Audit Results

The San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District’s Permit Fee Revenue Is Below Its Costs, and It Supplements This Revenue With Other Sources of Funding

The stationary source permit fees (permit fees) charged by the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District (district) are allowable and generate fee revenue less than the district’s costs. As described in the Introduction, the district operates a stationary source permitting system (permitting system) for which it charges fees for the permits it issues. The district initially established its permit fees in 1992. State law allows the district to adopt, by regulation, a schedule of annual fees to cover the cost of district programs related to permitted stationary sources. The district may not collect fees in excess of the associated costs.

To help determine the costs associated with the various fees, the district has established a process for staff to charge their time to activities relating to specific fee rules, which are district regulations implementing its various programs. Our review found that the activities to which district staff charged their time related reasonably to the fees charged. For example, district staff charged time to the agricultural burning fee for activities such as preparing inspections and processing permits relating to agricultural burning. The district used the hours staff charged to estimate the expenditures relating to each fee rule. For its most recent fee increase, the district calculated the costs associated with each fee by using a percentage based on the number of hours that each division charged to a particular fee compared to the total expenditures for that division. For example, in fiscal year 2013–14, staff in the district’s permitting division spent 339 hours on activities related to the certified air permitting professional fee, and the district assigned a proportional share of expenditures, nearly $45,000, to that fee. Following the district’s method, we found that none of the revenue for a particular fee exceeded the regulatory costs associated with that fee.

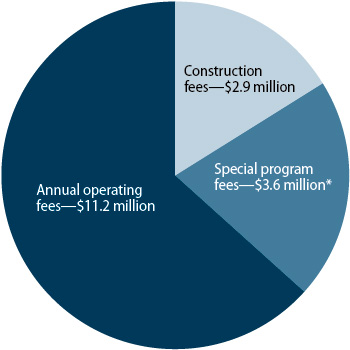

The district’s fee revenue covers only a portion of the costs of its permitting system. As noted in Figure 3 earlier in the report, an average of $17.6 million, or 39 percent of the district’s annual average operating revenue for fiscal years 2010–11 through 2014–15, came from its permit fees. This revenue consists of revenue from the district’s construction, annual operating, and special program fees, as shown in Figure 5 below. However, this revenue has not been sufficient to cover the regulatory costs of the inspection and review activities for any of the district’s programs for which it charges fees. Specifically, when the district analyzed its permitting system revenue and expenditures for fiscal year 2013–14 in connection with its most recent fee increase, it found that each fee’s revenue was less than the fee’s associated regulatory cost.

Figure 5

Average Annual Permit System Revenue Sources for the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District

Fiscal Years 2010–11 Through 2014–15

Source: Accounting system for the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District.

Note: The average annual permit fee revenue sources total is $17.7 million, which is slightly higher than the amount shown in Figure 3. The differences are due to rounding.

* Revenue for select special program fees is broken out in Figure 6.

The district also has other sources of revenue that it uses to supplement its permit fee revenue, including revenue from penalties, interest earned, and state and federal grants. The legal restrictions for the penalty revenue and the state and federal grants allow these amounts to be used to supplement the permitting system. For fiscal years 2010–11 through 2014–15, the district received an average of $8.3 million annually from these other sources of revenue. Although the district identifies total supplemental revenue in its financial statements, the district does not typically distinguish how much revenue from other sources it uses to supplement its permitting system versus how much it uses for other functions. However, when calculating its most recent fee increase, it identified approximately $4.9 million in supplementary revenue in fiscal year 2013–14 that it allocated specifically for its permitting system.

