The San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission

April 19, 2019

Ms. Elaine M. Howle, CPA

California State Auditor

621 Capitol Mall, Suite 1200

Sacramento, CA 95814

Dear Ms. Howle:

The San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission has reviewed the draft audit report addressing the Commission’s enforcement program and appreciates the opportunity to submit this response.

We appreciate the professionalism of the State Auditor staff and the time they spent trying to understand BCDC’s enforcement program. We also appreciate their recognition of the critical function that BCDC performs regulating development in and around the San Francisco Bay and protecting the Suisun Marsh. We are pleased with the staff’s finding that BCDC generally drafts reasonable permit conditions in compliance with state law and that this is accomplished in a timely manner as required by state law. We are also pleased with the support for our mission and enforcement function that is reflected in the draft report.

Indeed, BCDC plans to use this report to advocate for more resources to allow us to make critical improvements and do more enforcement better. As discussed below, BCDC currently lacks adequate staff and resources to allow it to keep up with the enforcement caseload. We need more people and improved technology, and we intend to pursue these additional resources consistent with the recommendations in the draft report.

We are also pleased that the audit found no support for many of the concerns apparently expressed by some permittees, as reported in the June 29, 2018 letter from the members of the Legislature requesting the audit, including alleged bias on the part of BCDC staff, instances of staff allegedly “moving the goal posts” by changing requirements after permittees worked to satisfy requirements previously set by staff, or a perception of staff as motivated by personal considerations or a desire to add punitive enhancements to fines, rather than achieving the best result for the environment and the public. Similarly, we appreciate that the audit found no evidence that enforcement hearings before the Enforcement Committee and Commission are conducted in a manner that is inconsistent with the Commission’s regulations and that the audit team made no findings that these procedures fail to allow for adequate due process or fail to comply with open-meeting requirements.

The response that follows is organized into three sections. The first section sets forth BCDC’s general comments on the draft audit report. The second section sets forth our responses to the recommendations. The third section sets forth identified issues and corrections to the content of the draft audit report.

Once again, we appreciate this opportunity to respond to Draft Audit Report No. 2018-120. If you have any questions, please contact me.

Sincerely,

LAWRENCE J. GOLDZBAND

Executive Director

RESPONSE

PART I. GENERAL COMMENTS

BCDC has not neglected its mission to protect the Bay and the Suisun Marsh. BCDC acknowledges that it has a growing backlog of enforcement cases that needs to be reduced and that it should update and make more consistent its enforcement processes, and BCDC will use this report to do so. Nonetheless, it is important to emphasize that BCDC has not “neglected” its responsibilities or mission, and the draft report does not argue that BCDC has done so. The sensationalistic first sentence of the introduction and the title of Chapter 1 ignores BCDC's successful implementation of a permitting process that has protected the San Francisco Bay and the Suisun Marsh since the creation of BCDC fifty years ago. The agency has issued thousands of permits and continuously updates its plans and policies to address the most pressing issues impacting the Bay, such as rising sea levels, habitat restoration, environmental justice, and development. BCDC has also been continuously engaged with the public to ensure that activities of varying types comply with state laws and policies and protect the Bay and the public's access to it. As a result of these efforts, the Bay is now larger and healthier than it was fifty years ago and the public has benefitted from hundreds of miles of diverse and open access to the Bay and its unique resources.

In addition, BCDC has led the region – and the nation – in addressing rising sea level and climate change through its planning and permitting activities. In 2011, BCDC was the first coastal management agency in the nation to adopt climate change policies into its coastal management plan requiring projects to conduct a sea level rise risk assessment using the best available science so that projects can adapt to future sea level conditions. BCDC also leads the award-winning Adapting to Rising Tides (ART) program to lead and support multi-sector cross-jurisdictional projects that build local and regional capacity in the San Francisco Bay Area to plan for and implement adaptation responses. Currently BCDC is undertaking the first regional sea level rise vulnerability assessment of the entire Bay Area – Adapting to Rising Tides (ART) Bay Area – integrating transportation systems, vulnerable communities, growth areas, and natural areas into a single analysis. With this initiative, BCDC is poised to lead a collaborative regional effort to develop a regional shoreline adaptation plan.

BCDC is also continuously updating its policies and plans to better reflect and respond to the most important issues facing the Bay. The Commission currently has three major amendments underway: (1) the Fill for Habitat Bay Plan Amendment; (2) the Environmental Justice and Social Equity Bay Plan Amendment; and (3) a major update to the San Francisco Bay Area Seaport Plan. BCDC has expended considerable staff resources addressing the Suisun Marsh Local Protection Program components. This includes: (1) working with the Suisun Resource Conservation District (SRCD) on updating its Suisun Marsh Local Protection Program component, which covers the majority of the Marsh, (2) establishing a digital geo-referenced database of all of the Suisun Marshduck clubs for use by the SRCD and BCDC; and (3) work to process amendments to Solano County's Suisun Marsh Local Protection Program component. Added to this, BCDC operates other ongoing programs on important Bay-wide issues such as regional sediment management, dredging, oil spill prevention and geospatial data, in addition to handling multiple requests for amendments to the Bay Plan.

In sum, protection is not synonymous with enforcement. Protecting the Bay is integral to everything BCDC does in service of the San Francisco Bay Area and the State at-large; and taking into account the thousands of hours that BCDC's Commissioners and staff dedicate to this important work every year, it is simply false to say otherwise. Therefore, a more accurate and fair opening sentence for the report is the last sentence in the first paragraph, which says “. . . . the commission has consistently struggled to perform key responsibilities related to enforcement and has therefore allowed ongoing harm to the Bay.”

It is difficult to comprehensively analyze the Commission's enforcement program and its challenges by focusing primarily on the actions that the Commission has taken since 2012. While BCDC agrees that the enforcement program can be improved and that enforcement should continue to receive greater attention within the agency, an examination of the history of BCDC's enforcement efforts shows that adequate funding for personnel and resources has been a decades-long struggle and that much-needed improvements will be difficult to implement and sustain without increased resources.

The McAteer-Petris Act was amended in the early 1970s to add the existing enforcement authorities, but it was not until 1977 that the Commission received funding to hire its first full-time enforcement analyst. Since then, BCDC's enforcement staff has varied between one and four analysts, with three analysts and a supervisor being the most staff devoted to enforcement in any time period.

It is important to understand BCDC's budget history because, while the report accurately notes that BCDC has a significant case backlog, this backlog was not created in the short time span from 2012 to the present. History also demonstrates that the backlog cannot be effectively eliminated consistent with BCDC's mission if the agency does not request and is not provided with the funds required to enforce the McAteer-Petris Act and the requirements of the permits that BCDC issues.

In 1995, when the Commission examined potential changes to the enforcement regulations as part of Governor Wilson's regulatory reform program, BCDC had one full-time enforcement staff person and approximately 50-70 open enforcement cases. A strategic plan developed in 1998 recommended enlarging the enforcement staff and making improvements to the program. Around this time, BCDC first started using the Bay Fill Clean-up and Abatement Fund to pay enforcement staff salaries, which allowed the Commission to increase the enforcement staff from one to two. Three years later, the Commission adopted a strategic plan that again included a goal of improving BCDC's compliance and enforcement program. After adopting the strategic plan, the Commission created a Compliance and Enforcement Task Force composed of staff and Commissioners charged with reviewing the current practices and regulations and developing proposals to improve the program. This resulted in a number of reforms to both the McAteer-Petris Act and the Commission's regulations, including, in particular, some revisions to the standardized fine regulations in section 11386 of BCDC's regulations.

