Audit Results

The City of Irvine Did Not Ensure That the Orange County Great Park Review Used Appropriate Industry Standards, and It Conducted a Flawed Selection Process of Firms to Perform the Review

The city of Irvine did not ensure that consultants conducting the performance review of Orange County Great Park contracts (park review) applied the most appropriate audit standards for the goals of the review, and Irvine did not follow its established processes for awarding a key contract related to the park review. City council members stated that they wanted an independent audit; however, in developing its request for proposal (RFP) in 2013, Irvine determined that the park review would be conducted in accordance with Statements on Standards for Consulting Services (consulting standards) established by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) even though these standards do not require the reviewer’s independence and are less rigorous than other applicable AICPA and industry standards.1 In our judgment, the use of less rigorous standards when members of the city council expressed a desire for an independent audit reduced the value of the park review to the city council and eroded confidence in the reviewer’s work.

Further, in June 2013, Irvine completed a competitive process to select the firm—Hagan, Streiff, Newton & Oshiro, Accountants, PC (HSNO)—that would conduct the park review. In selecting this firm, Irvine increased its original scores for HSNO near the completion of the process, and they based a substantial portion of their evaluation on the bidders’ interview performance, even though the RFP did not list interview performance as an evaluation criterion. Irvine also did not inform bidders that it would be considering interview performance or would be weighting it as heavily as it did in making its decision. Changing the selection criteria used to evaluate potential consultants without adequately informing bidders or the public about these changes unnecessarily cast doubt on the impartiality of the selection process and increased the risk that the city did not select the most appropriate vendor to meet its needs. Finally, Irvine’s RFP anticipated the possibility of additional work. This all but guaranteed that the firm it selected for the park review would also receive a second, no‑bid contract instead of Irvine conducting another competitive process to ensure that it obtained the best value for its contract.

Irvine’s Request for Proposal Did Not Ask Consultants to Use Audit Standards Appropriate for Achieving the City’s Goals for the Park Review

In seeking consultants to conduct the park review, Irvine did not specify in its RFP that these firms needed to follow standards and procedures that would result in the thorough, independent evaluation of Great Park contracts that the city council members had described to the public. In January 2013, the city council unanimously approved the development of an RFP for a comprehensive contract compliance and forensic audit; however, the RFP it approved in March 2013 called for a performance review of certain contracts associated with the development of Great Park. In that city council meeting, as well as in subsequent meetings and in the media, council members referred to the review using various terms, including performance audit, contract compliance review, forensic audit, and audit. The term audit appears frequently in meeting minutes and in media references to the park review even though the RFP did not ask for an audit. Indeed, the word audit appears only in the section of the RFP requesting information on bidding firms’ experience and qualifications and not in the title or scope of services. The type of engagement—consulting services—for which Irvine ultimately contracted was not nearly as rigorous an assignment as the descriptions of the park review members of the city council conveyed publicly.

The auditing industry has professional standards that outline practices designed to ensure that auditors perform their work to a certain level of independence and quality. For example, according to government auditing standards issued by the Comptroller General of the United States and published by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, government auditing is essential to providing accountability to legislators, oversight bodies, others charged with governance, and the public. These professional standards—commonly referred to as generally accepted government auditing standards (GAGAS)—state that audits provide an independent, objective, nonpartisan assessment of the stewardship, performance, or cost of government policies, programs, or operations, according to the type and scope of the audit. Further, the AICPA promotes and maintains various professional standards for its members, depending on the type of engagement. State law also requires local government auditors to use either GAGAS or standards promulgated by the Institute of Internal Auditors, an industry member association, when conducting audit work. The California State Auditor’s Office performs its work in accordance with GAGAS. Table 3 outlines levels of professional standards related to auditing and auditors and key requirements included in those standards. As the table shows, the standards Irvine required HSNO to follow in the park review are not nearly as robust as others, such as GAGAS.