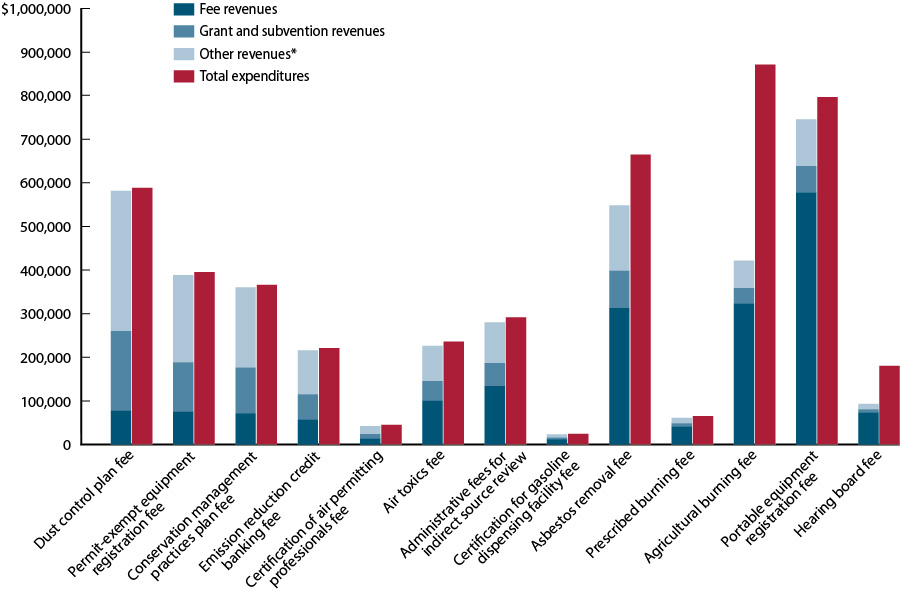

The district’s director of incentives and administrative services stated that, in calculating the recent fee increase, the district allocated this $4.9 million in supplementary revenue to the various fee rules in proportion to the district’s expenditures related to each fee rule. She also stated that expenditures for each rule can fluctuate annually based on the demands of each permit or program. Therefore, according to this director, the district used its discretion to adjust the allocation of the other revenue amounts among the rules to keep the fees for each rule stable year to year. For example, the district increased the amount of supplemental funding assigned to its dust control plan fee rule, noting costs were well above average in fiscal year 2013–14 because of conditions caused by the drought. As a result of these calculations, the district assigned each fee rule a different percentage of the supplementary funding. After this allocation, each fee’s total revenue was still less than the associated expenditures, as shown for select special program fees in Figure 6. The district also had an unassigned fund balance in its general fund, which it drew on in fiscal years 2012–13 and 2013–14. As of June 2014, the fund balance was $13.3 million. Although the district needed to use less of its unassigned fund balance than it budgeted in fiscal years 2012–13 and 2013–14, it projected that it would continue to draw from its fund balance in the future. Budgeted use of its fund balance is one criterion the district considered when analyzing the need for a fee increase. From fiscal year 2010–11 through 2013–14, the district maintained an unassigned fund balance in its general fund of between $13.1 and $14.3 million, which is equivalent to roughly three months of operating expenses.

Figure 6

Select Special Program Fee Revenue and Related Expenditures for the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District

Fiscal Year 2013–14

Source: San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District (district) fee review completed in 2015.

Note: The above fees include all special program fees for which the district analyzed revenue and expenditures for its most recent fee increase. It does not include the federally mandated ozone nonattainment fee, which is set in the federal Clean Air Act, and the Regulation VII alternative compliance plan review fee, as the district did not collect any revenue for the fee in fiscal year 2013–14.

* Other revenues include amounts from interest and penalties from noncompliance with district rules.

As part of the district’s annual budget process, it considers whether current revenue is adequate to cover costs. If not, the district may pursue a fee increase. During its budget process, the district projects the workload associated with its tasks and functions, and then it calculates the associated labor costs, including its indirect costs. In addition, the district develops five year revenue projections for each of its fee based rules. According to the director of incentives and administrative services, the district then determines whether the revenue other than fees, such as funding from grants and penalties as well as unassigned fund balances, are adequate to balance its budget. If the budget analysis indicates that the district will have insufficient total funds even after implementing feasible cost cutting measures and after reviewing the need for discretionary tasks, the district will consider increasing its fees.

According to a deputy air pollution control officer, based on its annual budget analysis in 2013 and other financial information, the district informed the governing board (board) that a fee increase might be necessary. At that time, the district projected that its operating revenue would be approximately $2 million short of its expenses for fiscal year 2014–15. In September 2013, the board approved a review of a potential fee increase. The district later submitted a proposal to amend the district’s fee rules, which the board adopted in April 2015. This amendment increased the majority of the district’s permitting program fees by 4.8 percent beginning on July 1, 2015, and by an additional 4.4 percent beginning on July 1, 2016.

In addition, according to the board’s meeting agenda item for the proposal, the district adjusted three particular fees to ensure adequate cost recovery and to avoid circumstances in which some businesses subsidized costs for others. Specifically, the district increased its hearing board fees by the same percentage as it had increased the other fees, but it also added an excess emissions fee for certain applicants. The district’s March 2015 staff report noted that certain applicants require additional staff time because of the size of the variance from district rules they are requesting from the hearing board. A variance is a temporary order allowing an entity to continue operations while it comes into compliance with district rules. To recoup some of these additional costs, the district imposed a new fee for variances with excess emissions. The district also changed its agricultural burning fee to $36 per burn site. Previously, the district had charged a permit fee amount based on the number of burn locations—one site, two sites, or three or more sites. Therefore, before the change in the fee’s structure, a small farmer with three burn sites would pay the same fee as a large operation with 100 burn sites. Finally, the district increased its asbestos removal fee by 37 percent for fiscal year 2015–16. A district deputy air pollution control officer indicated that the district raised this fee because regulating asbestos removals consistently costs the district more than the revenue generated by the fee and because the asbestos removal fee is a stand alone fee with a narrow scope of functions performed by the district.

