Use the following links to jump directly to the Chapter you'd like to view:

Chapter 1

State Water Resources Control Board: A District Engineer Violated Conflict‑of‑Interest Law

Chapter 2

Department of Health Care Services: A Former Licensing Chief Violated Post‑Employment Ethics Restrictions

Chapter 3

California Department of Public Health: It Wasted State Funds When It Failed to Follow Travel Regulations

Chapter 4

California Department of Transportation: Its Failure to Properly Manage a Mobile Home Park Cost the State $314,977

Chapter 5

Department of Parks and Recreation: An Officer Improperly Accepted a Gift From an Entity That Does Business With the State, and His Supervisor Failed to Provide Accurate Direction

Chapter 6

Department of State Hospitals: Napa State Hospital Wasted Funds by Paying More Than Necessary for Dispatch Work

Chapter 7

Department of Parks and Recreation: A Supervisor Misused Her State Cell Phone for Personal Purposes

Chapter 1

STATE WATER RESOURCES CONTROL BOARD:

A DISTRICT ENGINEER VIOLATED CONFLICT‑OF‑INTEREST LAW

CASE I2015‑0849

About the Department

The State Water Resources Control Board’s mission is to preserve, enhance, and restore the quality of California’s water resources and drinking water for the protection of the environment, public health, and all beneficial uses. In July 2014, it created its Division of Drinking Water—which is divided into 24 districts statewide—to house the drinking water program, which regulates public water systems throughout the State.

Before July 2014, the California Department of Public Health oversaw the drinking water program.

Relevant Criteria

Government Code section 87100 prohibits a public official from making or participating in any governmental decision in which she or he has a financial interest.

Government Code section 87103 provides that a public official has a financial interest in a decision if it is reasonably foreseeable that the decision will have a material financial effect on several types of interests, including sources of income of at least $500.

Government Code section 82030 clarifies that, if the income of an official’s spouse is at least $1,000, the spouse’s source of income is also deemed a source of income for the official because he or she has a community property interest in that income.

Before being amended in 2015, California Code of Regulations section 18702.2 provided that "participating in a decision" included advising or making a recommendation, as well as preparing or presenting—without significant intervening substantive review—any report, analysis, or opinion for the purpose of influencing the decision. Although in July 2015, the Fair Political Practices Commission finalized several amendments to the conflict‑of‑interest regulations, we applied the regulations in effect at the times the conduct occurred.

Results in Brief

A district engineer for the State Water Resources Control Board (State Water Board) violated state conflict‑of‑interest law by repeatedly recommending that the State’s drinking water program enter into funding agreements that involved an engineering firm that employed the district engineer's spouse and then approved claims that resulted in this same engineering firm receiving $3.9 million. Specifically, state law prohibited the district engineer from making or participating in any decisions that had a material financial impact on the engineering firm because it was a source of income. However, as an employee of the California Department of Public Health (Public Health) and then of the State Water Board, the district engineer participated in a total of 59 decisions from 2010 through 2015 that involved the engineering firm. Although the district engineer’s supervisors were aware of the spouse’s employment, they did not view the district engineer's participation in the decisions involving the engineering firm as a conflict of interest.

Background

Before July 2014, Public Health administered the drinking water program. At that time, state law transferred the responsibility for the drinking water program, as well as all employees who worked on the program, to the State Water Board. This transfer led the State Water Board to establish the Division of Drinking Water (Drinking Water division). As the administrator of the drinking water program, the Drinking Water division is currently responsible for regulating about 7,500 public water systems throughout the State.

Many of the public water systems that the Drinking Water division regulates need financial assistance when correcting drinking water deficiencies. As a result, the State Water Board’s Division of Financial Assistance (Financial Assistance division) provides state funding for water systems that would otherwise be unable to afford to make critical improvements. These water systems must submit detailed applications for the funding, outlining how they intend to correct their deficiencies. The water systems generally hire engineering firms to assist them in the planning and construction phases of their improvement projects and to act as project managers and agents. As they complete work on the projects, the engineering firms and other contractors generally submit invoices to the water systems, which then submit claims to the State so it can, in turn, pay the contractors. However, the engineering firms sometimes submit their claims to the State on behalf of the water systems. Figure 1 explains the flow of funds and information between the State Water Board, water systems, engineering firms, and other contractors.

Figure 1

Flow of Funds and Information From the State Water Resources Control Board to Engineering Firms*

Source: State Water Resources Control Board staff.

* The Department of Public Health followed the same flow of funds and information when it administered the drinking water program prior to July 2014.

The State Water Board's district engineers lead each of the 24 districts within the Drinking Water division and oversee the districts’ regulatory responsibilities as they relate to the water systems. The district engineers also play an important role in the technical review of the funding applications the water systems submit. They assess the feasibility of proposed projects and recommend whether the State should enter into or amend funding agreements with water districts. In addition, the district engineers provide district approval of the water systems’ claims for payment. The district engineers’ proximity to the projects allows them to know how the projects are progressing and whether the contractors have completed the work.

In carrying out their responsibilities related to the improvement projects, district engineers must participate in making some important decisions. To ensure that public officials make such decisions without bias or regard to personal financial interests, the voters enacted the Political Reform Act of 1974 (Reform Act). The Reform Act and its implementing regulations generally prohibit public officials from making or participating in making governmental decisions in which they know, or have reason to know, that they have financial interests, as we discuss in the text box above. Those who violate the Reform Act can be subjected to monetary fines or criminal penalties.

A District Engineer Violated Conflict‑of‑Interest Law by Participating in Decisions That Affected a Source of Income

The district engineer violated the Reform Act by participating in making numerous decisions from 2010 through 2015 at Public Health and the State Water Board that financially affected the engineering firm that employed the district engineer's spouse. After the engineering firm hired the district engineer’s spouse in 2010, those wages became a source of income for the district engineer because they are considered community property. Because the community property interest in the spouse's wages from the engineering firm exceeded the annual $500 threshold that state law specifies from 2010 through 2015, the Reform Act prohibited the district engineer from making or participating in any decisions that had a material financial effect on the firm within a 12‑month period of having received income through the spouse’s employment.

Despite this prohibition, the district engineer participated in decisions starting in 2010 that had a material financial effect on the engineering firm. Specifically, during the years in question, several public water systems hired the engineering firm to help plan for and carry out water system improvement projects for which they already had or soon would apply for funding from the State. As Table 2, the district engineer eventually participated in 59 decisions that had a material financial effect on the engineering firm, including whether to enter into or amend funding agreements with the water systems who hired the firm and whether to approve the water systems’ claims seeking payment to cover the costs of services the firm provided.

Table 2

The District Engineer's Participation in 59 Decisions That Materially Affected the Engineering Firm

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of State Water Resources Control Board’s project files.

* The district engineer made 41 of the decisions while employed at the California Department of Public Health and 18 of the decisions while employed at the State Water Resources Control Board.

The district engineer’s participation in the decision‑making process included submitting reports, memorandums, and emails containing recommendations regarding the technical features of the proposed projects. To determine whether the Reform Act prohibited the district engineer’s participation, we assessed whether the reports or recommendations the district engineer submitted were accepted without significant review or revisions. We found that, because of the district engineer's technical expertise and proximity to the improvement projects, headquarters staff and division management relied heavily on these recommendations and did not revise or modify them. Therefore, these reports, memorandums, and emails played an important role in the final decisions.