When we inquired of the subcommittee members about the decision to have the park review conducted in accordance with AICPA consulting standards, one member stated that the subcommittee did not discuss the audit industry standards, and the other explained that she was not familiar with audit standards. Further, current city staff could not explain why Irvine chose to have the park review conducted under consulting standards. We find it puzzling that Irvine decided to use these standards given that the city had contracted for a review of Great Park, published in 2012, in which the firm used AICPA standards called agreed‑upon procedures and given that the city’s financial auditors reported that they conduct their annual audit according to GAGAS. A former city employee who worked with the subcommittee member who proposed the park review stated that he recommended the park review be done according to agreed‑upon procedures, which, as Table 3 notes, is a higher standard.

Based on statements in city council meetings and the original council action requesting an audit, Irvine would have been better served had it directed consultants to conduct the park review using standards that require independence. During the January 2013 meeting in which the city council considered the request to approve the park review, four of the five council members explicitly stressed the importance of an independent audit. However, as Table 3 indicates, consulting standards do not require independence. According to the AICPA, independence means the absence of relationships that may appear to impair an auditor’s obligation to be impartial, intellectually honest, and free of conflicts of interest. In fact, one firm that had worked with Irvine in the past sent a letter to city staff stating that it declined to bid on the park review because it believed that consulting standards would reduce its ability to operate as a neutral, independent analyst. That firm stated it would find it difficult, if not impossible, to render an objective opinion that would not favor certain stakeholders, leaving the resulting report subject to criticism. By selecting consulting standards rather than more rigorous standards, Irvine increased the risk that the park review would lack an appearance of independence.

Selected Standards |

|

|

|

Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards (GAGAS)* |

International standards for the Professional Practice of internal auditing—Assurance service† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) standards for consulting services |

AICPA standards for Attestation–Agreed‑Upon Procedures engagements |

||||

Irvine required Hagan, Streiff, Newton & Oshiro, Accountants, PC (HSNO) to use these standards for the orange county Great Park contracts review (park review) in 2013 |

The city of irvine (Irvine) contracted in 2011 for a review of certain Great Park contracts using these standards |

State law requires audits conducted by public agency employees—or entities that conduct audit activities of Public agencies—to use either of these standards |

|||

Review requires objectivity, which is the obligation to be impartial, intellectually honest, and free of conflicts of interest |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

Review requires independence, which precludes relationships that may appear to impair objectivity |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

The auditor is to withdraw from the engagement if the auditor encounters limitations on its scope or inquiry |

|

✓ |

✓ (or auditor may report limitations) |

✓ | |

Guidelines exist for communicating and conducting the engagement with the person or group being audited and with management or those charged with governance, or the party that engaged the practitioner |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

Practitioner is required to prepare and maintain audit documentation that supports the report |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

Report must state standards used, including limitations on scope of work, reservations, and report’s intended audience |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

Subject to external assessment or peer review |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

Auditor independently develops the audit procedures |

|

|

✓ | ✓ | |

Practitioner develops the procedures or services performed solely by agreement with client |

‡ |

‡ |

|

|

|

* State law requires the state auditor to conduct its performance audits in accordance with GAGAS.

† The International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing is the standards framework issued by the Institute for Internal Auditors.

‡ Under these standards, the practitioner and the specified parties agree upon the procedures to be performed, and the practitioner does not render an opinion or overall assurance of level of risk but only makes conclusions based on the performance of procedures agreed upon with the client.

In addition, consulting standards do not require that firms receive peer reviews. According to GAGAS, peer reviews allow trained auditors from other audit organizations to examine a firm’s quality control systems, which are designed to ensure high‑quality work and the firm’s compliance with applicable professional standards. Irvine’s RFP asked bidders to submit information related to their most recent peer review. However, three of the five firms bidding on the project, including HSNO, which ultimately won the contract, had not undergone a peer review. According to HSNO’s proposal, because the firm performs strictly forensic audits, it is not subject to peer reviews.2 Having appropriate quality controls in place is critical to ensuring that a firm will produce work that will withstand scrutiny and uphold industry standards.

