Introduction

Background

The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) is responsible for constructing, improving, and maintaining California’s highway system (state highway system). The state highway system is composed of more than 50,000 lane miles, more than 13,100 bridges, and an estimated 205,000 drainage culverts.1 It includes interstate highways, U. S. highways, and state highways. These highways are also referred to as routes. For example, the state highway system includes State Highway 50, which runs from Sacramento to the Nevada state line, and Interstate 5, which runs north and south through California. The state highway system does not include county highways and local roads.

Our review focused on the maintenance program, which Caltrans’ division of maintenance (maintenance division) administers. Unlike the SHOPP, which handles more significant and costly rehabilitation projects, the maintenance program focuses on preventative work and corrects small problems before they worsen and require more costly repairs. State law defines maintenance as the preservation and upkeep of roadway structures in the safe and usable condition to which they have been improved or constructed. The maintenance program includes pavement, bridges, roadside and drainage, traffic guidance, and electrical maintenance. Maintenance also includes the special or emergency maintenance or repair necessitated by accidents, weather conditions, slides, settlements, or other unusual or unexpected damage of a roadway, structure, or facility. Maintenance does not include construction of new assets or rehabilitation or reconstruction of roadways. However, according to Caltrans, adequate maintenance can significantly reduce future SHOPP costs for roadway rehabilitation.

Examples of Field Maintenance Activities

- Sealing cracks and patching potholes on pavement

- Clearing vegetation and drainage

- Picking up litter and debris

- Removing graffiti

- Maintaining and painting bridges

- Replacing highway lighting and traffic signals

- Preserving roadway striping, signs, and guardrails

- Removing snow, patrolling for storms, controlling floods and slides

Source: California Department of Transportation's Maintenance Manual, volume II.

The maintenance program consists of two types of maintenance work: highway maintenance and field maintenance. Highway maintenance includes more significant work to repair pavement, bridges, and drainage culverts, among other things. For example, highway maintenance work includes different types of surface treatments to extend the service life of a segment of pavement. These treatments keep the roadway safe and in usable condition, but they do not include structural capacity improvement or reconstruction. Caltrans generally hires contractors to perform this work.

Field maintenance, on the other hand, is generally performed by maintenance division staff and includes activities such as repairing minor pavement damage, clearing vegetation, picking up litter, removing graffiti, and other activities as listed in the text box. Districts generally identify field maintenance work in two ways: maintenance personnel travel all highways to observe conditions and identify maintenance needs, or the public submits service requests notifying the maintenance division of needed maintenance.

Funding for the Maintenance Program

In the state budget each year, the Legislature appropriates funding for Caltrans’ programs, including the maintenance program. California’s budget process generally uses incremental budgeting, which employs a department’s current level of funding as a base amount. State law requires Caltrans to prepare a five‑year maintenance plan (maintenance plan), which it must update every two years, as the basis for its budget request. The plan addresses the maintenance needs of the state highway system but includes only maintenance activities that could result in increased SHOPP costs if not performed. The maintenance plan attempts to balance resources between SHOPP and maintenance activities to achieve identified milestones and goals at the lowest possible long‑term cost. State law also requires Caltrans to develop a budget model to achieve this balance of resources.2 Additionally, if the maintenance plan recommends increases in maintenance spending, the maintenance plan is supposed to identify projected future SHOPP costs that would be avoided by implementing that increased maintenance spending.

As Table 1 shows, the maintenance program received approximately $1.4 to $1.5 billion in funding in each fiscal year from 2010–11 through 2014–15. This amount represented approximately 14 percent of Caltrans’ total annual funding in fiscal year 2014–15. The maintenance program receives nearly all of its funding from the state highway account, the fund in which the State accumulates most of the revenues from gasoline taxes. Other funding sources for the maintenance program include federal funds that the maintenance division uses for pavement projects and bridge inspections, which make up approximately 8 percent of its total funding, and reimbursements for work that the maintenance program performs for local agencies.3

| Fiscal Years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010–11 | 2011–12 | 2012–13 | 2013–14* | 2014–15* | |

