Introduction

Background

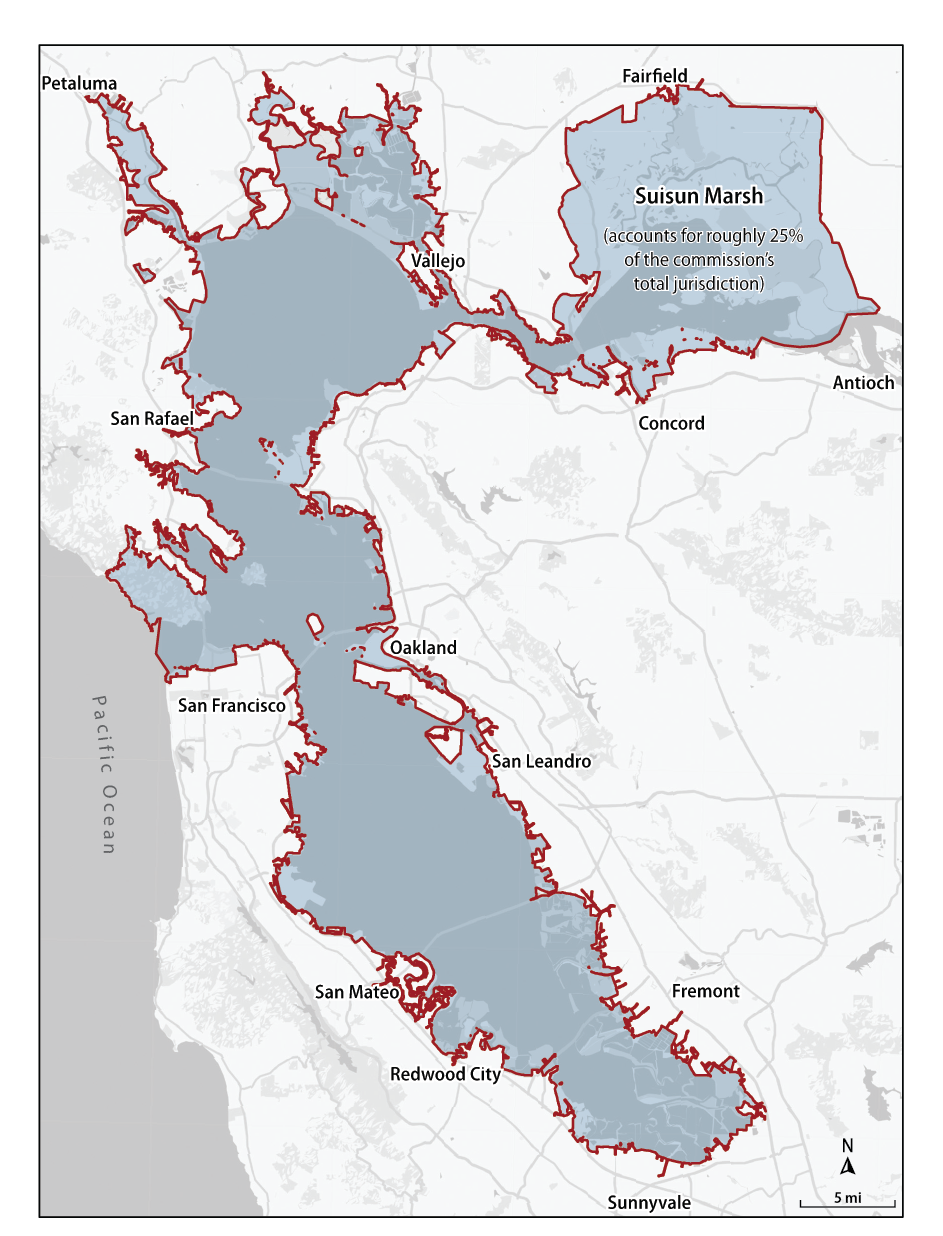

In 1965 the Legislature created the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (commission) to regulate development in and around the San Francisco Bay (Bay). In forming the commission, the Legislature noted the importance of the Bay to the region and stated that future development should minimize the placement of materials in the Bay while ensuring the greatest degree of public access. The commission is responsible for permitting projects within its jurisdiction based on its stated goal of protecting the Bay while encouraging its responsible and productive use. State law establishes the commission’s jurisdiction, which includes the Bay, various waterways, certain salt ponds in the region, and land within 100 feet of the Bay’s shore. State law also designates the commission as the primary state agency responsible for the Suisun Marsh—a unique wetland resource to the northeast of the Bay that serves as a valuable habitat to rare and endangered wildlife and is a critical component of the Pacific Flyway used by migratory birds. Figure 1 illustrates the commission's jurisdiction.

Figure 1

The Commission’s Jurisdiction Includes Both the Bay and Its Shoreline

Source: Commission maps and planning data.

