Introduction

Background

Three Security Objectives for Information and Information Systems

Confidentiality: Preserving authorized restrictions to protect personal privacy and proprietary information.

Integrity: Guarding against improper modification or destruction.

Availability: Ensuring timely and reliable access.

Source: Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014.

Cyber attacks on information systems are becoming larger, more frequent, and more sophisticated. In recent years, retailers, financial institutions, and government agencies have all fallen victim to hackers. Because of the interconnected nature of the Internet, no one is isolated from cyber threats. To make matters worse, cyber threats seem to be evolving faster than the defenses that counter them. These trends highlight the importance of information security for California. Information security refers to the protection of information, information systems, equipment, software, and people from a wide spectrum of threats and risks. Implementing appropriate security measures and controls is critical to ensuring the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of both the information and the information systems state entities need to accomplish their missions, fulfill their legal responsibilities, and maintain their day-to-day operations. Information security is also the means by which state entities can protect the privacy of the personal information they hold. The text box describes the three security objectives for safeguarding information and information systems.

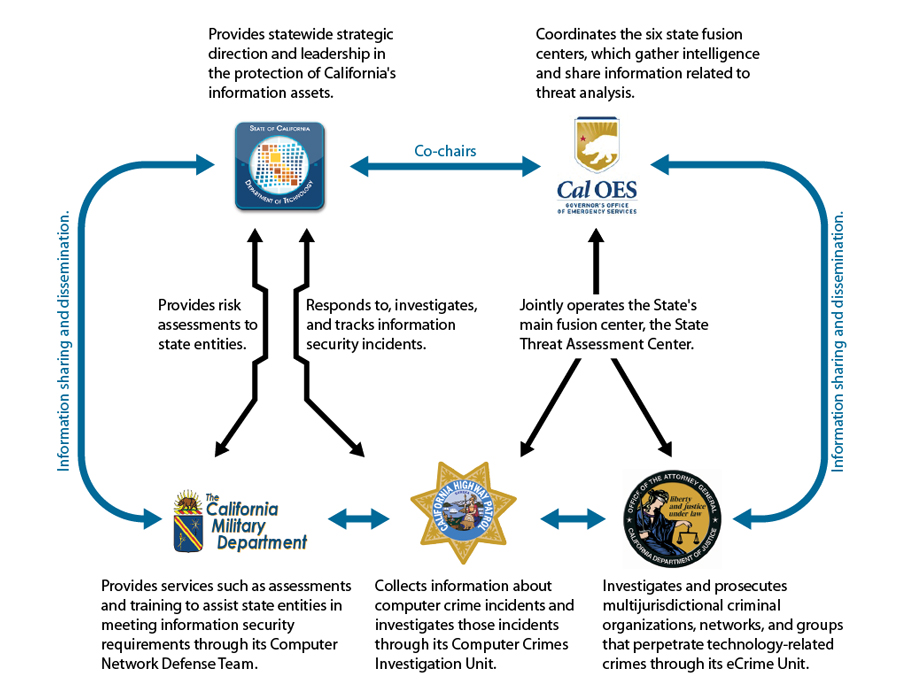

California is a prime target for information security attacks because of the value of its information and the size of its economy—it was ranked the world’s eighth-largest economy in 2013. In fact, according to the director of the California Department of Technology (technology department), California’s data centers that support state agencies’ information technology needs are subject to thousands of hacking attempts every month. Given the State’s increased use of information technology, it has a compelling need to ensure that it protects its information assets, including its information technology equipment, automated information, and software. Accordingly, in 2013, the governor directed his Office of Emergency Services and the technology department to establish the California Cybersecurity Task Force (Task Force). The Task Force’s mission is to enhance the security of California’s digital infrastructure and to create a culture of cybersecurity through collaboration, information sharing, education, and awareness. It is composed of key stakeholders, subject matter experts, and cybersecurity professionals from a variety of backgrounds, including federal and state government, private industry, academia, and law enforcement. As shown in Figure 1, several state entities with different roles and expertise participate in the Task Force.

Figure 1

Key State Entities Related to Information Security That Are Members of the California Cybersecurity Task Force

Various Types of Sensitive Information That State Entities Maintain

Personal information: Social Security numbers, names, and home addresses.