Furthermore, Irvine’s decision to have the park review conducted using consulting standards also allowed for noncommunication and a lower assurance of accurate conclusions in at least one report. GAGAS requires performance auditors to obtain and report the views of responsible officials of the audited entity concerning the findings, conclusions, and recommendations in the audit report as well as any planned corrective actions. GAGAS also explains that providing a draft report with findings for review and comment by responsible officials helps the auditors develop a final report that is fair, complete, and objective; and it offers the auditors the opportunity to evaluate the comments or to modify the final report as necessary. Irvine staff stated that HSNO did not communicate any findings or recommendations to them before it delivered its first report to the city in January 2014. Further, we noted that HSNO was the only firm that did not explain in its proposal for the park review project how or whether it would communicate its findings and conclusions with Irvine’s staff during the audit.

Operating under standards requiring this type of communication with city staff or the city council would have helped identify a faulty conclusion that caused a great deal of unnecessary publicity. In its January 2014 report, HSNO concluded that the vast majority of tax increment revenue, a key component of the expected Great Park financing, had not been remitted to the Great Park Fund. Specifically, HSNO stated that Great Park had not received $38 million of these funds and that HSNO had attempted to determine how the funds were used, but reported that city staff told the firm that doing so was not within the scope of the park review contract. Nevertheless, HSNO reported on these funds in its January 2014 report. This finding led to numerous unnecessary reports by the media and others regarding concerns about the use of the funds. Subsequently, city staff was able to demonstrate how the city accounted for the funds. Had Irvine required HSNO to follow standards requiring it to communicate its intention to report what it believed to be missing funds as a finding and to obtain feedback from Irvine before HSNO publicly issued its report, staff would have had the opportunity to provide the missing information, thus avoiding both damage to the credibility of the report and unnecessary criticism of Irvine and HSNO.

Finally, Irvine did not ensure that Aleshire & Wynder, LLP (Aleshire)—a law firm Irvine commissioned to assist with the park review—followed any particular standards. In its March 2015 report, HSNO stated that it followed consulting standards of the AICPA; however, Aleshire’s March 2015 report made no such claim. Nevertheless, Aleshire titled its report Great Park Audit, which refers to the review as an audit. Further, Aleshire stated that it and HSNO conducted the park review in accordance with a section of an agreement with the Great Park Design Studio—described in the Introduction—that referred to the city being able to conduct a “performance and financial audit” of that agreement.

Had the park review been conducted according to GAGAS, an audit firm and not a law firm would have remained in the lead role. GAGAS allows auditors to seek the assistance of specialists, such as attorneys, when the need arises. In fact, according to its contract and to statements in its March 2015 report, Aleshire’s role was to provide legal services to facilitate HSNO’s work and to assist HSNO; however, as we discuss later in the report, Aleshire took the lead in the park review.

An internal auditor could have provided critical assistance and guidance during the park review, including guidance related to the use of appropriate audit standards. State law requires cities with aggregate spending of $50 million or more to consider establishing an ongoing audit function, which may be accomplished by establishing an internal auditing office within city government. The Association of Local Government Auditors states that an internal auditor function provides many benefits, including enhancing accountability to taxpayers, building credibility with residents, helping ensure that public funds are spent only in the public interest, and providing an independent and objective perspective so that decisions to spend public funds involve balanced and extensive information. As a knowledgeable resource on audit standards and compliance, an internal auditor could have ensured that Irvine required HSNO to complete the park review using a more robust set of standards than consulting standards. Further, an internal audit function could have conducted the park review itself, or it could have ensured that audits performed by an external auditor had an appropriate scope and that contracts were subject to rigorous monitoring. Such activities could have eliminated the expressed concerns of the city manager and one subcommittee member about the appearance of a conflict of interest that prevented staff from helping to manage the park review and simultaneously functioning as subjects of that same review. When we asked the city manager if Irvine had ever considered implementing an internal audit function, he stated that it had not done so during his more than 10 years as city manager.

