Introduction

Background

To protect air quality across the country and to promote public health and welfare, Congress enacted the federal Clean Air Act, which regulates air emissions from stationary sources, including factories and chemical plants, and mobile sources, such as motor vehicles. To implement the law, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) sets air quality standards for various air pollutants, establishing levels so as to protect public health and welfare. For each air quality standard, the U.S. EPA also designates geographic regions as either attainment areas, which are at or below the level established by the U.S. EPA for that pollutant, or as nonattainment areas, which are above the established level for the pollutant.

To achieve the goals of the federal Clean Air Act, the U.S. EPA works with the states, including California, under a cooperative model. States have primary responsibility for assuring air quality within their respective boundaries and must develop a state implementation plan that specifies how the state will meet and maintain air quality standards. In California, the California Air Resources Board regulates the air pollution caused by motor vehicles, and the local air quality control districts regulate the air pollution caused primarily by stationary sources—large, fixed sources of air pollution, including power plants, refineries, and factories. The San Joaquin Valley Unified Air Pollution Control District (district) adopts rules designed to meet the air quality standards set by the U.S. EPA for the San Joaquin Valley related to stationary sources of pollution.1

The district began operating in March 1991 and was formed through the merger of existing county districts covering eight counties: San Joaquin, Stanislaus, Merced, Madera, Fresno, Kings, Tulare, and part of Kern. Figure 1 below shows the boundaries of the district. State law requires that the district be governed by a 15-member board, including one member appointed by each county’s board of supervisors; one medical or science professional and one physician, each appointed by the governor; and five city council members from cities within the district. These city council members are appointed by a special city selection committee consisting of one city council member from each city located within the district’s territory. A majority of members on each city council chooses the member who will sit on the special city selection committee.

Figure 1

Boundaries of the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District

Source: San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District.

The San Joaquin Valley’s climate, transportation infrastructure, industrial demographics, and geography make it highly susceptible to air pollution. In fact, the district has been designated by the U.S. EPA as a nonattainment area since the early 1990s, and it is currently designated as a nonattainment area for certain types of pollution, meaning its levels exceed the established levels for those pollutants. The district comprises the entire San Joaquin Valley Air Basin, which is approximately 250 miles long, stretching from Stockton to Bakersfield, and which is bordered on three sides by mountain ranges that capture air pollution. Pollution in the San Joaquin Valley comes from numerous sources, including 4 million residents who live in the valley and their vehicles. The San Joaquin Valley also contains two prominent highways: Interstate 5 and State Route 99. In addition, a number of stationary sources of air pollution affect air quality in the district. According to the U.S. EPA, the San Joaquin Valley is California’s top agricultural producing region, growing more than 250 unique crops. Further, the U.S. Department of Agriculture reports that California has the most dairy cows of any state in the nation, and 89 percent of the State’s dairy cows live in the San Joaquin Valley. These agricultural activities create dust and other air pollutants that the district regulates. Another source of air pollution in the valley is oil and gas production from refineries. All of these factors combined have made the counties within the district among the most polluted the U.S. EPA has measured nationally for small particle pollution, as can be seen in Figure 2 below. Small particle pollution consists of particles found in the air, such as dirt, dust, soot, smoke, and liquid droplets, that are less than 2.5 micrometers and small enough to lodge deeply in the lungs. High levels of air pollution, specifically ozone and particle pollution, threaten the health and lives of those who live in such areas by causing respiratory and cardiovascular problems—including asthma, heart attacks, and strokes—and particle pollution may also cause cancer.

Figure 2

The Most Polluted Counties for Small Particle Pollution

Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (U.S. EPA) PM2.5 county-level summary for annual design values for 2012 through 2014. PM2.5 pollution is small particles found in the air, such as dirt, dust, soot, smoke, and liquid droplets, that are less than 2.5 micrometers in size.

Note: Counties identified in red are seven of the eight counties that constitute the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District. Merced, the eighth county, was the 21st most polluted county for PM2.5 levels. Stanislaus and San Joaquin had the same annual PM2.5 level. The ranking includes 470 counties nationally for which the U.S. EPA calculated values based on county-reported data that met certain mandatory requirements for 2012 through 2014. Counties that did not submit information or that submitted incomplete information are not included in the ranking.

