Audit Results

Laboratory Services Is Still Failing to Meet Its State Mandate to Oversee Clinical Laboratories

Over the last seven years, the California Department of Public Health’s (Public Health) Laboratory Field Services (Laboratory Services) has consistently failed to adequately oversee clinical laboratories (labs) as state law requires. In our September 2008 audit report titled Department of Public Health: Laboratory Field Services’ Lack of Clinical Laboratory Oversight Places the Public at Risk, Report 2007‑040 (2008 audit), we found that Laboratory Services was not sufficiently inspecting labs, monitoring proficiency testing, investigating complaints, or issuing sanctions. Similarly, in this follow‑up audit, we found that Laboratory Services has not inspected about half of the labs requiring such review under state law, and it continues to inconsistently monitor the results of proficiency testing for out‑of‑state labs. Additionally, Laboratory Services still struggles to investigate complaints promptly and issued only a small number of facility sanctions in the last seven years, although it oversees roughly 22,100 licensed and registered labs. Thus, it has not performed the oversight activities with which the State has entrusted it, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

Laboratory Field Services’ Implementation of the California State Auditor’s 2008 Recommendations Related to Its Oversight Responsibilities

| OVERSIGHT RESPONSIBILITY | 2008 FINDING | RECOMMENDATION | RECOMMENDATION’S CURRENT STATUS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inspections | Laboratory Field Services (Laboratory Services) had not conducted any biennial inspections of licensed clinical laboratories (labs). | Laboratory Services should inspect licensed labs every two years. | Partially implemented. |

| Proficiency Testing | Laboratory Services did not consistently monitor labs. Its policy and procedures were inadequate, specifically with respect to monitoring out‑of‑state labs and reviewing proficiency‑testing results in a timely manner. Laboratory Services did not identify or follow up on multiple deficiencies at labs. | Laboratory Services should adopt and implement policies and procedures for staff to promptly review proficiency‑testing results and notify labs that fail. It should follow specified timelines for responding to labs’ attempts to correct failures and sanction labs that do not comply. Further, Laboratory Services should monitor results of out‑of‑state labs’ proficiency testing. | Partially implemented. |

| Complaints | Laboratory Services’ policy and procedures lacked sufficient safeguards to ensure that staff promptly logged and investigated complaints and ensured that labs correct substantiated allegations. It also closed some complaints without investigation. | Laboratory Services should update its policies and procedures to add safeguards over receiving, logging, tracking, and prioritizing complaints as well as ensuring that labs correct all substantiated allegations. | Partially implemented. |

| Sanctions | Laboratory Services did not always have staff dedicated to sanctioning efforts, lacked management data, and could not demonstrate that it collected the civil money penalties it imposed. | Laboratory Services should sanction labs as appropriate and strengthen its sanctioning efforts by justifying, documenting, and collecting the civil money penalties it imposes. | No action taken. |

Sources: California State Auditor’s (state auditor) Report 2007‑040 and the state auditor’s analysis of Laboratory Services’ corrective action.

Laboratory Services Is Not Inspecting Labs as State Law Requires

Laboratory Services is still not performing inspections of clinical labs as state law requires. According to state law, Laboratory Services must inspect all licensed labs biennially, or no less than once every two years. However, similar to our finding in 2008, Laboratory Services is not meeting its mandate, only inspecting about half of the labs it is required to inspect.

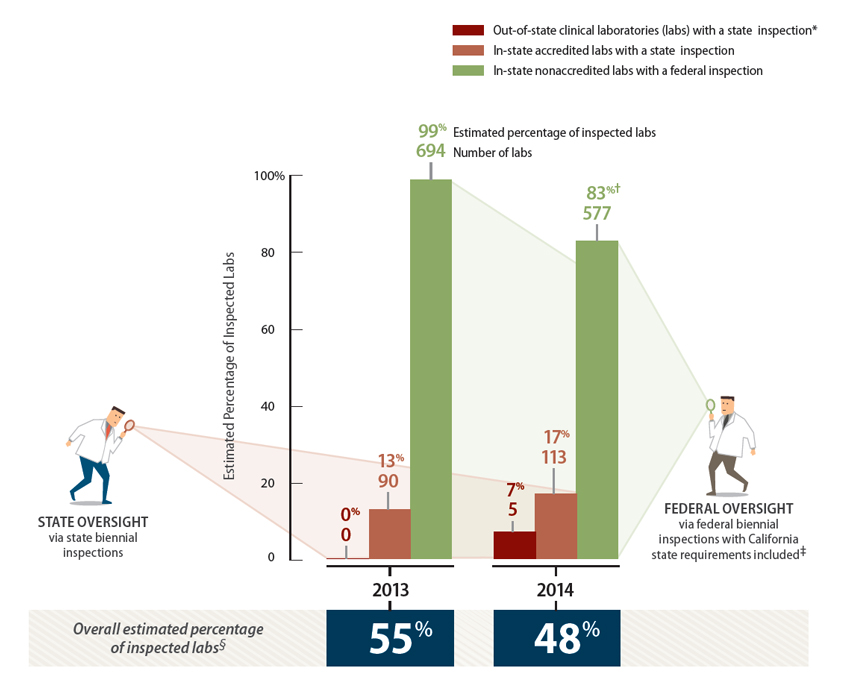

Over the last two years, Laboratory Services has not performed biennial inspections on a significant number of labs. Just over 2,800 labs require biennial inspections; thus, Laboratory Services must inspect about 1,400 labs each year. However, Figure 4 shows the percentage of licensed labs that Laboratory Services inspected in 2013 and 2014, demonstrating that it inspected only about half of the labs requiring biennial inspections in each year. For workload purposes, Laboratory Services divides its biennial inspection responsibilities into three lab segments: out‑of‑state labs, in‑state accredited labs, and in‑state nonaccredited labs. Laboratory Services maintains responsibility for inspecting out‑of‑state and accredited labs but relies on its Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 Section (CLIA section)—the unit that performs federal reviews on behalf of the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)— to inspect in‑state nonaccredited labs. Because state oversight requirements generally mirror CLIA, Laboratory Services views an inspection that its CLIA section performs as comparable.

Laboratory Services is far from meeting its obligation of inspecting all out-of-state and accredited labs once every two years. Its inspection rate for out-of-state labs—the smallest lab segment in its purview—is particularly problematic. State law has required out‑of‑state biennial inspections since 1996; however, the former chief of Laboratory Services reported that her staff did not begin performing out-of-state inspections until November 2014. The Los Angeles office performs out-of-state lab inspections and Figure 4, which we developed primarily from that office’s biennial inspection data, shows that Laboratory Services’ Los Angeles office did not inspect any out-of-state labs in 2013 and only five such labs in 2014. As a result, Laboratory Services failed to inspect at least 93 percent of out-of-state labs requiring biennial inspections in 2014. Going forward, Laboratory Services’ Los Angeles office plans to inspect two out-of-state labs each month. However, that plan will not reach the necessary number of lab inspections; instead, it will leave uninspected more than 60 percent of the 70 out-of-state labs requiring inspections.

Figure 4

Estimated Percentage of Clinical Laboratories That Received Either State or Federal Biennial Inspections in 2013 and 2014

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of Laboratory Field Services’ (Laboratory Services) inspection tracking logs and reports generated by the

federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Unaudited.

* Laboratory Services’ list of out-of-state labs for inspection numbered roughly 140 labs, which did not reconcile with its roughly 460 out-of-state

licensed labs. Nevertheless, the number of out-of-state labs inspected is so low that the differences between the lists do not alter our conclusion.

† Laboratory Services’ CLIA section—the unit that enforces federal law titled the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA)

and performs federal reviews on behalf of CMS—did not meet its inspection mandate for biennial inspections in federal fiscal year 2014. The CMS

performance review of that year recognized that the CLIA section operated with a shortage of inspectors during that year.

‡ When CLIA section examiners perform inspections related to federal oversight requirements, they also complete a state law checklist that allows

those inspections to count towards the State’s mandate of inspecting labs biennially.

