Use the following links to jump directly to the Chapter you would like to view:

Chapter 1 Chapter 2Chapter 1

Many State Entities Have Poor Controls Over Their Information Systems, Putting Some of the State’s Most Sensitive Information at Risk

Chapter Summary

Few of the state entities that are under the direct authority of the governor (reporting entities) and therefore within the California Department of Technology’s (technology department) purview have fully complied with the State’s mandated information security and privacy policies, standards, and procedures. The reporting entities’ implementation of these required security measures and controls is critical to ensuring their business continuity and protecting their information assets, including their data-processing capabilities, information technology infrastructure, and data. However, when we performed compliance reviews of selected information security requirements at five reporting entities, we found that each had deficiencies. Similarly, our survey of reporting entities showed that 73 of the 77 respondents reported that they had yet to achieve full compliance with the State’s information security requirements.4

The reporting entities that responded to our survey frequently cited two challenges to achieving compliance with the information security requirements: a lack of resources and competing priorities. However, many survey respondents also identified readily available best practices that may help noncompliant reporting entities. These best practices included networking with other reporting entities and attending information security trainings. Until reporting entities achieve full compliance with the information security requirements, outstanding weaknesses in their controls could compromise the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the information systems they use to perform their day-to-day operations.

Very Few of the Reporting Entities Have Fully Complied With Mandated Information Security Standards

As we discuss in the Introduction, the technology department requires reporting entities to meet the information security standards contained in Chapter 5300 of the State Administrative Manual (security standards). However, the majority of reporting entities—including some that maintain sensitive or confidential information—have yet to achieve full compliance with the security standards. We surveyed 101 reporting entities and asked them to designate their compliance status with each of the 64 sections of the security standards. Only four of the 77 respondents reported that they had fully complied with all of the security standards. Further, 22 respondents indicated that they did not expect to reach full compliance with the security standards until 2018 or later, with 13 reporting that they would be out of compliance until at least 2020. The Appendix presents the respondents’ compliance levels, as well as the list of reporting entities that did not respond to our survey.

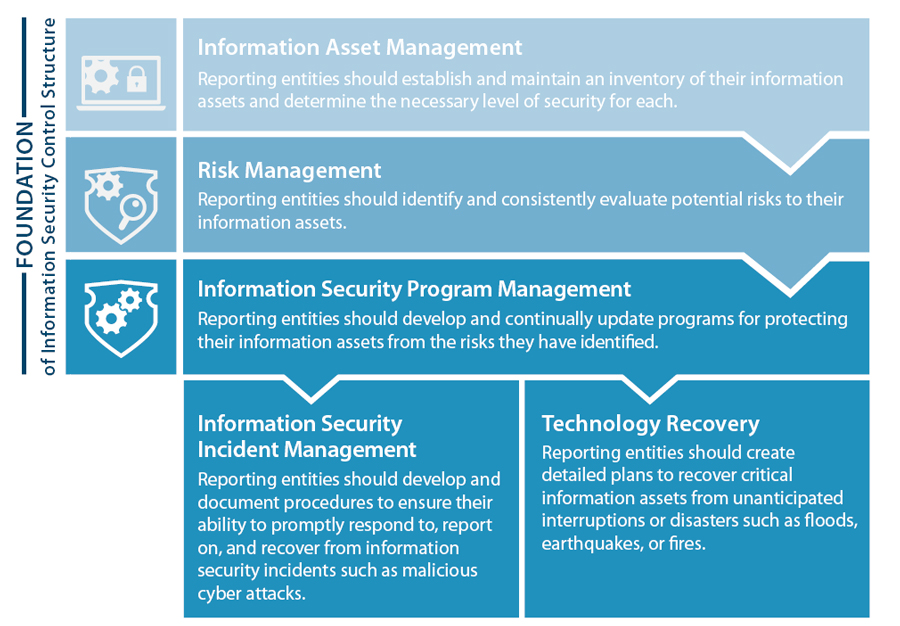

In addition, we performed reviews of key information security documents that we used to substantiate compliance with the security standards at five reporting entities. The reporting entities we reviewed perform a variety of important roles within state government, from regulatory to enforcement activities. We focused our review of security standards on three key control areas that form the foundation of an effective information security control structure: information asset management, risk management, and information security program management. We also reviewed the two control areas related to a reporting entity’s ability to respond to incidents and disasters: information security incident management and technology recovery. Figure 2 describes these five control areas. These control areas relate to 17 of the 64 sections of the security standards.

Figure 2

Five Key Control Areas of Information Security With Which the California Department of Technology Requires Reporting Entities to Comply

Source: California State Auditor’s (state auditor) assessment of the information security standards outlined in Chapter 5300 of the State Administrative Manual (security standards).

Note: The state auditor focused its review on the five key control areas above, which include 17 of the 64 sections of the security standards.

Although all five reporting entities maintain different types of sensitive data, each had deficiencies in their ability to protect such data, as Table 2 shows. In fact, only one achieved full compliance in any of the areas we tested. All five reporting entities have not met or have only partially met the requirements to establish and maintain an inventory of their information assets. Four have not met or have only partially met the requirements associated with two control areas: managing the risks to their information assets and developing a comprehensive information security program to address their risks. In addition, none had fully met the requirements related to developing an incident response plan for handling information security incidents such as malicious cyber attacks and developing a technology recovery plan for addressing unplanned disruptions due to natural disasters or other causes. However, two reporting entities were mostly compliant in these two control areas.

Table 2

Five Reporting Entities’ Levels of Compliance With Select Information Security Control Areas

| Collects, Stores, or Maintains | Reporting Entity | Entity Description |

Personal Information or Health Information Protected by Law |

Confidential Financial Data | Other Sensitive Data | Information Asset Management | Risk Management | Information Security Program Management | Information Security Incident Management | Technology Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Provides critical state services |

Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| B | Administers federal and state programs | Yes | No | No | |||||

| C | Oversees an entitlement program | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| D | Performs enforcement activities | Yes | No | Yes | |||||

| E | Manages critical state resources |

Yes | No | Yes |

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of information security documents, websites, and other information provided by the reporting entities.

Green = Fully compliant: The reporting entity is fully compliant with all the requirements in Chapter 5300 of the State Administrative Manual (security standards) we tested for the control area.

Yellow = Mostly compliant: The reporting entity has attained nearly full compliance with all of the security standards we tested for the control area.

Orange = Partially compliant: The reporting entity has made measurable progress in complying, but has not addressed all of the security standards we tested for the control area.

Red = Not compliant: The reporting entity has not yet addressed the security standards we tested for the control area.