District Permitting Fees and Revenue

The federal Clean Air Act requires each state to establish a stationary source permitting system (permitting system). In addition, California law authorizes every air pollution control district to establish a permitting system that requires every person who operates a stationary source of air contaminants to obtain a permit from the district. To implement its permitting system, the district has adopted rules that impose certain requirements on various activities that result in stationary source pollution, and it charges fees for issuing permits and conducting related regulatory activities. These permits include permits covering the construction and operation of certain types of pollution-causing equipment. The district may combine the fees it receives from these permits and use the funds to cover the costs of district programs related to permitted stationary sources of pollution.

Under its permitting system, the district also charges other program fees. These other program fees—which we refer to as special program fees—are for specific programmatic purposes. For example, it charges a special program fee for those who register portable emissions-generating equipment. According to the proposal establishing the fee, this fee is to cover the cost of administering the portable equipment registration program. The district also regulates certain other “nontraditional” stationary sources of pollution, such as asbestos removal and wood-burning heaters, and it charges special program fees to cover the costs of regulating those specific activities. In addition, the district charges certain other fees, which we refer to as in-lieu-of-compliance fees because fee payers may pay these fees to avoid complying with a pollution reduction rule or to be able to comply with a less strict requirement. The district must use the revenue it obtains from these in-lieu-of-compliance fees to support pollution reduction activities related to the same types of pollution the rule seeks to reduce. For fiscal years 2010–11 through 2014–15, the district received annual average revenue of $5.9 million from one of its in-lieu-of-compliance fees, the Advanced Emissions Reduction Option. For two of these years, the district also received a small amount from another in-lieu-of-compliance fee, the Internal Combustion Engine Option. According to a deputy air pollution control officer, the district has spent this revenue on projects aimed at advancing emission reduction technology and on various emissions reduction projects funded by the district’s grant components. Examples of the fees charged appear in the Appendix.

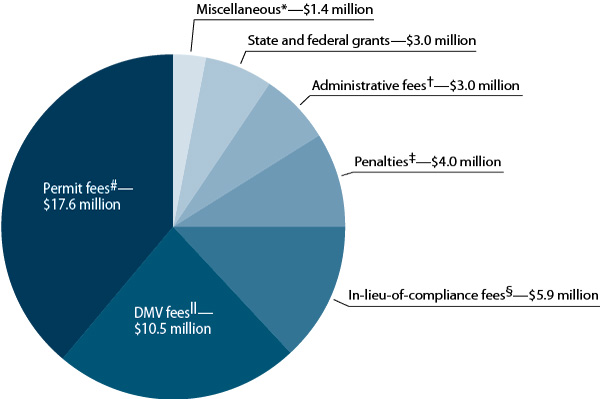

From fiscal year 2010–11 through 2014–15, the district’s annual operating revenue averaged more than $45.4 million, which includes revenue for its permitting activities as well as other district functions. As shown in Figure 3, the district’s annual revenue from its permit fees, on average, was $17.6 million for the same period.

Figure 3

Average Annual Operating Revenue Sources for the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District

Fiscal Years 2010–11 Through 2014–15

Sources: Accounting system and comprehensive annual financial reports for fiscal years 2010–11 through 2014–15 for the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District (district).

* Miscellaneous revenue includes sources such as interest earned.

† According to the district’s director of incentives and administrative services, administrative fees are portions of grant funds received by the district designated to cover its costs to administer the grants.

‡ Penalties include revenue from charges relating to noncompliance with district rules. The district refers to these penalties as settlements.

§ In-lieu-of-compliance fees is our term for the four fees that can be paid in lieu of complying with an emissions limit.

ll State law allows the district to receive fees collected from motor vehicle registrations to use to reduce air pollution from motor vehicles and for related planning, monitoring, enforcement, and technical studies necessary for the implementation of the California Clean Air Act of 1988. These fees cannot be used to support the district’s stationary source permitting system.