As noted in Table 2, the district engineer recommended that the State enter into funding agreements with three water systems that had hired the engineering firm employing the district engineer's spouse. All three decision‑making processes took place when the district engineer worked at Public Health: one occurred in 2010 and the other two in 2013. Even though the 2010 decision falls outside of the Reform Act’s five‑year statute of limitation for administrative action, we include it to illustrate how long this problem existed. In the three instances, the district engineer submitted reports and memorandums to Public Health management, recommending that the State issue funding agreements to the water systems for roughly $1.4 million, $4.9 million, and $800,000, respectively. Although the State and the individual water systems had not established specific budgets for the engineering firm’s services at the time of the decisions, the district engineer clearly had reason to be aware that the engineering firm would receive a portion of the funds for the services it would provide on the projects. Not long after the district engineer made the recommendations, the State entered into funding agreements with all three water systems. In each instance, the engineering firm acted as a project manager for the improvement projects.

Further, in 2013 the district engineer recommended that Public Health management amend two of the funding agreements. The district engineer's two memorandums recommended that the State increase the funding agreements from $1.4 million to $5 million in the first instance and from $4.9 million to $7.8 million in the second, thus increasing the eventual payments to the engineering firm employing the district engineer's spouse. In both instances, management followed the recommendations.

Finally, from June 2011 through March 2015, the district engineer approved 54 claims that included charges from the engineering firm totaling $3.9 million. Acting in the role of project manager for the water systems, the engineering firm typically submitted these claims directly to the State. The district engineer reviewed the firm’s invoices and made the final determination about whether the firm had performed the work related to the amounts it claimed. The district engineer then forwarded the claims to headquarters staff for final approval. This allowed the State to pay the water systems, which then paid the engineering firm.

Although the District Engineer’s Supervisors Were Aware That the Spouse Worked for the Engineering Firm, They Failed to Identify the Conflict of Interest

The district engineer regularly submitted statements of economic interests to Public Health that included the spouse’s employment with the engineering firm. However, the individuals responsible for reviewing the statements did not identify any potential problems. For example, the district engineer’s first‑level supervisor and second‑level supervisor reviewed these statements and even made special note of the spouse’s employment on the supervisor review transmittal forms. Yet, the supervisors did not identify such employment by the engineering firm as a cause of a potential conflict of interest because they did not believe the employment would impact the district engineer’s work or the decisions in which the district engineer participated. Consequently, neither supervisor addressed the situation with the district engineer or made an attempt to contact Public Health’s legal counsel for advice. Both of the supervisors remained with the drinking water program when it transferred to the State Water Board in July 2014.

Although the decisions in which the district engineer participated had a material financial effect on the engineering firm and violated the Reform Act, we did not find evidence that either the district engineer or the spouse received direct financial benefits from any of the decisions.

Recommendations

To address the district engineer’s conflict of interest and to prevent future occurrences, the State Water Board should take the following actions within 90 days:

- Take appropriate corrective action against the district engineer and the supervisors for their participation in or failure to address the conflict of interest.

- Through training and other appropriate means, take steps to ensure the district engineer and others in similar positions do not participate in decisions involving their own economic interests.

- Provide training to those responsible for reviewing statements of economic interests regarding how to identify conflicts of interests and when to consult with legal counsel.

- Refer this case to the Fair Political Practices Commission (FPPC) so it can determine whether further action is warranted.

Agency Response

The State Water Board agreed with our recommendations and stated that it has taken or will take the following actions with regard to our recommendations:

- It will assess the corrective actions to take against the district engineer and the district engineer's supervisors.

- As part of the transition of the drinking water program from Public Health to the State Water Board, the State Water Board instituted a change so that district engineers and others in similar positions in the Drinking Water division no longer participate in financial assistance contracting decisions or approve invoices for newly approved projects. Instead, staff members within the Financial Assistance division are responsible for these activities. These staff members receive additional training and perform oversight to prevent impermissible conflicts of interest. The State Water Board stated that it plans to update training modules and reemphasize the need to confer with counsel or obtain an opinion from the FPPC before employees perform work related to their own economic interests. It also stated that it is finalizing how its conflict‑of‑interest code will apply to the employees who recently transferred from Public Health, which will ensure more uniform training on ethics and the reporting of economic interests.

- It will institute a best practice to ensure that supervisors review employees’ annual statements of economic interests and consult with legal counsel on a case‑by‑case basis to develop specific strategies to prevent employees from engaging in prohibited activities.

- It will provide a copy of our report to the FPPC for further investigation.

Chapter 2

About the Department

The Department of Health Care Services finances and administers a number of individual health care service delivery programs such as Medi‑Cal and substance abuse treatment services.

Relevant Criteria

Government Code section 87406, subdivision (d), prohibits certain former state employees from acting as compensated agents by making any oral or written communications before their former state agencies if the communications are for the purpose of influencing administrative actions or involving the issuance, awarding, or revocation of licenses for a period of one year after leaving state employment.

Government Code section 91005.5 provides that any person who violates certain provisions of the Political Reform Act of 1974 shall be liable in a civil action for an amount of up to $5,000 per violation.

Government Code section 91000 provides that any person who knowingly or willfully violates the Political Reform Act of 1974 is guilty of a crime punishable as a misdemeanor and may be subject to a fine of up to $10,000.

Government Code section 82019 defines designated employees as individuals whom a state agency has specifically identified in its conflict‑of‑interest code as making, or participating in the making of, decisions that could foreseeably have a material effect on any financial interest.

Government Code section 11146.3 states that all designated employees are required to attend a course at least once every two years on the relevant ethics statutes and regulations that govern the official conduct of state employees.

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH CARE SERVICES:

A FORMER SECTION CHIEF VIOLATED POST‑EMPLOYMENT ETHICS RESTRICTIONS

CASE I2016‑0011

Results in Brief

A former section chief at the Department of Health Care Services (Health Care Services) violated the post‑employment restrictions of the Political Reform Act of 1974 (Reform Act) by frequently contacting Health Care Services in attempts to influence decisions on behalf of his paying clients within one year of leaving state employment.

Background

The Reform Act is the central ethics law that governs state employees. Under the Reform Act, each state agency must adopt a conflict‑of‑interest code that designates certain individuals (designated employees) as those who—because of their potential to participate in, influence, or make governmental decisions—must periodically disclose certain financial interests and must take biennial ethics training. The Reform Act also places restrictions on the post‑employment activities of state employees. Sometimes called the one‑year ban or the revolving door prohibition, one such restriction prohibits certain former state employees, including designated employees, from being paid to communicate with their former agencies in any attempt to influence any action or proceeding for a period of one year after the individuals leave those agencies. The Reform Act has broadly defined these types of improper communications to encompass telephone calls, letters, emails, and meetings, as well as the delivery or sending of any communication if done for the purpose of influencing an action or proceeding, as Figure 2 on the following page shows. In addition, the Reform Act permanently prohibits certain state officials from working on proceedings that they directly participated in while employed by the State.

Figure 2

One‑Year Ban Restrictions

Source: Government Code section 87406, subdivision (d), and the California Code of Regulations, title 2, section 18746.2, subdivision (a).

These provisions are designed to ensure that government officials make governmental decisions that protect the public interest rather than their own financial interests. The post‑employment restrictions of the Reform Act further this purpose by ensuring that those who previously worked in state government do not financially benefit from their prior employment by improperly influencing their former coworkers for financial gain. Individuals who violate the Reform Act are subject to monetary fines or criminal penalties.

The Former Section Chief Repeatedly Violated the One‑Year Ban After He Left State Service

For almost four years before the former section chief left state employment in 2014, he oversaw a section within a division of Health Care Services, supervising almost 30 employees. Before his departure, he announced to staff in his division that he would be working in the private sector helping providers submit applications to the same section of Health Care Services that he was currently supervising. Within a month after leaving state employment, the former section chief began working for a provider, and he almost immediately began to contact his former coworkers at Health Care Services on behalf of his new clients.