Before the fee increase was approved in April 2015, the district had increased the majority of the permit fees by the same percentage (across the board) only two other times—in 1997 and 2008. In its most recent fee increase proposal, the staff report states that the district had minimized its need for across the board fee increases by adhering to fiscally conservative principles aimed at maximizing efficiency and minimizing costs, such as leveraging technology and streamlining processes to reduce related operating costs. Using the district’s fiscal year 2013–14 fee revenue, we estimated that the district’s permitting system fee revenue will continue to be 15 percent to 86 percent below the costs of the respective regulatory activities after its most recent fee increase takes full effect in fiscal year 2016–17. Therefore, the district will still need to make use of a portion of the other revenue it receives from penalties, interest earned, and state and federal grants to supplement its permit fee revenue. The district projected that with the fee increases and continued operational streamlining it will be able to balance its costs and revenue.

The District Can Improve the Consistency and Transparency of Its Process for Requiring Additional Financial Security and Indemnification From Permit Applicants

To protect the district and its many regulated customers from the potential costs of litigation, each year the district identifies projects that it considers a litigation risk and requires the permit applicants to sign an indemnification agreement and provide a letter of credit. The district issued an annual average of more than 4,600 Authority to Construct permits (construction permits) for fiscal years 2010–11 through 2014–15, and it has required fewer than 15 indemnification agreements and only 10 letters of credit on average for the last 5 fiscal years. An indemnification agreement is an agreement limiting the district’s financial liability and has no immediate financial cost. A letter of credit is issued by a bank that agrees to provide prompt payment on behalf of the permit applicant, if needed, unlike a bond, which may be subject to substantial delays when the district attempts to collect. The applicant generally must pay a charge to its bank for the letter of credit. If the district draws on a letter of credit, the bank then seeks payment from the applicant.

The indemnification agreements and letters of credit that the district requires are intended to mitigate the potential costs of litigation under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). California enacted CEQA in 1970, and it is an essential component of the district’s permitting process. According to state regulations, two of the basic purposes of CEQA are to inform individuals about potential, significant environmental effects of proposed activities and to identify ways that environmental damage can be avoided, significantly reduced, or mitigated. Further, state regulations require public agencies to disclose why the agencies approved projects if they involve significant environmental effects. Under CEQA, a resident can bring a lawsuit if he or she believes a project did not adequately mitigate the pollution it caused.

The district’s decisions as to which projects require indemnification agreements and letters of credit are informed by the role played by the district under CEQA. Specifically, CEQA and its guidelines define an agency’s role in the permitting process as that of either the lead agency or a responsible agency. The lead agency has principal responsibility for carrying out or approving a project that may have a significant effect upon the environment. According to state regulations, the lead agency on a project likely to have various environmental impacts that require approvals will normally be the agency with a general governmental purpose, such as a city or county, rather than an agency with a single or limited purpose, such as an air pollution control district. An entity that has some responsibility in the environmental approval process but that is not the lead agency is deemed a responsible agency. For example, according to the district counsel, when a dairy increases its herd, the district is most often a responsible agency because it has the single purpose of air quality management. However, air quality is just one among various environmental concerns that the project could potentially affect; these concerns include water quality, waste management, habitat conservation, and community conservation, which are outside the district’s purview. CEQA regulations also include guidelines for another category the district uses in deciding whether to require an indemnification agreement: whether the proposed project may have a “significant” effect on the environment.

The district’s CEQA implementation policy for construction permits, approved by district staff in 2010 and in place during our review, clearly states that when the district is the lead agency, it must require both an indemnification agreement and a letter of credit. The policy also states that when the district acts as a responsible agency for CEQA purposes, it may require an indemnification agreement. However, the district’s guidance to staff—which includes a procedural memo and a decision matrix (internal methodology)—for generally identifying which projects require an indemnification agreement or letter of credit provides some inconsistent guidance to staff. As shown in Table 2, the district developed a matrix to help staff identify projects that require additional security through an indemnification agreement and a letter of credit. The matrix indicates that district staff should consider whether or not the permit application is a subject of public concern. In its procedural memo, the district identifies specific areas that it considers to be of public concern. Despite the fact that the district’s published policy clearly requires both an indemnification agreement and a letter of credit when the district acts as the lead agency in an authority to construct situation, according to the matrix, district staff would not ask for a letter of credit if the district is the lead agency on a project that has less than significant emissions and for which there is no public concern. Instead, staff would only require an indemnification agreement.