§ These data are estimated because we converted CMS data from federal fiscal years to calendar years, which required using averages.

State oversight of accredited labs is also lacking: Laboratory Services inspected less than 20 percent of these labs in the last two years, as shown in Figure 4. Laboratory Services divides inspections of accredited labs between its two offices and has assigned inspections for Northern California labs to one staff person in the Richmond office who performed only eight biennial inspections during 2013 and 2014. This staff person’s logs show that he spent most of his time inspecting labs seeking state licensure as opposed to performing the recurring biennial inspections of currently licensed labs. Laboratory Services’ data show that it has currently assigned more than 250 clinical labs to its Richmond office.1 Assuming that roughly 125 of these accredited labs must be inspected each year, the single staff person in Richmond performing between three and five biennial inspections annually makes a negligible impact on the required workload.

Although Laboratory Services’ Los Angeles office has assigned inspections to a number of staff who perform significantly more biennial inspections of accredited labs than the single staff person in the Richmond office, it still falls far short of meeting its required workload. Data that Laboratory Services provided indicate that it has more than 600 clinical labs in Southern California that require recurring biennial inspections, translating to a need for it to perform roughly 300 biennial inspections each year. However, in 2013 and 2014, the Los Angeles staff only performed 87 and 108 biennial inspections, respectively, well under half of the required workload.

To meet its state mandate, Laboratory Services relies extensively on inspections that staff in its CLIA section perform. The CLIA section has seven state staff who perform federal‑based reviews on behalf of CMS. The CLIA section is shown in Figure 1 and is described in the Introduction. By counting CLIA inspections toward its requirement to perform recurring state biennial inspections, Laboratory Services has increased the number of labs inspected for state standards to around 50 percent, as Figure 4 shows. In response to one of our previous recommendations to improve efficiency, Laboratory Services began including CLIA inspections in its counts of completed biennial inspections as early as November 2008. When CLIA section staff perform federal lab inspections, they complete a one‑page state law checklist that Laboratory Services developed to determine whether the lab is also compliant with state standards. The state law checklist includes 15 criteria—some of which relate to requirements for lab personnel rather than lab facilities—that differ between California and federal laws and regulations. The CLIA section inspected 694 labs in 2013 and 577 labs in 2014. Without the inspections the CLIA section performed, the percentage of all clinical labs that received state biennial inspections would be significantly lower.

Laboratory Services claims that staffing is the main reason it has not inspected labs as required. The acting facility section chief in the Los Angeles office stated that she suggested hiring more staff as well as increasing the number of biennial inspections each staff member must perform every month in order to increase the total number of inspected labs. However, as we describe in a later section of the report, Laboratory Services has had both the funding and the opportunity to hire more staff since we completed the 2008 audit, but it has not done so.

Additionally, the former Laboratory Services chief stated that Laboratory Services did not perform out‑of‑state inspections before November 2014 because of the governor’s restriction on out‑of‑state travel. In April 2011 Governor Brown issued an executive order requiring that his office approve all out‑of‑state travel. However, we believe based on the criteria included in the executive order that Laboratory Services likely would have qualified for an out‑of‑state travel exemption. For example, the executive order stated that no out‑of‑state travel would be permitted unless it was at no cost to the State or was “mission critical,” meaning that, for instance, it pertained to a department’s enforcement responsibilities or to a function required by statute. Because state law mandates the biennial inspections, we believe that travel related to them would have qualified as mission critical. Moreover, state law requires that out‑of‑state labs reimburse Laboratory Services for travel and per diem costs to perform any necessary on‑site inspections; thus, the inspections would have incurred no travel costs to the State. Although Laboratory Services management believed it submitted out‑of‑state exemption requests, Laboratory Services and Public Health officials were unable to provide documentation of these requests. Further, the former Laboratory Services chief stated that as of May 2015 Laboratory Services had not sought reimbursement from the out‑of‑state labs for the costs of inspections. By consistently failing to perform a sufficient number of biennial inspections—a core component of its oversight responsibilities—Laboratory Services has demonstrated a pattern of not ensuring that labs adhere to state requirements.

Laboratory Services Has Minimized Proficiency Testing Monitoring for Out‑of‑State Labs

According to Public Health’s assistant deputy director of the Office of the State Public Health Laboratory Director, Laboratory Services did not adopt new proficiency‑testing policy and procedures (proficiency procedures) until March 2015—more than seven years after our 2008 audit. Further, it still has not addressed our recommendation in the 2008 audit that it promptly review the proficiency‑testing results of out‑of‑state labs. Monitoring labs’ proficiency testing provides Laboratory Services with insight into labs’ performance between biennial on‑site inspections.

Laboratory Services is responsible for monitoring proficiency testing for all state‑licensed labs regardless of their geographic location. However, Laboratory Services’ proficiency procedures minimize its oversight of out‑of‑state labs. According to the examiner in charge of licensing out‑of‑state labs, there are currently around 450 such labs, which represent around 16 percent of the licensed labs required to participate in proficiency testing. However, Laboratory Services’ proficiency procedures do not adequately help it determine how many failures an out‑of‑state lab may have or when those failures may occur. Further, the proficiency procedures do not explain how Laboratory Services obtains out‑of‑state labs’ testing results: The approach Laboratory Services has developed produces reports of test results only for labs located within California. The proficiency procedures do detail that Laboratory Services will verify during each out‑of‑state lab’s license renewal that it is enrolled in proficiency testing and that it is enrolled to test its proficiency in all areas corresponding to the testing it performs. However, these functions are not the same as monitoring results from proficiency testing.

We did see evidence that Laboratory Services reviews the results of proficiency testing for out‑of‑state labs when it renews the labs’ licenses. Nevertheless, the proficiency procedures call for Laboratory Services to review the results every 30 days from in‑state labs that reported results during that 30‑day period. According to the clinical labs facility section chief of the Richmond office (facility section chief) who manages facility licensing including proficiency testing, the less frequent monitoring of out‑of‑state labs is not a problem because CMS agents in the states where these labs are located monitor them for CLIA purposes, so the risk that deficiencies will go undetected is low. Even so, Laboratory Services’ current responsibility is to know which out‑of‑state labs have failed proficiency testing so it can take appropriate action; its reliance on federal monitoring under CLIA highlights the redundancy of Laboratory Services’ oversight in this area.

Notwithstanding the limitations of its monitoring of proficiency testing for out‑of‑state labs, Laboratory Services has addressed certain aspects of our recommendations concerning its proficiency procedures for in‑state labs. For example, the proficiency procedures it implemented in March 2015 specify how often it should review proficiency‑testing results and what steps it should take to ensure that labs take timely corrective action, and they outline sanctions when labs do not correct problems. Additionally, we reviewed 10 testing failures for in‑state labs that occurred in 2014 and found that Laboratory Services had identified them, contacted the labs, received responses within the time periods set in the proficiency procedures, and accepted the labs’ plans to resolve the deficiencies within reasonable periods of time.

Laboratory Services’ Complaint Procedures Still Need Enhancing

Laboratory Services has not successfully modified its complaint procedures in response to our prior audit. In 2008 we recommended that Laboratory Services address weaknesses in its complaint investigation practices and its related policy and procedures. Our recommendations were aimed at helping Laboratory Services track and prioritize complaints while also ensuring that substantiated allegations were corrected. Laboratory Services’ records show that it received an average of 177 complaints annually from 2008 through 2014. However, it still has not established time frames for completing complaint investigations, and some lower priority complaints may never be investigated. Finally, Laboratory Services has not defined in its procedures when its staff should revisit labs to verify that they have successfully corrected the most significant problems substantiated during complaint investigations.

Although seven years have passed since we recommended to Laboratory Services that it strengthen its complaint procedures, it has not adequately addressed all of our concerns. Specifically, we expected to find that Laboratory Services had established time frames to ensure that it completes complaint investigations promptly, but it has not done so. We reviewed Laboratory Services’ complaint logs from January 2014 through April 2015; these logs show that it received 218 complaints and that 13 were open as of May 2015. We reviewed five of these open complaints and found that Laboratory Services had not, in our view, promptly addressed two of them. Each of the two complaints alleged that the labs had not properly supervised unlicensed laboratory personnel, yet as of May 21, 2015, neither complaint had been closed or investigated. Laboratory Services received the first complaint in April 2014 and the second in October 2014; therefore, it had left complaints unresolved for 10 months to over a year.