In the year that followed, the former section chief repeatedly violated the Reform Act. Specifically, we reviewed 39‑application files at Health Care Services as well as the email accounts of the former section chief’s most frequent contacts at Health Care Services. We found that from December‑2014 through December‑2015—the period when the one‑year ban was in effect—the former section chief made at least 164‑oral or written contacts with staff at Health Care Services on behalf of his clients. Further, because we did not perform an exhaustive search of all section employees’ email accounts, he may have made additional contacts that we did not identify in our review. We also found that he visited Health Care Services as a representative of a client on one occasion during the one‑year period.

Although the communications we found varied in content, the former section chief’s actions generally focused on attempting to influence Health Care Services to process his clients’ applications as quickly as possible. For example, the former section chief contacted his former subordinate employees on several occasions to ask them to expedite their processing of applications. The former section chief was explicit in letting Health Care Services’ employees know that he was contacting them on behalf of his clients: in many contacts, he clearly stated that he had been hired by a specific client and that he was permitted to act on its behalf. Additionally, his email signature block often reflected his role as an employee or consultant for a specific client. All of these communications violated the Reform Act because as a compensated agent, he contacted his former employer in an attempt to influence decisions during the 12 months after he left state employment.

When we spoke to Health Care Services’ management regarding the former section chief’s contacts after he separated from state employment, the upper‑level managers we interviewed all stated that they had received many complaints from staff members asserting that the former section chief was very aggressive and bombarded staff with calls asking for information for his clients that the staff would not normally share with those outside of Health Care Services. As a result of the former section chief’s improper communications, the chief deputy director at Health Care Services placed him on a list prohibiting his entry into any of its facilities as of January 2016.

When we interviewed the former section chief, he confirmed that he regularly took the mandated ethics training that informed him of the post‑employment restrictions for designated employees. He also stated that he was aware of the one‑year ban but did not think it applied to him because he was not the ultimate decision maker on certain issues and because he saw many high‑profile examples in the news of other state employees who left state service to work for entities they previously regulated. When we clarified that the one‑year ban does not necessarily prohibit state employees from working for entities that they previously regulated but does restrict former state employees' ability to have certain types of contacts with their former state employers, the former section chief acknowledged that he had made those types of contacts during the one‑year period after he left Health Care Services.

When we spoke to Health Care Services’ management to determine how they handled the former section chief’s improper contacts, we learned that most of them had not understood the one‑year ban well enough to take appropriate action. In fact, although all of the managers we interviewed asserted that they had taken the mandated ethics training—which discusses the one‑year ban—none of the managers could provide evidence that they had completed the training within the last two years, as state law requires. Although state law did not obligate these managers to inform the former section chief that he was violating the one‑year ban, they would have known that his actions were illegal if they had better understood the ban and its specific limitations. Health Care Services could have then referred the former section chief’s violations to the Fair Political Practices Commission (FPPC), which enforces the Reform Act. Since Health Care Services did not make such a referral, our office will forward the findings of this investigation directly to the FPPC.

Recommendations

To remedy the effects of the former section chief’s improper governmental activities described in this report and to prevent such activities from recurring, Health Care Services should take the following actions:

- Conduct a review of all staff in the former section chief’s division to ensure that all appropriate personnel have completed the required ethics training within the last two years, as state law requires.

- Designate a specific individual within the former section chief’s division to track division staff’s completion of ethics training. Health Care Services should ensure it maintains a copy of the staff’s certificates of completion for five years as required by state law and department policy.

- Develop procedures for handling similar situations should they arise in the future.

Agency Response

Health Care Services reported in July 2016 that it agreed with our recommendations and stated that it intended to implement a corrective action plan for the recommendations.

With regard to our first recommendation, Health Care Services stated that it directed all division managers to review immediately the files of the staff members who directly reported to them to verify that those staff members had current ethics training certificates on file. As of July 2016, Health Care Services asserted that all of its designated division staff, including managers and supervisors, had met the ethics training requirement.

Regarding the second recommendation, Health Care Services stated that as of June 2016, it had designated a training coordinator to track and log all of the former section chief’s division staff members’ mandatory ethics training. In addition, Health Care Services indicated that the staff members’ direct supervisors are responsible for maintaining the completed training certificates in their individual files. It also stated it has directed division managers to maintain their own tracking systems to ensure staff members always comply with all training requirements. However, Health Care Services did not indicate clearly which levels of managers it requires to maintain their own tracking systems. Further, given the subject of this investigation was a former section chief, Health Care Services’ requirement that only division managers maintain completed training certificates may not be sufficient to prevent similar situations from recurring.

Lastly, in reference to our third recommendation, Health Care Services stated that the former section chief’s division is working with Health Care Services’ legal and human resources staff to draft a formal procedure that will identify whom staff should inform if a similar situation arises and that will include the steps and processes staff should follow. Health Care Services stated that it anticipates the division will complete the policy no later than September 2016. It further stated that until the former section chief’s division develops a formal procedure, it will immediately consult with legal and human resources staff should a similar situation arise.

Chapter 3

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH:

IT WASTED STATE FUNDS WHEN IT FAILED TO FOLLOW TRAVEL REGULATIONS

CASE I2015‑0034

About the Department

The California Department of Public Health protects the public from unhealthy and unsafe environments; promotes healthy lifestyles; prevents disease, disability, and premature death; provides or ensures access to quality health services; prepares for and responds to public health emergencies; and produces and disseminates data to inform and evaluate public health status, strategies, and programs.

Relevant Criteria

California Code of Regulations, title 2, section 599.616, subdivision (a), defines an employee's headquarters as either the place where the employee spends the largest portion of his or her regular workdays or working time; the place to which the employee returns on completion of special assignments; or as the place that the California Department of Human Resources may define in special situations.

California Code of Regulations, title 2, section 599.626, subdivision (d), prohibits the reimbursement of employees' expenses arising from their travel between home and headquarters.

California Code of Regulations, title 2, section 599.638, subdivision (a), provides that the authorized officer who maintains responsibility for approving a claim must ascertain the necessity and reasonableness of incurring the expense for which reimbursement is claimed.

California Code of Regulations, title 2, section 599.638, subdivision (e), provides that each employee must show his or her headquarters address and home address on any travel expense claim.

Government Code section 8547.2, subdivision (c), provides that any activity by a state agency or employee that violates any state or federal law or regulation is an improper governmental activity.

Collective Bargaining Unit 19, article 12.1, provides reimbursement for actual, necessary, and appropriate business expenses and travel expenses incurred 50 miles or more from home and headquarters.

Results in Brief

The California Department of Public Health (Public Health) wasted state funds when it failed to enforce proper policies and procedures to ensure that it reimbursed travel in accordance with the applicable state laws. Specifically, for the period we reviewed from July 2012 through March 2016, Public Health reimbursed the commuting expenses of an official from the official’s home in Sonoma County to the official’s headquarters in Sacramento. In total, it reimbursed this official $74,224 in state funds for lodging, meals, incidentals, mileage, and parking related to commuting.

In late 2014, Public Health received an internal complaint alleging that the official was receiving improper travel reimbursements. Subsequently, Public Health retained the legal office of the California Department of Human Resources (CalHR) to investigate whether the reimbursements were proper. CalHR determined that the reimbursements were proper, and consequently Public Health continued to reimburse the official for the commute to Sacramento. However, we determined that CalHR received inaccurate and incomplete information leading to an improper conclusion.

Background

State employees may be required to travel to meet the demands of their jobs or a department’s needs, and the State provides reimbursement for the necessary out‑of‑pocket expenses these employees incur when traveling on official state business. Several state laws govern when an employee should travel, identify what qualifies as a permissible expense, and establish reimbursement rates for certain expenses. Employees request reimbursement by submitting travel expense claims with supporting documents. Travel expense claims must be accurate and must identify the trips’ purposes and the employees’ home and headquarters addresses. In addition, state regulations define headquarters and prohibit reimbursement of any expenses arising from travel between home and headquarters.

