funds by offsetting any other payments by the federal government to the State. Consequently, the Authority's 2018 business plan listed meeting the December 2022 deadline as its first priority.

Earned Value Analysis

According to the Project Management Institute, earned value analysis is a tool that allows entities to measure the progress of projects and to forecast their total costs and dates of completion.

Planned value: How far along the project work is supposed to be at any given point in the project schedule and cost estimate.

Earned value: Actual progress to date in terms of project schedule and cost.

Source: Project Management Institute.

Meeting the federal deadlines for the Central Valley projects will be challenging and will require construction to occur significantly faster than it has in the past. Figure 8 below illustrates how the Authority's change orders have added more work and extended the construction schedule over time. The Authority uses a project management tool called earned value analysis, which is described in the text box. Figure 8, which is based on this tool, demonstrates the Authority's planned and actual progress on its three projects. Change orders affect the planned schedule (blue line) by increasing the amount of work, which is expressed in terms of cost and time. As a result, the Authority's actual progress (yellow line) needs to accelerate from its historical average for the Authority to complete the three projects by the federal deadline. As the green line that represents the required rate to meet the December 2022 deadline demonstrates, finishing the projects in time will require the Authority to work twice as fast over the next four years as it has since it began construction in 2013. If the Authority continues to work at its current rate, it will not complete all anticipated work until 2027, as the red line in Figure 8 shows. Further, the federal grant requires the Authority to lay track across the segment, a task for which the Authority has not yet procured a contractor. It plans to lay the track concurrently with the current construction projects beginning in 2020.

Figure 8

The Authority Must Double the Rate of Central Valley Construction to Meet the Federal Deadline

Source: Analysis of the Authority's estimates at completion, baseline schedules, construction contracts, monthly invoices, and monthly reports.

Note: This figure only presents information on Projects 1, 2/3, and 4, which cover project infrastructure between Madera and north of Bakersfield.

The Authority's recently adopted schedule predicts that it can finish on time, but only if it effectively monitors and mitigates risks. When presenting the new schedule to its board, the Authority's deputy chief operating officer stated his belief that the Authority can achieve the planned schedule, but he conceded that the approach is "very aggressive." For the Authority to effectively mitigate future problems and accelerate the rate of construction, it must have accurate, realistic information on all the risks it faces. According to the Authority's chief engineer—who oversees risk management for the system—the oversight firms play a significant role in the risk management process. However, as we discuss in detail in the next chapter, the Authority's management of its contracts with the oversight firms has been flawed. Further, when we asked about certain information that the oversight firms had provided through the risk management process, an RDP consultant responsible for managing the schedule stated that the firms' risk assessments were sometimes potentially misleading. He attributed this issue to the Authority not always closely or consistently monitoring the oversight firms.

As the cost overages and delays the Authority has experienced in the Central Valley to date demonstrate, insufficient risk identification and management can have serious implications. If the Authority allows deficiencies in its risk assessment process to continue, it may not properly identify and respond to threats to the system's development. This could in turn prevent the Authority from meeting its December 2022 deadline.

The High‑Speed Rail Project Might Benefit From the Establishment of an Independent Oversight Committee

Our review identified several similarities between the high‑speed rail project and the California Department of Transportation's (Caltrans) Toll Bridge Seismic Retrofit Program (retrofit program), another major transportation infrastructure project our office has evaluated several times. Our past audits noted that the retrofit program—which was tasked with retrofitting or replacing state‑owned toll and highway bridges—had experienced cost overruns in part because of its management's failure to perform adequate risk management to quantify potential cost increases. For example, as we stated in our 2004 report on the retrofit program (Chapter 2, page 43, paragraph II), Caltrans had identified certain risks, but it had not quantified the potential dollar costs until August 2004, when it reported soaring cost estimates to the Legislature. Our current audit identified similar problems with the Authority's failure to effectively account for preconstruction risks in its cost estimates, as we note earlier in this chapter.