| State Highway Account | |||||

| Appropriation | $1,259 | $1,406 | $1,321 | $1,366 | $1,413 |

| Expenditures | 1,259 | 1,395 | 1,311 | 1,327 | 988 |

| Unspent | 0 | 11 | 10 | 39 | 425 |

| Federal Trust Fund | |||||

| Appropriation | 103 | 105 | 117 | 118 | 119 |

| Expenditures | 92 | 102 | 111 | 97 | 23 |

| Unspent | 11 | 3 | 6 | 21 | 96 |

| Total appropriations | $1,362 | $1,511 | $1,438 | $1,484 | $1,532 |

| Total expenditures | 1,351 | 1,497 | 1,422 | 1,424 | 1,011 |

| Total unspent | $11 | $14 | $16 | $60 | 521 |

| Percentage of appropriations expended | 99% | 99% | 99% | 96% | 66% |

Sources: State Controller’s Appropriation Control Ledger and Budgetary/Legal Reporting System for fiscal years 2010–11 through 2014–15.

* The California Department of Transportation still has additional fiscal years to spend against its appropriations for fiscal years 2013–14 and 2014–15.

Caltrans has one year to spend or commit all or part of an appropriation for future expenditures and then two additional years to pay off such expenditures from its appropriation of funds. After this three‑year period, any unspent funds revert to the originating fund for future reappropriation. The maintenance division spent most of its maintenance program funding that was appropriated in fiscal years 2010–11 through 2012–13, but it still has time to spend amounts appropriated in the most recent two fiscal years. We noted that approximately $144 million appropriated in the two years before our audit period had reverted to the state highway account during our audit period. The reverted funds generally resulted from the effects of the economic downturn: cost‑savings the maintenance division achieved on projects as prices decreased, an influx of funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (recovery act), and funds it did not spend when it complied with the governor’s 2009 executive order to halt purchases of new vehicles.

In each of the first three fiscal years of our audit period (2010–11 through 2012–13), the maintenance division spent 99 percent of its total appropriation. During the last five fiscal years, the maintenance division has spent about one‑fourth of its appropriations on contracts, primarily for highway maintenance.

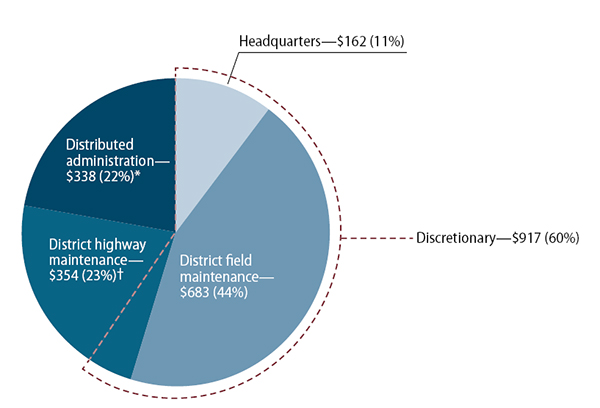

The maintenance division has discretion in distributing the major part of its maintenance program appropriation. Figure 1 shows how headquarters allocated the roughly $1.5 billion the maintenance program received in fiscal year 2014–15. Included in the total is an appropriation of approximately $338 million for distributed administration and equipment programs (administration program).4 The Budget Act of 2014 specified amounts that must be spent for certain highway maintenance program items, including major highway maintenance pavement contracts and storm water discharge: $231.7 million and $50.6 million, respectively. The remaining $917 million is discretionary. From these discretionary funds, the maintenance division allocated an additional $72 million for highway maintenance and $682.7 million for field maintenance to Caltrans’ 12 districts, and $161.9 million for headquarters in fiscal year 2014–15.

The $161.9 million the maintenance division allocated was for overhead and other costs to the following four headquarters divisions: maintenance, engineering services, procurement and contracts (specifically, warehouse), and audits and investigations. The allocation was primarily for employee costs, external and interdepartmental contracts, and other general expenses. Specifically, in fiscal year 2014–15, the maintenance division retained $128.4 million and allocated $17.5 million to the division of engineering services, $15.6 million to the warehouse, and $317,000 to audits and investigations. In fiscal years 2010–11 through 2014–15, the allocation for these other headquarters’ functions ranged between 14 and 20 percent of program funding, excluding distributed administration program costs.