To meet this requirement, human resources staff at Public Health typically documents an employee’s headquarters on an internal personnel form, which is linked to Public Health’s time and leave reporting system (leave reporting system) for the employee. In addition, Public Health requires that employees’ supervisors as well as Public Health travel unit staff review travel expense claims before reimbursement. The supervisors review travel claims to ensure that employees’ travel was necessary and reasonable and that the claims are accurate and comply with travel rules and policies. The supervisors sign and approve the claims, then forward them with any receipts to the travel unit for a final review. Travel unit staff ensures that per diem and lodging rates are consistent with the amounts allowed in the employees’ collective bargaining contract, that direct charges are consistent with contract rates, and that supervisors submit the original, signed claims with receipts. Travel unit staff also ensures that the payments are permissible and can question any potentially inappropriate travel claims. If a discrepancy exists between what an employee indicates to be his or her headquarters address on a claim and what the leave reporting system reflects, travel unit staff relies on the address recorded in the leave reporting system because human resources entered this information and it is often more accurate. Once the travel unit approves an employee’s claim, it submits the claim to the State Controller’s Office to process the reimbursement.

In this case, the personnel form and the leave reporting system for the official identified the official’s headquarters as Santa Rosa. However, from July 2012 through December 2015, the official’s travel expense claims showed the official’s home address as the Santa Rosa district office and the official’s headquarters as Sacramento. Since January 2016, the official’s travel expense claims have listed a home address in a different city in Sonoma County and a headquarters address in Santa Rosa.

Public Health Failed to Follow Travel Regulations, Which Led to $74,224 in Improper Reimbursements

In July 2012, Public Health redirected the official from an existing position in Santa Rosa to manage a new office and supervise staff located in Sacramento. Public Health executives initially intended to fill the position using a governor’s exempt appointment but later decided not to use an exempt position because Public Health did not have approval to do so, and instead it redirected the official. Despite the job announcement that advertised the position’s location as Sacramento, the official informally was told that the official’s headquarters would remain in Santa Rosa and that the official would be reimbursed for travel to Sacramento. That same month, the official began submitting travel expense claims for expenses such as lodging, meals and incidentals, mileage, and parking. From July 2012 through March 2016—the nearly four years that we reviewed—Public Health approved the official’s expense claims, reimbursing the official a total of $74,224.

However, we found that the official’s travel reimbursements were not consistent with state laws. As stated in the Background, state regulations prohibit reimbursements for travel between an employee’s home and headquarters, and the regulations define an employee’s headquarters as the location where the employee spends the largest portion of regular workdays. Our review of the official’s time sheets and travel expense claims established that the official spent 64 percent of the time working in Sacramento from January 2013 through March 2016. Further, the official and the official’s immediate supervisor acknowledged that the official spends most of the time in Sacramento, and the staff members that the official supervises are located in Sacramento. Accordingly, Public Health should have designated the official’s headquarters as Sacramento, not Santa Rosa. Thus, any expense reimbursements related to travel from the official’s home in Sonoma County to the official’s headquarters in Sacramento were improper. Table 3 identifies the official’s improper travel reimbursements from July 2012 through March 2016.

Table 3

The Official's Improper Travel Expense Reimbursements From July 2012 Through March 2016

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of the official’s travel expense claims.

* The expenses for 2012 do not include all travel expenses because not all records were available for review.

Public Health Did Not Require or Expect Its Accounting Staff to Look for Travel Patterns That Might Indicate an Improperly Designated Employee Headquarters, and Consequently Staff Approved the Official’s Claims

As we describe in the Background, travel unit staff members review employees’ travel expense claims. However, Public Health has not expected its travel unit employees specifically to evaluate employees’ travel patterns to identify indications of improper headquarters designations and further question whether the employees’ claims may be improper. In fact, both the accounting officer who processed most of the official’s travel claims and the accounting officer’s supervisor stated that if employees’ supervisors had signed their travel claims, the accounting staff assumed that the travel was allowable.

Had the accounting officer responsible for reviewing the official’s travel claims been expected to look for indications of improper travel, Public Health might have discontinued its improper reimbursements long ago. Public Health assigns each travel unit employee to process a specific group of employees' travel claims. Consequently, travel unit employees arguably are in the best position to notice travel patterns that may indicate improper expenses, such as commute expenses, because they should be familiar with state travel laws and they see all of a particular employee’s travel claims. When we spoke to the accounting officer, she recalled that she asked about a claim that stated the trip’s purpose was “commute to work.” However, because she was expected only to verify the accuracy of the information in the claim rather than ensure that the reimbursements were not commute expenses, she only inquired whether the official’s home address was accurate on the travel claim. Although she acknowledged to us that employees should not be reimbursed for their regular commute expenses, she continued to process these claims because the official’s supervisor had approved them; therefore, she assumed the expenses were allowable.

Although CalHR Concluded That the Official’s Travel Reimbursements Were Proper, Its Conclusion Was Based on Inaccurate and Incomplete Data

In late 2014, Public Health received an internal complaint alleging, among other issues, that it was improperly reimbursing the official for travel between Santa Rosa and Sacramento. As a result, around December 2014, Public Health requested that the CalHR legal office conduct an investigation to determine whether the official’s travel reimbursements were proper. In October 2015, CalHR issued a memorandum to Public Health concluding that the official’s travel reimbursements were proper. Based on CalHR’s conclusion, Public Health continued to reimburse the official for travel to Sacramento. However, when we reviewed CalHR’s analysis and the evidence it used to reach its conclusions, we determined that CalHR used inaccurate and incomplete information and therefore reached an improper conclusion. Because Public Health asserted an attorney‑client relationship with CalHR, we cannot reveal the nature of the information we deem inaccurate and incomplete. However, we have provided our detailed concerns to both agencies.

We subsequently presented our analysis demonstrating that the official spent the majority of time in Sacramento to the CalHR travel manager, whose duties include analyzing travel expenses. He agreed the State appears to be paying for the official’s commute to work. The travel manager stated that he does not believe that the official’s travel is in the best interest of the State and that paying for the official’s commute to work is inconsistent with state policy. In addition, he told us that Internal Revenue Service rules state an employee’s travel to a work location for a period of time beyond one year constitutes a de facto change in the employee’s headquarters. Further, except for a rare exception not applicable in this instance, the travel manager stated that reimbursing an employee for meals and lodging within the 50‑mile area of his or her home or headquarters is always inappropriate. However, if a department determines the travel was allowable, such reimbursements would constitute a taxable fringe benefit because the employee incurred the expenses within the headquarters area.

Recommendations

To remedy the effects of the improper governmental activity identified by this investigation and to prevent similar activities from recurring, Public Health should take the following actions:

- Immediately cease any further reimbursements to the official for travel from Sonoma County to Sacramento.

- Ensure that all Public Health records reflect the official’s headquarters as Sacramento.

- Determine whether it should have reported the official’s reimbursements as a taxable fringe benefit and, if so, amend any relevant tax documents.

- Revise its policies regarding travel expense processing to ensure that its travel unit staff looks for travel patterns and other indications of improper travel expense claims.

- Provide training to all approving supervisors and managers who oversee staff who travel for work purposes to ensure that they understand how to properly determine and establish headquarters locations for their employees.

Agency Response

Public Health agreed with our recommendations and identified the actions it has taken or plans to take regarding each of them. In particular, Public Health reported that effective July 11, 2016, it ceased reimbursing the official for all travel from Sonoma County to Sacramento. In addition, Public Health stated that it will ensure the appropriate records reflect the official’s headquarters as Sacramento. It also stated that it will determine whether it should have reported the official’s reimbursements as a taxable fringe benefit. Further, Public Health stated that it plans to remind managers and supervisors of the importance of determining employees’ headquarters locations and that it will remind staff of procedures to follow when they identify potentially improper travel expense claims. Finally, Public Health stated that it will revise its training to include a reminder of the importance of determining employees’ headquarters locations.