Irvine’s Selection Process Had Flaws and Lacked Transparency

By not fully publishing and adhering to selection criteria for bidders of the park review, Irvine did a disservice to bidders, and in our judgment it compromised the impartiality and transparency of the selection process. Specifically, Irvine modified and finalized its selection and evaluation process after it had accepted and reviewed bidders’ proposals and interviewed selected firms. In doing so, the city revised the scores it initially gave the proposal from one firm—HSNO—and chose to make interview performance a significant deciding factor in selecting the firm for the park review contract. By changing its selection criteria and the weight it gave to them without notifying potential bidders and after it had completed its evaluation of bidders, we believe Irvine cast significant doubt on the fairness and impartiality of its selection of HSNO as the park review consultant. Based on our analysis of the RFP’s requirements and the city’s selection process, Irvine also increased the risk that the city did not select the most qualified vendor to meet its needs.

For reasons it could not adequately explain, Irvine modified its selection and evaluation process after it had accepted bidders’ proposals and interviewed potential consultants for the park review, and this adjustment strongly favored Irvine’s selecting HSNO as the consultant to conduct the review. According to a city memo, the subcommittee worked with city staff to complete the RFP that the city council approved in March 2013. The process for reviewing bidders’ proposals for the park review consisted of two phases, the second of which was a modification that the RFP did not indicate would be part of the selection criteria. First, city staff reviewed and rated all five bidders’ proposals that the city received in response to the RFP. In the second phase, an interview panel consisting of the two subcommittee members and the then‑director of administrative services, conducted interviews with the top four firms. The city then combined the ratings from the interviews with the scores of the bidders’ proposals and identified HSNO as the highest‑rated firm. In a memorandum requesting approval to award the park review to HSNO, city staff also stated that they reviewed and compared HSNO’s pricing with that of the other bidders and determined it was fair and reasonable. In June 2013, the city ultimately identified HSNO as the highest‑rated firm and initiated a contract with HSNO. The firm would not have secured the highest score, however, if the city had not added the interviews of certain bidders to the selection process—a step in the process that the city’s purchasing agent described as rare. However, she noted that the city has used interviews for projects and services such as city attorney services, a design‑build project, information technology, and other professional services when there was a need to learn more about the bidders’ project approach and to gain clarification related to their written proposals.

Irvine’s Contract Selection Guidelines for Evaluating Proposals Submitted for a Particular Contract

- Compliance with the request for proposal

- References

- Understanding of the project

- Methodology and management approach

- Time allocated to various staff

- Availability of facilities and equipment

- Experience of firm

- Qualifications of project manager

- Proximity of base of operations

- Price

- Criteria specific to the scope of work for a particular project

Source: Irvine’s Service Contracting Guideline Manual.

This addition to the city’s selection process not only allowed the subcommittee members to participate in the selection of a firm for the park review, but it also yielded evaluation measures inconsistent with those listed in the RFP. As the text box shows, Irvine’s Service Contracting Guideline Manual (contracting manual) sets forth criteria by which the city should evaluate firms bidding for requested services. That contracting manual further states that to score firms’ proposals, a selection team should use a standardized rating sheet that corresponds to selection criteria outlined in the relevant RFP. The park review’s RFP stated that Irvine would evaluate the proposals based upon the data presented in response to the RFP and that it would assess proposals based on qualifications, experience, references, methodology, and responsiveness to the RFP. Given these documents, we were surprised to find that the city later decided to base a significant portion of its evaluation of bidders on their performance in the interview, when the interview was not listed in the RFP as something on which bidders would be evaluated.

Although the RFP stated that the city “may” interview the highest‑rated firms, it did not explicitly list interview performance as one of the selection criteria. Although the city is not bound by the State Contracting Manual, the manual’s requirements illustrate best practices in this area. According to the State Contracting Manual, RFPs should contain a description of the factors that agencies will use in proposal evaluation and contractor selection, and the manual specifies that agencies may not change or add to these factors after distributing the RFP without adequate notice to all potential bidders. However, Irvine did not provide such notice when it decided to include interview performance in its selection criteria. As a result, potential bidders—as well as the public—did not receive complete information in terms of the methodology Irvine would use to review bidders’ proposals. Neither city staff nor the subcommittee members who participated in reviewing the RFP, according to documentation we received, could explain why it did not specify interview performance as a selection criterion or why Irvine did not notify potential bidders of the change.