In response to these and other concerns with the retrofit program's costs and schedule, the Legislature required that Caltrans and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) create an independent oversight committee to provide program direction, review costs and schedules, and approve significant change orders, which the oversight committee deemed to be those over $1 million. Our most recent audit report on the retrofit program, released in August 2018, concluded that the oversight committee's actions had resulted in $866 million in cost avoidance and savings, as well as the avoidance of seven years of potential delays. As a result, the retrofit program was completed generally on budget. We recommended in that report that the Legislature implement similar oversight committees for other large transportation projects that the State undertakes.

The Authority's efforts to deliver the eventual rail system might benefit from similar additional oversight. That said, differences between the Authority's and retrofit program's governance structures make it unclear exactly what role a high‑speed rail oversight committee would play and which specific public entities should serve on it. Before the implementation of the retrofit project oversight committee, Caltrans managed the program directly. In contrast, the Authority's board, which the Legislature and the Governor appoint, governs the Authority. In 2008 the Legislature also required the Authority to create a peer review group composed of experienced individuals appointed by the state treasurer, state controller, director of finance, and secretary of transportation to review and analyze the Authority's planning, engineering, and financing, and to report its findings to the Legislature. If the Legislature appointed a high‑speed rail oversight committee, it would need to determine how that committee would work with the board and peer review group, as well as which entities would serve on the committee. Not all of the members that served on the retrofit program's oversight committee—the chief executives of Caltrans, the MTC, and the California Transportation Commission—would be appropriate for the high‑speed rail project. Of these entities, the California Transportation Commission could potentially provide additional guidance based on its statewide responsibility to manage transportation improvements. However, Caltrans is a current contractor on the high‑speed rail system, which may limit its ability to provide objective oversight.

Nonetheless, the Authority's history of cost overruns and delays suggests that additional oversight may be warranted, especially considering the impending federal deadline for the Central Valley projects and the funding challenges the Authority faces in completing the system. The Authority has previously set cost estimates and timelines that its board allowed to be revised as challenges arose; an independent oversight committee may be better positioned to push back against changes to help maintain the current schedule and budget in the Central Valley and beyond.

Recommendations

To ensure that the change orders it approves are necessary and that their costs are appropriate, the Authority should adhere to the guidance and estimates the oversight firms provide to it. If the Authority chooses to deviate from the oversight firms' recommendations, it should clearly document why it made those deviations.

Before executing its next construction contract, the Authority should establish formal prerequisites for beginning construction to prevent avoidable cost overruns and project delays. At a minimum, these prerequisites should identify specific benchmarks related to land acquisition, utility agreements and relocations, and agreements with external stakeholders, including impacted local governments and other railroad operators.

To better position itself to complete the three Central Valley projects by the December 2022 federal grant deadline, the Authority should improve its monitoring and evaluation of the oversight firms' risk assessment processes and should take steps to ensure that these processes are consistent across the three projects by May 2019.

To enable policymakers and the public to track the Authority's progress toward meeting the federal grant deadline of December 2022, the Authority should, by January 2019, begin providing quarterly updates to the Legislature detailing the progress of the three Central Valley construction projects using an earned value model that compares construction progress to the projected total completion cost and date. The Authority should base these updates on the most current estimates available.

To ensure that it is adequately prepared if it is unable to meet the federal grant deadline of December 2022, the Authority should, by May 2019, develop a contingency plan for responding to such a scenario.

Footnotes

1 We also reviewed two change orders that the Authority's legal unit settled through a different process. Including these two change orders, the total value of our selection is $139 million. As of June 2018, the Authority had executed more than $600 million in change orders. Go back to text

2 As we discuss later in this chapter, the federal government extended this deadline to December 2022. Go back to text

3 California High-Speed Rail Authority Follow-Up: Although the Authority Addressed Some of Our Prior Concerns, Its Funding Situation Has Become increasingly Risky and the Authority's Weak Oversight Persists, January 2012, Report 2011‑504. Go back to text