Chapter 4

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION:

ITS FAILURE TO PROPERLY MANAGE A MOBILE HOME PARK COST THE STATE $314,977

CASE I2014‑0934

About the Department

The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) designs, constructs, maintains, and operates California’s highway system as well as the interstate highway system that lies within California. Its Division of Right of Way and Land Surveys acquires and manages property that Caltrans owns in support of its mission.

Relevant Criteria

Caltrans Right of Way Manual section 11.08.02.00 states that a right‑of‑way agent should immediately contact a tenant by telephone or letter if the tenant is delinquent in paying rent.

Caltrans Right of Way Manual section 11.08.03.00 states that if a tenant does not immediately pay rent after the right‑of‑way agent contacts him or her, the right‑of‑way agent should serve the tenant a three‑day notice to pay rent or vacate the property. If a tenant does not pay rent after the three‑day period, the right‑of‑way agent must immediately start eviction proceedings.

Caltrans Right of Way Manual sections 11.04.01.01 and 11.04.02.00 state that right‑of‑way agents should annually perform written analyses of rental rates to ensure that Caltrans is charging its tenants the fair market value.

Results in Brief

The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) failed to properly manage a mobile home park in the San Joaquin Valley that it purchased in September 2010 as part of a project to improve a freeway on‑ramp. As a result of Caltrans’ weak management, the tenants of the mobile home park collectively owed the State $314,977 as of December 31, 2015. Specifically, 16 of the 30 tenants owed a total of $57,142 in overdue rent and late fees. Further, the tenants collectively owed a total of $257,835 in unpaid utility charges. However, Caltrans had not billed the tenants for most of these charges because it had not taken the steps necessary to determine how much each tenant owed. In addition, Caltrans failed to evict two individuals who illegally occupied mobile homes in the park for the last one to two years. Finally, until recently, Caltrans had failed to annually review the monthly rental rate within the park, although its policy and the tenants’ leases require such reviews. We found that Caltrans right‑of‑way agents and their supervisors played significant roles in this five‑year failure to properly manage the mobile home park.

Background

Caltrans’ Division of Right of Way and Land Surveys (Right‑of‑Way division) acquires and manages Caltrans property throughout the State, including property held for future transportation projects, excess properties, and employee housing. In managing these properties, the Right‑of‑Way division often is involved in establishing leases, collecting rent, arranging property maintenance, and terminating leases. The Right‑of‑Way division employees who manage the properties are known as right‑of‑way agents.

As shown in Table 4, we have previously performed investigative and audit work related to the Right‑of‑Way division and its management of contracts and property.

Table 4

Prior California State Auditor Reports Regarding the Division of Right of Way and Land Surveys

| DATE OF REPORT | SUMMARY OF REPORT'S CONTENT | APPROXIMATE COST TO STATE |

|---|---|---|

| August 16, 2012 | The Division of Right of Way and Land Surveys (right‑of‑way division) failed to charge tenants the fair market value for properties associated with its State Route 710 extension project in Los Angeles and Pasadena from July 1, 2007, through December 31, 2011. | $16,700,000 |

| August 27, 2015 | The right‑of‑way division charged telecommunications companies a lower rental rate than identified in their contracts from July 1. 2012, through September 30, 2014. | 883,000 |

Source: California State Auditor Report 2011‑120, California Department of Transportation: Its Poor Management of State Route 710 Extension Project Properties Costs the State Millions of Dollars Annually, Yet State Law Limits the Potential Income From Selling the Properties, August 2012, and Report I2015‑1, Improper Activities by State Agencies and Employees, August 2015.

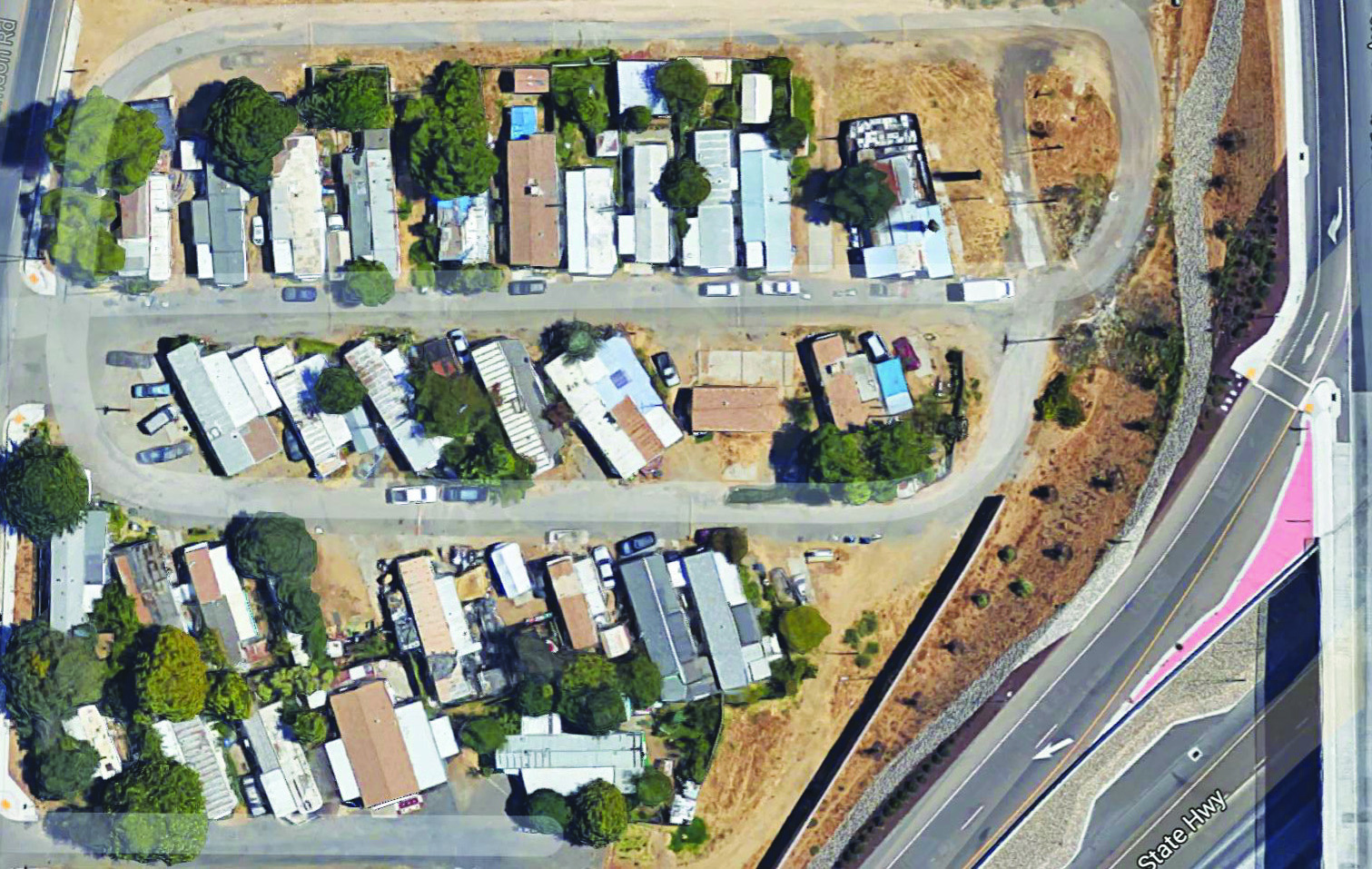

Caltrans’ District 10, one of its 12 districts, has its headquarters in Stockton and encompasses eight counties in central California. In September 2010, Caltrans acquired a mobile home park in District 10 as part of a project to improve a freeway on‑ramp. After Caltrans removed some of the mobile homes within the mobile home park for its construction project, 30 mobile homes remained. Figure 3 shows most of the land that currently constitutes the mobile home park.