Irvine’s decision to add the bidder’s interview performance—a criterion for which HSNO earned perfect scores from all three members of the interview panel—also caused city staff to modify its evaluation methodology of bidders’ proposals. Irvine’s contracting manual states that the city should determine each criterion and assign it a weight before reviewing bidders’ proposals.3 Although Irvine specified in the park review RFP the selection criteria that it would use to evaluate bidders’ proposals, it did not indicate the weight each criterion would carry in the city’s overall rating of those proposals. Irvine’s purchasing agent, who oversees the contracting of all equipment and services, stated that the city’s standard practice is to include in its RFPs the weights for each selection criterion. In fact, a draft version of the park review RFP included weights for each selection criterion, none of which was an interview. The purchasing agent recalled, however, that she was advised to remove the weights from the park review RFP. Because Irvine omitted the weights that the selection criteria would carry in the city’s evaluation of bidders’ proposals for the RFP, Irvine did not properly inform bidders and the public about the methodology it would use to evaluate the proposals. After it conducted the interviews of the top‑rated firms, Irvine finalized its weighting methodology for the selection criteria, and the interview became the most significant component, representing one‑third of the total evaluation score. The city’s purchasing agent, who was not involved in the selection process, could not explain why interview performance became the most heavily weighted selection criterion. Nonetheless, both subcommittee members indicated that HSNO presented a more comprehensive and experienced ability to complete the park review and the then‑director of administrative services also stated that HSNO made a great presentation. This perspective—coupled with the fact that the city finalized its weighting of the selection criteria after it had conducted its interviews—casts doubt on the impartiality and transparency of the evaluation process.

In addition to the concerns raised about the park review’s selection methodology, the interview process itself raised questions about whether Irvine evaluated bidders according to the needs expressed in the RFP. The RFP’s scope of services stated that after receiving the findings in the consultant’s final report, city staff or the subcommittee could determine whether the consultant needed to perform additional procedures, including those of a more forensic nature. However, in response to questions from potential bidders after the RFP’s distribution, Irvine stated that the park review would not be forensic in nature. Nevertheless, the interview questions included one inquiring whether the bidder planned on using a forensic auditor during the park review and in what capacity. Further, according to our review of the questions the interview panel prepared for each bidder, the panel specifically asked one of the two firms whose proposals the city rated the highest to describe its forensic auditing experience. The interview panel rated this firm’s interview performance notably lower than that of HSNO, a firm that specified in its proposal that it strictly performs forensic audits. Had Irvine chosen to make its desire for a forensic examination clear, firms such as the one questioned about its forensic auditing experience might have structured their proposals differently, and other firms might have chosen to bid on the RFP, potentially resulting in a different firm chosen to conduct the park review.

Irvine rated HSNO higher than other bidders in part because city staff substantially increased the firm’s scores after the interview phase. During the first phase, the initial review of bidders’ proposals, city staff rated HSNO’s proposal as tying for third among the five bidders, with HSNO receiving about 80 percent of the points that the first‑ and second‑place candidates received. However, after the modification adding the second phase interviews, the scores for HSNO’s proposal notably increased—by about 12 percent—whereas the scores for the other proposals remained unchanged. When we asked Irvine’s purchasing agent why the scores for HSNO increased, she recalled that city staff who conducted the review of the proposals initially thought that HSNO’s proposed scope of work did not align with the scope of work specified in the RFP. She stated that after the interview phase, however, the raters probably increased their scores of HSNO’s proposal in certain areas because they had a better understanding of the firm’s proposed work and believed it enhanced the RFP’s scope of work.