When we inquired about these two complaints, the examiner tasked with performing the investigations stated that he had not done so because the investigations would involve several examiners observing the labs for extended periods of time. The examiner further explained that he did not ask his supervisor for approval to conduct extended observations or for staff support because he did not think the supervisor would approve his requests. The lack of documentation explaining why Laboratory Services did not perform these complaint investigations, along with the fact that management did not approve the examiner’s decision, highlights Laboratory Services’ informal complaint process in which examiners appear able to determine, without further management review, which complaints are worthy of investigation.

Laboratory Services’ complaint procedures also do not address our concerns from the 2008 audit regarding the receipt and prioritization of complaints. Specifically, the complaint procedures still allow any employee to accept complaints, which as noted in our 2008 audit, increases the risk that Laboratory Services will lose a complaint or overlook a matter of serious concern. The complaint procedures also state that the lowest priority complaints will be investigated at the next on‑site inspection. Even though licensed labs do require biennial inspections, state law does not require registered labs to be routinely inspected. As a result, Laboratory Services is potentially leaving the lowest priority complaints it receives uninvestigated for up to two years for licensed labs and indefinitely for registered labs. Furthermore, because Laboratory Services does not inspect a high percentage of licensed labs, it may not investigate at all complaints it classifies as low priority.

Finally, Laboratory Services’ complaint procedures continue to lack detail regarding when its staff should ensure that labs take corrective action in response to completed investigations. In particular, the complaint procedures do not discuss when performing another on‑site inspection is warranted to ensure that the offending lab has corrected significant deficiencies— those that place a patient’s health at risk. Although we reviewed five complaints that Laboratory Services had substantiated through its investigations and noted that it performed a follow‑up on‑site inspection in each case, the lack of clear guidance increases the risk that examiners may not verify a lab’s efforts to correct even the most egregious of cases. Even though Laboratory Services deserves credit for the follow‑up inspections it performed, we continue to believe that it could enhance its policies by setting clearer expectations defining when its examiners should visit labs to verify that significant problems no longer exist.

Laboratory Services Has Failed to Strengthen Its Sanctions Activities

Laboratory Services has failed to respond to our 2008 recommendations that it guide staff in using its sanction authority, including ensuring that labs comply with sanctions by, for example, paying the imposed fines. We previously reported that Laboratory Services imposed 23 sanctions in the form of civil money penalties from 2002 through 2007; however, we identified only four facility‑related sanctions that Laboratory Services imposed since our 2008 audit. Further, it did not collect any civil money penalties in fiscal years 2012–13 and 2013–14. With Laboratory Services having oversight of almost 2,800 licensed labs, we are skeptical that so few labs actually required sanctioning— such as civil money penalties or revocations of their licenses or registrations—in the last seven years. Overall, it appears that Laboratory Services’ sanctioning process suffers from inconsistent staffing and unreliable records regarding past sanctions activity, leading to Laboratory Services’ inability to determine whether it collected in full the civil monetary penalties it imposed. Further, we believe Laboratory Services needs to develop a more robust sanctioning process, such as one that involves multiple managers who monitor sanction activity and collections, in order to guard against the potential for fraud.

Laboratory Services’ former chief stated that since our 2008 audit Laboratory Services has not always had staff dedicated to sanctioning efforts, noting that the most recent manager responsible for sanctioning held that duty for just one year before retiring. We also found that Laboratory Services has not updated its sanction policies since 1998. Two sanction cases we reviewed illustrate Laboratory Services’ lack of adequate processes that would allow it to sanction labs effectively. In the first case, we found that Laboratory Services did not promptly sanction a lab for willful and unlawful conduct when it employed and used unlicensed lab personnel to conduct tests and analyses. Laboratory Services received a complaint about this particular lab in February 2014, and after performing an on‑site inspection in March 2014, notified the lab in May 2014 that it had confirmed the allegation. Nevertheless, in May 2015—one year after it confirmed the wrongdoing— Laboratory Services was still drafting a letter indicating its intent to impose a monetary penalty on the lab. Laboratory Services further delayed issuing the sanction letter by a month when its former chief retired. It ultimately mailed the letter in June 2015 and notified the lab of its intent to impose a $14,150 civil money penalty, plus an additional $7,500 to recover the costs of its investigation. By not promptly sanctioning the lab in this case, Laboratory Services showed its ineffectiveness at ensuring that labs adhere to state requirements.

In the second sanction case, Laboratory Services could not provide documentation that a sanctioned lab had paid its civil money penalty in full. Laboratory Services imposed a sanction on a high‑profile lab for willful and unlawful conduct for not having a lab director responsible for operations, for employing an unlicensed person who performed complex tests, and for submitting false statements on lab‑licensing documents. Following a legal dispute with Public Health about this sanction, the lab agreed to pay $40,000 in 40 monthly installments of $1,000 from February 1, 2009, through May 1, 2012. However, the accounting reports that Laboratory Services provided to us did not account for $5,000 of the $40,000 penalty, and the former chief stated that Laboratory Services searched its records and could not find documentation indicating whether the lab paid the remaining $5,000. She offered the explanation that any supporting document might have been destroyed per Public Health’s records retention policy. She also stated that Laboratory Services did not develop a final notice documenting that the lab paid the penalty in full. Although it is possible the lab paid the full amount, Laboratory Services’ inability to resolve our questions concerning the receipt of the $5,000 demonstrates that it needs to strengthen its record keeping.

Laboratory Services’ lack of assigned staff, outdated processes, and unreliable data leave its sanctioning process vulnerable to mistakes and susceptible to staff engaging in fraudulent acts. Although we found no evidence of fraud, we noted that only one staff person knew the status of outstanding sanctions and other staff were required to turn to this person for answers to our questions about the sanctions process. For example, Laboratory Services’ staff were unable to provide a sanction database that was purported to track civil money penalties since, according to an associate governmental program analyst, only the one staff member in question had access to the file.

Further, once Laboratory Services provided us with the sanction database, we found that the data it contained were inconsistent with Laboratory Services’ official accounting reports. For example, the database showed that one lab paid a $92,840 penalty in June 2011; however, the accounting reports showed the penalty payment was posted to Laboratory Services’ Clinical Laboratory Improvement Fund (fund) but then reversed, thus cancelling the entry. Laboratory Services was unable to provide documentation that demonstrated where and if the funds were ever deposited, and Public Health’s accounting unit did not respond to our requests for further documentation and clarification about the reversing entry. With sanction records that cannot be easily compared with official accounting records, and with access to sanction information generally limited to one staff person, Laboratory Services’ sanction process is at risk for fraud and abuse. Because it continues to face challenges in its sanction program seven years after our 2008 audit, it is clear Laboratory Services has not addressed the concerns we raised at that time.