Figure 3

Aerial View of the Mobile Home Park

Source: Google Maps.

The tenants of the mobile home park are responsible for paying rent and applicable late fees and for reimbursing Caltrans for the costs of the utilities they use. We found that the leases of 23 of the 30 tenants clearly state that each tenant is responsible for paying $325 in rent each month and a $20 late fee (subsequently modified to $21) if Caltrans does not receive rent by the eleventh day of the month. The leases also state that tenants are responsible for paying for all of the utilities that they use. Caltrans has not required the remaining seven tenants to sign leases, in violation of Caltrans policy. Rather, Caltrans stated that it has oral agreements with these seven tenants that mirror the terms of the written leases with regard to rent, late fees, and utilities.

If a tenant fails to pay rent, Caltrans policy requires the respective right‑of‑way agent to initiate and complete a process that can result in the tenant’s eviction. When a tenant’s rent is past due, Caltrans’ policies require a right‑of‑way agent to first notify the tenant by telephone or letter that the rent is late. If the tenant does not pay the rent immediately, the right‑of‑way agent should serve a three‑day notice demanding that the tenant pay the unpaid rent within three days or vacate the property. If rent is not paid within the three‑day period, the right‑of‑way agent must work with a Caltrans attorney to begin the legal process that could result in eviction. Generally, this process involves providing a 60‑day eviction notice to the tenant.

Caltrans Failed to Collect More Than $57,000 in Rent and Late Fees and Did Not Evict Two Illegal Occupants

Our investigation found that Caltrans failed to collect $57,142 in rent and late fees from the mobile home park’s tenants, and it also failed to evict individuals who illegally occupied two mobile homes. Specifically, as of December 31, 2015, 16 of the mobile home park’s 30 tenants collectively owe Caltrans $53,639 in rent, as Table 5 shows. The Table also demonstrates that four of the tenants, all of whom still live in the mobile home park, owe more than $5,000 each in rent. In fact, one current tenant owes more than $16,000 in rent, the equivalent of not paying rent for more than four years. As of December 31, 2015, Caltrans had also failed to collect $3,503 in late fees from these tenants.

In addition to not collecting $57,142 in rent and late fees, Caltrans did not evict individuals who illegally occupied two mobile homes within the mobile home park. Both individuals applied to become tenants, but Caltrans denied their tenancies because they were unable to demonstrate that they could make rental payments. They nonetheless have occupied the two mobile homes for over a year each, one since August 2014 and the other since June 2015. Although tenants with lease agreements formerly occupied the two mobile homes, Caltrans had taken no action to remove the illegal occupants from the mobile home park during the period we investigated. The individuals’ illegal occupation of two mobile homes had cost the State $7,150 in potential rental revenue as of December 31, 2015.

Table 5

Unpaid Rent by 16 Tenants as of December 31, 2015

Source: California Department of Transportation accounting records and leases.

Caltrans Failed to Obtain Utility Reimbursements From Tenants at a Cost to the State of More Than $257,000

Caltrans also failed to obtain full reimbursements from tenants for the utilities they used. From October 2010 through December 2015, Caltrans paid $342,177 for the electricity, gas, water, sewer, and trash services that the tenants used. Although the tenants’ leases required them to reimburse Caltrans for these costs, they reimbursed Caltrans only $84,342 for all the utilities that they used during this period. Therefore, Caltrans’ failure to obtain utility reimbursements from tenants cost the State $257,835.

Caltrans’ failure to collect utility reimbursements was largely due to the fact that, with the exception of fees for trash services, right‑of‑way agents generally did not send bills to the tenants seeking reimbursement for their utility charges. Caltrans explained that it could not do so because it did not know how much in utilities each tenant had used. Although it employed a private company to read submeters within the mobile home park until January 2011, the private company chose not to renew its contract with Caltrans. Because Caltrans did not replace these services with another contractor, no one has read the submeters since that time. Caltrans stated it had contacted its legal division regarding the options available to address the outstanding billing issue. Regardless, Caltrans could have taken action in recent years. For example, it could have had a right‑of‑way agent or another company read the submeters at the mobile home park during the last five years.

Further, it even failed to seek full reimbursement from tenants for trash services—the one utility for which it consistently charged tenants. Specifically, Caltrans charged tenants $12.50 each month for trash services because the prior owner charged tenants that amount. However, since July 2012, Caltrans has paid the company that provided trash services $717—or about $24 per tenant—each month. Therefore, Caltrans paid almost half of the tenants’ monthly trash service bills for them. When we pointed this out to Caltrans, it admitted its mistake and began efforts to modify its billing for trash services.

Caltrans Had Not Determined the Fair Market Value of the Tenants’ Rental Rate Until Recently

Until June 2016, Caltrans had not conducted a review to determine whether the rent it charges the mobile home park’s tenants reflects the fair market value. Caltrans policy requires, and each tenant’s lease allows, the division to review and adjust rental rates annually. Specifically, Caltrans policy requires right‑of‑way agents to annually perform a written analysis of the rental rate to ensure that Caltrans is charging tenants the fair market value. The right‑of‑way agents should research the rental rates of comparable properties in the area and review other market data, such as the size, location, and condition of properties. Their supervisors should then review and approve the written analysis.

Nevertheless, Caltrans did not conduct such written analyses of the rental rate or increase the rental rate from 2011 through 2015 for any space within the mobile home park. It simply used the $325 per month rental rate that the prior owner charged the tenants in 2010. One of the right‑of‑way agents and one of the supervisors involved with managing the mobile home park stated that they thought Caltrans was going to sell the mobile home park. Therefore, they thought performing a fair market determination would have been a waste of time. In fact, Caltrans did make several attempts to sell the mobile home property, with the last occurring at an auction in July 2015, but no buyers were interested.

In June 2016, nearing the end of our investigation, Caltrans informed us that it had appraised the rental rate at $350 per month, and it provided us the written analysis with which it determined the fair market value. Caltrans based the new rental rate on comparisons with monthly rents at other mobile home parks in the nearby area. Caltrans plans to raise the monthly rental rate for the mobile home park tenants effective September 1, 2016.

Several Caltrans Employees Were Involved in the Failure to Properly Manage the Mobile Home Park

Several Caltrans employees were involved in the failure to properly manage the mobile home park—a failure that ultimately cost the State more than $314,000. Specifically, three right‑of‑way agents were responsible for managing the mobile home park at different times during the five‑year period we reviewed. Each of them dealt with all matters related to its property management, including collecting rent and obtaining reimbursements for utilities. The three supervisors who oversaw the respective right‑of‑way agents during the same period were responsible for ensuring that the right‑of‑way agents adequately performed the property management duties for the mobile home park. Each of the three supervisors was well aware of the problems associated with the mobile home park. For example, two supervisors we contacted indicated that the mobile home park property had numerous problems—including overdue rent, unpaid utilities, illegal squatters, and insufficient trash charges—during the time in which each supervised the property’s assigned right‑of‑way agent. They each told us that managing the mobile home park had taken a disproportionate amount of the right‑of‑way agent’s time. They further stated that the right‑of‑way agents Caltrans assigned to the mobile home park were generally overwhelmed, with more than 400 properties to manage in the district, and that they understood that some things consequently “fell through the cracks” in the mobile home park’s management.

Recommendations

To address the improper governmental activities identified in this report, Caltrans should adhere to the following policies within its Right of Way Manual:

- Pursue rent and utility payments due from the mobile home park’s tenants on a regular and timely basis. This will require that Caltrans develop a means to read the submeters of the mobile home park’s tenants.

- Initiate appropriate collection procedures and, if necessary, eviction procedures for tenants who are delinquent in the payment of rent, utilities, or late fees.