Our review further found that HSNO did not provide references that met the standards the city’s RFP required. The RFP stated that proposals must include three references for similar work that the bidder and its proposed team had done within the last three years. However, staff raised concerns that two references that HSNO initially listed in its proposal did not align with the requirements set forth in the RFP. Email correspondence between HSNO and city staff indicated that one of HSNO’s three references related to work completed before the three‑year time frame. This same correspondence further indicated that another of HSNO’s references related to work completed primarily by firm members who would not be working on the park review team. When we asked the purchasing agent about HSNO’s seemingly substandard references, she indicated that city staff accepted different references and that reference checking was performed at the end of the selection process to verify that HSNO provided good services to its clients. However, we question this explanation given that the selection criteria in the RFP stated that references would be one of the criteria upon which proposals would be scored. Further, based on email correspondence, it appears that Irvine only attempted to verify the adequacy of HSNO’s references after it began discussing the nature of the park review with HSNO, which raises additional concerns about the impartiality and transparency of Irvine’s selection of HSNO.

In changing its selection methodology, Irvine made HSNO the top rated‑firm for the park review. By deciding to increase its initial scoring of the firm’s proposal and include interview performance as one‑third of its overall evaluation, Irvine ensured that HSNO received the highest score of all bidders. Had Irvine adhered to its original selection criteria described in the RFP, HSNO would not have been selected as the most qualified firm.

In September 2014, Irvine updated its policies for its proposal review and selection process, and the changes address some of the issues we raised. For example, the new policies require that one or more of the individuals reviewing bids contact references for the highest‑rated firms. Further, the procedures outline how Irvine will use interviews—which remain an optional part of the process—to rate bidders. However, the new procedures for interviews assign a separate score for the interview but do not indicate whether scores from the first part of the process—the proposal document review—may change as a result of the interview. Without this clarification in its policies and without notifying bidders through the published RFP about the complete process the city will use to evaluate bids, Irvine risks using a selection process that is less than fair and impartial.

Irvine’s Contract With HSNO All But Ensured That the Consultant Would Receive a Second, No‑Bid Contract

The RFP that Irvine developed for the park review appeared to encourage bidders to consider the possibility of work beyond the original scope of services. Ultimately this situation contributed to a second contract for HSNO from Irvine for additional work, without HSNO having to compete with other firms for that work. In January 2013, the city council authorized $250,000 for the park review. In March 2013, the city council approved the park review RFP, which led to Irvine’s eventual selection of HSNO to conduct the work. In January 2014, HSNO released a report in which most of the 29 recommendations it made proposed that additional work be performed, such as analyses or review. In a subsequent meeting in January 2014, the city council approved a $400,000 contract for HSNO to address a notable portion of this additional work. The council’s approved motion provided HSNO with a new contract and scope of services without requiring HSNO to bid competitively for this contract. When the contractor is already familiar with the work it will need to accomplish, an agency or government approving a no‑bid contract may be more efficient and cost‑effective than soliciting a competitively bid contract. Nevertheless, in this case, Irvine structured its RFP in a way that encouraged the consultant to suggest the additional work.

Specifically, the RFP contained language suggesting that the possibility for additional work existed. The scope of services stated that the consultant might need to perform procedures of a more forensic nature depending on the findings in the consultant’s final report. Further, the RFP stated that the minimum qualifications that firms had to possess were the capability and resources to perform all services named in the RFP. Those services included prospective forensic services, even though the first addendum to the RFP stated that the park review was not to be forensic in nature. In addition, the RFP’s cost summary required each bidder to provide detailed pricing information—separate from the bidder’s proposed budget for the park review—sufficient to allow flexibility in the event that a more advanced forensic review was required. The first addendum to the RFP reinforced this idea, stating that the council approved $250,000 for the completion of the park review’s scope of services and that bidders should include their rate structures in case the need arose for any additional forensic work. This focus on additional forensic work strongly suggested to potential bidders that Irvine was prepared to appropriate additional funding for more work after completion of the initial scope of work.

Because Irvine’s RFP included language that specified the potential need for forensic capabilities, the requirements in the RFP limited potential bidders and made it more likely that the city would be able to justify a sole‑source contract for additional work from the winning bidder. Irvine’s contracting policies and procedures state that the city may issue a contract without competitive bidding under certain circumstances, including the contractor’s possession of a particularly strong background, history, or experience working on a particular type of project. By structuring the RFP in a way that helped ensure that the winning bidder possessed this strong background and experience, Irvine all but guaranteed that if the city required additional work, it could justify awarding a sole‑source contract to the same firm after that firm completed the initial scope of services.