Health information: Medical and dental records, including information protected by laws such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Financial data: Income tax records and bank account information.

Public safety data: Infrastructure, defense, and law enforcement information.

Natural resources information: Locations of water, oil, mineral, and other natural resources.

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of survey responses and review of the state entities’ websites.

In addition to the Task Force, the Legislature recently created the Select Committee on Cybersecurity (committee) for the purpose of examining information security vulnerabilities, assessing resources, educating leaders, and developing partnerships to manage and respond to threats. The committee includes select members of the California State Assembly. By the end of 2015, the committee will produce a report that informs state agencies, private businesses, and relevant institutions about the State’s cybersecurity issues. The report will include a description of entity roles and capacities, policy recommendations, and input from third-party experts.

The State’s Information Assets Are Vital Resources That Contain Various Types of Sensitive Data

The State’s information assets are an essential public resource. In fact, many state entities’ program operations would effectively cease in the absence of key information systems. In some cases, the failure or disruption of information systems would jeopardize public health and safety. Further, if certain types of the State’s information assets became unavailable, it could affect the State’s economy and the citizens who rely on state programs. Finally, the unauthorized modification, deletion, or disclosure of information included in the State’s files and databases could compromise the integrity of state programs and violate individuals’ right to privacy.

As the administrators of a wide variety of state programs and the employers of over 220,000 people, California’s state entities maintain a wide variety of sensitive—and oftentimes confidential—information, as shown in the text box. For example, state entities collect and maintain personal information such as Social Security numbers, birthdates, and fingerprints, as well as legally protected health information. Other state entities collect and store data related to income and corporation tax filings, as well as information related to public safety communications and geographical data, which are used for emergency preparedness and response to disasters.

Data Breaches Are On the Rise

Data breaches are becoming more common for private and public organizations. In 2014 the Ponemon Institute (Ponemon)—which conducts independent research on privacy, data protection, and information security policy—conducted a survey of over 560 executives in the United States regarding information security and found that data breaches of companies have increased in frequency.1 Specifically, 43 percent of the respondents in Ponemon’s 2014 survey indicated that their companies had a data breach in the past two years. This represents an increase of 10 percent from Ponemon’s 2013 survey. In addition, of the respondents experiencing a data breach, 60 percent had more than one data breach. This is an increase from the 52 percent in Ponemon’s 2013 survey.

Recent information security breaches have underscored the significant threat facing organizations that use, store, or access sensitive data. For example, Target Corporation (Target), one of the nation’s leading retailers, learned in December 2013 that hackers had infiltrated its computer system and stolen up to 70 million customers’ personal data and credit card information. In February 2015 Target disclosed that the costs of the breach had reached $252 million. In September 2014 The Home Depot, a large home improvement retailer, reported that a breach between April 2014 and September 2014 put information related to 56 million payment cards at risk. The Home Depot estimated that the cost of the breach would reach approximately $62 million in 2014. The following month, JP Morgan Chase, the nation’s largest commercial bank in terms of assets, announced a massive data breach that affected approximately 76 million households and 7 million small businesses. More recently, insurance company Anthem Inc. suffered a breach that potentially exposed nearly 80 million customer records—including Social Security numbers.

Government entities were not immune to information system breaches during this same time frame. A breach at Montana’s Department of Public Health and Human Services in May 2014 may have exposed Social Security numbers and other personal information of 1.3 million people. In October 2014 Oregon’s Employment Department identified a security vulnerability in an information system that stores the personal information of job seekers, such as Social Security information; this vulnerability exposed the private information of over 851,000 individuals. Finally, in June 2015 the federal Office of Personnel Management announced a cybersecurity intrusion affecting its information systems that potentially exposed personal information—such as background investigation records, fingerprints, and Social Security numbers—of approximately 20 million current, former, and prospective federal employees and contractors, and their spouses or cohabitants.

Not only can information system breaches of governmental entities impede their ability to meet their missions, but they can also prove costly. According to a Ponemon study, public sector organizations have the highest probability of a data breach involving at least 10,000 records, possibly due to the amount of confidential and sensitive information they collect.2 Moreover, the Ponemon study estimated that the average cost per record lost in the public sector is $172, placing government entities at risk of incurring significant expenses should they fall victim to a breach of sensitive information.