| California Environmental Quality Act Determination | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less Than Significant* | Significant* | ||||

| District Discretion | District Is Lead* | District Is Responsible* | District Is Lead* | District Is Responsible* | |

| Public Concern† | Indemnification agreement and letter of credit required | Indemnification agreement and letter of credit required | Indemnification agreement and letter of credit required | Indemnification agreement and letter of credit required | |

| No Public Concern† | Indemnification agreement required | Nothing required | Indemnification agreement and letter of credit required | Indemnification agreement required | |

Source: San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District (district).

* Under regulations adopted to implement the California Environmental Quality Act, a proposed project can be considered “significant” or “less than significant” based on the amount of air pollution generated by the project. The statute also identifies public agencies involved in the approval of the project as either lead agency or responsible agency, where the lead agency has primary reviewing responsibility.

† At the district’s discretion, it considers certain projects to be of public concern and thus more likely to generate litigation. Although the list of projects that are of public concern changes, in recent years the district has considered projects such as dairy operations, oil and gas refineries, and winery fermentation tanks to be projects of public concern.

Despite having a published policy and an internal methodology, the district does not always follow either the policy or the methodology when obtaining indemnification agreements and letters of credit from permit applicants. We reviewed 19 projects for which, based on the district’s policy and methodology, the district should have required indemnification agreements and letters of credit. For seven of the 19 projects, the district did not require indemnification agreements and letters of credit consistent with its policy or internal methodology. In three of these seven instances, the district was the lead agency, and, under the district’s policy, it should have required indemnification agreements and letters of credit. When we asked why the district did not require these documents, a deputy air pollution control officer stated that the district has never required indemnification agreements for all projects for which the district is the lead agency because it wants to avoid placing an unnecessary burden on permit applicants. For example, because the district could be the lead agency for a project that involves little risk of litigation, such as a change in equipment that actually reduces harmful emissions, it might be reasonable for the district to use its discretion.

For the remaining four projects, the district was a responsible agency, and the projects were for facilities or operations that the district deemed to be of public concern. According to a deputy air pollution control officer, the district can require indemnification agreements and letters of credit for potentially controversial projects, but it makes that risk management decision on a case by case basis, taking into account several factors. For two of these projects, the district documented its reasons for not requiring the indemnification agreements and letters of credit, providing reasonable justifications that the project risks did not appear to merit them. The district did not document its rationale for not requiring indemnification agreements and letters of credit from the other two projects, both dairies, but it indicated to us that it did not require indemnification for one because the project did not involve an increase in emissions. For the other project, the district thought it had a valid letter of credit from another project by the permit applicant and thus did not need additional security. However, as we discuss later, we found that this letter of credit had expired.

As a result of its contradictory guidance and practices, the district did not always treat applicants with similar projects consistently. For example, for two projects involving wineries, the district, as the lead agency for both projects, should have required an indemnification agreement and a letter of credit under its published policy. However, it required these documents for one project but not the other. The district’s director of permit services stated that the district did not ask for an indemnification agreement and a letter of credit from one of the applicants because the project would not result in an increase in emissions. The director of permit services acknowledged that the district did not follow its policy in this instance and stated that the district needs to revise its policy.

We also identified two projects involving the dairy industry, an industry that the district identified in its internal procedure memo as one of public concern and thus requiring indemnification agreements and letters of credit. The dairy projects both involved reducing or redistributing the herds, meaning the projects would not increase either dairy’s emissions. Under district rules, a permitted polluter must obtain a new permit if there is a substantial change in projected emissions, even if the emissions will decrease. However, for these two similar projects, the district required an indemnification agreement and a letter of credit for one and not the other. When we brought this inconsistency to the district’s attention, the director of permit services told us that, unless directed by district counsel, the district does not require indemnification agreements for projects with no increase in emissions.