Management of the Laboratory Services Program Is Inadequate

Laboratory Services has also failed to respond to the recommendations we made in our 2008 audit for it to better manage its resources; consequently, problems that existed more than a decade ago still plague it. We found that mismanagement caused Laboratory Services to collect improper fee amounts from labs, to waste opportunities to partner with accreditation organizations that could boost lab oversight, and to fail to address hiring and retention issues in the face of an aging workforce. Laboratory Services has also taken little or no action to address several other recommendations we made, including those to improve its disjointed information technology systems and to update its outdated regulations, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3

Laboratory Field Services’ Implementation of the California State Auditor’s 2008 Recommendations Related to Its Management Responsibilities

| MANAGEMENT RESPONSIBILITY | 2008 FINDING | RECOMMENDATION | RECOMMENDATION’S CURRENT STATUS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fee Adjustment | Laboratory Field Services (Laboratory Services) incorrectly adjusted clinical laboratory (lab) fees for three of the five years analyzed. | Laboratory Services should adjust its fees in accordance with the State’s annual budget act. | No action taken. |

| Accreditation Organizations | Laboratory Services had not approved any accreditation organizations to help it oversee labs and meet its mandate. | Laboratory Services should use accreditation organizations to help it perform inspections. | Not fully implemented. |

| Hiring and Succession Planning | Laboratory Services attributed its inability to meet its mandated responsibilities to a lack of resources. It specifically identified inadequate staffing as a concern. | The California Department of Public Health, in conjunction with Laboratory Services, should ensure that Laboratory Services has sufficient resources to meet all its oversight responsibilities. | Not fully implemented. |

| Information TechnologyLaboratory Services’ information technology data systems did not adequately support its activities, such as tracking all aspects of its complaints and sanctions activities. The information technology systems lacked safeguards to ensure that data were accurate and could be used by management. | Laboratory Services should ensure that its information technology systems support its needs, and if it continues to use internally developed databases, it should develop and implement appropriate system controls. | Laboratory Services should ensure that its information technology systems support its needs, and if it continues to use internally developed databases, it should develop and implement appropriate system controls. | No action taken. |

| Regulations | In three instances, Laboratory Services maintained state regulations that state law had superseded. | Laboratory Services should update, repeal, and revise its regulations as necessary. | No action taken. |

Sources: California State Auditor’s (state auditor) Report 2007-040 and the state auditor’s analysis of Laboratory Services’ corrective action.

Laboratory Services Is Overcharging Licensed Labs

Laboratory Services has continued to fail to correctly adjust its license fees, which has resulted in it overcharging labs more than $1 million. State law requires Laboratory Services to adjust its license and registration fees by percentages specified in the State’s annual budget act; however, the Legislature created a sliding schedule for license fees in 2009, which raised the fees, and since then license fees have been excluded from the annual budget act adjustment. We identified three errors Laboratory Services made since our 2008 audit. Laboratory Services’ most egregious error occurred in January 2014 when it implemented an unauthorized license fee increase of more than 13 percent. We estimate this error resulted in labs collectively overpaying the State more than $1 million in fees. Further, since posting the increased license fee in January 2014, Laboratory Services has continued to charge labs these erroneous fee amounts. We determined that Laboratory Services did not realize that the percentage increase did not apply to license fees, as specifically stated in the annual budget act.

Laboratory Services does not have well‑defined processes in place to ensure that it analyzes annual budget act changes accurately. We recommended in our 2008 audit that Laboratory Services should work with Public Health’s budget section to ensure that it adjusts fees in accordance with the budget act, and we had concluded in September 2009 that it fully implemented this recommendation based on information it had provided to our office. However, the unauthorized increase we identified during our follow‑up audit has caused us to conclude that Laboratory Services needs to take additional action, particularly in light of recent retirements of key staff. For example, our review of Laboratory Services’ procedures revealed only a high‑level, one‑page document that did not describe who was responsible for coordinating with Public Health’s budget section to ensure that Laboratory Services implemented the correct fee adjustment each year. Moreover, when we tried to obtain Laboratory Services’ perspective on the improper increase, the facility section chief informed us that she was not involved in the fee calculations and that the employee who prepared the calculations had retired from Laboratory Services. The facility section chief stated that Laboratory Services’ former chief oversaw the fee increase process; however, the former chief also had retired. Key staff retirements only reinforce the need for Laboratory Services to have a clearly defined and well‑understood process for increasing fees, which would include identifying those staff responsible for coordinating with Public Health’s budget section and the steps for verifying that the proper authorization exists in the annual budget act to execute fee changes.

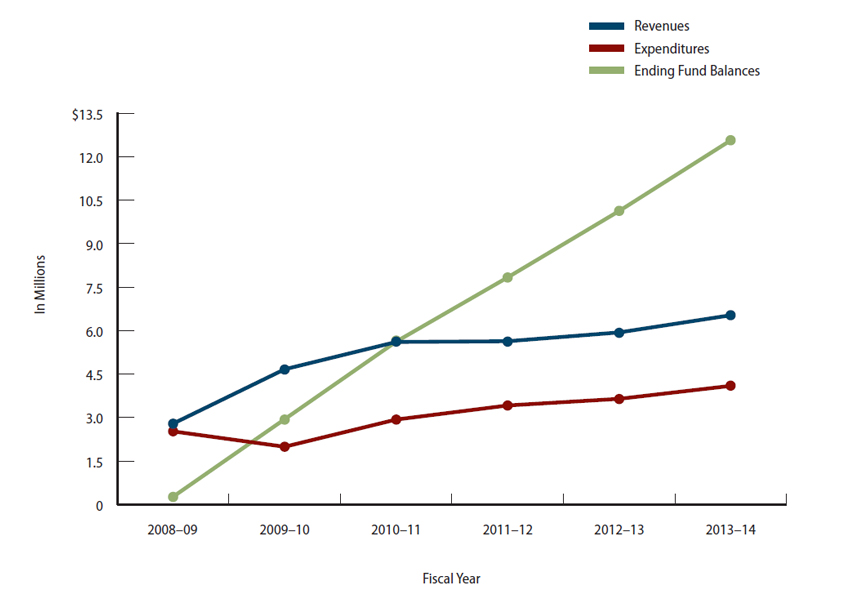

Further, Laboratory Services’ revenue from license and registration fees has far exceeded its oversight costs. For fiscal years 2008–09 through 2013–14, Laboratory Services collected a total of about $31.2 million in license and registration fees while spending only $18.6 million to monitor labs. As a result, Laboratory Services collected roughly $12.6 million in fee revenue that it did not need for the level of oversight it provided. Figure 5 shows that Laboratory Services’ revenue collection for its fund has consistently exceeded its expenditures. Laboratory Services’ excess license and registration revenue may be in part due to Public Health’s decision to sponsor legislation establishing higher fees. In sponsoring this legislation, it argued that Laboratory Services did not have the resources necessary to adequately enforce state law by conducting inspections and investigating complaints. In October 2009 the new law became effective, but as we describe elsewhere in this report, Laboratory Services continues not to meet its oversight mandates despite the increased fees as reflected in its growing fund balance.

Moreover, Laboratory Services’ problems with overcharging labs may extend to overcharging the lab personnel who also pay fees. To qualify to perform lab work, state law requires certain lab personnel be licensed by Laboratory Services, which charges fees for the licenses. In addition to paying a fee, an individual must meet educational and training requirements and pass examinations. As of June 30, 2014, the fund’s total ending balance—for lab license and registration and personnel licensing—exceeded $19.3 million. Although at least $12.6 million of that balance pertained to Laboratory Services’ overcharging of labs, the remaining amounts may be due to Laboratory Services’ excessive revenue from personnel fees.

According to Laboratory Services’ health program manager, who is responsible for managing Laboratory Services’ accounting unit, the disparity between Laboratory Services’ licensing revenue and expenditures relates to its unfilled examiner positions. However, this explanation differs from the explanation Laboratory Services provided during our 2008 audit. At that time we inquired about Laboratory Services’ fund balance with the former assistant deputy director of the Center for Health Care Quality (former deputy director) who oversaw Laboratory Services. The former deputy director asserted that Laboratory Services would use the excess money in its fund for one‑time investments to help it stabilize the program, such as replacing Laboratory Services’ information technology systems. However, seven years later, Laboratory Services continues to have vacant facility examiner positions and has yet to replace its information technology systems. Although we would expect Laboratory Services to maintain a prudent reserve, such as an amount equaling 5 percent of its annual expenditures or about $420,000, Laboratory Services’ reserve exceeded $18 million as of June 30, 2014. With such a high reserve, the labs that pay fees to Laboratory Services may reasonably question the State as to the fairness and appropriateness of those fees in relation to the actual expense incurred for oversight.

Figure 5

Laboratory Field Services’ Revenues, Expenditures, and Ending Fund Balances Related to Its Oversight of

Clinical Laboratories

Fiscal Years 2008–09 Through 2013–14

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of Laboratory Field Services’ accounting reports.