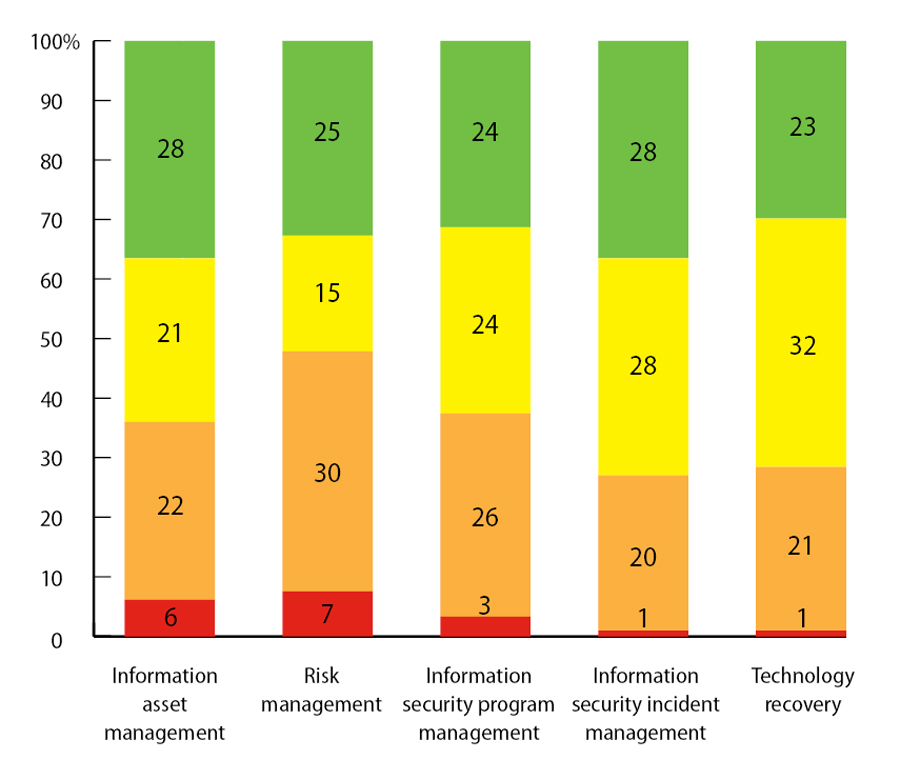

Similarly, as Figure 3 shows, for each of the five control areas, at least 49 of the 77 survey respondents stated that they had yet to achieve full compliance with the security standards. The survey respondents reported that they had made the most progress toward achieving compliance with the information security incident management and technology recovery requirements: More than 70 percent of respondents indicated that they were mostly or fully compliant with these requirements. Conversely, nearly half of the survey respondents indicated that they had not or had only partially met the requirements for risk management. Because our survey includes self-reported information and our control reviews focused only on select information security controls, the reporting entities’ information security controls may have additional deficiencies that we did not identify. Alternatively, some reporting entities may have compensating information security controls that help mitigate some of the risks associated with not being fully compliant. Nevertheless, the weaknesses we identified could compromise the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the information systems these reporting entities currently use to perform their day-to-day operations.

Figure 3

Reporting Entities’ Levels of Compliance With Select Information Security Control Areas, According to Their Survey Responses

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of survey responses from 77 reporting entities.

Green = Fully compliant: The reporting entity is fully compliant with all the requirements in Chapter 5300 of the State Administrative Manual (security standards) for the control area.

Yellow = Mostly compliant: The reporting entity has attained nearly full compliance with all of the security standards for the control area.

Orange = Partially compliant: The reporting entity has made measurable progress in complying, but has not addressed all of the security standards for the control area.

Red = Not compliant: The reporting entity has not yet addressed the security standards for the control area.

Few Reporting Entities Have Established Sufficient Practices for Managing Their Information Assets

To determine the level of protection necessary for their information assets, reporting entities must first identify those assets and assess their importance to their business missions. However, many reporting entities have not developed comprehensive inventories of their information assets that consistently address each of the elements the security standards require. For example, the security standards require each reporting entity to establish and maintain an inventory that identifies the owners, custodians, and users of all its information assets. Further, the inventory must include the importance of each information asset to the reporting entity’s mission and programs. The security standards also require reporting entities to categorize the required level of protection necessary for each information asset based on the potential impact of the loss of the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of that asset. However, 28 of the 77 survey respondents stated that they had not complied or had only partially complied with the security standards for inventorying information assets.

The reporting entities’ failure to fully comply with these security standards may put their information assets at risk. For example, security standards require reporting entities to identify an owner for each information asset, who is responsible for authorizing access based on users’ needs. If an entity does not clearly assign an owner to an information asset, it incurs the risk that personnel who are not in the best position to determine users’ access needs will unknowingly authorize overly broad access to staff. Allowing access by too many users defeats the purpose of access controls and can unnecessarily provide opportunities for fraud, sabotage, and inappropriate disclosures, depending on the sensitivity of the resources involved. For instance, an employee may alter payee information within an information system and direct a payment to himself or herself.

Our reviews raised further concerns about the reporting entities’ management of their information assets. Specifically, we found that none of the five reporting entities we visited had fully complied with the security standards requiring them to establish and maintain an inventory of their information assets. For example, Entity D did not have an inventory of all of its information assets.5 Rather, it asserted that it has a small number of systems and databases, which it informally tracks. Similarly, Entity C did not include in its inventory all information assets from two of its satellite locations.

In addition, Entity C did not identify required information in its inventory, such as a custodian and user for each information asset, nor did it include the potential consequences should the integrity or availability of the information assets be compromised. According to Entity C, its satellite locations previously maintained their own inventories, which caused inconsistencies in the way it inventoried information assets.

To implement an effective information security program, reporting entities need to maintain a complete, accurate, and up-to-date inventory of their information assets. A current inventory is necessary for effective monitoring, testing, and evaluation of information security controls. It is also critical to support information technology planning, budgeting, acquisition, and management. Until reporting entities fully inventory their information assets, they cannot ensure that they have implemented appropriate information system security controls.

Many Reporting Entities Have Failed to Identify Their Information Security Risks

The security standards require not only that reporting entities develop comprehensive inventories of their information assets but also that they use these inventories to perform meaningful risk assessments to identify and manage potential threats. Security standards require each reporting entity to develop a risk management and privacy program that identifies and prioritizes critical information technology applications, among other tasks. Further, each reporting entity must conduct a comprehensive risk assessment once every two years to identify security issues such as threats to their information assets and points where those assets are vulnerable. The risk assessment should consider the range of risks to which an entity’s information systems and data may be subject, including those posed by both authorized users and unauthorized outsiders. The risk assessment process must also identify and estimate the cost of protective measures that would eliminate vulnerabilities or reduce them to acceptable levels.

However, nearly half of the reporting entities we surveyed have yet to comply with these security standards. Despite the importance of conducting a comprehensive risk assessment, 37 of the 77 respondents reported that they had not met or had only partially met the security standards for risk management. If an entity does not assess its vulnerabilities, it cannot address them. For example, if an entity has outdated software containing known security weaknesses, that software may allow an individual to gain access to capabilities that would allow him or her to bypass security features. The individual would then be able to read, modify, or destroy programs such as those containing infrastructure or personal information critical to the State.

Further, our reviews of five reporting entities found that four have not met or have only partially met these requirements. For example, not only had Entity A failed to document its risk management program, it had yet to perform a comprehensive risk assessment. Entity A explained that rather than performing an entitywide risk assessment, as the security standards currently require, it has historically performed a risk assessment once every two years that focused on specific high-risk topic areas. Because Entity A did not anticipate fully remediating the outstanding findings from its December 2014 risk assessment until September 2015, it stated that it did not intend to complete its next comprehensive, entitywide risk assessment until April 2016. Entity A stated that it has begun the initial activities for developing its risk management program and that it intends to use the risk management guidance that the security standards reference.