Figure 1

California Department of Transportation Maintenance Program Funding Allocation for Fiscal Year 2014–15 (in Millions)

Source: California Department of Transportation’s financial system.

* Administration program costs are the indirect costs of a program, typically a share of the costs of the administrative units serving the entire department (for example, legal, personnel, and accounting). Distributed administration costs represent the distribution of the indirect costs to the various program activities of the department.

† Highway maintenance includes $231.7 million for major maintenance pavement contracts and $50.6 million for storm water discharge, appropriated separately in the Budget Act of 2014.

Caltrans received $2.5 billion in federal funds in 2009 through the recovery act, including $56.2 million that the California Department of Finance approved for the maintenance program. According to reports from the California Division of the Federal Highway Administration as of September 30, 2015—the last day recovery act funds were available—Caltrans has spent 99.7 percent of recovery act funds, including the funds approved for the maintenance program. Caltrans asserted that the unspent $7.9 million represented savings from projects for other programs that were completed under budget.

Examples of the Maintenance Division’s Offices at Headquarters

- Pavement Management and Performance

- Structure (bridge) Maintenance and Investigations

- Roadway Maintenance

- Maintenance Equipment and Training

- Budgets and Planning

- Maintenance Management Systems and Studies

- Administration Management

- Emergency Management

Source: California Department of Transportation headquarters division of maintenance organization chart.

The Maintenance Program’s Organizational Structure

The maintenance division has staff at Caltrans’ headquarters located in Sacramento and at Caltrans’ 12 districts. The districts and their counties are shown in Figure 2. The maintenance division is divided into several offices at headquarters, including those shown in the text box. Headquarters is responsible for establishing policies, providing technical assistance to the districts, and reviewing districts’ compliance with standards and policies. At headquarters, the chief of the maintenance division (division chief) has overall responsibility for the statewide maintenance program. The division chief is responsible for establishing goals, developing justification for and documenting resource needs, and determining resource allocations among the districts.

Figure 2

California Department of Transportation Districts

Source: California Department of Transportation.