However, resolving Laboratory Services’ excessive reserve may prove difficult. A gap exists in state law such that Laboratory Services lacks the authority to ensure that its lab fees are consistent with the costs of oversight. On one hand, according to statute, Laboratory Services may charge only the amounts needed to cover its costs; the law states that total fees collected shall not exceed the costs incurred for licensing, certification, inspection, or other activities relating to the regulation of labs. On the other hand, the Legislature currently uses the budget act to annually prescribe license and registration fee adjustments. Consequently, our legal counsel has advised that Laboratory Services lacks the authority to reduce its fees when its revenues exceed its costs. Based on its high fund balance at the end of fiscal year 2013–14, we estimate that Laboratory Services could suspend lab fee collection for the next three years and still have money remaining in its fund. Nevertheless, it is unclear what steps Laboratory Services can take to better align revenue with costs, such as lowering its fees or temporarily suspending them. We believe that the fees a regulated community pays should align with actual costs. Further, when fee revenue greatly exceeds costs, it is prudent for the State to achieve equilibrium in the most expeditious and administratively simple way possible.

Laboratory Services Has Failed to Partner Effectively With Accreditation Organizations

Laboratory Services has wasted opportunities to work with accreditation organizations to help it fulfill its oversight responsibilities. Under state law, Laboratory Services can approve private nonprofit accreditation organizations to conduct oversight functions—including performing inspections and monitoring proficiency testing—in lieu of its direct oversight. However, Laboratory Services has not taken full advantage of this opportunity, despite an internal analysis showing the potential positive effects on its workload and on its ability to meet its mandates. In an internal memo to the former chief of Laboratory Services dated February 2015, the former section chief of the Los Angeles office noted that six different accreditation organizations have accredited labs operating in California. The former section chief concluded that approving the six accreditation organizations would have a major impact on Laboratory Services’ workload. For example, approving the six accreditation organizations would reduce the number of labs requiring inspection by 1,254 and create a staffing surplus at Laboratory Services. The internal memo also acknowledged that with a limited staff of three performing inspections, the Los Angeles office was completing only 39 percent of its required workload. However, our follow‑up audit found that Laboratory Services has approved only one accreditation organization, and it lacks a documented agreement formalizing that organization’s responsibilities for monitoring labs’ compliance with California law.

Laboratory Services has also not developed a process to approve and oversee accreditation organizations. A 2009 law clarified Laboratory Services’ existing authority to use accreditation organizations to help it with its oversight mandate. The 2009 law outlined application requirements and gave Laboratory Services about 15 months to develop and implement a program. As seems reasonable with any new agency initiative, we expected Laboratory Services to develop a plan including policy and procedures for accepting, processing, and approving accreditation organizations’ applications. We also expected Laboratory Services to establish plans for monitoring accreditation organizations’ performance after approval, including processes to periodically reauthorize each accreditation organization and revoke authorization when necessary. Ideally, these plans would contain detailed safeguards— such as multiple application reviewers, set time frames, and performance measures—that would help ensure that the processes were consistent and effectively managed. The 2009 law specified that Laboratory Services could issue its plan to use accreditation organizations through an All Clinical Labs Letter, which would take effect 45 days following publication. Despite the potential for this alternative regulatory process to be more streamlined than the process that Public Health would typically have to follow to implement new regulations, Laboratory Services did not use the authority the 2009 law granted it.

With no formal application review process in place, we noted that the applications of other accreditation organizations have awaited Laboratory Services’ decisions far beyond the time frame established in statute. State law required Laboratory Services to begin accepting applications from accreditation organizations on January 1, 2011, and to make a determination within six months of their receipt. Although Laboratory Services started accepting applications on time, it has failed to make determinations on all but one of the applications it has received. Four accreditation organizations submitted applications, and Laboratory Services took 20 months to approve one. It was still reviewing two of the other applications as of April 2015, nearly four years later. According to Laboratory Services’ former chief, the fourth and final application was withdrawn. She stated that she and a retired annuitant accepted and reviewed applications until July 2014, when the retired annuitant left Laboratory Services. At that time, the former chief assumed sole responsibility for reviewing and approving the accreditation organizations’ applications until her own retirement in May 2015. After the former chief retired, the assistant deputy director stated that she transferred the review of the remaining applications to two CLIA section staff, including the section chief, with the goal of responding to the accreditation organizations by the end of July 2015. However, when we followed up with the assistant deputy director at the end of July 2015, she stated that Laboratory Services would not meet the goal for responding to the accreditation organizations due to the sheer volume of information in the application packets and that it did not have a date for potential approval.

For the one approved accreditation organization, Laboratory Services has not established or documented clear expectations for how it will monitor the organization’s performance and transfer its oversight responsibilities. Although it granted the accreditation organization approval in August 2013, Laboratory Services has not entered into an agreement with it specifying the organization’s role and responsibilities or establishing how Laboratory Services, through oversight, will verify that it is performing acceptably. When we inquired about the status of Laboratory Services drafting and signing agreements with approved accreditation organizations, we received conflicting viewpoints. The assistant deputy director recognized that relying on accreditation organizations for lab oversight involved some risk, and she stated that she would be more comfortable if a memorandum of understanding existed between the approved accreditation organization and Laboratory Services. In contrast, the former chief stated she believed that the existing statute outlines the responsibilities of the accreditation organization, thereby implying that additional formal agreements were unnecessary.

Despite its internal analysis outlining the benefits of using accreditation organizations for oversight, Laboratory Services has not capitalized on this opportunity. Specifically, it has no guidelines to review and approve accreditation organizations’ applications, no documented plans to monitor their performance, and no formal agreement to ensure that responsibilities are clearly articulated to facilitate accountability. With Laboratory Services’ inspection responsibilities largely unmet, we find it surprising that it has not prioritized using accreditation organizations.

Laboratory Services Faces Significant Staffing Challenges and Has Failed to Plan for Retirements Through Succession Planning

Over the past seven years, Laboratory Services has not resolved the issues that it claimed have kept it from having sufficient staffing to meet its mandate. For example, during our 2008 audit, Laboratory Services explained that it did not plan to conduct regular inspections of labs every two years unless it received additional resources, noting at the time that it had only three examiners focused on investigating complaints and inspecting labs for initial licensure. In January 2014 Laboratory Services’ management drafted a recruitment and retention proposal that aimed to increase employee salaries and thus make the examiner position more attractive to both future and current employees. However, that proposal did not pass the internal scrutiny of Public Health’s human resources branch because of inadequate evidence demonstrating that Laboratory Services has a recruitment and retention problem. Further, two years earlier in 2012, Laboratory Services lost its authority to fill 15 open examiner positions when the California Department of Finance directed that it eliminate these positions because they had been vacant for an excessive period of time. With many examiners and managers now older than 60 and approaching retirement, Laboratory Services faces a significant succession planning problem that it has not successfully managed since we last raised these issues in our 2008 audit.

Laboratory Services claims that raising salaries will improve its ability to hire and retain staff. In responding to the recommendations from our 2008 audit, Laboratory Services’ management repeatedly stated that salaries were a barrier to staff recruitment and retention. In its January 2014 proposal, Laboratory Services’ management wrote that the salaries for its examiner staff had lagged behind the private sector for years and if Public Health did not approve the proposal, the salary imbalance would cause Laboratory Services to continue to lose qualified examiner staff. The proposal further warned that the lax oversight that would inevitably result from the overextension of its shrinking examiner staff would compromise Laboratory Services’ ability to assure high‑quality laboratory testing and health care for the people of California.

However, Laboratory Services has yet to convince the human resources branch within in its own department that it has a compelling argument for requiring higher salaries. The chief of Public Health’s human resources branch (human resources chief) and her staff reviewed the proposal and responded in January 2014, concluding that Laboratory Services’ proposal lacked compelling evidence for the requested salary increase. Although not disputing the need for more examiners, the human resources chief concluded that Laboratory Services already had sufficient resources to fill its current vacancies, noting for example that it had 43 candidates on its hiring lists for six open examiner positions. She stated that Laboratory Services needed to demonstrate through evidence that it either sent the individuals on these hiring lists contact letters and they waived their interest in employment or that it interviewed them and found them to be unsuitable for employment. According to the human resources chief, Laboratory Services could not defend its contention that it had a recruitment problem without such documentation. She was equally skeptical that Laboratory Services had a retention problem, noting that since July 1, 2007, only one examiner had resigned and one failed probation, with the remaining separations resulting from retirements. Summing up her evaluation of the proposal, she stated that Laboratory Services needed to do more than just make a request and issue statements; it had to defend its position with more data.