State law sets the commission’s size at 27 members and authorizes the commissioners to appoint an executive director.2 Local governments, state agencies, federal agencies, the Legislature, and the Governor appoint the commissioners, who—as Figure 2 shows—represent different Bay Area interests. In addition, state law allows commissioners to select alternates to serve when the commissioners are not available. As of December 2018, 22 commissioners had appointed alternates. According to several commissioners, the number of commissioners and the composition of the commission are helpful in capturing the wide range of perspectives and interests of the communities around the Bay. The executive director and 47 staff members assist the commissioners in carrying out the responsibilities of the commission.

Figure 2

The 27 Commissioners Represent Varied Bay Area Interests

Source: State law.

Note: The commissioners include representatives from the nine Bay Area counties: Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, Napa, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Solano, and Sonoma. The commissioners also include representatives from the Association of Bay Area Governments, the California State Lands Commission, the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board, the California Department of Transportation, the Department of Finance, the California Natural Resources Agency, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, as well as appointees from the Speaker of the Assembly, the Senate Rules Committee, and the Governor.

The Commission's Responsibilities

One of the commission’s primary responsibilities is to issue or deny permits for projects that involve placing materials in or removing materials from the Bay or otherwise changing the use of land or buildings within its jurisdiction. State law authorizes the commission to approve projects—which may range from residential and commercial endeavors to piers and ports—throughout the Bay and its shoreline. Although staff administratively process permit applications related to minor repairs or improvements, the commissioners regularly hold formal hearings to approve or reject permits for major developments in and around the Bay. The commission reported that it approved 630 permits for major projects and almost 3,900 administrative permits for minor projects from 1970 through 2018 .

Selected Projects Under the ART Program

Using a collaborative approach, the commission leads and supports projects to understand risks from sea‑level rise.

- Local

- - Assessed Alameda County’s vulnerability and risk concerning sea‑level rise and storm events.

- - Conducted a climate adaptation effort to address sea‑level rise in Contra Costa County.

- Regional

- - Developed Bay Area sea‑level rise and shoreline analysis maps.

- - Identified housing and communities vulnerable to flooding in the Bay Area.

- Sector

- - Evaluated sea‑level rise and storm event flooding vulnerabilities facing the Bay Area’s transportation infrastructure.

- - Studied nature‑based solutions for improving shoreline resilience.

Source: ART program’s website and the commission’s website.

The commission also engages in long-term planning activities. State law empowers the commission to amend and enforce the San Francisco Bay Plan (Bay Plan) it created, which details policies for the development and preservation of the Bay and surrounding areas. For example, the Bay Plan policies include design guidelines and information on how developers should provide public access to the Bay. In addition, the commission manages the Adapting to Rising Tides program (ART), which identifies how current and future flooding may affect communities, infrastructure, ecosystems, and the economy. ART works to address sea-level rise through a collaborative process involving multiple agencies. According to the commission, ART consists of different local, regional, and sector-specific projects, as the text box describes.3 In addition to managing ART, staff indicated that the commission seeks to address sea-level rise through its regulatory process by, for example, ensuring that public access is located, designed, and managed to avoid flood impacts, or requiring permit holders in the Suisun Marsh to monitor flooding vulnerability.

The commission also administers the Bay Fill Clean-Up and Abatement Fund (abatement fund), which the Legislature established to pay for clean-up projects in the Bay. State law specifically requires that the abatement fund be available for fill removal, resource enhancement, and any other remedial clean-up or abatement actions. The abatement fund receives its revenue from regulatory penalties that the commission levies against entities that violate state law or commission permits. In June 2018, the abatement fund totaled more than $1.4 million, having received over $280,000 in fine revenue during the previous fiscal year.

The Commission's Enforcement Duties and Procedures

The commission is responsible for enforcing state law related to its mandate and permits it grants within its jurisdiction. To this end, the commission has adopted regulations that allow staff to resolve many violations through a standardized fines process. The commission’s enforcement unit consists of three staff members who investigate allegations related to unauthorized Bay fill or construction, obstruction or misuse of public access amenities, and other permit or statutory violations. To resolve certain violations, enforcement staff may issue new permits or amend existing permits.

Staff may also fine violators who do not correct violations within a grace period, with the amount of the fine increasing over time until the violator corrects the problem or the fine reaches the $30,000 maximum for individual violations.4 Because a single enforcement case often contains multiple violations, a violator may accrue fines well beyond the $30,000 individual maximum. A violator may appeal a staff-level fine by requesting a hearing with the commissioners or by submitting a request for fine reduction to the executive director and commission chair. Staff do not collect fines until violators have corrected the violations, and if a violator refuses to take corrective action, staff may refer the case to the commissioners for a hearing or for the commissioners to consider forwarding the case directly to the Office of the Attorney General for litigation.