The Technology Department Is the Primary Authority for Promoting California’s Information Security

The technology department serves as the primary state government authority for ensuring the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of state systems and applications for certain executive branch entities. In 2009 the Governor’s information technology reorganization plan consolidated statewide information technology functions under the former Office of the State Chief Information Officer. This effort integrated the Office of the State Chief Information Officer with the Office of Information Security and Privacy Protection and two other state entities. In 2013 the organization was renamed the California Department of Technology. As the State’s primary authority for information security, it represents California to federal, state, and local government entities; higher education; private industry; and others on security-related matters.

The technology department’s California Information Security Office (security office) is responsible for providing statewide strategic direction and leadership in the protection of the State’s information assets. To this end, state law provides the security office with the responsibility and authority to create, issue, and maintain policies, standards, and procedures, some of which the security office has documented in Chapter 5300 of the State Administrative Manual (security standards). The security standards provide the security and privacy policy framework with which state entities under the direct authority of the governor (reporting entities) must comply.3 The security standards consist of 64 different compliance sections. In addition, they identify the National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 800-53 and the Federal Information Processing Standards as the minimum information security control requirements that reporting entities must meet when planning, developing, implementing, and maintaining their information system security controls. The security standards also reference the Statewide Information Management Manual, which contains additional standards and procedures that address more specific requirements or needs that are unique to California.

Information Security Compliance Forms That the California Department of Technology Requires From Reporting Entities

Designation Letter: Reporting entities must use this form to annually designate key information security roles, including their chief information officers.

Risk Management and Privacy Program Compliance Certification: Reporting entities must use this form to annually certify their compliance with all of Chapter 5300 of the State Administrative Manual (security standards).

Technology Recovery Program Certification: Reporting entities must use this form each year to certify their compliance with technology recovery management program requirements.

Information Security Incident Report: Reporting entities must submit this report, which specifies the details of information security incidents, within 10 business days of reporting the incidents to the California Highway Patrol.

The technology department is also responsible for ensuring that reporting entities comply with the policies it has established. Specifically, state law provides the security office with the authority to direct each reporting entity to effectively manage information technology risk, to advise and consult with each reporting entity on security issues, and to ensure that each reporting entity is in compliance with the requirements specified in the security standards. Moreover, state law provides the security office with the authority to conduct independent security assessments or audits of reporting entities or to require assessments or audits to be conducted at the reporting entities’ expense.

As part of its oversight activities, the security office requires reporting entities to submit a number of different documents related to their compliance with the security standards. Specifically, it requires the heads of reporting entities or their designees to self-certify whether the reporting entities have complied with all policy requirements by submitting the Risk Management and Privacy Program Compliance Certification. Further, the security office requires reporting entities to certify whether they have undergone a comprehensive entitywide risk assessment within the past two years that, at a minimum, measured their compliance with the legal and policy requirements in the security standards. Finally, the security office requires noncompliant reporting entities to develop and submit remediation plans that identify the areas in which they are noncompliant and timelines for achieving compliance. The text box summarizes the standardized forms the security office requires reporting entities to submit.

The technology department provides reporting entities with different types of guidance to assist them in their efforts to comply with the security standards. For example, the technology department’s website provides many resources for implementing appropriate information security controls, such as statewide security policies, statewide manuals, templates, toolkits, security alerts, and links to security training videos and best practices. Additionally, in 2014 the security office offered a one-day basic training course for information security officers to provide an overview of their roles and responsibilities, review required information security procedures, and explain the security office’s expectations for their compliance with the security standards.

The State’s Oversight of Information Technology Controls Is a High-Risk Area

The California State Auditor (state auditor) has previously reported on the deficiencies we identified in the general controls state agencies have implemented over their information systems. The pervasiveness of these deficiencies led to our designating the technology department’s oversight of general controls a high-risk issue. Legislation that became effective in January 2005 authorizes us to develop a program for identifying, auditing, and reporting on high-risk state agencies and statewide issues. In September 2013 we published a report titled High Risk: The California State Auditor’s Updated Assessment of High-Risk Issues the State and Select State Agencies Face (Report 2013-601). This report identified the technology department’s oversight as a high-risk issue for two reasons: the limited reviews the technology department performs to assess the general controls that reporting entities have implemented for their information systems and the deficiencies we noted in such controls at two reporting entities we audited. The report noted that we suspected that similar control deficiencies existed at other entities throughout the State.