Before Laboratory Services had even made an internal proposal to increase salaries for its examiners in 2014, the Legislature authorized it to hire 16 new examiners for lab facility oversight pursuant to the 2010 Budget Act (Chapter 712, Statutes of 2010). However, according to the former chief, it was unable to fill the new positions the Legislature approved because the governor implemented a hiring freeze in February 2011, four months after the 2010 Budget Act was passed and Laboratory Services gained the authorization to hire. Although it appears to us that Laboratory Services may have been eligible for an exemption from the hiring freeze based on the criteria set forth by the governor’s office, the former chief only provided documentation supporting one exemption request for one examiner position focused on lab facilities. Given Laboratory Services’ long‑standing claims that it needed additional staff to meet statutory requirements for lab oversight, and given that funding for this oversight comes from the fees that labs pay, we believe Laboratory Services could have made a strong case for an exemption from the governor’s hiring freeze, thus increasing the number of examiners dedicated to lab oversight.

Today, Laboratory Services has a significant number of examiners approaching retirement, yet it has not developed a succession plan to confront this problem. Based on an analysis Laboratory Services performed, the average age of a Laboratory Services examiner in 2013 was roughly 61, with management‑level examiners having an average age of 65. We expected to find Laboratory Services had adopted a succession plan that would include identifying staff competency gaps, developing strategies to address those gaps, and identifying and developing the potential of current employees to fill key leadership positions. However, Laboratory Services’ management has not developed or implemented a succession plan. The assistant deputy director stated that Laboratory Services has handled succession planning by bringing back retired annuitants and that historically Laboratory Services has not developed staff through training to prepare them to move into senior positions. She also acknowledged that succession planning is important because a significant number of staff are eligible for retirement. She said she is currently drafting a reorganization plan that accounts for staffing and succession difficulties; however, the timing of that plan’s approval and implementation is uncertain. Although the assistant deputy director asserted she would like to start implementing her plan in October 2015, she noted that the plan hinges on approval from Public Health’s human resources branch and is dependent on previously lost positions being reestablished.

Laboratory Services Has Failed to Address Recommendations to Improve Its Information Technology Systems and Outdated Regulations

Laboratory Services has not updated or substantially improved its information technology systems to adequately support its activities. Table 3 summarizes the information systems issues we identified in 2008. When an information technology system contains illogical, incomplete, or incorrect data, its usefulness as a tool to aid management’s decision making is limited. Laboratory Services’ continued reliance on information technology systems containing flawed data shows that it has not taken steps to address the recommendations from our 2008 audit.

The information technology systems relevant to Laboratory Services include the Health Applications Licensing system (HAL), which is a legacy system that provides licensing information for labs. Although seven years have passed since our 2008 audit, Laboratory Services has not improved HAL in response to our audit recommendations. Public Health’s information technology services division provided us with a log of changes it made to HAL since 2008 in response to Laboratory Services’ requests, which included changes such as exporting a list of lab directors to a downloadable file rather than to a printer and making modifications to individual lab records. However, none of the changes addressed our recommendations. For example, in our 2008 audit, we found that the complaint field was limited to a yes or no indicator and that HAL’s lack of additional fields for information such as the nature or status of the complaint limited the system’s usefulness as a management tool. Nevertheless, the change logs do not reflect that Laboratory Services requested additional fields for recording complaint information in HAL.

Laboratory Services also uses four Microsoft Access databases to track complaints and sanctions. We found that the problematic conditions with these databases that we identified in our 2008 audit were generally unchanged, confirming that Laboratory Services has not responded to our recommendations. Specifically, we were unable to verify that many of the complaints appearing in the complaint logs were listed in the complaints database. Also, the sanction database did not include an ongoing sanction concerning a lab that employed unlicensed personnel to perform highly complex testing. In the most striking example, in 2013 Laboratory Services received more than 100 complaints according to its complaints logs, but none of these complaints were recorded in its complaint database for that year. Because it does not consistently track complaints in its database, Laboratory Services is forced to research how many complaints are open at any given time. Further, the paper complaint logs we reviewed did not consistently include information about the nature of the specific complaints received, thus making more difficult Laboratory Services’ task of prioritizing complaint investigations or evaluating the frequency and types of allegations against specific labs.

Laboratory Services does not have specific plans to upgrade the information technology systems relevant to its work, and the assistant deputy director could not provide a time frame for when Public Health might consider such plans. She explained that although Public Health wants to improve Laboratory Services’ information technology systems, it has not yet begun work on the necessary feasibility studies. She said that Public Health will not begin these studies until it completes another information technology system project, and she could not provide a date for that.

Laboratory Services has also not updated lab regulations since our prior audit, although we found that it has identified lab regulations that it needs to change. In our last report, we identified specific regulations that were not consistent with state law. For example, state regulations define unsuccessful participation in proficiency testing as three consecutive failures, while state law, as amended to adopt federal regulations, defines unsuccessful participation as two consecutive failures or two failures out of three consecutive tests. We expected to find that Laboratory Services had taken action to repeal outdated state regulations, thereby averting misunderstandings both within Laboratory Services and between it and the regulated community. Nonetheless, Laboratory Services has not taken action to change the regulations. An attorney with Public Health provided us a log she asserted Public Health uses to track its regulatory packages; the log reflects that Public Health plans to submit five regulations packages related to labs to the California Secretary of State from March 2016 through December 2019.

The State’s Oversight of Clinical Labs Largely Duplicates Efforts at the Federal Level, Raising Questions as to Whether a Separate State Approach Is Needed

With Laboratory Services’ history of failing to perform its oversight responsibilities, the State has, in effect, relied on CLIA to ensure that labs perform accurate testing. Even if Laboratory Services were fulfilling its mandates, the core requirements found in state law concerning the licensing and oversight of labs duplicate those found in CLIA. The duplication does not appear to provide any added benefit to California’s consumers, in part because Laboratory Services has historically been unable to manage its workload, as discussed earlier in this report, and in part because the requirements set out in CLIA and monitored by CMS represent a reasonable alternative to Laboratory Services’ failed oversight.

We therefore believe the Legislature should consider eliminating the requirement that the State license labs and instead rely on CLIA and the licensing and oversight structure CMS manages, as many other states do. We believe that eliminating the duplicate state requirements would have a negligible effect on the CLIA section’s workload because the bulk of its responsibility is inspecting and monitoring proficiency testing for CLIA‑certificated labs, and the number of these labs would not change.

As previously mentioned, Laboratory Services also currently issues and monitors licenses for personnel who work in labs to ensure they meet state requirements. We did not review Laboratory Services’ effectiveness at administering the state licensing requirements for lab personnel; therefore, we believe Laboratory Services should maintain this responsibility at this time.

The State Law That Specifies Lab Requirements Largely Duplicates CLIA

The state law that mandates Laboratory Services’ oversight of labs largely duplicates CLIA’s requirements. Given the significant similarities, along with Laboratory Services’ difficulty in completing its oversight responsibilities, we question the State’s need to maintain lab requirements separate from CLIA’s. The core state and federal requirements for licensing and oversight of labs are summarized in Table 4 and, as the table shows, the requirements in state law and CLIA are identical. For example, both state law and CLIA would require labs that conduct complex tests on specimens originating in California, to be authorized to perform tests and to pay fees for oversight. Both state law and CLIA would also require that labs receive ongoing, periodic oversight composed of biennial inspections and monitoring of their proficiency‑testing results. Finally, both state law and CLIA provide for complaint investigations and sanctions of labs as needed to ensure that they correct any deficiencies.