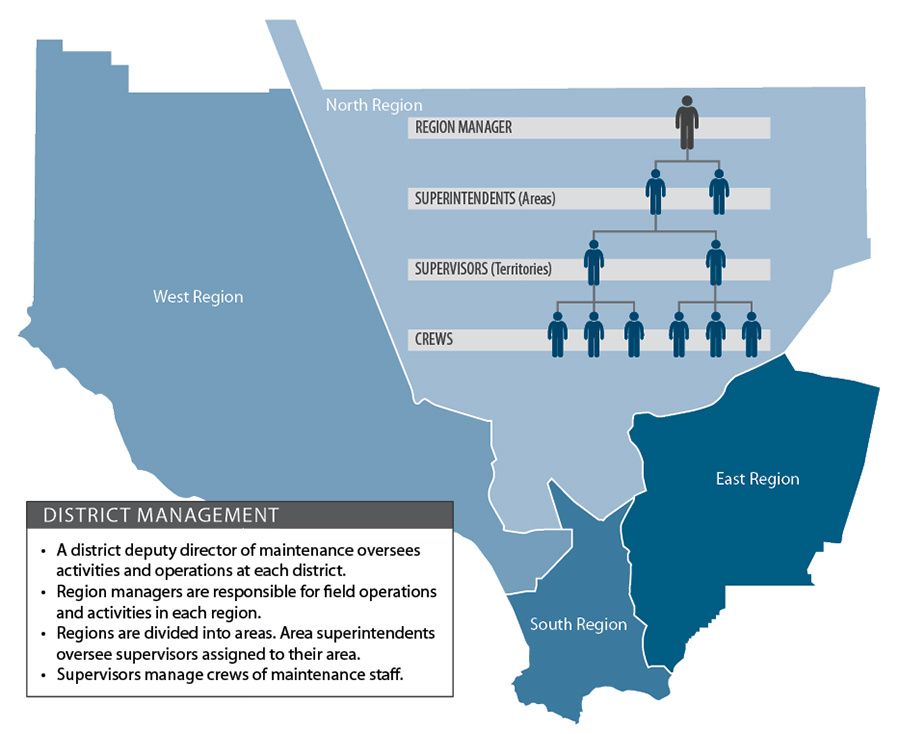

The maintenance division structures its management according to geographic areas within each of Caltrans’ 12 districts. Specifically, a deputy district director of maintenance (district maintenance deputy) directs maintenance efforts at each of the 12 districts. District maintenance deputies oversee district activities and communications, engineering, and region manager operations; they are also responsible for allocating resources within their respective districts, updating district plans to achieve expected goals, and reviewing and approving region work plans. Each district is divided into regions, and region managers are responsible for field operations and activities within each region. Regions are further divided into areas. Area superintendents are responsible for activities within their assigned areas, and they oversee the supervisors of maintenance staff crews. Each supervisor is also responsible for specific segments of the state highway system and specific field maintenance activities within a superintendent’s area, such as landscaping. Figure 3 illustrates the management structure using district 7 (Los Angeles) as an example.

Figure 3

California Department of Transportation Districts

Source: California Department of Transportation’s maintenance manual and district 7 (Los Angeles) maintenance region boundary map.

The maintenance division has provided a manual of guidance and a computer system to help its staff manage maintenance work. The maintenance manual presents general practices and procedures intended to provide for a uniform approach to maintaining the state highway system. The maintenance division’s maintenance staff use its integrated maintenance management computer system (maintenance management system) to plan, perform, record, and manage maintenance work. The maintenance management system allows supervisors and managers to inventory assets, track work performed and the associated costs, manage materials and equipment, and provide decision‑making tools to managers and supervisors. For example, a maintenance supervisor must fill out a work order in the maintenance management system for field maintenance work. The work order records the expenditures of labor, production units, vehicles, and materials, and the location where the crew performed the work.

System for Evaluating Maintenance Performance

The maintenance division has a program for evaluating the maintenance level of service or performance that helps determine how well it maintains the state highway system under the maintenance program. The maintenance division annually conducts maintenance performance evaluations (service evaluations) for several categories of maintenance activities, representing a snapshot of the roadway conditions. These evaluations are separate from the general reviews maintenance personnel perform to identify needed maintenance work mentioned previously. Some examples of the categories are shown in Table 2. The maintenance division calculates maintenance performance scores (service scores) for these categories. However, the maintenance division has set service score goals only for picking up litter and debris, maintaining lane striping, and repairing guardrails. According to the maintenance performance reports, these goals apply only to the state overall, not to the individual districts.

Level of Service Rating System for Litter

Pass (100): no deficiency

Need 1 (50): one small area

Need 2 (0): more than one area

Source: California Department of Transportation's Fiscal Year 2014–15 Maintenance Level of Service Statewide Report Executive Summary.

To perform the service evaluations, the maintenance division divides the state highway system into one‑mile segments. It annually conducts service evaluations on a random sample of 20 percent of the one‑mile segments within each district. Evaluators visually observe highway attributes to determine whether conditions are deficient and to determine the overall needs of each segment. Specifically, evaluators inspect a one‑mile segment using a rating system such as the one shown in the text box and provide a score for that segment. Evaluators total and average the points for all the evaluated segments to calculate that district’s service score. Low service scores indicate that the district has a high maintenance need. The maintenance division then averages all of the districts’ service scores to calculate an overall statewide score for each category, with the exception of storm water. Rather than using the established service score goals to measure district performance, the maintenance division has established spending goals for five maintenance activities, shown in Table 2 , that it requires each district to meet. We discuss the maintenance division’s approaches for evaluating maintenance performance further in the Audit Results.