Similarly, Entity E had significant weaknesses in its risk management program. Although it had performed a limited self-assessment of its information security risks, this assessment determined that it had not identified all of its threats and vulnerabilities, had not defined a cost-effective approach to managing the risks it identified, and had not established time frames for implementing its risk management strategies. According to Entity E, it delayed its efforts to perform a comprehensive risk assessment three years ago to redirect the necessary resources to critical business and operational priorities. Entity E asserted that it now plans to hire a contractor by October 2015 to perform a comprehensive risk assessment because its information technology environment has become increasingly complex over the last two years.

In comparison, Entity B was the only reporting entity we visited that was able to demonstrate full compliance with the risk management requirements we tested. For example, within the last two years, Entity B contracted with an independent third-party vendor to perform a comprehensive entitywide information security risk assessment. Further, Entity B conducted its own internal risk assessments for select control areas in this same time frame.

Risk assessment and risk management require ongoing efforts on the part of the entities involved. Although reporting entities must conduct formal, comprehensive risk assessments at least once every two years, they should consider risk whenever they change their operations or use of technology, or when outside influences affect their operations. Until reporting entities identify all of their information assets and the risks related to those assets, they cannot be certain that they have identified and considered all threats and vulnerabilities to their information systems. Further, they cannot ensure that they have addressed the greatest risks and made appropriate decisions regarding which risks to accept and which to mitigate through security controls.

Many Reporting Entities Do Not Appropriately Manage Their Information Security Programs

When reporting entities understand the value of their information assets and the risks that may compromise them, they can establish appropriate policies and procedures to protect those assets. An entitywide information security management program provides the baseline information security controls and is a reflection of senior management’s commitment to addressing security risks. Accordingly, the security standards require each reporting entity to develop, implement, and maintain an entitywide information security program plan. This information security management program should establish a framework for a continuous cycle of activity related to assessing risk, developing and implementing effective security procedures, and monitoring the effectiveness of those procedures. Reporting entities should divide the program’s management among managerial, technical, and program staff, and should document each position’s specific responsibilities. Without a well-designed information security program, a reporting entity may establish inadequate security controls or may inconsistently apply the controls it has in place. Further, staff may misunderstand or improperly implement their responsibilities. Such conditions may cause an entity to focus its limited resources on developing and implementing controls over low-risk resources, leaving its sensitive or critical resources without sufficient protection.

Despite the importance of information security program management, 29 of the 77 survey respondents reported that they had not met or had only partially met the requirements for this control area. Further, the results of our reviews for four of the five reporting entities we reviewed echoed these trends. Specifically, not only did Entity A lack an entitywide information security program, its existing information security policies were outdated. To ensure the effectiveness of its information security program, an entity should maintain the program’s documentation to reflect current conditions. It should periodically review and, if appropriate, update and reissue documentation to reflect alterations in risk due to factors such as changes to its mission or the types of computer resources it uses. Outdated plans and policies reflect a lack of adequate commitment by management and may be ineffective because they do not address current risks. Entity A acknowledged that because it had not revised its information security policies in several years, they may not be fully compliant with the current security standards. Entity A asserted that it is actively drafting new entitywide information security policies, which it hopes to complete by November 2015. Further, it plans to analyze its existing information security policies and revise them as necessary by December 2015, once it fills a vacant position that will be responsible for completing these revisions.

Similarly, Entity D has not implemented an information security program, nor has it even identified the roles and responsibilities necessary for implementing such a program. According to Entity D, competing priorities and its modest staffing levels have prevented it from achieving full compliance with the security standards for information security program management. Further, Entity D stated that it will examine its workload to determine what additional staff it needs to meet its information technology responsibilities and ensure full compliance with the security standards. Finally, Entity D asserted that as a result of our audit, it will immediately begin developing a plan to ensure that it attains full compliance with the security standards by August 2016.

In contrast, Entity B was the only reporting entity included in our reviews that achieved full compliance with the security standards we tested related to information security program management. Specifically, Entity B has identified and assigned roles and responsibilities for its information security program, including identifying the position that is responsible for the creation, maintenance, and enforcement of its information security policies.

Without effective information security program management, reporting entities cannot effectively manage their risk or ensure the proper use and protection of their information assets. Until noncompliant reporting entities complete and implement effective information security programs, they will continue to be at risk of misuse, loss, disruption, or compromise of state information assets.

Some Reporting Entities Have Not Developed the Capability to Respond to Information Security Incidents

Some reporting entities have yet to develop documented procedures to respond to, report on, and recover from information security incidents, such as malicious cyber attacks against their information assets. A security incident is any occurrence that may jeopardize the confidentiality, integrity, or availability either of an information system or of the information it processes, stores, or transmits. Proper information security incident management includes the adoption of a written incident response plan that provides procedures to detect and respond to incidents. In addition, information security incident management includes learning from past incidents by developing and implementing appropriate corrective actions to prevent similar occurrences in the future. Otherwise, violations may continue, causing damage to an entity’s resources indefinitely and potentially resulting in the continued disclosure of confidential or sensitive information.

For this reason, the security standards require reporting entities to develop, disseminate, and maintain incident response plans that provide for the assembly of appropriate staff who can respond to and recover from a variety of incidents. The incident response plan must include procedures for ensuring that entities promptly investigate incidents involving loss, damage, or misuse of information assets, or improper dissemination of information. Further, the plan must also ensure that the entities provide staff with instruction on how to preserve evidence when handling incidents, since one aspect of incident response that can be especially problematic is gathering evidence to pursue legal action. If staff do not receive training on the proper handling and reporting of security incidents, an entity may not be able to pursue legal action against intruders or violators.

Despite the importance of information security incident management, over a quarter of the reporting entities we surveyed had deficiencies related to this area. Specifically, 21 of the 77 survey respondents reported that they had not met or had only partially met the security standards for information security incident management. We also noted weaknesses while conducting our reviews. Three of the five reporting entities we reviewed have not met or have only partially met these requirements. For example, Entity C and Entity D did not have formally documented incident response plans. Rather, Entity C had developed a checklist of administrative steps that it would perform when it received notification of a potential breach. However, the checklist lacks critical components of an incident response plan, such as the protocols used to preserve evidence and thereby retain the ability to pursue legal action if appropriate, nor did it indicate Entity C’s intentions to test its incident response procedures to mitigate the impacts of actual incidents. Similarly, Entity D asserted that it relied upon the steps that the technology department had published for information security incident reporting. However, we found Entity D’s explanation problematic because incident reporting is only one component of the security standards related to information security incident management.

According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), two benefits of developing the capability to handle incidents are the ability to systematically employ a consistent approach that minimizes loss and the ability to learn from past incidents, thereby improving response to future attacks. However, until reporting entities develop comprehensive information security incident management plans, they cannot ensure that they are positioned to properly identify, respond to, and recover from information security incidents.

Most Reporting Entities Have Not Adequately Planned for Interruptions or Disasters

Losing the capability to process, retrieve, and protect electronically maintained information can significantly affect a reporting entity’s ability to accomplish its mission. If a reporting entity’s contingency planning controls are inadequate, even relatively minor interruptions can result in lost or incorrectly processed data, which may cause financial losses and expensive recovery efforts. For reporting entities involved in health or safety, some system interruptions can even result in injuries or loss of life. Given the severity of the potential consequences of system interruptions, it is critical that reporting entities have procedures for protecting their information resources and minimizing the risk of unplanned interruptions. Moreover, they must have a plan to recover critical operations should interruptions occur.