Table 4

A Comparison of the Core Requirements in State Law and the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988

| CORE REQUIREMENT | STATE LAW | CLINICAL LABORATORY IMPROVEMENT AMENDMENTS OF 1988 (CLIA) |

|---|---|---|

| All clinical laboratories (labs) must be authorized to analyze specimens.* | ✓ | ✓ |

| All labs must pay a fee for initial authorization and then periodically to renew.† | ✓ | ✓ |

| Labs must be inspected biennially.‡ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Labs must enroll and successfully participate in proficiency testing.‡ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Complaints against labs are investigated, which may include on-site inspections.‡ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Labs may be sanctioned for failing to meet requirements.‡ | ✓ | ✓ |

Sources: California Business and Professions Code; Title 42, Code of Federal Regulations, Section 493; and auditor analysis of state and federal law.

* State law requires labs to either register or obtain licenses depending on the types of tests they perform. CLIA requires labs to apply for one of

several certificates depending on the types of tests they perform.

† State law requires labs to renew their licenses or registrations annually. CLIA requires labs to apply for new certificates biennially.

‡ Labs performing moderately complex to highly complex tests are subject to biennial inspections and proficiency testing. Labs performing simple

tests are not subject to these two requirements. However, all labs are subject to complaint investigations and sanctions.

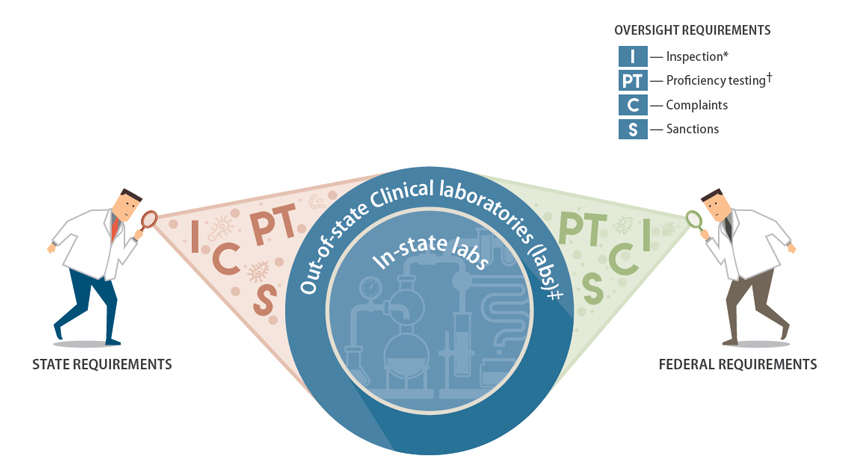

Lab requirements and the oversight embodied in state law reach beyond California’s borders when out‑of‑state labs test samples originating from within the State. Thus, labs in other states and countries must obtain licenses or registrations from Laboratory Services if they test specimens from California. CLIA applies to labs in a similarly broad manner; all labs, including those in other countries, that test specimens collected in the United States and its territories are subject to CLIA. Therefore, as Figure 6 shows, all labs analyzing specimens originating in California are subject to state law and to CLIA. For example, a lab operating in Michigan that performs complex tests on samples originating in California would be subject to Laboratory Services’ biennial inspections, proficiency testing, and oversight, and it would also be bound to the requirements found in CLIA as monitored and enforced by CMS and its agents.

Figure 6

Redundancy Between State and Federal Oversight Requirements for Clinical Laboratory Facilities

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of state law and federal regulations.

* Labs performing moderate to high complexity tests—tests with a higher chance of risk or error such as hepatitis testing—are subject to state oversight

inspections no less than once every two years. In contrast, state law exempts registered labs—those performing simpler tests with less chance of error

such as prepackaged manufactured tests—from routine inspections, but the State is authorized to inspect them at any time it sees fit.

† Proficiency testing is the external evaluation of the accuracy of a lab’s test results. Only labs performing moderate to high complexity tests are subject

to proficiency testing under state law and federal regulation.

‡ For state purposes, out-of-state labs are those labs located outside of California that test specimens originating from within California. These labs are

subject to both California’s lab facility requirements and federal requirements.

Under CLIA, states are allowed to develop their own licensing programs and requirements that are more stringent than federal standards. Once it adopts such requirements, a state can request that CMS exempt it from CLIA’s requirements and thus retain full oversight over the labs within its jurisdiction. Currently, only two states—Washington and New York—are exempt from some or all of CLIA’s requirements. In the mid‑1990s, California considered applying for its own CLIA exemption. The Legislature passed Senate Bill 113 (Chapter 510, Statutes of 1995) to make several changes to state law in an attempt to incorporate CLIA’s standards while enacting more stringent standards for lab personnel, thus placing the State in a position to seek CLIA exemption. According to a report Laboratory Services prepared, the State earned CLIA exemption in 1999 but subsequently declined it because of concerns with paying an overhead fee—$2.4 million per year—to the federal Department of Health and Human Services. As a result, the State has been operating under a largely duplicate set of state and federal standards ever since.

CLIA Is a Reasonable Alternative to Laboratory Services’ Ineffective Oversight of Labs

Given Laboratory Services’ performance and management problems and the duplicate oversight structures that exist under state law and CLIA, it does not appear to us that California’s consumers receive meaningful protections from Laboratory Services’ oversight of labs. If the Legislature desires to eliminate the inefficient duplication, it could repeal state law requiring that labs obtain state licenses or registrations while leaving in place the State’s more stringent requirements governing lab personnel. In fact, most states do not have their own lab licensing programs and rely instead on the oversight structure that CMS administers. Based on an analysis an accreditation organization prepared, about 30 states—or just over 60 percent—did not have state lab‑licensing and oversight programs as of June 2014. In particular, some states with large populations—such as Texas and Michigan—do not issue state licenses to labs and instead work with CMS to enforce CLIA requirements. As a result, these states rely solely on CLIA oversight and the related monitoring and enforcement that CMS and its state agents provide.

CMS’s oversight process focuses on clinical labs being inspected and monitored by its state agents or accreditation organizations, while it monitors the oversight work these groups provide. As described in the Introduction, Laboratory Services acts as CMS’s state agent in California and has established a specific unit—the CLIA section—to provide oversight. According to CMS data, as of July 2015 the CLIA section oversaw 1,550 CLIA‑certificated labs that performed moderately to highly complex tests.2 CMS uses a variety of means to help ensure that the CLIA section fulfills its oversight role. For example, CMS annually contracts with Laboratory Services and provides funding for CLIA section staff to participate in mandatory training. CMS also assesses the CLIA section’s performance through monitoring surveys that evaluate examiners’ performances while inspecting particular labs. The purpose of these monitoring efforts is to alert CMS if Laboratory Services’ staff require further training or other feedback as they monitor labs on behalf of CMS.

CMS also annually assesses the CLIA section through comprehensive performance evaluations. The CLIA section’s last two performance evaluations documented that it had met CMS’s expectations and developed and adhered to corrective action plans as necessary. Specifically, for the most recent evaluation in 2015, CMS commended the CLIA section for its fine performance because it exceeded CMS’s expectations for all criteria reviewed; consequently, no corrective action plan was necessary. The evaluation documented the CLIA section’s historical performance for certain oversight responsibilities and noted that since 2007 the CLIA section has earned perfect scores related to its proficiency testing process and complaints process. The CLIA section’s May 2014 performance evaluation showed that it was responsive to CMS, which had identified two labs during the prior year’s evaluation that it had not inspected in a timely manner. In response, the CLIA section developed a written corrective action plan detailing how it would ensure that it identified for inspection labs with expiring certificates, and CMS did not identify this issue in the CLIA section’s following year’s performance evaluation.