Around the time the Enforcement Task Force was completing its work, the State also began experiencing budget problems that worsened after September 11, 2001. State agencies were required to implement budget reductions, and these reductions impacted the enforcement staff at BCDC. Later, in 2008, just as BCDC began to increase enforcement staff, the Great Recession and state worker furloughs effectively limited the personnel hours devoted to enforcement.

Fortunately, the Governor and State Legislature approved BCDC's 2018 request to use the Bay Fill Clean-up and Abatement Fund to increase BCDC's enforcement staff. This is enabling the agency to hire both an additional attorney and an enforcement program manager. Under its current leadership, BCDC is making significant strides in prioritizing enforcement and increasing the resources devoted to enforcement. Nonetheless, absent a further increase in available resources, the agency cannot make the important improvements recommended in the report. BCDC estimates that increase to total about $1.5 million annually.

BCDC's current lack of staff resources is hindering its ability to fully achieve its enforcement functions. The draft report states that staffing challenges and staff turnover have exacerbated issues with the enforcement process. A significant component of the recent issues with turnover is the growing market differences between California's coastal areas and the rest of the State. The Commission supports the establishment of a geographic pay compensation system that will allow BCDC to offer compensation that recognizes the difference in the cost of housing in the Bay Area in comparison to Sacramento and the rest of the State. The agency urges that support for this effort be included in the draft report.

The draft report also recommends that the Commission conduct a workforce study. This a valuable recommendation, but, even absent such a study, it is clear that BCDC lacks adequate staff and resources to allow it to eliminate the backlog and fully enforce state law and the conditions of the permits that it issues. As noted in the report, reassigning existing staff would jeopardize other equally important responsibilities. Simply put, improving the enforcement program requires additional personnel and resources totaling approximately $850,000 annually.

Greater emphasis on compliance would be beneficial. The report recognizes the significant amount of time that staff spend attempting to resolve cases amicably and comprehensively before initiating a formal enforcement action. However, as the report notes, staff lack the tools to adequately monitor compliance with permit conditions and address permit violations proactively.

Permits generally require reporting, monitoring, and ongoing maintenance, but without the necessary resources, including both personnel and technology, it is difficult to ensure that all permittees are complying with permit requirements. The limited staff and resources also limit BCDC's ability to resolve issues before they become significant. As noted above, BCDC has recognized for many years that more emphasis on compliance would probably help control the backlog of cases. To do so, BCDC requires more funding to create a permit compliance position to support the enforcement efforts. It also needs the resources to develop a full-scale regulatory (permits, compliance, enforcement) tracking system.

It is also not accurate to state that staff never conduct site visits or undertake patrols of permitted areas in advance of bringing an enforcement action. Site visits occur, but, due to limited time and resources, site visits are typically combined with other activities, such as inspections for developments that are undergoing permitting or visits to other nearby sites that are the subject of an enforcement action. With greater resources, staff could implement procedures to patrol areas and conduct proactive inspections more regularly.

Commissioners continue to provide leadership and guidance. The report states that a lack of management review and oversight by the Commission have contributed to enforcement process problems. BCDC agrees that Commission direction and management oversight are both key to an effective enforcement program. That is why BCDC re-invigorated the Enforcement Committee to resolve major cases and provide policy guidance. While the Commission agrees that the adoption of formal policies and guidance will improve the enforcement program and minimize the risk for error, the Commission does not agree with the statement that it has improperly delegated enforcement duties to staff. It is important to recognize that the standardized fine process, and other processes used to resolve cases at the staff level, are intended to promote prompt and efficient resolution of violations without action by the Commission. BCDC staff will explore additional measures to ensure that the Commission is sufficiently informed of enforcement activities, but one of the objectives of the reforms that BCDC is developing is less, rather than more, burdensome enforcement procedures. It is thus important to ensure that staff are able to continue their work to resolve cases efficiently and short of formal Commission action.

Staff follow regularized procedures for pursuing enforcement and conducting management review but these have not been formalized and are not always documented in the case files. The draft report states in several places that BCDC lacks formal guidance, procedures, and policies that detail critical aspects of the enforcement process. BCDC agrees that several valuable process improvements could be undertaken, including the development of formal policies for describing violations and calculating penalties. Nonetheless, the failure to cite formal procedures should not be interpreted to mean that there are no regularized procedures for commencing and bringing cases forward and that all aspects of BCDC's enforcement efforts lack consistency. The lack of formal processes does not equate to a lack of coherent or regularized processes.

Also, in general, management does review the enforcement cases that are pursued and oversee staff activities. The chief of enforcement and a member of the legal team and/or the regulatory director, as needed, review all letters sent to violators, although these internal staff communications are generally not documented in the case files. Case files are public-facing; therefore, it is inappropriate to include draft versions of documents with reviewer's notes and mark-ups in them. BCDC also has a records retention schedule specifying that these staff notes and internal draft edits should not be retained. Due to the scope of the audit, the auditors did not review cases being actively investigated, which would demonstrate the extensive level of management review that occurs throughout the enforcement process.

BCDC's enforcement efforts are hindered by inadequate information and records management systems. Generally speaking, BCDC agrees with the audit staff's observation that the current enforcement database should be improved. Nonetheless, it is important to recognize the context in which this database exists. As explained to the audit team, largely as a result of resource limitations, BCDC currently relies on information and records management systems that create inefficiencies and reduce staff productivity. These inefficiencies include but are not limited to duplication of effort, lack of remote access to key systems, and a lack of current industry standard tools, forcing staff to spend excessive time on tasks such as filing and searching for records.

In recent years, BCDC has made important improvements to its information management systems. The draft report does not acknowledge that the current database was created in-house with very limited resources, and became operational just days before the audit started. It is a major improvement on the pre-2018 management tools and some limitations on the information in the database are the result of limited staff and time to input the information. Nevertheless, BCDC agrees that its systems should be improved, and these improvements include the acquisition of an industry standard platform that links permitting, compliance, and enforcement case management. Using data provided by other agencies, a preliminary estimated cost for a tool of this nature is, at minimum, $225,000 to install and $40,000 per year to operate. This also would not necessarily replace any costs currently incurred for existing tools, and this does not include various other needed improvements to BCDC's systems, including up to $200,000 annually for additional staff to manage the system. Currently, staff is working with the IT Director of the California Natural Resources Agency to develop a three-year plan to address BCDC's highest priority information technology needs agency-wide.

PART II. RESPONSE TO SPECIFIC RECOMMENDATIONS

I. Suggestions to the Legislature

Require the following by 2020-21:

- Require BCDC to create and implement a procedure to ensure that managers perform documented review of staff decisions in enforcement cases. BCDC agrees that oversight of staff enforcement is important but does not agree that legislative action on this is necessary or appropriate. As noted above, review is generally conducted for all enforcement cases, although this is not always documented in the public-facing enforcement case files. BCDC will explore how to develop more formal procedures and means of documenting review of staff decisions.

- Create timelines for resolving enforcement cases. BCDC agrees that resolving cases in a timely manner is important and that timelines can assist in achieving this objective, but does not agree that legislative action on this is necessary or appropriate. However, in the past, particularly during the regulatory review effort undertaken in the 1990s, the Commission and staff agreed that legislatively-established limitations periods or timelines could jeopardize the Commission's ability to enforce its laws and regulations and remedy violations. BCDC does not agree that legislative action on timelines is necessary, but BCDC is committed, as noted below, to developing policies and procedures to promote the resolution of enforcement cases within targeted timelines.