Nonetheless, the majority of reporting entities’ technology recovery planning efforts has fallen short of the security standards. As a result, these reporting entities cannot ensure that their critical information assets will be available following interruptions or disasters. The security standards require each reporting entity to develop a technology recovery plan (recovery plan) for activation immediately following a disaster to ensure the availability of critical information assets. Further, the security standards also require reporting entities to file copies of their recovery plans with the technology department at least once every two years. For this reason, we would have expected a high rate of compliance. However, only 23 of our 77 survey respondents stated that they have fully met the recovery plan requirements, while 32 respondents reported being mostly compliant. The remaining 22 respondents stated that they had not met or had only partially met these requirements.

We found similar deficiencies at the reporting entities we visited. Three of the five have only partially met the technology recovery plan requirements. For example, Entity A did not have a current business impact assessment, which is critical to developing an effective recovery plan. According to the security standards, a business impact assessment is the primary tool for identifying and prioritizing a reporting entity’s business functions and information systems; thus, it serves as the basis for developing a recovery plan. If a reporting entity fails to determine the order in which it should recover each critical system, it may expend its limited recovery resources on systems that are not critical to its mission. A one-day interruption of a major fee-collection system could significantly slow or halt a reporting entity’s receipt of revenues, diminish controls over millions of dollars, and reduce public trust; however, a system that monitors employee training might be out of service for several months without serious consequences. Further, sensitive data, such as personal information or information related to contract negotiations, may require special protection during a suspension of normal service, even if a reporting entity does not need the information on a daily basis.

Despite the importance of having a current business impact assessment, we found that Entity A’s business impact assessment was more than seven years old; thus, Entity A could not use it to fully develop its recovery plan. Although Entity A asserted that it had informally identified its mission-critical applications, it acknowledged that it had yet to formally assess and document them. Entity A stated that because it lacked an updated business impact assessment, it developed a recovery plan for only one of its departmental branches, rather than documenting a recovery plan that addressed the needs of the entire department. In fact, Entity A did not expect to complete its efforts to develop the recovery plan until January 2017.

Entity D had also only partially met the recovery plan requirements. For example, its recovery plan did not consistently identify a maximum acceptable time frame during which critical business applications could be inoperable. Further, its recovery plan did not contain detailed and systematic procedures for recovering its technology. Entity D also had not provided training to its personnel involved in technology recovery. Entity D asserted that it intended to modify its recovery plan to include these missing components at its next scheduled update.

In contrast to Entity A and Entity D, Entity B met most of the recovery plan requirements that we reviewed. Specifically, Entity B was able to demonstrate that it had updated its recovery plan three times within the past two years. Further, its recovery plan included a description of its critical business functions and their supporting applications, in addition to designations of the acceptable lengths of time each critical application could be unavailable for use. Moreover, Entity B’s recovery plan included detailed and systematic procedures for recovering its critical technology.

A recovery plan is critical for identifying the order in which a reporting entity should restore its information systems, the parties responsible for restoring them, and the resources needed to facilitate the restoration. During an emergency, a carefully developed recovery plan can help staff immediately begin the resumption of critical information systems and make the most efficient use of limited computer resources. Until reporting entities adequately maintain their recovery plans and train their staff, they cannot ensure the availability of critical information assets following an interruption or a disaster.

Many Reporting Entities Identified Similar Challenges in Meeting Information Security Requirements, and Some Described Best Practices for Achieving Compliance

The reporting entities that responded to our survey identified a number of challenges that had previously or were currently preventing them from achieving full compliance with the security standards. In analyzing the types of challenges reporting entities face, we identified two primary areas of concern—insufficient resources and competing priorities. However, other reporting entities shared best practices that we believe could assist the noncompliant reporting entities in addressing these challenges. By following best practices such as consulting with the technology department, networking with other reporting entities, and attending trainings, reporting entities may grow their information security skill sets and improve their information security posture using cost-effective means.

When asked to identify the barriers to compliance, 55, or 68 percent, of the 81 entities responding to this survey question asserted that they lacked sufficient resources to meet the security standards. They most commonly cited inadequate budgets, staff shortages, and a lack of technical expertise as factors contributing to their noncompliance. For example, one reporting entity stated that to attain full compliance with the security standards, it needed the ability to successfully implement over 700 information security controls identified in one of the NIST’s special publications. According to the reporting entity, it would require enormous resources and skill sets to implement and maintain these controls. Another reporting entity asserted that most small entities cannot afford to have an employee fully dedicated to information security and privacy, and consequently these entities must designate employees with other responsibilities to be their information security officers, whether they have the necessary skills or not.

However, 24 survey respondents stated that they overcame challenges related to a lack of resources by leveraging the knowledge of individuals external to their entities. Specifically, several reporting entities explained that they engaged with the technology department, either by discussing issues, asking questions, or using information on the technology department’s website. One reporting entity highlighted the importance of proactively establishing a working relationship with the technology department so that the lines of communication would be open if the entity needed assistance. Other reporting entities stated that they either contract with third-party vendors to acquire technical expertise or network with information security managers at other reporting entities to share knowledge about information security. For example, one survey respondent encouraged reporting entities to share information through interdepartmental groups. Likewise, another reporting entity explained that its agency hosts bimonthly meetings for the information security officers from all the departments within its agency to promote sharing of issues, solutions, and best practices.

Nine survey respondents also identified maximizing their internal information security training programs or participating in training for information security professionals as best practices that enabled them to achieve compliance. For example, two reporting entities indicated the importance of implementing information security awareness training to educate staff about their roles and responsibilities with respect to information security, and another entity stated that it benefited from attending training offered by the technology department.

The second trend we identified among reporting entities’ barriers to conforming with the security standards was competing priorities. For example, some reporting entities identified the need to juggle the competing priorities of supporting their day-to-day business operations and meeting the security standards. Twelve of the 81 survey respondents indicated that workload demands prevented them from focusing the necessary resources on becoming fully compliant. During our review, Entity D also expressed that competing priorities poses a challenge toward achieving full compliance. Similarly, another survey respondent explained that although the information security officer is responsible for assisting management in understanding the information security requirements, information security may not be management’s priority because management is focused on supporting the daily business operations. Thus, this respondent concluded that management’s “current mind set” is one barrier to achieving compliance with the information security and privacy policies.

In fact, six respondents identified the importance of garnering executive management’s support for information security as a best practice for achieving compliance with security standards. For example, a survey respondent indicated that executive support for information security is crucial; further, she explained that many of her colleagues believe their executives do not understand the need to dedicate resources to information security and privacy or feel that they cannot sacrifice operational needs to support it. Similarly, another survey respondent asserted that implementing the NIST’s risk management framework is an ambitious initiative, even for the most disciplined and resource-rich entities. He stated that executive leadership must be aware and supportive of their risk management programs in small entities such as his, because without that support, even minor implementation efforts become challenging. Finally, he stated that the success of a risk management program is dependent upon having a governance body in place early with champions to promote security initiatives.