Although Irvine’s purchasing agent asserted that structuring the RFP in this manner prevented the winning firm from having a distinct advantage in a future competitive bidding process, we disagree. By structuring the RFP to anticipate future work, Irvine encouraged the winning bidder to develop opportunities for such work, thereby giving the winning bidder an advantage in the event of a future competitive process or increasing the likelihood of a sole‑source contract. The purchasing agent also stated it would have been inefficient to stop the review midway through the process to open it up for competitive bidding. However, if the first review was not a forensic review and subsequent work required such ability, it is possible that two separate firms would have provided better services to Irvine, with the first focusing on the contract performance review and the second doing a more in‑depth examination of findings from the first review. By soliciting the procurement in a manner that all but assured a future sole‑source contract for the winning bidder, Irvine missed the opportunity to solicit competitive bids for these services and ensure that the city received the best value for its procurement. Further, Irvine risked the possibility that the winning bidder would structure its work so as to promote the need for additional work through a sole‑source contract.

Although Irvine followed a flawed selection process when it chose HSNO to conduct the park review, we found the city’s processes for selecting the law firms involved in the park review to be reasonable. According to the city manager, Irvine typically does not solicit competitive bids for legal services except when selecting its city attorney. Further, state law relevant to local government procurement does not require competitive bidding for legal services. Finally, state entities that follow the State Contracting Manual are not required to obtain legal services through competitive bidding. Thus, we did not expect Irvine to go through a competitive process when obtaining special legal services for the park review.

Irvine retained two legal firms to assist with the park review. In March 2013, Irvine hired the firm of Jones & Mayer as the interim city attorney. While this firm was replaced later in the same year by another firm, Irvine chose to maintain Jones & Mayer as special counsel for the park review because the new city attorney declared that he had a conflict of interest related to the park review. Later in June 2014, Irvine replaced Jones & Mayer with another law firm—Aleshire. According to one of the subcommittee members, the subcommittee requested that the city manager hire a new special counsel for the park review because HSNO had stated that it had difficulty coordinating with Jones & Mayer’s representative and suggested to the subcommittee that it needed a different legal team to support its review efforts. The city manager explained that the subcommittee, along with the other city council members, had previously interviewed several law firms that applied to be city attorney during the recent solicitation for those services. He indicated that based on this experience, the subcommittee was quick to conclude that Aleshire would be well suited for the park review. Although the city could lawfully award a contract to Aleshire without competitive bidding, we raise questions in the next section about the approval and growth of the budget for that firm’s contract.

Finally, city staff stated that Irvine asked the two firms that provided legal services for the park review to subcontract with a private judge, a process the Joint Legislative Audit Committee requested we review. The contracts with its attorneys allowed for subcontracts with written city approval. According to Aleshire’s March 2015 report, the judge provided advice to special counsel on procedures used in the park review, took two depositions, and reviewed status reports and preliminary drafts. Table 1 in the Introduction shows that the retired judge received about $18,400 in total from both firms for her services.

Disjointed Contract Management Decreased Transparency Related to the Park Review’s Cost and Scope, and It Also Led to Cost Overruns

During the course of the park review, several actions by subcommittee members and staff undercut controls on contracts in the city’s procurement policies and procedures. Specifically, Irvine did not ensure that Aleshire adhered to its scope of work during the park review, which led to its duplicating the work of HSNO and producing a report that its contract did not require. Further, Irvine originally contracted with Aleshire for $30,000, an amount city staff had the authority to approve. However, when the value of Aleshire’s contract exceeded $100,000, city policies required that the city council approve the contract, but the contract did not come before the council for consideration. Also, in July 2014, city staff divided a $333,000 increase for the park review between HSNO and Aleshire, even though the council had not specifically directed staff to do so. These actions lacked transparency because Irvine did not make the public aware of how the city intended to use the funds or why the additional funds were necessary. Finally, both Aleshire and HSNO billed for work they claimed to have performed in advance of receiving city authorization to do so. When Irvine does not actively and effectively manage its contracts, it risks the possibility that—without key stakeholders’ knowledge—consultants will perform and receive payment for unnecessary work.