- Create and implement a penalty matrix for applying fines and penalties. BCDC supports this recommendation but does not agree that legislative action is necessary to implement a penalty matrix. Through a public process, under the guidance of the Commission and Executive Director, staff will commence an effort to develop a matrix and/or policies or regulations to apply to fines and penalties.

- Direct the commission to begin developing regulations by fiscal year 2020-2021 to define single violations. BCDC supports the recommendations for improvements to its enforcement program, but does not agree that a legislative directive to develop regulations is necessary or appropriate, absent a thorough evaluation of the required changes and the best means of implementing these changes. Through a public process, under the guidance of the Commission and the Executive Director, staff will commence an effort to develop regulations and/or policies and guidance that define violations.

- Direct the commission to begin developing regulations to create a method of resolving minor violations through a fine. BCDC supports the recommendation to evaluate regulatory changes that could assist in resolving minor violations more efficiently. Through a public process, with Commission oversight, BCDC will commence an examination of the standardized fines regulations and explore means of ensuring that there is an efficient process for resolving minor violations through a fine.

- To ensure that the commission complies with its duties under the state law related to the Suisun Marsh, the Legislature should require the Commission to report to the Legislature and the public upon completion of its comprehensive review of the marsh plan every five years, beginning with FY 2020-21. BCDC agrees with this recommendation and notes that the Commission adopted, on March 15, 2019, a staff recommendation to undertake a comprehensive review the Marsh Act, Suisun Marsh Protection Plan, and local protection plans, subject to availability of resources and starting with a collaborative meeting of interested agencies and groups. BCDC estimates that, initially, this will require about $465,000 annually.

- To ensure that the commission uses the abatement fund appropriately, the Legislature should clarify that the Clean-up and Abatement Fund's intended use is for physical cleanup of the Bay, rather than enforcement staff salaries. BCDC does not agree that the use of the Bay Fill Clean-up and Abatement Fund is currently limited by statute to physical cleanup actions in the Bay, but would welcome clarification by the Legislature if it is determined that actions to enforce the requirements of the McAteer-Petris Act and BCDC permits do not further the removal of fill or “other remedial cleanup or abatement actions” within the Bay consistent with Government Code § 66647(b). BCDC further notes it may only use funds from the Bay Fill Clean-up and Abatement Fund when appropriated by the Legislature, and thus, starting as early as FY 99-00, BCDC has used the Clean-up and Abatement Fund when necessary to fund all or a portion of enforcement staff salaries with the knowledge of both the Legislature and Department of Finance.

- Consider fully funding enforcement through the General Fund to align revenue sources with the Commission's responsibilities. BCDC supports this recommendation and hopes the Legislature would include additional funding to establish and maintain an effective compliance program. This additional funding should be sufficient to allow BCDC to hire additional people and acquire the technological resources that it needs.

- After the Commission implements the changes noted below, the Legislature should provide the Commission with an additional tool to address violations by amending state law to allow the Commission to record notices of violation on the titles of properties that have been subject to enforcement action. BCDC supports this recommendation and hopes the Legislature would provide the commensurate funding necessary to administer this change. Notably, however, BCDC does not believe that legislation to provide this tool should be delayed. BCDC is committed to improving the enforcement program, and this tool could result in significant improvements to BCDC's ability to manage its caseload.

II. Suggestions to the Commission

The Commission should take the following actions by January 2020:

- Develop and implement procedures to ensure that its management adequately reviews staff enforcement decisions. These procedures should include requirements detailing how staff should document and substantiate violations, case resolutions, and their rationale for imposing fines. The procedures should also include requirements for staff to provide achievable levels of proactive enforcement and site visits. BCDC agrees with the recommendation to develop procedures to detail how violations are documented and substantiated and how cases are resolved and fines are imposed. Staff is exploring how to become more proactive in its enforcement efforts, recognizing, as noted above, that time and resources may limit the ability to engage in regular site visits or other proactive efforts. BCDC will also explore means of furthering management review of enforcement decisions and possibly better documenting the review that is occurring.

- Develop and implement procedures to ensure that staff open, investigate, and close cases in a manner that is consistent with state law and that encourages the responsible use of staff time. BCDC staff actions currently comply with state law. That being said, BCDC agrees with this recommendation. Staff has begun developing and will continue to develop formal procedures to govern the opening, investigation, and closure of cases and will report to the Commission on the development and finalization of these procedures as this process proceeds. The goal of this effort will be to use existing staff time and resources as effectively and efficiently as possible.

- Develop guidance that enumerates the violation types that the commission deems worthy of swift enforcement action, those that staff can defer for a specified amount of time, and those that do not warrant enforcement action or that can be resolved through fines. BCDC agrees with this recommendation and will work to improve its current processes and approach to enforcement case prioritization.

- To help it focus its enforcement efforts on cases with the greatest potential for harming the Bay, the commission should simplify its system for prioritizing its enforcement cases. BCDC agrees with this recommendation in general. However, staff does not agree with the implication that the prioritization tools have been ineffective in assisting enforcement staff in managing their caseloads. Instead, the prioritization tool has provided the Commission with a defined list of the highest priority cases on which staff can focus their limited resources. In addition, staff now has an interactive, public-facing online enforcement report form that allows members of the public or outside organizations to directly input complaint data into BCDC's digital case management system, providing, to the extent the information is known, the location on a map of the Bay, as well as available details to assist in documenting the violation. These tools demonstrate the staff's desire to continue to improve upon the value of the services it delivers to the public, independent of the audit and its findings. As noted above, staff hopes that additional resources will be provided by the Legislature to purchase better tools that can be used to effectively and efficiently assist in case management and prioritization.

- Create a penalty calculation worksheet. The commission should require the worksheet's use for all enforcement actions that will result in fines or penalties, and it should create formal policies, procedures, and criteria to provide staff with guidance on the application of the worksheet. BCDC agrees with this recommendation. Through a public process, with Commission oversight, staff will develop a penalty calculation matrix or similar kind of tool. Staff will also review the standardized fines regulations to determine whether improvements can be made to the regulations governing standardized fines.

- Develop a procedure to identify stale cases. Following the application of this procedure, the commission should seek appropriate settlements for such cases that preserve or exercise the State's legal rights to resolve violations and levy penalties. BCDC agrees with this recommendation. Staff have started to review the current open cases and cases that BCDC is not actively pursuing, with the goal of resolving cases and reducing the backlog.

- Evaluate and update permit fees every five years in accordance with its regulations. BCDC agrees with this recommendation, and BCDC has initiated a process to amend the fees.

- Conduct a comprehensive review of local agency compliance with the marsh plan and issue recommendations as necessary to implement the protections outlined in the Suisun Marsh Preservation Act and its component plans. While BCDC agrees with this recommendation, completing this by January 2020 is not realistic and is inconsistent with the Auditor's recommendation to the Legislature on page 37 of the draft report. As described above, this review will be undertaken consistent with the Commission's direction as adopted at its March 7, 2019 meeting. BCDC recommends moving this recommendation to the list of commission actions required for 2021 and notes that this timeframe is more appropriate in light of the resources and time required to complete a comprehensive review.