In addition to identifying a lack of resources and competing priorities as barriers to the reporting entities’ compliance with the security standards, we identified various challenges related to the technology department’s guidance and oversight. We discuss these challenges in Chapter 2. Although some of the challenges reporting entities face in their efforts to comply with the security standards may be difficult to overcome, implementing appropriate security measures and controls is critical to ensuring the State’s ability to protect its information assets.

Recommendations

Entities A, C, D, and E

Entities A, C, D, and E should identify all areas in which they are noncompliant with the security standards, develop detailed remediation plans that include time frames and milestones, and ensure full compliance by August 2016.

Entity B

Entity B should identify all areas in which it is noncompliant with the security standards, develop a detailed remediation plan that includes time frames and milestones, and ensure full compliance by January 2016.

Chapter 2

The California Department of Technology Has Failed to Provide Effective Oversight of State Entities’ Information Security

Chapter Summary

The California Department of Technology (technology department) does not provide adequate oversight or guidance to state entities under the direct authority of the governor (reporting entities) for which it has purview. As a result, the technology department cannot ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of some of the State’s most critical information and information systems. As discussed in the Introduction, the technology department requires reporting entities to comply with the information security and privacy policies prescribed in Chapter 5300 of the State Administrative Manual (security standards). The technology department requires reporting entities to demonstrate their acknowledgement of the security standards and provide a measure of accountability by self-certifying whether they have met all necessary requirements each year. However, we found that 37 of the 41 survey respondents that certified full compliance to the technology department in 2014 were actually noncompliant with some of the security standards. The poor design of the self-certification form may have contributed to many reporting entities incorrectly reporting their compliance status.

Further, the technology department does not have a robust process for following up with entities that report noncompliance. As a result, many reporting entities have failed to resolve their known information security control weaknesses for years. In fact, we identified 18 reporting entities that had not certified compliance for at least five consecutive years. Although the technology department has certain enforcement tools at its disposal to compel noncompliant reporting entities to improve their information security controls, it has not developed policies or procedures for how and when it will use them. In addition, several reporting entities we surveyed indicated that the technology department does not provide them sufficient guidance, despite the various methods it uses to assist reporting entities in achieving compliance. Other reporting entities noted that certain mandated security standards are unclear, in part because the standards are located in a number of different documents. The technology department’s failure to provide adequate and executable guidance increases the possibility that reporting entities will continue to struggle to achieve full compliance. As a result, the State’s information remains at risk of being compromised for extended periods of time.

Finally, because the technology department has information security oversight authority only over state entities that report directly to the governor, many other state entities are not subject to its security standards or oversight. Consequently, we have identified information security for state entities that are not under the technology department’s purview as an area that warrants additional exploration.

The Oversight the Technology Department Provides to Reporting Entities Does Not Ensure the Safety of the State’s Information Assets

The oversight that the technology department provides to reporting entities has not produced a meaningful assessment of the State’s information security status, let alone safeguarded the State’s information assets. Specifically, our survey shows that a significant number of the reporting entities that certified full compliance with the security standards to the technology department in 2014 were not in fact compliant. Further, until recently, the technology department had not established a process for performing thorough follow-up activities with reporting entities that had yet to achieve full compliance, and the certification form that it currently uses lacks sufficient detail for it to understand the extent of reporting entities’ noncompliance. Finally, while the technology department has the authority to withhold the approval of new information technology projects for noncompliant reporting entities, it has not developed policies or procedures detailing the process or criteria it uses to decide when it should take such actions.

The Technology Department Has Been Unaware That Many Reporting Entities Have Deficiencies in Their Information Security

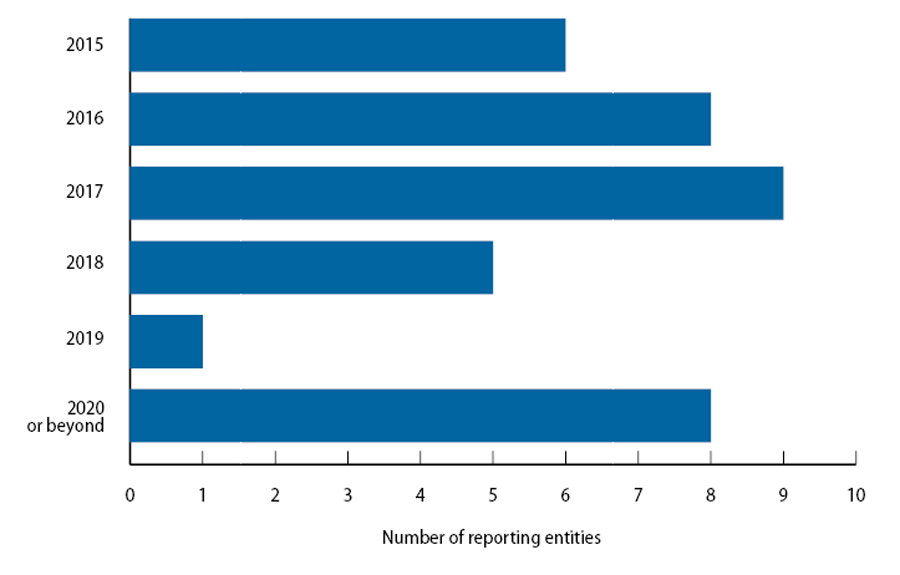

Nearly all of the reporting entities that certified full compliance with the security standards to the technology department in 2014 had deficiencies in their information security controls. As discussed in the Introduction, the technology department requires reporting entities to self-certify their compliance with the security standards annually to demonstrate their knowledge of these requirements and to provide a measure of accountability. Although 41 survey respondents certified to the technology department in 2014 that they had fully complied with all of the security standards, 37 of these entities acknowledged one or more areas of noncompliance when we surveyed them, and 17 of these 37 stated that they were not fully compliant with more than half of the security standards. Moreover, 23 of these respondents indicated to us that they would not achieve full compliance with the security standards until 2017 or later, as shown in Figure 4—with eight stating that they would not become fully compliant until 2020 or beyond.

Figure 4

Year by Which Reporting Entities That Misrepresented Their Compliance Status Expect to Achieve Full Compliance With the California Department of Technology’s Information Security Standards

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of survey responses from 37 of the 41 reporting entities that certified to the California Department of Technology in 2014 that they were in compliance with information security standards, but disclosed in our survey that they were not fully compliant.

When we conducted reviews of four reporting entities that certified to the technology department in 2014 that they were fully compliant with the security standards, we found a number of discrepancies in their actual compliance levels. Specifically, as discussed in Chapter 1, we identified various areas of noncompliance at all four of these reporting entities. Although each of these reporting entities asserted that they believed they were compliant with the security standards when they submitted their self-certifications to the technology department, they acknowledged areas of noncompliance as a result of our reviews. For example, Entity D stated that its staff has followed a consistent process to complete the self-certifications—staff review the form and make a determination as to the level of compliance. Further, Entity D asserted that, as a result of the changing requirements listed on the certification forms and updates to the security standards, its self-certification did not take into consideration all of the requirements of the security standards.6

Similarly, some survey respondents appeared to misunderstand their actual levels of compliance. Specifically, several asserted that they used the Information Security Risk Assessment Checklist that the technology department publishes on its website to assess their compliance with the security standards. However, according to the disclaimer on the technology department’s website, this checklist provides only a high-level view of common security practices and does not cover all of the steps reporting entities must take to complete the annual self-certification process. Consequently, reporting entities cannot rely upon the checklist alone to determine whether they have achieved full compliance with the security standards.