- Immediately begin eviction procedures against the two individuals illegally occupying two mobile homes within the mobile home park.

To further ensure that the improper governmental activities identified in this report do not reoccur, Caltrans should provide training to right‑of‑way agents and their supervisors in District 10 regarding the challenges it faces with this mobile home park.

Agency Response

Caltrans agreed with our recommendations and reported that it planned to implement them by December 31, 2016. In particular, in response to the recommendation that it pursue regular and timely rent and utility payments, Caltrans stated that it has assigned a full‑time right‑of‑way agent to manage the mobile home park to ensure timely actions, payments, and notices. Caltrans also stated that it has provided delinquent tenants with the appropriate notices for payment and that it plans to initiate actions for those tenants who fail to pay.

With regard to our recommendation to initiate appropriate collection procedures and eviction procedures for delinquent rent, utilities, or late fees, Caltrans stated that it began reconciliation of all of the mobile home park tenant accounts and expects to complete its reconciliation by September 1, 2016. In addition, Caltrans stated that as of June 2016, nine tenants had paid their delinquent rent and late fees and are current. It also informed us that the maximum time allowed by civil procedures for collecting past due rents and late fees is 12 months. Caltrans also stated that the city in which the mobile home park is located was reviewing its trash service bill to verify the correct billing amount. Further, Caltrans stated that it had entered into two contracts, one for meter reading and one for billing each tenant based on actual utility use, and that the submeters at the mobile home park were read in July 2016.

In response to the recommendation that Caltrans immediately begin eviction procedures against the two individuals illegally occupying two mobile homes, Caltrans stated it served notices in June 2016 to begin the eviction process.

Regarding our recommendation that Caltrans should provide training to its right‑of‑way agents and their supervisors in this district, Caltrans stated that its legal staff has provided guidance and advice concerning mobile home residency law applicable to the management of the mobile home park. In addition, Caltrans stated that it will develop and provide training about specific mobile home residency laws to appropriate staff and supervisors in the district in September 2016. Caltrans also reported that to reflect guidance on the acquisition, ownership, management, and disposition of mobile home parks, it sent a statewide memorandum on July 29, 2016, and will update its Right of Way Manual by December 31, 2016. Further, Caltrans stated that by September 30, 2016, it plans to distribute a statewide memorandum to update its practices regarding delinquent real property accounts. This memorandum will also identify performance and accountability measures. Moreover, Caltrans reported that it recently began a comprehensive analysis of inventory, rent collection, property inspections, and rent determinations. It stated that it will use the analysis to better identify areas of improvement in the management of its real property statewide and identify properties that it no longer needs.

Finally, Caltrans stated that it is actively pursuing three viable options to dispose of the mobile home park.

Chapter 5

DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION:

AN OFFICER IMPROPERLY ACCEPTED A GIFT FROM AN ENTITY THAT DOES BUSINESS WITH THE STATE, AND HIS SUPERVISOR FAILED TO PROVIDE ADEQUATE DIRECTION

CASE I2015‑0680

About the Department

The Department of Parks and Recreation (State Parks) manages more than 280 parks that contain a diverse collection of natural, cultural, and recreational resources throughout California.

Relevant Criteria

Government Code section 19990 prohibits employees from engaging in any activity that is clearly inconsistent, incompatible, in conflict with, or inimical to their duties as state employees. Specifically, subdivision (f) of this section prohibits state employees from receiving or accepting anything of value from anyone who conducts business with the State.

Government Code section 19572, subdivision (r), states that an employee may be disciplined for violating the prohibitions set forth in section 19990.

State Parks policy instructs employees who receive anything of value from anyone who conducts business with the State to either decline or return the gift and immediately notify the State Parks director.

Results in Brief

We received a complaint alleging that a peace officer supervisor (officer) employed by the Department of Parks and Recreation (State Parks) improperly accepted a gift of 24 pairs of designer sunglasses valued at $4,800 from a vendor that did business with the State. We asked State Parks to investigate this complaint on our behalf and report its findings to us.

State Parks determined that the officer engaged in conduct that was incompatible with his state employment when he accepted the sunglasses from a vendor who conducted business with State Parks. Further, we determined that the officer’s supervisor, a state park superintendent (supervisor), also engaged in conduct that was incompatible with his state employment when—after learning of the gift—he failed to direct the officer to follow State Parks policy and in fact bought a pair of the sunglasses from the officer.

Background

State Parks officers are sometimes required to oversee special events at state beaches. Although private businesses host or sponsor many of these special events, the State pays for the officers to perform their duties. State law and State Parks policy prohibit employees from receiving or accepting gifts from individuals or companies doing business with the State. State Parks policy further instructs employees who receive gifts to either decline or return them and to immediately notify the State Parks director.

An Officer Improperly Accepted a Gift Valued at $4,800 From a Vendor Who Had a Business Relationship With State Parks

The officer engaged in conduct that was incompatible with his state job by accepting a gift of two dozen sunglasses from a vendor who did business with State Parks. The officer oversaw a surfing event at a state beach from late April to early May 2015. Several weeks after the event, the officer received 24 pairs of designer sunglasses from the event sponsor. State Parks estimated that each pair of sunglasses had a retail value of $200, or $4,800 in total. Although State Parks policy required the officer to decline or return the gift and to immediately notify its director, the officer did not take any of these actions.

Instead, the officer accepted the sunglasses and sold them for $20 per pair from his office. When interviewed, the officer asserted that he accepted the sunglasses not as a state employee, but on behalf of a local nonprofit lifeguard association with which employees at the state beach are affiliated. In addition, he stated that he gave all proceeds as a result of the sales to the association, including the remaining unsold sunglasses for the association to use as raffle prizes at a subsequent association banquet. However, State Parks determined that the officer was not an active member of the association at the time and that he did not inform the association of his plan to accept and sell the sunglasses on its behalf. State Parks confirmed that the association received a cash donation of $220—the equivalent of 11 pairs of sunglasses sold at $20 each—around the time the officer claimed. However, State Parks could not confirm the source of the donation or the whereabouts of the remaining 13 pairs of sunglasses, valued at $2,600.

The officer stated that he consulted with his supervisor about what to do with the sunglasses and that they both agreed it would be permissible to sell them and donate the proceeds to the association. However, when interviewed, the supervisor stated that he could not recall if he agreed that it would be acceptable to sell the sunglasses. Instead, he recalled only that he advised the officer to either return the sunglasses, give them to the association, or throw them away. However, the last two options the supervisor suggested—giving the sunglasses to the association or throwing them away—failed to comply with requirements in State Parks’ policy. By accepting the sunglasses, the officer violated both state law and State Parks policy, and by donating the proceeds from the sale, he compounded the problem.

The Supervisor Failed to Ensure His Subordinate Took Appropriate Action After Receiving the Gift

The supervisor also engaged in conduct that was incompatible with his state job when, after learning of the gift to the officer, he failed to direct his subordinate to follow State Parks policy and when he purchased a pair of sunglasses. As stated previously, State Parks policy requires employees to notify the director immediately when they receive anything of value from someone who does business with State Parks. After the supervisor advised the officer to return the sunglasses, throw them away, or give them to the association, he did not notify anyone else, including the director. In fact, instead of taking steps to ensure that the officer followed State Parks policy, the supervisor purchased a pair of sunglasses for a family member. One of the roles of a supervisor is to direct employees to act in accordance with department policy. By giving tacit approval to his subordinate to ignore department policy, the supervisor engaged in an activity that was inconsistent and incompatible with his duties.

Recommendations

To address the improper governmental activities we identified in this report, State Parks should take the following actions:

- Take appropriate corrective or disciplinary action against the officer for failing to follow policy in accepting items of value from a vendor who did business with State Parks.