- Appoint a new citizens' advisory committee as required by law and determine a schedule for the committee to conduct regular meetings. The Commission recently considered appointing a new Citizens Advisory Committee and determined that doing so is likely unnecessary given the Commission's greatly expanded public outreach efforts during the past six years. The CAC was also never intended to focus on enforcement and likely would provide little benefit in implementing the recommendations in this draft report. While the CAC was an active and valuable voice in the development of the Bay Plan and other initial actions, the Commission recently determined that reactivating it is not a priority given the benefits provided by establishing real-time working groups that provide input on key initiatives. The Commission noted that BCDC has created five Commissioner working groups addressing rising sea level, bay fill, environmental justice and social equity, financing the future, and public education. These have met publicly and engaged both formally and informally with interested stakeholders and the public. The Planning Division has also expanded its public outreach to local governments, private sector interests, and neighborhood and community-based organizations. The Commission is also developing a robust engagement strategy for the Regional Sea Level Rise Adaptation Plan, including forming a multi-sector, cross-jurisdictional advisory committee, as well as a technical committee to advise and guide the Commission's activities.

- To ensure that it uses the abatement fund for the physical cleanup of the Bay, the commission should create a policy by January 2020 identifying the minimum amounts from the Bay Fill Cleanup and Abatement Fund that BCDC will disburse and prioritize the projects that BCDC will support through disbursements to the appropriate entities. As noted above, BCDC does not agree that using the Clean-up and Abatement fund to pay enforcement staff salaries does not comply with the intent of section 66647(b) of the McAteer-Petris Act. Nonetheless, BCDC will explore how best to disburse funds, provided that such disbursement does not jeopardize the ability to staff and implement a robust enforcement effort.

To build on prior recommendations and ensure that it maximizes the effectiveness of its enforcement program, the commission should take the following actions by January 2021:

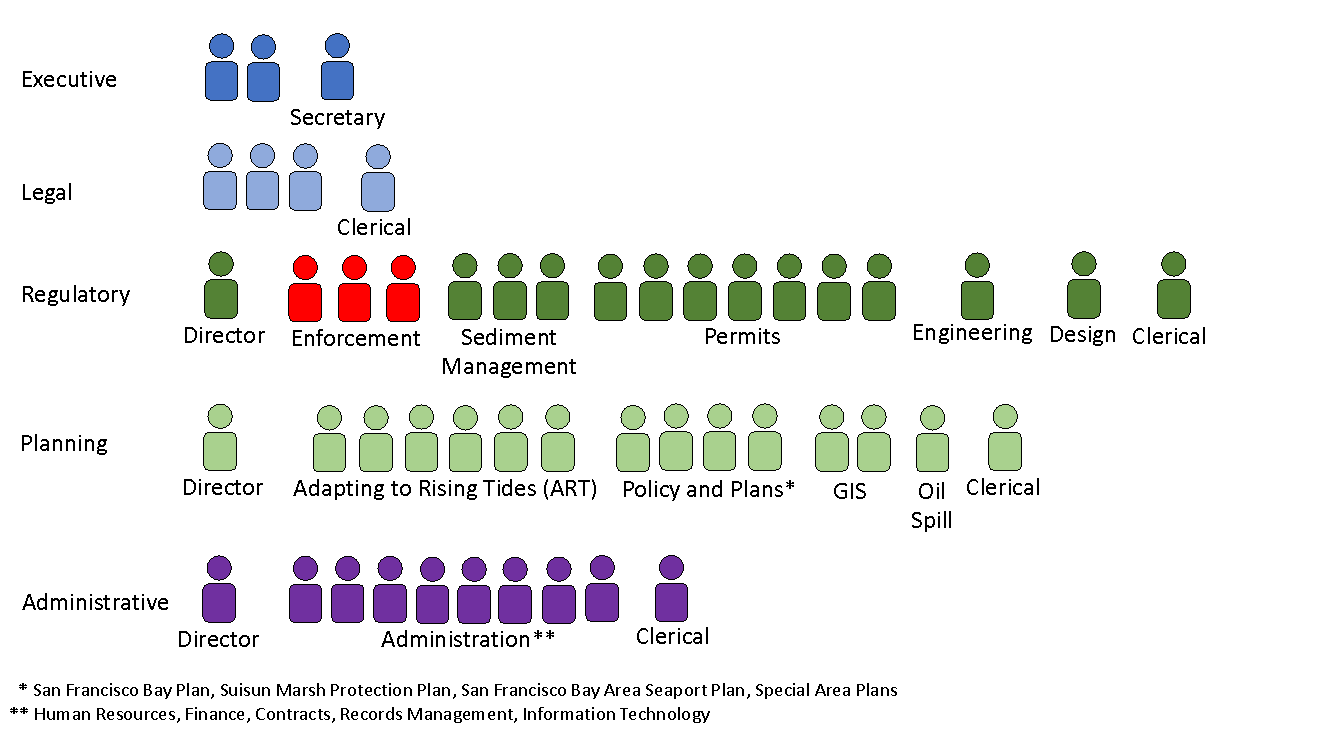

- Conduct a workforce study of all its permit and regulatory activities and determine whether BCDC requires additional staff, including supervisors, to support its mission. BCDC agrees with this recommendation. However, BCDC cannot do so without increased funding, and it is clear now that implementing this report's recommendations will require additions to staff. BCDC needs at least three analysts and additional legal support to undertake the level of enforcement necessary to eliminate the backlog and keep up with the ongoing caseload. In addition to this, staff enhancements for permitting and planning are also known to be necessary, given the current and necessary work associated with a changing climate and rising sea level. With over 7.5 million residents in the Bay Area, San Francisco Bay is the most urbanized estuary in California. As depicted in the attached graphic, BCDC is currently comprised of a total of 49 people who accomplish myriad functions, including Regulatory, Planning, and Administrative duties for the San Francisco Bay and the Suisun Marsh. Each of the three divisions are comprised of several small teams. Although the BCDC staff work collaboratively across teams to increase efficiencies, making one small team larger by making another small team smaller would severely compromise the agency's overall effectiveness.

- Implement a permit compliance position to support the efforts of enforcement staff and the implementation of process changes. If necessary, the commission should seek additional funding for such a position. BCDC agrees with this recommendation and BCDC will also request additional funding to acquire new tools to further compliance efforts.

- Update its existing database or create a new database to ensure that it can identify and track individual violations within each case, including the date staff initiate the standardized fines process for each violation. As part of this process, the commission should review its database and update it as necessary to ensure that it includes all necessary and accurate information, specifically whether staff initiated the standardized fines process for open case files and for those case files closed within the past five years. BCDC agrees with this recommendation to improve the database, although it also believes that a new and more encompassing holistic regulatory tool is required to implement the recommendations in the draft report. As discussed with the audit team and explained above, BCDC requires additional records management tools to track cases. BCDC has been engaged in an ongoing effort to improve its data management, but recognizes that this effort is limited by a lack of resources to obtain the technological tools that it needs to make critical improvements.

- Create and implement regulations that identify required milestones and timeframes for enforcement. BCDC agrees with the recommendation to establish milestones and timeframes for enforcement cases, but does not agree that regulations are necessary to accomplish this. In pursuing this goal, BCDC intends to ensure that the milestones and timeframes can be appropriately tailored to the action to ensure that each action can be resolved efficiently and in the manner most appropriate to the violation.

- Create and implement regulations that define substantial harm, provide explicit criteria for calculating the number of violations present in individual enforcement cases, and specify a process to handle any necessary exceptions to the criteria. BCDC agrees with the recommendation to develop explicit criteria for calculating the number of violations depending on the nature and the circumstances presented by enforcement cases, but does not agree that regulations are needed for this purpose. Staff will explore means of defining substantial harm, taking into account the types of violations and site-specific considerations that may be presented in a range of circumstances, but does not agree that this is necessarily best done through a regulation.

- Create and implement regulations to allow BCDC to use limited monetary fines to resolve selected minor violations that do not involve substantial harm to the Bay. The existing standardized fine regulations are intended to address and resolve minor violations. BCDC will evaluate amendments or additional regulations that may facilitate the resolution of minor violations.