According to a district deputy director, the district does not always require indemnification agreements because it does not want to be overly burdensome. Although the district’s position may be reasonable, as a project that reduces emissions is unlikely to result in litigation, it does not explain why the district has a practice that differs from its written policy and methodology or why similar projects are treated differently. Additionally, the district did not document the reasons for its decisions in five of the seven instances when it did not follow its published policy or internal methodology, thus decreasing the transparency of its actions. Although the district may feel it necessary to use discretion in its decisions, without documentation to support its reasons for deviating from its policy and methodology, the district cannot demonstrate transparency and that it treats similar projects fairly. After we discussed these concerns with the district, it published a revised policy in March 2016. The revised policy no longer requires the district to obtain an indemnification agreement or letter of credit. Instead, the policy provides discretion by specifying that each decision is based on a case by case analysis of certain factors, such as potential litigation risk and potential for significant impacts, among others. The policy also requires the district to document its reasoning for whether to require an indemnification agreement or letter of credit.

Further, the district’s indemnification agreements that we reviewed differed from its published policy in place during our review. Although the district’s policy states that the a permit applicant will bear the burden of liability for potential litigation and the expense of such litigation, the district’s indemnification agreement only requires a permit applicant to pay the litigant’s attorney’s fees and court costs, and it does not require the applicant to pay the district’s costs to defend itself. When we asked the district why its policy and indemnification agreement are not consistent, the district’s counsel stated that the policy and indemnification agreement should be read together. However, the published policy, which is available to the public, may lead the public to believe that the district’s indemnification agreement requires certain permit applicants to cover the district’s entire legal costs and that such situations would leave the district with no responsibility for legal expenses related to approving CEQA projects.

We also noted lapses in the district’s document retention and in its maintenance of indemnification agreements and letters of credit that could put the district at risk in the event of litigation. During our audit, the district had difficulty compiling a complete list of all the indemnification agreements and letters of credit it required for the past 5 years. The list initially compiled by the district was missing information for 24 of the 72 projects listed. The district later provided an updated version. However, we noted that one of the 19 projects we reviewed should have been on the updated list because it had a letter of credit but was not. Without a complete and accurate list, the district cannot ensure that it has the level of protection it sought when it required indemnification agreements and letters of credit. In another case, the district’s list indicated that the district had asked for a letter of credit when it had not. We also found a letter of credit that expired before the date set forth in the indemnification agreement, yet the district did not request a renewal or document its reasoning for not requiring a renewal, leaving the district without the financial security it intended. The district may have had difficulty in providing a complete and accurate list because a staff person in its legal department maintained the signed documents, while another staff person from its permitting department maintained the initial communication with the applicant, thus complicating the district’s ability to identify which projects required these agreements and also to locate such documents. When we brought these concerns with documentation and file maintenance to the district’s attention, the director of permit services acknowledged that a central location to maintain all of these records might provide for better access when questions arise about the agreements. The district has since changed its practices, and its permitting department now maintains all records.

When the district does require letters of credit, there is a cost to the permit applicant. To determine the extent of the cost of securing letters of credit by the permit applicants, we contacted nine applicants from our selected test items for which the district required letters of credit. The district requires only 10 letters of credit on average each year. We found that the costs for the letters of credit for the five applicants who spoke to us and provided supporting documentation ranged from $625 to about $1,400 per year. To provide context, the costs of the associated permits for which the letters of credit were required ranged from $1,900 to $15,000 and averaged $8,400. According to information we obtained from our selection of applicants, the permit applicants paid the costs to their banks, and these costs varied based on the applicants’ credit. A bank may charge a large business with better credit less than it would charge a business with poorer credit.

Recommendations

To ensure consistency among its published policy, internal methodology, and indemnification agreements so that permit applicants are aware of the district’s requirements and are treated equally, by July 2016 the district should update its internal methodology and indemnification agreements to contain equivalent information that reflect its revised published policy.

To make certain that it can demonstrate consistency and transparency in its decision making process when it determines which permit applicants it requires to provide additional financial security, the district—after it updates its guidance documents—should follow its revised published policy and updated internal methodology for requiring indemnification agreements and letters of credit.

To ensure that the district is adequately protected from the costs of litigation, it should develop a protocol to maintain all required legal documents accurately and to make sure that those documents remain in effect. By July 2016, the district should adopt such a protocol for management of its centralized system for requesting, tracking, storing, and following up on indemnification agreements and letters of credit.

We conducted this audit under the authority vested in the California State Auditor by section 8543 et seq. of the California Government Code and according to generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives specified in the Scope and Methodology section of the report. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Respectfully submitted,

ELAINE M. HOWLE, CPA

State Auditor

Date: April 5, 2016

Staff:

Tammy Lozano, CPA, CGFM, Audit Principal

Nathan Briley, J.D., MPP

Kelly Reed, MSCJ

Karen Wells

Legal Counsel:

Richard B. Weisberg, Sr. Staff Counsel

For questions regarding the contents of this report, please contact Margarita Fernández, Chief of Public Affairs, at 916.445.0255.