| Service Score Category | Service Score is Calculated | Service Score Goal Has Been Set | Spending Goal Has Been Set |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible Travelway | |||

| Cracks | Yes | No |

Yes |

| Potholes | Yes | No |

No |

| Paved shoulders | Yes | No |

No |

| Rigid Travelway | |||

| Joint separation | Yes | No |

No |

| Slab failure | Yes | No |

No |

| Ramps | Yes | No |

Yes |

| Drainage | |||

| Surface drains | Yes | No |

No |

| Ditches | Yes | No |

No |

| Slopes | Yes | No |

No |

| Roadside | |||

| Vegetation | Yes | No |

No |

| Fences | Yes | No |

No |

| Litter and debris | Yes | Yes |

Yes |

| Graffiti | Yes | No |

No |

| Traffic Guidance | |||

| Lane striping | Yes | Yes |

Yes |

| Raised markers | Yes | No |

No |

| Signs | Yes | No |

No |

| Guardrails | Yes | Yes |

Yes* |

| Landscaping | |||

| Weed control | Yes | No |

No |

| Mulch | Yes | No |

No |

| Irrigation system | Yes | No |

No |

| Storm Water | |||

| Storm water | NA | NA |

Yes |

Sources: California Department of Transportation’s (Caltrans) Fiscal Year 2014–15 Maintenance Level of Service Statewide Report Executive Summary and maintenance division expenditures dashboards.

NA: While the maintenance division has set a spending goal for storm water, storm water represents funding Caltrans receives that is not for any particular maintenance activity so the maintenance division does not calculate a service score or set a service score goal for storm water.

* Caltrans set a spending goal for safety barriers, which include guardrails.

Scope and Methodology

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee (audit committee) directed the California State Auditor to review the methods Caltrans used to make spending decisions related to the maintenance program. Table 3 lists the objectives that the audit committee approved and methods we used to address those objectives.

| Audit Objective | Method | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Review and evaluate the laws, rules, and regulations significant to the audit objectives. | Reviewed relevant laws, rules, regulations, and other background materials related to the maintenance program. |

| 2. | Identify the actual, estimated, and proposed statewide expenditures for the program. Additionally, identify any trends in expenditures and reasons for the trends. |

For our audit period of July 1, 2010, through June 30, 2015, we did the following:

|

| 3. | Identify the sources of funding for the program and assess the method used by the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) to determine the total amount of funding allocated to the statewide program each year. Additionally, determine whether Caltrans has taken advantage of all opportunities to maximize funding for the program and whether any additional sources of funding exist. |

|

| 4. | Review and assess Caltrans’ method of allocating program funding throughout the State and determine whether the distribution of funding is fair and reasonable. |

|

| 5. | To the extent possible, identify the current socioeconomic demographics of each district receiving funding. Additionally, determine the amounts received by those districts in each of the years reviewed. |

|

| For three districts, including District 7 (Los Angeles and Ventura counties), perform the following to determine whether program funding is used in an effective and timely manner: | Selected two additional districts—district 4 (Oakland) and district 6 (Fresno)—based on geographic location, traffic volumes, population, socioeconomic demographics, and maintenance performance levels. | |

| a. Evaluate the methodology used to estimate and propose maintenance expenditures pertaining to the district. | Confirmed with district deputy directors of maintenance at the three selected districts that they do not estimate and propose district maintenance expenditures. Rather, the maintenance division at headquarters determines the districts’ allocations. | |

| b. Review and assess the method used to identify and prioritize maintenance projects. |

|

|

| c. Determine the extent to which the program is properly managed and meeting its goals and objectives. |

|

|

| d. For a selection of maintenance projects, determine whether the costs of the projects are reasonable, the completion is timely, and the reasons for any backlogs that exist. |

|

|

| e. For a selection of program expenditures, determine whether they were reasonable and allowable. |

|

|

| f. Determine the extent to which the district hires, monitors, and evaluates contractors. |

|

|

| g. Identify total available and filled positions, employees, and vacancies in the program and the impact vacancies have on the program. |

|

|

| 7. | Determine if Caltrans is on track to spend the remaining American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (recovery act) funding before it reverts to the federal government and the extent to which these funds can and are being used for the program. |

|

| 8. | Review and assess any other issues that are significant to the audit. | Reviewed projects included in the 2000 through 2012 State Highway Operation and Protection Program (SHOPP) plans to determine whether projects had been performed on highways with low and high spending for field maintenance in the districts we reviewed. |

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of the Joint Legislative Audit Committee’s audit request 2015‑120 and information and documentation identified in the table column titled Method.