Summary of the California Department of Technology’s Pilot Information Security Compliance Audit Program

Purpose: To validate the implementation and operation of minimum baseline security controls articulated in state policy and standards for eight reporting entities.

Scope: The audit will examine and document compliance with information security requirements, including Chapter 5300 of the State Administrative Manual, the State Information Management Manual, and other state laws, regulations, policies, procedures, and standards.

Budgeted Hours (assumes one staff member per audit):

- Small-entity audit: 440 to 513 hours, or approximately three months.

- Medium-entity audit: 796 hours, or approximately five months.

- Large-entity audit: 1,646 to 3,142 hours, or approximately 10 to 20 months.

Examples of Requirements Tested:

- Risk management

- Asset protection

- Access control

- Incident management

- Human resources security

Source: California Department of Technology’s pilot information security compliance audit program.

Until the technology department develops a comprehensive self-assessment tool that reporting entities can use to evaluate their status in complying with the security standards, it risks continuing to receive inaccurate information from reporting entities. The certification form cannot effectively provide a measure of accountability if reporting entities fail to understand their true compliance status. Moreover, because the technology department does not have a true understanding of the compliance status of the reporting entities, it may make less informed internal policy decisions and its oversight may be less effective.

In response to our identification of its oversight as a high-risk issue in our 2013 report, and in recognition of the need to validate reporting entities’ self-reported compliance status, the technology department recently developed a pilot information security compliance audit program (pilot audit program). The text box provides a summary of the pilot audit program. The technology department began its first compliance review under the pilot audit program in February 2015; as of July 2015 it had begun auditing four of the eight reporting entities it had scheduled for review. The technology department estimates that it will take nearly a year and a half to complete its audit of these eight pilot entities. It stated that upon completion of the pilot audit program in June 2016, it will return to the Legislature with recommendations. However, at its current rate of four auditors completing eight audits every year and a half, it would take the technology department roughly 20 years to audit all of the 114 reporting entities.

Given the amount of time it would take the technology department to complete comprehensive information security audits for all reporting entities, it could also conduct—or require reporting entities to obtain—more frequent, targeted information security assessments. These assessments could include techniques such as electronic scans of operating systems, applications, and networks to identify vulnerabilities, and simulated real-world attacks to identify methods that actual attackers could use to circumvent the security features of a system, application, or network. By implementing more frequent information security assessments in addition to periodic comprehensive audits, the technology department could acquire a more timely understanding of the level of security that reporting entities have established for their high-risk areas.

The Technology Department Has Allowed Some Reporting Entities’ Information Security Weaknesses to Persist for Years

Until recent oversight improvements, the technology department lacked a process for conducting comprehensive follow-up activities with noncompliant reporting entities to help them achieve full compliance with the security standards. Consequently, it has allowed many reporting entities’ information security control weaknesses to persist for several years without holding the entities accountable for implementing remediation activities. In fact, we identified 18 reporting entities that either certified to the technology department that they were not fully compliant with the security standards or did not have a certification form on file for at least five consecutive years. By not establishing a robust process for following up with reporting entities that certify they are not in compliance, the technology department has allowed information security weaknesses to remain unmitigated, placing the State’s information at continued risk of misuse, loss, disruption, or compromise.

State law requires the technology department to coordinate the activities of reporting entities’ information security officers for the purpose of integrating statewide information security initiatives and ensuring the reporting entities’ compliance with the security standards. However, although the technology department tracks which reporting entities submit their annual Risk Management and Privacy Program Compliance Certification (certification form), it does not adequately follow up with reporting entities that certify they are not fully compliant. In fact, the technology department did not have a policy or procedure in 2014, the period under review, for reviewing the certifications it receives, including the remediation plans that it requires noncompliant reporting entities to submit.

The technology department’s lack of an adequate process for reviewing self-certifications and remediation plans is particularly problematic given the number of reporting entities that have struggled to achieve compliance with the security standards: More than 40 percent of the 114 reporting entities certified in 2014 that they had yet to achieve full compliance. We expected that the technology department would have followed up with these reporting entities to identify the barriers that prevented them from achieving full compliance or to evaluate the appropriateness of their remediation plans. However, when we reviewed the 2014 correspondence between the technology department and a selection of eight noncompliant reporting entities, we found that the technology department did not conduct any follow-up activities related to these reporting entities’ noncompliance status or remediation plans.

Further, when we reviewed certifications for reporting entities that were noncompliant in 2014, we identified 18 reporting entities that either did not have certifications on file or had certified that they were not fully compliant each year between 2010 and 2014. We reviewed correspondence between the technology department and two reporting entities that had certified their noncompliance every year since 2008 and found that the technology department rarely followed up on the reporting entities’ remediation plans. One of these reporting entities provides services to the public at state-owned facilities, and the other sets statewide policy related to critical state resources. As shown in Table 3, the technology department inquired about these reporting entities’ remediation plans on only three occasions between 2008 and 2014. Further, one of the reporting entities’ remediation plans remained relatively unchanged throughout this time frame, indicating that it was consistently noncompliant because of the same issues rather than because of new or evolving weaknesses. Because the technology department did not perform adequate follow-up activities to assist these reporting entities, it allowed their information security vulnerabilities to persist for at least six years.

Table 3

Years in Which the California Department of Technology Followed Up on Two Noncompliant Reporting Entities’ Remediation Plans

| Reporting Entity | Entity Description | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Provides services at state-owned facilities | ✔ | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| G | Sets statewide policy related to critical state resources | ✔ | X | X | X | X | ✔ | X |

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of correspondence between the California Department of Technology (technology department) and the reporting entities.

Note: In 2008 the Consumer Services Agency’s Office of Information Security and Privacy Protection (OISPP) had responsibility for providing direction related to information security. The OISPP became part of the Office of the State Chief Information Officer (OCIO) in May 2009. The OCIO was renamed the California Technology Agency in January 2011, which was then renamed the California Department of Technology in July 2013.

✔ = The technology department followed up on the reporting entity’s remediation plan.

X = The technology department did not follow up on the reporting entity’s remediation plan.

Our survey respondents also acknowledged the technology department’s failure to follow up on their remediation plans. Specifically, 30 of the 38 survey respondents that certified noncompliance in 2014 indicated in their response to our survey that they submitted remediation plans to the technology department.7 However, only four of the 30 reporting entities stated that the technology department performed any follow-up activities related to their remediation plans. Our survey also found that many reporting entities that certified noncompliance in 2014 continued to be noncompliant with the same requirements in 2015. In fact, as shown in Table 4, more than half of the reporting entities that indicated noncompliance in 2014 and 2015 did not comply with at least one of the five control areas we reviewed for both years.

Table 4

Information Security Control Areas in Which Reporting Entities Indicated Noncompliance in Both 2014 and 2015

| Select Information Security Control Areas | Percentage of Noncompliant Reporting Entities That Did Not Comply With Requirement Area |

|---|---|

| Information asset management | 55% |

| Risk management | 72 |

| Information security program management | 55 |

| Information security incident management | 55 |

| Technology recovery | 66 |

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of survey responses from 36 reporting entities that certified their noncompliance with information security standards to the California Department of Technology in 2014.