- Update its regulations on permit issuance to offer greater clarity on the types of projects for which staff may issue permits without commissioners' hearings. Existing regulations specify the types of projects for which staff may issue administrative permits or permit amendments without Commission hearings. BCDC agrees that an update to the regulations to provide greater clarity on permitting may be beneficial and will explore means of providing greater clarity on such permitting issues and ensuring that the Commission has sufficient oversight of the issuance of minor permits.

PART III - IDENTIFIED ISSUES AND CORRECTIONS

Title. The subtitle does not have any connection to the text of the document or the findings of the audit committee. This is an attention-grabbling phrase, but to adequately represent the content of the report, the subtitle should be changed to “It's Failure to Prioritize Enforcement and Compliance Has Jeopardized the San Francisco Bay.”

Page 5. We understand the audit staff's concerns with amnesty in the manner in which it is discussed in this section of the report, but it is important to note that there were many different concepts explored during the Commission's discussion of amnesty, along with many other alternatives, and this section of the report presents only a few of them.

The report incorrectly states that Commission regulations require that enforcement cases “representing significant harm to the Bay go directly to the commissioners for enforcement.” In fact, at the discretion of the Executive Director, cases warranting the commencement of a commission enforcement proceeding include, but are not limited to, cases where the alleged violation has resulted in significant harm to the Bay's resources. The text implies that only cases for which staff has determined that there is significant harm to the Bay are presented to the Commission, and this is not the case. Rather, significant harm is a consideration that can make a violation ineligible for resolution through the standardized fine regulations. There should be a recognition that Section 11321 of BCDC's regulations governs decisions to commence Commission enforcement proceedings, and there are various considerations that are weighed prior to the issuance of a violation report, with the primary consideration being the best means of resolving the violation.

The draft report also fails to identify the “beached ship” that was allowed to decay in the Bay, but, assuming that it is the tugboat discussed on Page 28, please see the discussion below. This is not an example that shows improper delegation or insufficient Commission oversight. It is an example of the complexity of many of the violations that arise within BCDC's jurisdiction, and there are multiple state and local agencies that have been working to resolve the issue with this tugboat and other tugboats on state trust lands.

Page 7. It would be beneficial to note that the report cites one case that was not prioritized correctly out of hundreds of case files that were examined.

Page 11. The report would be more accurate if it cited the number of permits that were denied by the Commission in addition to the number of permits that were approved. The last sentence could be revised to state, “The commission reported that, from 1970 through 2018, it had approved 630 permits and denied 29 permits for major projects, and approved almost 3,900 administrative permits and denied 11 administrative permits for minor projects.”

The draft report also varies in reporting the number of staff. The correct number of existing staff is 49. Throughout the document, various numbers are used, including 47 staff on page 11, 46 staff on page 30, and 48 staff is used elsewhere in the document.

Page 12. The San Francisco Bay Plan does not specify design requirements, nor does it indicate specifically how developers should provide public access. Instead, the Bay Plan outlines broad policy goals related to appearance and design of shoreline development and public access. Therefore, the sentence in the first paragraph should read: “For example, the Bay Plan specifies that developers should provide public access to the Bay and it directs developers to use BCDC's Public Access Design Guidelines and take advantage of BCDC's Design Review Board when designing those public access areas.”

Page 13. The Commission is not solely responsible for enforcing state law. Responsibility is also shared by the Attorney General and the judiciary.

In addition, in relation to the text in the second paragraph, enforcement staff may also enter into agreements with violators to resolve violations.

Page 14A. State law (the McAteer-Petris Act) does not describe the enforcement process as depicted. The standardized fine process is set forth in BCDC's regulations. Also, under the staff-level flow diagram, fines are assessed based on the number of days after the 35th day, not the 36th day.

Page 15. The report incorrectly states that two recent enforcement cases resulted in litigation against the Commission. Only one recent enforcement case resulted in litigation against the Commission. It is true, as acknowledged in footnote 4, that in December 2017, a Solano County Superior Court judge set aside a Commission cease and desist and civil penalty order against the responsible parties for numerous violations of the McAteer-Petris Act and the Suisun Marsh Preservation Act, and that the case is now on appeal. However, the report fails to note that: (1) the same Solano Superior Court judge also set aside the orders issued by the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board for unpermitted activities at the island, and that case is also on appeal; and (2) the United States Environmental Protection Agency has filed suit against the responsible parties in federal district court in Sacramento for unpermitted dredge and fill activities at the island in violation of Section 404 of the federal Clean Water Act, and that case is scheduled to go to trial in May 2019. Thus, this is not a case reflecting deficiencies in the Commission's enforcement program; every regulatory agency with jurisdiction has found that the responsible parties committed significant violations of applicable environmental laws warranting both remedial action and substantial penalties. The second enforcement case referred to in the report did not result in litigation challenging a commission enforcement order. That case was settled without litigation related to the violation.

Page 15B. Figure 6 does not fully reflect the existing staff allocations at BCDC. Please see Revised Figure 6 attached as Exhibit A to this Letter.

Page 17. The last sentence states that the Commission has used the Bay Fill Clean-up and Abatement Fund to pay for staff salaries. This (and all other similar references) should be corrected to note that it has been used only for enforcement staff salaries.

Pages 18-19. The statement that the Commission has been reluctant to pursue enforcement in Richardson's Bay because it is highly “political” is inaccurate and may have been taken out of context. BCDC does not decline to pursue an enforcement action based on political considerations. In fact, the Enforcement Committee recently held a briefing to receive an update and information on the Richardson's Bay situation from all parties involved and acknowledged the desire for continued engagement on the issue, thus demonstrating its position on this situation and the need for a resolution. BCDC has determined that a comprehensive public policy that involves all stakeholders in the solution, rather than imposing isolated enforcement, would best serve the situation. The text also fails to recognize the extensive process involved in removing even unoccupied boats from the Bay.

Page 21. As noted above, the text should note that the examples are only a few of the many concepts that were explored by the Commission. The draft report also does not mention that staff had presented the negative implication of an amnesty initiative to the Enforcement Committee, including cautioning that adopting some level of amnesty program would not result in a permanent fix to the backlog.

Page 28. The tugboat involved in the case discussed is located on tidelands under the jurisdiction of the State Lands Commission, adding to the complexity of the situation, and this is reflected in the file that audit staff reviewed. There are also additional facts that led to the closure of this case. Although the case file may not reflect it, BCDC was informed that the vessel was cleared of fuel before the case was closed. While there could be disagreement over whether it was appropriate to close the case without any confirmation that this California state agency, which at the time appeared to be engaged in the process of remedying the situation, was able to resolve the violation, it is misleading to omit the fact that the violation involved another state agency, which was taking the lead in the matter. This is a factor in the determination that was made at the time. It should be noted that, while it may not be fully reflected in the file, the case was closed following a request from county law enforcement indicating that they were addressing the matter.

The Commission also disagrees with any implication that it has failed to provide adequate guidance to staff and that it has improperly delegated enforcement duties to staff. The Commission has adopted comprehensive regulations governing enforcement procedures which provided detailed guidance to staff. 14 C.C.R. §§ 11300-11386. Those regulations give the Executive Director substantial discretion to conduct enforcement investigations, commence commission enforcement proceedings, and administer standardized fines for specified violations under specified conditions.