As Figure 3 shows, state regulations do not allow enforcement staff to process at the staff level violations that have caused significant harm to the Bay; instead, these cases may be presented to the commissioners at a formal enforcement hearing. Staff generally present formal enforcement cases to the enforcement committee, which consists of up to six commissioners and alternates. Before the enforcement committee hearing, staff prepare a violation report summarizing the case history and violations and recommending a course of action. The enforcement committee reviews the violation report and supporting documentation, holds hearings, and recommends a decision to the commissioners for a vote. The enforcement committee’s recommendations may include civil penalties that, like standardized fines, have a maximum of $30,000 per violation. The enforcement committee may also recommend that the commissioners issue a cease-and-desist order to stop the activity causing the violation.

Figure 3

State Law Describes the Commission's Enforcement Process

Source: State law and commission regulations.

* If the violator disagrees with the staff-imposed fine, the violator may appeal it to the executive director and commission chair. Further, the violator may request a formal enforcement hearing if the violator believes it is necessary to determine the appropriate penalty amounts.

† If the violator refuses to pay a standardized fine, the executive director may begin formal enforcement. If the violator refuses to pay a penalty approved by the commissioners, they may refer the case to the Office of the Attorney General.

† The executive director may also issue a temporary cease-and-desist order, or the commission may refer the case to the Office of the Attorney General.

When voting on an enforcement committee recommendation, the commissioners may take a number of different actions, including approving the recommendation, sending the issue back to the enforcement committee, or dismissing the entire case. Figure 4 shows the roles of the staff, enforcement committee, and commissioners in this process. Violators cannot appeal the commissioners’ decisions, other than through litigation. The Office of the Attorney General litigates cases as necessary to collect penalties after the commissioners make a decision.

Figure 4

The Commissioners and Staff Have Roles in the Permitting and Enforcement Process

Source: The commission, state law, and commission regulations.

From 2016 through 2017, staff forwarded seven formal enforcement cases to the commissioners, who ultimately assessed penalties or approved settlements of more than $100,000 in five of them. Because some of these cases involved prominent businesses in the Bay Area, public attention concerning the commission’s actions and its enforcement program has increased. For example, a case involving the use and modification of a public pavilion at a restaurant in Oakland resulted in a penalty of over $300,000. Alleged violators and outside groups have accused the commission of maintaining unreasonable standards and seeking to levy the largest fines possible. Two of the recent formal enforcement cases resulted in litigation against the commission.5

The Commission's Budget and Staffing

In fiscal year 2017–18, the commission’s budget was $6.95 million, $5.11 million of which funded staff compensation. As Figure 5 shows, since fiscal year 2014–15, most of the commission’s compensation expenses are for permitting, administrative, and planning staff, which includes the commission’s executives, human resources staff, and ART program staff. The commission spent only a small amount of its budget—less than $500,000—on enforcement staff. Figure 6 details the composition of the commission’s staff and demonstrates the small number of staff dedicated to enforcement. The commission used the portion of its budget that did not relate to compensation to fund its operational and overhead costs, such as rent.

Figure 5

Since 2014 the Commission Has Allocated Limited Resources to Enforcement Staff

Source: Data from the Department of Finance and the commission.

* Administrative and planning staff include the executive, legal, regulatory administration, sediment management, technical services, planning, and administration units.

Figure 6

The Commission Employs 48 Staff Members

Source: Commission staff data as of March 2019.

About 80 percent of the commission’s budget in fiscal year 2017–18 came from the State’s General Fund. The remainder came from the abatement fund; the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund; and reimbursements, which include grants. For example, the commission received a grant of $121,000 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Revenue from the commission’s permit fees goes to the General Fund, while the fines that it collects from violators go to the abatement fund.

Footnotes

2 To ensure clarity throughout this report, we use the word commission to refer to the agency as a whole—both the governing body and staff. We use commissioners to refer to the appointed, governing body. We use staff to refer to the employees who perform the commission's administrative work. Go back to text

3 Sector-level projects range from transportation assessments to developing strategies for protecting the shoreline from rising sea levels, and include projects such as those related to the Capitol Corridor passenger rail line and the East Bay Regional Park District. Go back to text

4 The commission’s standardized fines regulations establish fixed rates depending on the type of violation and the number of days the violator takes to correct it. Violations persisting for more than 35 days and up to 65 days are subject to a fine of up to $3,000. If they persist for more than 65 days and up to 95 days, violators are subject to a fine of up to $8,000. If they persist for more than 95 days, violators are subject to a fine of up to $8,000, plus $100 for each subsequent day until they correct the violation or the fines reach the $30,000 maximum per violation. Go back to text

5 In December 2017, the Solano County Superior Court set aside a $772,000 penalty that the commissioners levied against a Suisun Marsh development. The case is now being appealed. In December 2018, the commission settled a lawsuit with a marina by agreeing to settle its claims against the marina for $150,000. Go back to text