Note: Twenty-nine of the 36 reporting entities were noncompliant in both 2014 and 2015.

According to the technology department’s state chief information security officer (information security officer), a lack of resources has hindered its ability to conduct regular follow-up activities with reporting entities. However, she stated that in addition to establishing its pilot audit program (which we previously discussed), the technology department is currently in the process of formalizing procedures for reviewing reporting entities’ self-certifications and their corresponding remediation plans. Further, the technology department has drafted a new policy that would require noncompliant reporting entities to complete a standardized plan of action and milestones form (plan-of-action form) identifying their specific areas of noncompliance, plans for remediating the noncompliant areas, and timelines for achieving compliance. According to the information security officer, the plan-of-action form will allow it to identify and track the most common areas of noncompliance with the security standards across all reporting entities. The technology department plans to implement this new policy and the corresponding plan-of-action form by August 2015.

In the absence of comprehensive procedures for following up with noncompliant reporting entities, the technology department allowed information security weaknesses to continue, leaving the State’s information assets at risk. Given its role as an oversight authority, the technology department must lead by example and prioritize the implementation of the security standards for all reporting entities. In doing so, the technology department can convey the critical importance of information security to the State. However, by failing to follow up with reporting entities that certify they are not fully compliant, the technology department has demonstrated a lack of commitment in addressing information security risks.

The Technology Department Uses a Certification Form That Lacks the Detail Necessary for It to Support Struggling Reporting Entities

The form that the technology department requires reporting entities to complete when certifying their compliance with the security standards lacks sufficient detail to allow the technology department to identify specific areas of weakness. Instead, the certification form requires each reporting entity to choose between only two options when indicating its compliance status: It can check a box stating that it has implemented a fully developed risk management and privacy program that complies with all policy requirements in the security standards, or it can check a box indicating that it has not yet implemented all required components. As a result of this design, the certification form does not allow the technology department to identify reporting entities’ specific areas of noncompliance with the security standards. If the reporting entity chooses to certify its noncompliance, the technology department requires it to submit a remediation plan that identifies its areas of noncompliance, with timelines indicating when it will meet those specific requirements. However, the technology department currently provides no standardized format for reporting entities to report their remediation plan information. Consequently, reporting entities submit their own independently developed plans, which contain varying levels of detail and may not address all of the areas of noncompliance.

The certification form may also mislead reporting entities into believing that they are in compliance when they have not in fact met all of the requirements of the security standards. Specifically, the certification form includes 12 short descriptions of various information security policy requirements underneath the check box indicating full compliance with the security standards. However, we identified 64 different sections of the security standards with which reporting entities must comply, each of which contains one or more separate requirements. Thus, the 12 descriptions do not provide a comprehensive summary of all of the requirements for which reporting entities are certifying full compliance. As a result, reporting entities may certify that they have achieved full compliance without understanding the entire scope of the security standards. As previously discussed, we found that only four of the 77 respondents that completed our survey indicated that they were fully compliant with each of the 64 individual sections of the security standards, despite the fact that 41 of them had previously certified full compliance to the technology department in 2014.

The technology department intends to improve its certification process in part by having noncompliant reporting entities submit a standardized plan-of-action form, as we discussed previously; however, this solution may not fully address the certification form’s weaknesses. Specifically, this update will not improve the clarity of the certification form to ensure that reporting entities understand the entire scope of the policies. As a result, some reporting entities may not identify—and therefore not report—all of their areas of noncompliance on the new plan-of-action form, leaving the technology department without a complete and accurate picture of potential information security gaps statewide. Further, the certification form does not require reporting entities to submit any evidence supporting their self-reported compliance, such as policy documents, inventory records, or risk management plans. Consequently, the technology department cannot ascertain whether a reporting entity is truly compliant based on the certification form alone.

The Technology Department Does Not Have Policies That Define When and How It Should Use Its Enforcement Authority

The technology department lacks specific protocols defining when and how it should use its enforcement authority to encourage reporting entities to become compliant with the requirements set forth in the security standards. As we discuss in Chapter 1, 73 of the 77 reporting entities that responded to our survey acknowledged that they were not in full compliance with the security standards. When we asked the technology department’s director what enforcement authority the technology department had to compel these reporting entities to comply, he stated that it had several options to incentivize or enforce security compliance. Specifically, the technology department can reduce a reporting entity’s delegated cost threshold, which is the amount of money that the entity can spend on an information technology project without outside approval. It can also restrict a reporting entity’s access to the state information networks and data center. However, the technology department indicated that it had not used either of these actions solely because a reporting entity was out of compliance with the security standards, nor has it developed policies or procedures that define when it would use these actions.

Further, the technology department lacks policies and procedures for the two options the director indicated it had previously used to enforce compliance with the security standards. The director stated that the technology department has notified agency secretaries when one of the reporting entities under its authority is not compliant. Additionally, he stated that the technology department has used its authority to approve, suspend, or terminate large information technology projects to delay or deny such projects if the reporting entities initiating them were not compliant with the security standards. The responses we received from our survey support this assertion. Twenty-one reporting entities that certified noncompliance with the security standards in 2014 indicated that they had submitted at least one new information technology project to the technology department for approval since January 2010. Two of these 21 reporting entities stated that the technology department had delayed or denied their projects because of their noncompliance. However, the technology department does not have documented policies or procedures describing a process that it consistently applies to all projects to determine whether it will delay or deny those projects to compel reporting entities’ compliance. As a result, the technology department may not be considering information security uniformly across all of the new information technology projects it reviews.

The Technology Department Provides Insufficient Guidance to Assist Reporting Entities in Complying With the Security Standards

Although the technology department provides various resources to reporting entities to help them achieve compliance with the security standards, many reporting entities continue to struggle to understand the requirements. As discussed in the Introduction, the technology department developed the information security and privacy policies, standards, and procedures prescribed in Chapter 5300 of the State Administrative Manual to establish an information security framework for those reporting entities under its purview. To help reporting entities comply, the technology department provides resources such as training courses and policy templates. However, more than half of the 81 reporting entities that responded to our survey questions on this topic asserted that guidance and training were insufficient. Further, a significant number of reporting entities stated that some of the security standards are unclear. Others expressed concern that the security standards are not contained within a single document; instead, the requirements are located in a number of different documents. In the absence of clear requirements and adequate guidance, reporting entities will continue to face challenges in implementing the appropriate controls to safeguard the State’s information systems and the information they contain.

More than one-third of the reporting entities that participated in our survey stated that they do not understand all of the requirements prescribed in the security standards. In fact, 13 of the 38 survey respondents that certified noncompliance with the security standards to the technology department in 2014 indicated that they believe some of the requirements are unclear. Similarly, 15 of the 43 survey respondents that certified full compliance in 2014 expressed the same concern.8 For example, one survey respondent stated that many of the provisions of the security standards are ambiguous, confusing, and complex. It further noted that reporting entities can interpret these provisions in a number of different ways. Consequently, this survey respondent asserted that management may implement weaker interpretations of the security measures that do not meet the intent of the requirements.