Page 29. The text states that 24 cases were reviewed and the team found “no documentation of supervisor review in 15 cases.” As noted above, there is supervisor review of all communications, with legal review and/or review from management often conducted as well. These reviews are not documented in the case file, because there has not been a reason to retain marked-up, internal drafts. In fact, these are not records retained under the records retention schedule, and instead, the final communication is reflected in the file.

Page 31. The discussion of Suisun Marsh governance should reflect that the Suisun Marsh Preservation Act provides for the Suisun Marsh Protection Plan that was prepared and adopted by BCDC. The local agencies then prepared their respective components of a Suisun Marsh Local Protection Program (not “a local protection plan”) that must be consistent with the Act and the Plan and that were approved by BCDC.

Pages 32-33. The text cites a BCDC staff statement that “the commission has never issued recommendations to local agencies related to the marsh plan.” This quote is taken out of context and is misleading as it implies that BCDC has not made any recommendations to Suisun Marsh local agencies. As we have discussed with audit staff, while the Commission has not adopted formal recommendations pursuant to a comprehensive five-year review, which was the basis of the quote, BCDC has repeatedly made recommendations to local agencies regarding revisions to their Suisun Marsh Local Protection Program components. As noted above, BCDC intends to conduct a comprehensive review of the Marsh. We recommend that the text be revised to state: “the commission has never issued formal recommendations to local agencies related to the Suisun Marsh Local Protection Program.” While we appreciate the recognition that BCDC has assisted local agencies to update components of the Suisun Marsh Local Protection Program, we request that the text also note that as part of these efforts, BCDC also made recommendations to the agencies regarding updating their components.

Page 35. BCDC does not solely rely on the public or other agencies to report potential violations. The text should reflect that enforcement staff receive many reports from other BCDC staff (both permitting and enforcement), including reports through permitting staff while they are conducting site visits at nearby locations.

Page 43. Footnote 8 incorrectly describes the fines for only one of the six categories set forth in the standardized fine regulations – the placement of fill, the extraction of materials or a change in use that could not be authorized under the Commission's regulations. The description in the draft report is incorrect in stating that: (1) if a violation persists for more than 66 days and up to 95 days, violations will accrue an additional fine of up to $8,000, in addition to an initial fine of up to $3,000 for the 35th through 65th day of violation; and (2) if a violation persists for more than 95 days, violations will accrue an additional fine of up to $8,000 and $100 per day for each day until they correct the violation. Contrary to the statements in the report, the fines established for a lengthy duration of time during which a violation persists are not cumulative. Footnote 8 does not attempt to describe the fines established for the other five categories of violations covered by the regulation. The schedules of standardized fines for each of the six categories of violations covered by the regulation are complex. Rather than summarize them in a footnote, we recommend a reference to the Commission regulations in 14 C.C.R. §§ 11386(e)(1)- (e)(6).

Page 47. The effort-scoring aspect of the matrix in 2018 only applies to the cases that have already been determined to be the highest priority cases. The effort score is meant to balance impact and effort to determine where the Bay and its shoreline will get the most benefit for staff's efforts in a limited-resource environment.

Page 50. The draft report states that the audit staff would have expected the commission's database to document the cases in which staff had initiated the standardized fine process and to identify the individual violations in those cases. While BCDC does not have a specific data field to automatically calculate this information, the database is sufficient to determine whether a violator has past violations. This information is easily found by checking the following fields in the database: location (i.e. x/y coordinates), permittee or respondent, permit number, description of the alleged violation, date of resolution, and resolution description.

The draft report also states that “the database indicates that staff sent only two notice letters — which start the standardized fine process—from 2002 through 2018. This conflicts with our review of the commission's paper files, which showed that staff had issued 25 notice letters from 2012 to 2017.” As staff explained previously, this is simply because staff have not had the time and resources to input all information for cases that were entered before this particular aspect of the database (i.e. “Date 35-day letter sent”) existed.

Page 51. The database is highly useful to the enforcement team as a tool to intake and track the enforcement caseload. It is a major improvement compared to mid-2018. That said, BCDC does not dispute that improvements can be made and better tools should be obtained.

Page 52. The report states that audit staff analyzed the budget data provided by the Commission and determined that, had Commission staff performed the fee calculation in 2013, the Commission likely would have increased its fees and collected for the General Fund by an additional $1 million since 2013. While the audit staff discussed certain differences in the data they used, in comparison with the data used by commission staff in evaluating whether the fees should be adjusted in 2017, audit staff did not share their calculations and, therefore, BCDC staff cannot assess the accuracy of those calculations. However, audit staff incorrectly used only four years of permit fee and regulatory program costs data, rather than data for a five-year period as required by the regulations. Moreover, the audit staff used an unrealistic assumption that adjusted fees would become effective promptly on January 1, 2013, whereas if audit staff had used data for a five-year period and allowed time for all the data to be collected and analyzed, any adjusted fees clearly would not have become effective until January 1, 2015, at the earliest. Thus, the report substantially over estimates any additional permit fee revenue the commission might have collected had it evaluated whether to adjust permit fees at the earliest possible time under its regulations.

As the draft report notes, when the Commission staff evaluated whether the fees should be adjusted, staff determined that no increase in fees was necessary based on its calculations using the most recent five years of budget data. The data used by staff and its analysis was presented to the Commission in a transparent public process which included a detailed staff report.

Finally, the draft report states that it was unclear why the evaluation of whether the permit fees would be adjusted was delayed, noting that BCDC stated this was in part because the Commission lack of a chief counsel. The draft report fails to note that the Executive Director also attributed the delay to the commission's lack of a chief budget officer. Without a chief budget officer, there was no staff available with the expertise to retrieve and analyze the budget data needed to perform the calculations called for by the regulations. Moreover, prior to bringing on its chief counsel to manage the legally-required regulatory process, the Commission's one staff counsel was overburdened with the daily tasks of supporting permitting and other critical functions and lacked the capacity to evaluate whether the fees would be adjusted under the regulations.

Page 56 – Conclusions. The first sentence is unjustly broad, and, as discussed above, ignores the tremendous job done by BCDC in implementing a permitting process that has protected the San Francisco Bay and the Suisun Marsh and in leading the region in addressing sea level rise and climate change through planning and permitting processes. There are no findings in the draft report that BCDC has failed in any of its duties, aside from the identified issues with the enforcement program. This sentence should be revised to state “The commission has failed to fully and consistently execute its enforcement function, and, as a result, has allowed potential ongoing harm to the Bay.”

Exhibit A

Comments

CALIFORNIA STATE AUDITOR’S COMMENTS ON THE RESPONSE FROM THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY CONSERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION

To provide clarity and perspective, we are commenting on the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission’s (commission) response to our audit. The numbers below correspond to numbers we have placed in the margin of the commission’s response.

We note here in our report that the commission has not conducted a study to determine the level of staff it needs, and here we recommend that the commission conduct such a study. The results of such a study will help the commission make its case for more resources to the Legislature, as we state here.

One of the objectives for this audit was to look at the extent to which the commission prevents real and perceived conflicts of interest. As we note in Table A under objective 6, we did not identify any significant issues related to the commission’s compliance with filing requirements related to conflict of interest. However, many of the objectives for this audit concerned the commission’s enforcement process. In this area, we concluded beginning here that staff lack guidance regarding how to conduct enforcement and that the commission has not developed a process to ensure management review of staff decisions. Further, beginning here, we conclude that staff do not always follow commission requirements related to imposing fines. This creates an atmosphere where staff may exercise discretion in an inappropriate manner. While our work did not identify specific instances of impropriety, without sufficient guidance and oversight, the risk exists.

The commission is incorrect that we made no findings that the commission failed to comply with open meeting requirements. Here we describe a finding that the commission did not maintain minutes of closed sessions as required by law.