- Take appropriate corrective or disciplinary action against the supervisor for his failure to properly direct the officer to take appropriate action regarding the sunglasses and for purchasing a pair of the sunglasses.

- Provide training to relevant staff on the appropriate actions to take if they receive something of value from any individual or entity that does business with State Parks.

Agency Response

State Parks agreed with our recommendations and reported that it would take action on each recommendation. Specifically, State Parks stated that it intends to serve the officer with disciplinary action for failing to follow its policy regarding the receipt of gifts. In addition, State Parks stated that it will serve the supervisor with a documented corrective counseling memo for failing to follow its policy regarding the actions to take when a gift is received and for failing to direct his subordinate employee to follow the same policy. Further, State Parks stated that the officer and his supervisor will complete state‑mandated ethics training. Finally, State Parks stated that it will require the officer and the supervisor to review and sign copies of State Parks’ incompatible activity policy. It will keep the signed copies in the officer’s and supervisor’s official personnel files.

Chapter 6

DEPARTMENT OF STATE HOSPITALS:

NAPA STATE HOSPITALS WASTED FUNDS BY PAYING MORE THAN NECESSARY FOR DISPATCH WORK

CASE I2015‑1073

About the Department

The Department of State Hospitals manages the state hospital system, which consists of five state hospitals and three psychiatric centers. The criminal court system can send patients who have committed or have been accused of committing crimes linked to mental illness to one of the facilities.

Relevant Criteria

The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (Fair Labor Act) generally provides for overtime compensation at one and one‑half times an employee's regular rate when the employee works more than 40 hours during a workweek. However, section 207, subdivision (p)(2), of the Fair Labor Act also recognizes that employers should exclude part‑time work from overtime calculations if the work is voluntary, occasional or sporadic, and in a different capacity than an employee’s regular work.

The Code of Federal Regulations, title 29, section 553.30, provides guidance on how to determine whether part‑time work meets the criteria. Specifically, it states that when an employee voluntarily performs occasional or sporadic part‑time work for the same public agency in a different capacity from his or her regular work, the agency should not combine the part‑time hours with the employee’s regular hours to determine overtime. The regulations define occasional or sporadic to mean infrequent, irregular, or occurring in scattered instances.

Section 350 of the State Personnel Board’s Personnel Management Policy and Procedures Manual discusses appointments to an additional position. In particular, an agency can appoint an employee to a distinctly different employment situation than the employee’s initial appointment. An additional appointment typically involves appointment to a position of a different class.

Results in Brief

We received a complaint that Napa State Hospital (hospital) was paying an employee overtime wages based on her regular rate of pay to perform duties typically associated with a different, lower‑paying job classification. We asked the Department of State Hospitals (State Hospitals) to investigate this complaint on our behalf and report its results to us.

We determined that the hospital wasted $2,970 from October 2015 through February 2016 by paying the employee more than she should have received when performing this work.

Background

The employee is an investigator who conducts investigations of violations of laws, rules, and regulations committed on hospital grounds. As an investigator, her hourly pay rate is $39.05. From October 2015 through February 2016, the investigator reported working 187 hours of overtime and received $10,235 in overtime compensation. The hospital generally paid the investigator the overtime rate of 1.5 times her normal rate of pay as an investigator for her overtime hours.2 However, the investigator reported working 111 of those hours of overtime in the hospital’s dispatch center, where she performed duties as a communications operator. This position had a lower hourly pay rate, and its duties did not relate to the employee’s regular job as an investigator.

The federal Fair Labor Standards Act of‑1938 (Fair Labor Act) establishes minimum wage and overtime pay standards affecting employees in the private and public sectors. Under the Fair Labor Act, certain employees who work more than 40‑hours during a workweek are generally entitled to compensation at 1.5‑times the rates at which they are normally paid. However, when those employees perform part‑time work that is voluntary, occasional or sporadic, and in a different capacity from their regular work, they are not entitled to receive time and a half at their regular rates. Instead, the employees should be paid at the regular straight time rates for the job classifications under which they performed the work. For example, in 2008 the U.S. Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division (Wage division) provided an opinion to a public entity regarding the appropriate rate it should pay a detention officer and a patrol officer who each chose to work on an occasional or sporadic part‑time basis as dispatchers. The Wage division advised that “the employer may pay the part‑time rate [of a dispatcher] for the time spent working in the [dispatcher] position, because nothing in the [Fair Labor Act] prohibits an employer from paying an employee at different rates for different types of work so long as no rate is less than the minimum wage.”

The Hours the Investigator Worked as a Communications Operator Did Not Qualify for Overtime

Based on federal regulations and the investigator’s answers to questions about the hospital’s scheduling process, we determined that the work she performed in the hospital’s dispatch center was voluntary, occasional or sporadic, and in a different capacity than that of an investigator. The investigator stated to State Hospitals’ investigators that her work as a communications operator was voluntary and that she had a choice between working overtime to complete her assignments as an investigator or performing work as a communications operator. In addition, the dispatch center’s supervisor posted monthly calendars showing available shifts that needed coverage. Staff members, including the investigator, reviewed the calendars and signed up for shifts solely at their own discretion.

Further, the regulations implementing the Fair Labor Act define occasional or sporadic as “infrequent, irregular, or occurring in scattered instances.” From October 2015 through February 2016, the investigator worked 111 hours over 32 days performing communications operator duties. Figure 4 demonstrates the absence of any common pattern among the dates and hours the investigator chose to work. On some dates, she worked two hours, while on others she worked six hours or more. Additionally, sometimes she worked several days in a row, while at other times she had gaps of longer than a week between shifts

Figure 4

The Daily Hours the Investigator Worked as a Communications Operator

October 16, 2015, Through February 29, 2016

Source: Department of State Hospitals’ analysis of the investigator’s overtime records and dispatch center logs.

* Each column represents the number of hours the investigator worked as a communications operator on an individual day.

Finally, the duties a communications operator performs are in a different capacity than those of an investigator. Based on the California Department of Human Resources (CalHR) class specifications, the duties of an investigator include conducting independent criminal, civil, and administrative investigations; maintaining accurate master investigative case files; and preparing clear, concise, and accurate documents and reports detailing investigative activities and findings. The employee’s regular duties did not include performing dispatch duties. Rather, communications operators—whose positions classifications involve different responsibilities for which they receive a lower hourly wage—perform dispatch duties. Because the investigator voluntarily chose to work occasional or sporadic hours as a communications operator, the hospital should have paid her at the communications operator classification’s regular hourly rate.

The Hospital Wasted $2,970 Overpaying the Investigator

Table 6 shows that the hospital overpaid the investigator $2,970 from October 2015 through February 2016 by paying her as an investigator, mostly at the overtime rate, rather than at the regular hourly rate as a communications operator.

Table 6

The Amount That Napa State Hospital Overpaid to the Investigator for Her Work as a Communications Operator

Source: Department of State Hospitals’ analysis of extra hours the investigator worked as a communications operator based on the investigator’s time sheets and overtime records.

The hospital should have handled this situation appropriately by obtaining a second additional position in which it could have placed the employee when she worked as a communications operator. This approach would have ensured that the hospital properly paid the employee for the hours she worked in the other job classification. In fact, due to limitations of the State’s payroll system, no mechanism existed that would have allowed the hospital to pay the employee the appropriate rate for performing dispatch work other than placing her in an additional position. According to a January 2013 memorandum that CalHR issued, an agency with a critical need to have an employee perform work in a classification in addition to that of his or her regular job should contact a CalHR analyst, who will evaluate the circumstances and determine if the additional appointment is permissible. An executive with responsibility for ensuring adequate staffing levels in the dispatch center failed to contact CalHR and take the steps needed to secure such an additional appointment, which would have allowed the hospital to properly pay the employee in question. As a result, the executive was responsible for the hospital wasting $2,970 by overpaying the investigator’s wages.

Recommendations