CMS also takes steps to ensure that accreditation organizations maintain strict standards and fulfill their federal oversight role. In California, accreditation organizations oversaw 1,236 labs as of July 2015, according to CMS’s data. To become an authorized accreditation organization, an entity must provide CMS with a detailed comparison of its requirements and CLIA’s requirements and must describe its inspection process, its process for monitoring proficiency testing, and its process for responding to complaints. At least every six years, an accreditation organization must reapply to CMS to maintain its status as an authorized accreditation organization. In between application reviews, CMS requires its state agents to oversee the accreditation organizations by annually evaluating a subset of their lab inspection results; CMS may also conduct on‑site inspections. For example, a state agent on CMS’s behalf will reinspect a lab following an accreditation organization’s inspection in order to compare inspection results; in California, the CLIA section performs these reviews on CMS’s behalf. If the state agent’s review shows substantial disparities from the expected results, CMS may terminate the accreditation organization’s ability to act as its agent.

As discussed in the Introduction, the director and assistant director from the Office of the State Public Health Laboratory Director oversee Laboratory Services. When we asked for their perspective on phasing out certain Laboratory Services mandates, they acknowledged that they have considered changes to Laboratory Services’ responsibilities, such as seeking to end the State’s licensing of labs in favor of following a CLIA‑only model. However, the assistant director stated that they had concerns about the effect on Laboratory Services’ personnel licensing mandates if the Legislature eliminated its lab‑licensing mandates. According to the director, the ability to inspect labs has given Laboratory Services a venue to enforce its personnel licensing requirements, but he acknowledged that Laboratory Services may simply need clear authority to enter facilities for personnel licensing enforcement. Ensuring that professionals have adequate training and experience to qualify them for laboratory positions is a valuable safeguard. Our proposal to eliminate lab‑licensing and oversight requirements does not extend to personnel licensing requirements. We did not review Laboratory Services’ effectiveness at administrating personnel licensing; therefore, at this time, it is our intention that those requirements be maintained.

Although the State has historically maintained lab requirements separate from CLIA, we believe that eliminating the duplicate requirements will have a negligible effect on the CLIA section’s workload. Most of the CLIA section’s current responsibilities will remain the same if the State discontinues its lab requirements. The CLIA section would continue to inspect nonaccredited labs, its current responsibility. In contrast, Laboratory Services would cease to monitor accredited labs for compliance with state law; however, these accredited labs would continue to be monitored by their accreditation organizations and would still be subject to review by CMS or its agents in response to substantial allegations of noncompliance with federal requirements. The CLIA section’s focus would be CLIA‑certificated labs; accredited labs would be overseen by the accreditation organization. The CLIA section might become responsible for additional complaints and sanctions if the State discontinues its lab requirements because complainants would no longer be able to file complaints with Laboratory Services. Thus, complainants who in the past might have filed complaints with Laboratory Services would need to file them with either the CLIA section or the accreditation organizations, depending on the labs’ authorization. For example, based on Laboratory Services’ pattern of assigning complaints for investigation, we determined that 69 of the 218 complaints Laboratory Services received between January 2014 and April 2015 might have required the CLIA section’s attention.

When we spoke with the CLIA section chief (CLIA chief), she indicated that California could become a CLIA‑only state with minimal to no effect on the CLIA section’s workload. The CLIA chief noted that in the absence of a state‑licensing requirement for labs, some complaints could be filed with her section. The CLIA chief clarified that under CLIA rules, CMS would direct complaints alleged against an accredited lab to the accreditation organization, but at times it might involve the CLIA section. The CLIA chief also shared that complaints that rise to the level of sanctions would require the CLIA section to prepare sanction proposals for CMS’s consideration. However, the CLIA chief confirmed that the CLIA section’s workload associated with inspections and proficiency‑test monitoring would not change.

Employing accreditation organizations as oversight partners is a strategy CMS uses at the federal level, and the Legislature has long recognized the valuable role accreditation organizations can play in state oversight. With the passage of Senate Bill 744 (SB 744) (Chapter 201, Statutes of 2009), the Legislature provided for an application process whereby accreditation organizations, if approved by Laboratory Services, would have their accredited labs deemed as meeting the State’s requirements. Under this framework, the Legislature required that accreditation organizations inspect their member labs and monitor their proficiency testing in lieu of Laboratory Services performing these oversight duties. Although the Legislature maintained Laboratory Services’ authority to investigate complaints against accredited labs—which under federal rules is a responsibility left to the accreditation organizations—the oversight model the Legislature envisioned in SB 744 places several of the core oversight responsibilities over clinical labs, such as performing inspections and monitoring the results of proficiency testing, in the hands of accreditation organizations.

Even though state and CLIA lab requirements are mostly the same, state law includes a few requirements that are not found in CLIA. One such requirement is that the lab owners must be disclosed on the State’s lab application; if the Legislature eliminates the requirement that labs obtain state licensure or registration, then the State would no longer have that information. According to the facility section chief of the Richmond branch, Laboratory Services uses owner information, for example, to ensure that owners who have operated labs whose licenses have been revoked or that have received sanctions cannot own or operate labs for two years. She also stated that CMS sometimes requests lab ownership information because the federal government does not track this information. However, we found that CMS and its agents obtain ownership information in different ways. For example, federal law requires that a lab owner or an authorized representative sign the CLIA certificate application and report any ownership change within 30 days after it occurs. Moreover, the CLIA certificate application requires the applicant to report his or her federal tax identification number, which could be used to obtain information about lab ownership. Finally, federal law also states that no person who has owned or operated a lab that has had its certificate revoked may, within two years, own or operate a lab operating under CLIA; to help enforce this law, CMS publishes an annual report on labs and persons who have violated CLIA requirements.

Another unique state requirement is that labs must conspicuously post their state licenses in their lab facilities; however, if the State no longer issues licenses, this requirement becomes moot. The facility section chief said she believes posting the license is for the public’s benefit because it promotes transparency and includes information that allows customers to know the lab is legitimate. However, we believe the Legislature could, for example, easily require that labs post their CMS‑issued certificates to continue to promote public transparency. As a result, California’s unique state requirements should not pose a barrier to transitioning to a CLIA‑only model.

Recommendations

Legislature

To eliminate the State’s redundant and ineffective oversight of labs and to ensure labs do not pay unnecessary or duplicative fees, the Legislature should do the following:

- Repeal existing state law requiring that labs be licensed or registered by Laboratory Services and that Laboratory Services perform oversight of these labs. Instead, the State should rely on the oversight CMS provides.

- Repeal existing state law requiring labs to pay fees for state‑issued licenses or registrations.

If the Legislature decides to continue requiring that clinical labs be licensed or registered through the State, it should amend state law establishing how Laboratory Services annually adjusts its fee amounts to ensure the revenue it collects does not exceed the cost of its oversight. Such an amendment might authorize Public Health to temporarily suspend or reduce fees when the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Fund’s ending balance exceeds a prudent reserve amount that the Legislature establishes.

Regardless of whether it decides to repeal existing law, the Legislature should direct Laboratory Services to advise it on how best to address the millions of dollars in the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Fund in excess of a prudent reserve.

Laboratory Services

While the Legislature considers eliminating the requirement that labs obtain state‑issued licenses or registrations and receive oversight from Laboratory Services, Laboratory Services should begin taking action to address its deficiencies by developing a corrective action plan by December 31, 2015. The corrective action plan should address its plans for implementing the recommendations from our 2008 audit and from this follow‑up audit. For each item in its corrective action plan, Laboratory Services should identify the individuals responsible for ensuring it takes the corrective action, the resources it needs to carry out the corrective action, and the time frame in which it expects to successfully complete the corrective action.

To ensure it can provide effective oversight of labs as state law requires, Laboratory Services should do the following:

- Every two years, inspect all in‑state and out‑of‑state labs it has licensed.

- Develop and implement proficiency testing policy and procedures for ensuring that it can promptly identify out‑of‑state labs that fail proficiency testing.

- Improve its complaints policy and procedures to ensure that it either investigates allegations promptly or clearly documents its management’s rationale for not investigating. It should also establish clear expectations for when staff must visit a lab to verify successful corrective action.

- Dedicate multiple staff to sanctioning efforts and update its sanctioning policy and procedures, including identifying steps to ensure that labs adhere to sanctions and that it collect civil money penalties. In addition, it should develop a single sanctions tracking system that multiple managers can monitor and that will allow it to periodically reconcile the monetary penalties it receives with Public Health’s accounting records.