We stand by our conclusion that the commission has neglected its mission to protect the Bay and the Suisun Marsh. Here, here, and here, we acknowledge the commission’s management of the Adapting to Rising Tides program, its work with local agencies to update components of the marsh program, and its permitting efforts. Nevertheless, our findings in total show a neglect of duties. Specifically, the commission’s backlog of enforcement cases has been growing in recent years, as we discuss here. Also, the commission lacks sufficient guidance to ensure staff conduct enforcement activities consistently as we describe beginning here. Further, the commission has not conducted a periodic, comprehensive review of the Suisun Marsh program, as we state here. Moreover, we note that the commission inconsistently applies its regulations beginning here. We describe specific examples of harm to the Bay from the commission not fulfilling its duties here and here.

Enforcement is a key part of the commission’s responsibilities that enables it to protect the Bay. The commission states in its response that “protecting the Bay is integral to everything [the commission] does.” We agree. As such, when the commission does not perform certain enforcement-related duties well or at all, as we describe in our report, it neglects to protect the Bay.

The commission does not state our finding correctly. We acknowledge here that site visits sometimes occur during the course of other work. However, the commission does not proactively conduct such visits, nor does it have policies to do so. We recommend here that the commission develop procedures to require staff to conduct proactive enforcement, such as site visits, as resources allow.

We stand by our finding that the commissioners improperly delegated their authority. As we say here, “the extent to which the commission may delegate its authority depends on the degree to which it has provided clear guidelines to staff regarding how they may apply, administer, or enforce the authority granted.” We discuss here that the commission’s standardized fines process allows staff to use this process only to resolve cases that do not result in significant harm to the Bay. However, the commission’s regulations do not define or provide guidance on how to define “significant harm.” This gives staff broad discretion to determine which cases go to the commission and which do not, and we provide an example of a case commission staff closed that may have constituted significant harm. Later in the report we also note that commission regulations do not provide guidance on what constitutes a single violation, again giving staff broad discretion.

We question the commission’s assertion that it needs fewer enforcement procedures given the issues we identify such as misapplication of regulations, as discussed here, and inconsistent treatment of alleged violators, as discussed beginning here. Specifically, we note here that the commission has not developed formal guidance for staff regarding critical aspects of the enforcement process.

Undocumented procedures are not sufficient to ensure the consistent application of the commission’s laws and regulations. For example, as we note here, staff do not consistently calculate the number of violations a case may have and have no guidance to identify what constitutes a single violation. In addition, in the section of the report beginning here, we state that staff do not always follow regulations related to fines.

The commission misinterprets what we mean by evidence of management review. Here we describe that in our examination of enforcement cases resolved using standardized fines, we expected to find evidence of management signing off on staff decisions. We did not expect or recommend that the commission maintain draft documents or other nonpublic information in its “public facing” case files. Instead, we expected to see that the commission maintained evidence that, prior to finalizing a decision, a manager or supervisor has reviewed and approved that decision. This could be as simple as a tracking sheet with a manager’s signature.

We appreciate the commission’s additional context and acknowledgement of the shortcomings of its new database, but we stand by our conclusion that it was missing critical information. The commission notes that its database became “operational” shortly before we began our audit. The issues we identify here related to the recording of notice letters and the recording of individual violations are shortcomings that, in our judgment, limit the value of an operational database. In fact, to address certain audit objectives, we needed to create our own database of enforcement cases.

While we appreciate that the commission has begun to develop a plan to acquire a more functional database, it is unfortunate that the commission did not share this with us before its response to our report. We stand by our recommendation that the commission ensure either its existing database or a new platform has the ability to track individual violations and whether staff have initiated standardized fines.

We disagree with the commission’s contention that legislative action, as reflected in several of our legislative recommendations, is not necessary to address several of our findings. Given the commission’s statements that it lacks resources and does not believe it needs to make regulatory changes in some cases, we are concerned that the commission will not implement needed reforms to its processes without legislative action.

The commission suggests we are recommending legislatively imposed timelines. Our recommendation is that the Legislature direct the commission to develop timelines for its enforcement activities.

We have updated the report text to reflect that the commissioners approved a comprehensive review of the marsh program in March 2019 after we had spoken to the commission about this issue. We look forward to evidence of the commission’s implementation of our recommendation in its future responses to our audit.

We stand by our assessment that the commission is not authorized to use the abatement fund to support enforcement staff. As we state here, the expenditures from the fund are restricted to the purposes of removing fill, enhancing resources, and performing remedial clean-up or abatement actions. Further, we note that the mechanism for the use of the fund is through transfer of moneys from the fund to other entities for Bay cleanup. Thus, there is not an expectation that the commission will use the fund to pay enforcement staff salaries.

In our judgment, before it obtains the use of additional enforcement tools, the commission should ensure it has a structured, documented, and consistent enforcement program based on our recommendations to the commission.

We appreciate the commission’s commitment to implementing our recommendation; however, the commission’s statement that “staff actions currently comply with state law” is not accurate. For example, here we provide a specific example where staff pursued the standardized fines process in a case where state regulations did not allow staff to do so.

We stand by our conclusion that there is not sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the commission’s prioritization tools have resulted in the commission more effectively closing cases it has identified as high priority. Six of the eight high-priority cases the commission closed since it began using its new tools in 2016 were in the process of reaching resolution several months before being prioritized by the new tools. We further note that the tools may not designate cases as high priority when they should.

Our dates are consistent. We recommend that the Legislature direct the commission to report on its review of the marsh program by fiscal year 2020–21, and our recommendation to the commission is that it complete one by January 2020, before that fiscal year begins. We discussed timelines for the implementation of our recommendation with the commission on several occasions during the audit but the commission did not inform us that it had determined a specific time frame within which it will be able to accomplish our recommendation. We look forward to its updates on its progress toward addressing our recommendation.

We stand by our recommendation that the commission comply with its statutory duty. State law requires that the commission appoint a citizens’ advisory committee to assist and advise the commission in carrying out its functions, yet the commission insists it will not do so. Further, we disagree with the contention that such a committee is unnecessary and would not benefit the commission’s enforcement efforts. According to state law, the committee should be composed of a variety of experts in conservation, science, architecture, and other areas. As the statutory charge for the advisory committee is to assist the commission “in carrying out its functions,” the commission could use the committee to inform any or all of its efforts, including enforcement.

We recommend that the commission place its milestones and time frames in regulations because such policies are likely to affect parties external to the commission, including alleged violators and permittees. To avoid creating underground regulations, state agencies, with few exceptions, are required to adopt regulations following the process in the Administrative Procedure Act when they issue or enforce any rule of general application to govern their procedures.

We recommend that the commission place its definitions of substantial harm and of what constitutes a violation in regulations because such policies are likely to affect parties external to the commission, including alleged violators and permittees. To avoid creating underground regulations, state agencies, with few exceptions, are required to adopt regulations following the process in the Administrative Procedure Act when they issue or enforce any rule of general application to govern their procedures.

It is unfortunate that the commission did not take the opportunity to communicate to the audit team the concerns it expresses in its response here before submitting its response to the audit report. We reminded the commission on many occasions that it should contact us during its five-day review period if it had any concerns with the draft report. Some of the issues and concerns the commission raises in this section could have been resolved, eliminating the need for the commission to include them in the response.

Our title is accurate and is a reasonable conclusion given the findings described in the audit report.

While preparing our draft report for publication, some page numbers shifted. Therefore, the page numbers the commission cites in its response may not correspond to the page numbers in our final report.