We received similar feedback while performing our reviews. For example, Entity B—which we found to be either mostly or fully compliant in four of the five control areas we assessed—expressed concern about unclear requirements in the security standards and the other documents referenced by them. Specifically, the security standards require reporting entities to establish and maintain an inventory of their information assets. According to the requirements, each inventory must identify eight specific elements, including security categorizations and the potential consequences if the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of each information asset were compromised. The security standards reference guidance provided in one of the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) special publications for how to comply with these inventory requirements. However, NIST’s guidance for inventories appears to be limited to information systems, whereas the technology department defines information assets to include information systems, paper records, personal computers, software, and other assets.

This lack of clarity caused Entity B’s failure to comply with the security standards. Entity B explained that because of NIST’s guidance, it chose to apply the eight elements of an inventory only to its information systems and the data within each system. However, despite referring reporting entities to NIST’s guidance, the technology department indicated to us that reporting entities should apply the eight elements to all information assets, not just information systems. This discrepancy caused confusion and hindered the ability of Entity B to fully comply with the security standards.

When we asked the technology department what types of outreach it has performed to determine whether reporting entities understand all of the security standards, it stated that it provides various guidance materials on its website; consults with reporting entities to assist them in achieving compliance; and regularly sponsors various conferences, symposiums, trainings, and information security meetings with the reporting entities’ information security personnel. Further, as previously discussed, the technology department has begun auditing four reporting entities since February 2015 under its pilot audit program to validate their compliance with the security standards. Some survey respondents reported to us that the technology department has provided sufficient guidance and training, noting that its basic information security officer trainings, meetings for information security officers, and email communications regarding information security threats have been particularly helpful. However, one reporting entity asserted that although the quarterly information security professional meetings are beneficial, attending them is challenging due to the entity’s small size. Accordingly, this reporting entity stated that it would appreciate the ability to participate remotely via webinars or online training.

We asked the technology department whether it attempts to gather feedback on the clarity of the security standards and the effectiveness of its guidance. The technology department stated that it has frequent communication with the reporting entities during their annual self-certification of compliance, as well as at quarterly meetings. However, we believe—given the level of confusion reporting entities described to us in their responses to our survey—that the technology department should engage in a more robust outreach effort to find out what security requirements could be made more clear. Until it does so, many reporting entities may remain uncertain of their actual responsibilities under the security standards. This uncertainty increases the likelihood that noncompliant reporting entities will remain noncompliant, putting the State’s information assets at risk.

Some State Entities Are Not Subject to the Security Standards or the Technology Department’s Oversight

Despite the importance of ensuring the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the State’s information systems, the technology department does not oversee the information security of a large number of state entities. As discussed in the Introduction, the technology department has information security oversight authority for executive branch entities under the direct control of the governor. However, the technology department explained that current statute does not require state entities such as judicial branch entities, constitutional offices, and executive branch entities that are not under the direct control of the governor (nonreporting entities) to comply with the security standards. As outlined in the text box, several of these nonreporting entities maintain sensitive information and provide some of the most critical services in the State.

Examples of State Entities That Are Not Subject to California Department of Technology Oversight

California State Treasurer’s Office: Finances a variety of important public works needed for the State’s future, including schools and higher education facilities, transportation projects, parks, and environmental projects. The California State Treasurer’s Office also administers the State’s Pooled Money Investment Account, which invests money on behalf of state government and local jurisdictions to help them manage their fiscal affairs.

California State Controller’s Office: Provides fiscal control over more than $100 billion in receipts and disbursements of public funds a year, offers fiscal guidance to local governments, and investigates fraud and abuse of taxpayer dollars.

California Department of Justice: Represents the people of California in civil and criminal matters before trial courts, appellate courts, and the supreme courts of California and the United States. The California Department of Justice also coordinates statewide narcotics enforcement efforts; participates in criminal investigations; and provides forensic science services, identification services, and telecommunication support.

California Secretary of State’s Office: Oversees all federal and state elections within California, manages electronic filing and Internet disclosure of campaign and lobbyist financial information, maintains business filings, and safeguards the State Archives.

California State Board of Equalization: Administers tax programs that generated $56 billion in fiscal year 2012–13 and accounted for more than 30 percent of all state revenue. The California State Board of Equalization’s revenues support hundreds of state and local government programs and services, including schools, colleges, health care services, criminal justice programs, social welfare programs, transportation, and housing programs.

Source: California State Auditor’s (state auditor) review of the entities’ websites.

Note: The state auditor did not review these entities’ information security controls and is presenting them as examples only. Therefore, we are not drawing conclusions as to the strengths or weaknesses of these entities’ information security controls.

During previous reviews of two nonreporting entities, we identified significant deficiencies in the controls over their information systems. For example, in December 2013, we reported on the deficiencies in the controls the Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) and the superior courts had implemented over their information systems.9 Because the AOC and superior courts are not subject to the security standards, we evaluated their information system controls against the industry best practices contained in the U.S. Government Accountability Office’s Federal Information System Controls Audit Manual. We found that some of the AOC’s information security documents were either nonexistent or, in one case, had not been updated since 1997. In its reviews of the superior courts, the AOC repeatedly identified the same concerns with their plans, policies, and procedures, some of which dated back to 2003. We concluded that the weaknesses we identified, including practices we did not divulge in our report because of their sensitive nature, could compromise the security and availability of the AOC’s and superior courts’ information systems, which contain confidential information, such as court case management records, human resources data, and financial data.

Most recently, we identified weaknesses in the controls the California Public Utilities Commission (commission)—another nonreporting entity—has over its information systems. Our April 2015 report noted that although the commission is not subject to the security standards, its assistant general counsel stated that it complies with the security standards because they represent good business practices.10 Therefore, we used the security standards as the benchmark against which we evaluated the general controls the commission had implemented over its information systems. However, we found that the commission was missing a number of key information security documents or critical components of these documents. Specifically, the commission had yet to inventory all of its information assets, assess the risks to those assets, and develop an information security plan for mitigating those risks. Further, we reported that the commission did not have an incident response plan to ensure its timely response to and recovery from information security incidents such as malicious cyber attacks. Finally, although the commission had a current technology recovery plan, we questioned the plan’s usefulness because it failed to consistently identify critical applications, establish acceptable outage time frames for these applications, and develop strategies for recovery. We concluded that the commission had poor general controls over its information systems, compromising the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of its information.

On the other hand, many of these nonreporting entities may have implemented effective information security controls as part of their compliance with the state and federal laws that govern their programs. As a potential example, the California State Controller’s Office has published an information security program standards manual, which states that it was constructed to align with public and private sector best practices, including the Federal Information Processing Standards and NIST special publications. Accordingly, the California State Auditor plans to assess the information security risks associated with these nonreporting entities and, depending on the results, consider whether to expand the high-risk issue to include them.

Recommendations

Legislature

To improve reporting entities’ level of compliance with the State’s security standards, the Legislature should consider enacting the following statutory changes:

- Mandate that the technology department conduct, or require to be conducted, an independent security assessment of each reporting entity at least every two years. This assessment should include specific recommendations, priorities, and time frames within which the reporting entity must address any deficiencies. If a third-party vendor conducts the independent security assessment, it should provide the results to the technology department and the reporting entity.

- Authorize the technology department to require the redirection of a reporting entity’s legally available funds, subject to the California Department of Finance’s approval, for the remediation of information security weaknesses.

Technology Department