Assessment of Data Reliability

In performing this audit, we obtained electronic data files extracted from the information systems listed in Table 4. The U.S. Government Accountability Office, whose standards we are statutorily required to follow, requires us to assess the sufficiency and appropriateness of the computer‑processed information that we use to support our findings, conclusions, and recommendations. Table 4 describes the analyses we conducted using the data from these information systems, our methods for testing them, and the results of our assessments. Although these determinations may affect the precision of the numbers we present, there is sufficient evidence in total to support our audit findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

| Information System | Purpose | Method and Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) Integrated Maintenance Management System (IMMS) Maintenance work data from |

|

|

Not sufficiently reliable for these audit purposes. Although this determination may affect the precision of the numbers we present, there is sufficient evidence in total to support our audit findings, conclusions, and recommendations. |

Position Tracking Automated System (PTAS) Position data from July 1, 2011, through June 30, 2015 |

|

|

|

Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI) Arc Map system Postmile latitude and longitude coordinates as of September 22, 2015 |

To identify the latitude and longitude coordinates for postmile points on California state highways. |

|

|

Maintenance Service Request System Maintenance service requests submitted from July 1, 2010, through |

To determine the status of maintenance service requests submitted through Caltrans’ online system for Caltrans districts 4, 6, and 7. |

|

Not sufficiently reliable for these audit purposes. Although this determination may affect the precision of the numbers we present, there is sufficient evidence in total to support our audit findings, conclusions, and recommendations. |

| A Caltrans‑generated data file containing climate and traffic volume data for state highways as of 2010. |

To determine the climate and traffic zones of the state highway system in Caltrans districts 4, 6, and 7. |

|

|

Consultants to Government and Industry Advantage system (Advantage) Financial data from July 1, 2010, through June 30, 2015 |

To make a selection of highway maintenance program expenditures, bridge projects, and pavement projects in Caltrans districts 4, 6, and 7. |

|

Complete for these audit purposes. |

| Advantage |

|

|

Not sufficiently reliable for these audit purposes. Although this determination may affect the precision of the numbers we present, there is sufficient evidence in total to support our audit findings, conclusions, and recommendations. |

U.S. Census Bureau, 2013 American Community Survey Five‑Year Estimates Socioeconomic information related to median income and race/ethnicity by census tract |

To determine the median income and race/ethnicity that composes the majority of each census tract in Caltrans districts 4, 6, and 7. |

We did not assess the reliability of these data because, according to standards of the U.S. Government Accountability Office, it is not necessary to conduct procedures to verify information that is used for widely accepted purposes and is obtained from sources generally recognized as appropriate, such as the U.S. Census. |

Undetermined reliability for this audit purpose. |

State Controller’s Office Appropriation Control Ledger |

To determine the maintenance division’s expenditures for each fiscal year from July 2010 through June 2015. |

We assessed the reliability of these expenditure records by reviewing testing of the appropriation control ledger system’s major control features performed as part of the State’s financial and federal compliance audits. |

Sufficiently reliable for the purposes of presenting data on expenditures. |

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of various documents, interviews, data obtained from Caltrans, and data from State Controller’s Office Appropriation Control Ledger.

Footnotes

1 A lane mile is a unit of measure for pavement measuring one mile long and one lane wide. A mile stretch of a two‑lane road equals two lane miles, and a segment of road one mile long and four lanes wide is four lane miles. Go back to text

2 Caltrans includes the statutorily required budget model in its maintenance plan in the section titled “Analysis of Alternative Levels of Maintenance Investment,” not to be confused with the section of the maintenance plan titled “Maintenance Program Budget Model,” which is discussed in more detail in the Audit Results. Go back to text

3 For example, Caltrans personnel may perform routine maintenance of traffic control systems or facilities on county‑owned roads or city‑owned streets through cooperative agreements. Go back to text

4 Administration program costs are the indirect costs of a program, typically a share of the costs of the administrative units serving the entire department (for example, legal, personnel, and accounting). Distributed administration costs represent the distribution of the indirect costs to the program activities of a department. Go back to text