# Permit fee revenue includes revenue from construction, annual operating, and special program fees.

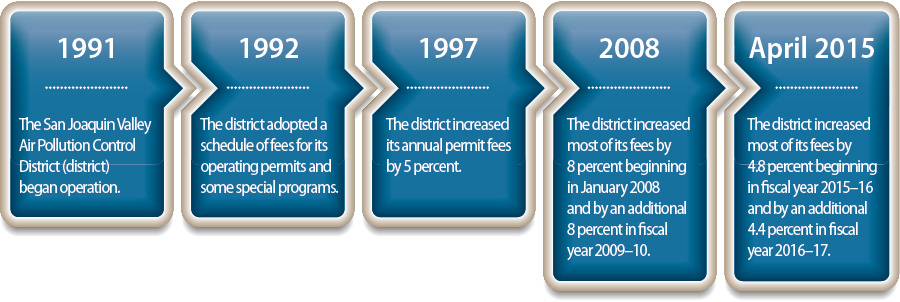

Since establishing its initial schedule of fees in 1992, the district has uniformly increased the majority of its fees three times: in 1997, 2008, and 2015. As shown in Figure 4, in 1997 the district increased its fees by 5 percent; in 2008, it instituted a two-part increase of 8 percent in fiscal year 2008–09 and another 8 percent increase in 2009–10; and in 2015, it instituted another two-part increase of 4.8 percent in fiscal year 2015–16 and an additional 4.4 percent in fiscal year 2016–17. The district has also amended individual rules governing air pollution to add fees. For example, the district amended a rule in January 2015 to add the option of paying a fee in lieu of compliance with a stricter emissions limit on heaters. Sellers of heaters would either have to sell only units that comply with the new limit or pay the district a fee per noncompliant unit sold.

Figure 4

Time Line of the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District’s Creation and Fee Increases

Sources: District’s consolidated annual financial reports, minutes from the district’s governing board meetings, and staff reports to the district’s governing board.

Scope and Methodology

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee directed the California State Auditor to perform an audit to determine the sufficiency of revenue from stationary sources of air pollution and permit fees and to assess whether the district’s policies require certain entities to post bonds against potential lawsuits. Table 1 lists the audit objectives and the methods we used to address them.

| Audit Objective | Method | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Review and evaluate the laws, rules, and regulations significant to the audit objectives. | Reviewed relevant laws, regulations, and other background materials applicable to the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District (district). |

| 2 | Determine whether the district’s revenue from stationary sources and permit fees are sufficient to fund selected industries’ permitting and regulation programs including, but not limited to, the following: | |

| a. Review district policies and methodologies for setting fee rates. |

|

|

| b. Assess whether the fees are reasonable and allowable. Review revenue, expenditures, and fund balances of fee-based programs over the past five fiscal years. |

|

|

| c. Assess if the district is supplementing certain programs with funds from other fee-based programs or other state and federal fund sources. |

|

|

| 3 | Determine whether the district’s policies require certain entities to post bonds against potential lawsuits resulting from the district’s granting of permits including, but not limited to, the following: | |

| a. Review district methodologies for establishing bonding policies and assess whether they are reasonable. |

|

|

| b. Assess which types of permits meet the bonding requirement set by the district. |

|

|

| c. Determine whether the district budgets for litigation costs resulting from contested permits. If it does, assess the reasonableness of the funding amount and any relationship the funding may have to entities required to post bonds. |

|

|

| 4 | Review and assess any other issues that are significant to the audit. | We did not note any other significant issues. |

Sources: California State Auditor's analysis of Joint Legislative Audit Committee audit request number 2015-125, and information and documentation identified in the table column titled Method.

Assessment of Data Reliability

The U.S. Government Accountability Office, whose standards we are statutorily required to follow, requires us to assess the sufficiency and appropriateness of computer-processed information that we use to support our findings, conclusions, or recommendations. In performing this audit, we obtained electronic data files extracted from the district’s Serenic Navigator system for July 1, 2010, through June 30, 2015. We did not perform accuracy and completeness testing on these data because the district’s Serenic Navigator system is a mostly paperless system. Alternatively, we could have reviewed the adequacy of selected information system controls but determined that this level of review was cost-prohibitive. However, to gain some assurance of the reliability of the data for revenue by fee category and expenditures by division, we compared Serenic Navigator information to the district’s audited financial statements and found that the data were consistent with reported financial information. As a result, we assessed the data as being of undetermined reliability for the purpose of calculating the district’s revenue and expenditures. Although this determination may affect the precision of the numbers we present, we found sufficient evidence in total to support our findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

Footnote

1Although the district’s official name includes Unified, it typically uses its more common name—the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District. Therefore, throughout this report, we use its common name. Go back to text