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (Corrections) was one of the two reporting entities whose weak controls led us to conclude that the technology department’s oversight was a high-risk issue. In our September 2011 report titled Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation: The Benefits of Its Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions Program Are Uncertain (Report 2010-124), we disclosed that the preliminary results of our review indicated that Corrections had weaknesses in its general controls for a large segment of its information systems. In fact, we deemed the final results of our review too sensitive to release publicly; thus, we issued a separate confidential management letter to Corrections detailing the specific weaknesses we identified. Likewise, in March 2012, we reported on the significant weaknesses we identified at the California Employment Development Department (EDD) in our report titled State of California: Internal Control and State and Federal Compliance Audit Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2011 (Report 2011-002). Specifically, we found that EDD’s entitywide information security policy was outdated, that EDD had an insufficient risk management program, and that EDD did not have an incident response plan prior to 2012.

We concluded that unless Corrections and EDD implemented adequate general controls over their information systems, the completeness, accuracy, validity, and confidentiality of their data would continue to be at risk. However, despite the weaknesses we identified in their controls over their information systems, both entities had previously self-certified to the technology department their compliance with the security standards for the period reviewed. This apparent contradiction caused us to question the adequacy of the technology department’s oversight and led us to designate that oversight a high-risk issue.

Scope and Methodology

As previously discussed, state law authorizes the state auditor to establish a high risk audit program and to issue reports with recommendations for improving state agencies or addressing statewide issues it identifies as high risk. State law also authorizes the state auditor to require state agencies it identifies as high risk and those responsible for high-risk issues to report periodically on their implementation of its recommendations. Programs and functions that are high risk include not only those particularly vulnerable to fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement, but also those that face major challenges associated with their economy, efficiency, or effectiveness.

In our September 2013 report, we issued our latest assessment of high-risk issues that the State and selected agencies face. Based on our inclusion of information technology as a high-risk issue, we performed this audit of the technology department’s oversight of the State’s information security. We list the audit objectives we developed and the methods we used to address them in Table 1.

Assessment of Data Reliability

The U.S. Government Accountability Office, whose standards we are statutorily required to follow, requires us to assess the sufficiency and appropriateness of computer-processed information that we use to support our findings, conclusions, or recommendations. In performing this audit, as shown in Table 1, we surveyed 101 entities that certified their levels of compliance with the security standards to the technology department in 2014 to gather information about their compliance with security standards, perspective on the technology department’s guidance and oversight, and challenges and best practices in implementing the security standards. Because we used the survey data only to summarize assertions obtained directly from the survey respondents, we determined that we did not need to assess the reliability of those data.

Table 1

Audit Objectives and the Methods Used to Address Them

| Audit Objective | Method | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Review and evaluate the laws, policies, and procedures significant to the California Department of Technology’s (technology department) oversight of state information security. | We obtained, reviewed, and evaluated laws, policies, and procedures pertaining to the technology department’s oversight of state information security. |

| 2 | Identify the roles and responsibilities of the agencies that oversee state information security policy. | We identified the roles and responsibilities of the technology department, Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, the California Military Department, the California Highway Patrol, and the Office of the Attorney General related to information security. |

| 3 | Review and assess the information security posture of the state entities under the direct authority of the governor (reporting entities). |

|

| 4 | For a selection of reporting entities, perform a general information system control review of compliance with certain information security standards. |

|

| 5 | Review and evaluate the oversight provided by the technology department. |

|

| 6 | Review and assess any other issues that are significant to the technology department’s oversight of state information security. |

|

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of the information and documentation identified in the column titled Method.

Footnotes

1 The results of the Ponemon 2013 survey were published in a report titled Is Your Company Ready for a Big Data Breach? The Second Annual Study on Data Breach Preparedness. Go back to text

2 The title of the Ponemon study was 2014 Cost of Data Breach Study: United States. Go back to text

3 For this report, we count as reporting entities the 114 entities that the technology department included in its Status of Compliance With Security Reporting Activities report dated October 2014 as the basis for our review. These 114 entities include entities required by state law to report to the technology department each year, as well as some entities that voluntarily reported to the technology department in 2014. Go back to text