The commission raised concerns over our summary of its amnesty proposals in the Results in Brief section of this report. However, we present a representative selection of its amnesty proposals in detail here. Moreover, we reviewed the transcripts or meeting minutes for each of the commission’s enforcement strategy meetings to identify any additional proposals to reduce the backlog or alternatives to amnesty and found none. Thus, we are puzzled by the commission’s assertion that it discussed many alternatives.

We have updated the sentence here to better reflect regulations. We intended, as we note here, here, and here, to highlight the fact that the commission’s regulations do not allow staff to process cases representing significant harm using the staff-level standardized fines process. Accordingly, staff must process cases representing significant harm using formal enforcement, which with the exception of an executive director-issued cease-and-desist order, would involve commissioners. This report does not assert that staff only present cases containing significant harm to the commissioners.

The tugboat pictured in Figure 8 illustrates our concern about improper delegation. As we discuss here, the commission’s chief of enforcement stated that she closed the case because she thought it was unlikely that the commission would be able to hold the owner accountable. Moreover, the case file contained no evidence that the commission’s executive director, legal counsel, or regulatory director were involved in her decision to close the case. This demonstrates improper delegation because the abandoned tugboat was a violation of state law that had the potential to cause harm to the surrounding area, yet staff appear to have closed the case without sufficient guidance from managers or the commissioners.

For this purpose, we reviewed 29 cases that the commission had prioritized. Here we describe two issues we identified during our review: two cases that seemed incorrectly prioritized relative to each other, and a third case to which staff may have assigned too low of a score.

We focused on the approved permits because they represent the majority of the commission’s permit workload. The commission does not disagree with the permit approval numbers we cited.

The statements in our report concerning the number of commission staff is correct. We report that number as 48, which was provided to us by the commission’s director of administration on March 11, 2019. The other numbers mentioned by the commission appear in our report, but in both cases they are part of discussions in which we do not reference them as the total number of staff.

We agree with the commission that our draft text describing the Bay Plan was unclear. We have modified the text here to read as follows: “Bay Plan policies include design guidelines and information on how developers should provide public access to the Bay.”

We do not assert that the commission has sole responsibility for enforcing state law. As we state here, the commission is responsible for enforcing state law related to its mandate. Further, we note the participation of the Office of the Attorney General in Figure 3.

We corrected the reference in Figure 3 to note that fines accrue after the 35th day. “State law” in the context of the title for Figure 3 refers to both law and regulations; we cite both in the source for the figure.

Our statement that both cases resulted in litigation against the commission is correct. The commission’s response, while offering background information on the first lawsuit, does not refute our statement that the first referenced case resulted in litigation against the commission. Meanwhile, the commission states that the second referenced case did not result in litigation challenging a commission enforcement order. That lawsuit arose out of a California Public Records Act (CPRA) request to the commission for records related to alleged violations or facts asserted in a report on an enforcement action. As part of a larger settlement agreement, the commission agreed to release the plaintiff from allegations set forth in the violation report or any related enforcement activities; in exchange, the plaintiff agreed to dismiss the lawsuit.

Figure 6 provides a high-level overview of the commission staff as of March 2019 and includes several of staff’s primary functions. The additional specificity the commission provided in its Exhibit A is not necessary for this purpose.

While we agree that the commission has spent the abatement fund primarily on enforcement staff salaries, this specificity is irrelevant for the purposes of providing an overview of the commission’s budget practices. We discuss the commission’s specific use of the abatement fund to support the enforcement program here.

The statement that the case is “political” is a quote from the chief of enforcement. The commission did not raise its concern with us when we shared this text at our exit conference. Here we discuss the enforcement committee briefing mentioned in the commission’s response to our report. We are concerned with the commission’s statement that this briefing demonstrated its position on the situation and the need for resolution. Although the executive director shared with us a desire to work on a collaborative policy solution during this audit, the commission has not taken a formal position. Instead, its enforcement committee simply requested additional briefings on the matter, suggesting that it will continue to monitor and play a passive role in the resolution of this issue. Further, state law gives the commission broad discretion in prescribing corrective action to violations of its law. Thus, we did not believe an explanation of the Richardson agency’s process for vessel removal was relevant or necessary.

We explain here that staff presented these options with the goal of eliminating cases in the commission’s backlog. This report does not assert that the commission or its staff believe amnesty will permanently fix the backlog. Rather, as we note here, here, and here, without a strategy to resolve the causes of the backlog, the commission risks allowing it to reoccur.

The tugboat is in the commission’s jurisdiction. We would expect that collaboration with another state agency would assist the commission in reaching resolution, not absolve the commission of its responsibility to address a violation of state law within its jurisdiction. In fact, correspondence in the enforcement case file demonstrates staff knew that the State Lands Commission’s attempt to remove the boat had failed. Thus, we focus on the commission’s role in the case. Moreover, the case file does not indicate that another agency agreed to take the lead on the case, that a request from law enforcement contributed to case closure, or that anyone had cleared the abandoned vessel of fuel. Further, when we discussed our concerns with the staff member responsible for closing the case, she did not provide any of this additional information.

As a regulatory agency, we would expect the commission to take reasonable steps to ensure that its constituents receive consistent treatment. The case files we discuss here represent all cases within the audit period in which commission staff initiated the standardized fines process and closed the case at the staff level. Given that the standardized fines process subjects alleged violators to monetary penalties, we strongly disagree with the commission’s assertion that there is no reason to retain evidence of review. In addition, as we note in Appendix A, we interviewed key enforcement staff and managers to identify relevant policies and procedures. None of the interviewees mentioned a document retention schedule that would prevent the storage of drafts. In fact, here we provide an example of a document that contained mark-ups demonstrating instruction to revise and reissue a notice letter. Further, we cite a discussion with the regulatory director in which he stated that he does not typically review physical case files. Moreover, in Chapter 2 of this report, we provide several instances in which staff failed to follow requirements related to imposing fines. For these reasons, we are not convinced that the commission is conducting systematic review of its enforcement staff’s decisions. As we state in comment 9, undocumented processes are not sufficient to ensure consistency.

We have updated the text beginning here to reflect the commission’s concerns. We agree that our reference to the local protection program as a “plan” may have caused confusion. However, our concern is that the commission has never issued any recommendations for corrective action related to its review of the effective implementation of the marsh program, as defined here. While we appreciate that the commission may have issued recommendations to local agencies related to updating their respective plans, this is not our focus.

The footnote is a summary of the commission’s standardized fines penalties. It very clearly states that the fixed rates depend on the type of violation and the number of days violators take to correct it. Moreover, all amounts are preceded by the words “up to” which indicates that they represent the maximum for each category, not a particular violation type. However, we agree that the fines are not cumulative and have updated our text in the footnote to reflect this.

Commission staff explained to us that they consider cases above a certain impact score as “high priority.” However, we believe that this designation, which refers to cases staff have only assigned an impact score, is confusing given that the effort score is also a part of the whole prioritization tool. For this reason, we updated our text beginning here to clarify that the effort score is a second filter used by commission staff to prioritize cases.

Our testing of the database referenced here did not identify individual violations in each case even with a review of all database fields. Therefore, although the commission asserts that staff can identify past violators, we concluded that staff cannot use the database to identify individual violations, which is necessary to apply standardized fines for repeat violations. Further, we state here that commission staff were aware that the database lacked important information and that they were making efforts to complete the database during the audit. However, until they complete the database, we stand by our criticism of the system’s functionality.

We acknowledge here that staff informed us about their progress in updating the database. However, we stand by our conclusion about the database’s limited functionality.