Irvine Did Not Ensure That Its Legal Counsel for the Park Review’s Second Phase Stayed Within Its Approved Scope of Work

Although the contract specified that Aleshire would act in a supportive role to HSNO, Irvine allowed Aleshire to take a lead role in conducting the second phase of the park review, a decision that ultimately led to Aleshire’s producing its own report that it was not contractually obligated to complete. In a city council meeting in July 2014, one member of the subcommittee stated that Aleshire would be taking the lead role in the second phase of the park review. In addition, the subcommittee members stated that they believed Aleshire was managing HSNO’s work, and the city manager acknowledged in email correspondence that Aleshire would provide primary audit leadership. However, the city council resolution in January 2014 initiating the second phase of the park review directed HSNO to perform the investigation and noted that special counsel would assist HSNO in its work by preparing and issuing subpoenas. The resolution further directed special counsel to assist the subcommittee. Moreover, when Aleshire took over as special counsel in June 2014, its contract directed it to facilitate HSNO’s work. Nevertheless, according to the assistant city manager, city staff directed Aleshire to review and approve HSNO’s invoices. Aleshire also presented on behalf of HSNO in certain city council meetings and in requests for increases to both Aleshire’s and HSNO’s budgets. In addition to HSNO’s presenting its final report in March 2015, Aleshire presented its own report even though its contract did not include a written report as a deliverable. By allowing Aleshire to operate beyond the stated scope of its contract, Irvine lost the ability to manage the work and it paid for unnecessary services.

Aleshire also duplicated HSNO’s work in several instances. For example, in one section of its March 2015 report pertaining to contract formation and administration, Aleshire concluded that from the beginning of the Great Park project, appropriate city requirements concerning bidding and sole‑source contracts were not followed consistently. This type of examination was a required element of HSNO’s scope of work and therefore duplicative. In multiple cases, the two reports covered the same ground: Both reports criticized the Great Park project for having excessive change orders, both criticized Irvine’s decision to hire the group of consultants charged with designing Great Park, and both criticized the lack of evidence for the amount of work a public relations firm performed. The two consultants also cited information about the inappropriate influences of one contractor and a former city council member on the project, and both criticized that same council member for underestimating the cost of Great Park.

Because Irvine did not ensure that Aleshire’s contract reflected the full scope of the services that the city allowed the consultant to perform, it further increased the risk that the firm would conduct unnecessary or unwanted work that was unknown to the full city council or the public. Although Aleshire’s contract did not mention producing a written report, it did allow Aleshire to draft documents, including subpoenas and opinions, as part of its work. However, the contract specifically included these allowances in the context of facilitating HSNO’s work, and it did not direct Aleshire to manage HSNO or to assume any of HSNO’s audit responsibilities under its scope of work. However as we mentioned previously, the members of the subcommittee stated that they believed the legal firm was managing HSNO. If Irvine had intended that Aleshire manage HSNO and that Aleshire would take the lead role and produce its own report on the park review, the city should have stated this intention explicitly in the contract with Aleshire.

The ability of Aleshire to exceed its scope of services was also a result of the disjointed approach that Irvine took in managing the consultant’s work. First, the city council did not reconcile the language in its resolution that directed the city manager and staff to cooperate with the subcommittee with provisions in the city charter and city ordinances that give the city manager a strong oversight role in all aspects of city administration. Because of that, the city council placed the city manager in a conflict; he had both a cooperative role, which implied taking direction from and heeding the direction of the subcommittee, and the stronger oversight role outlined in the city charter and ordinances. According to the city manager, he understood he was not to direct Aleshire and he did not recall making changes to Aleshire’s scope of services. He explained that the city council resolution directed him and his staff to cooperate fully with the investigation as overseen by the subcommittee, and this left no doubt as to who was leading the park review. In his view, the park review was exclusively the province of the subcommittee.

However, the two subcommittee members gave us conflicting answers when we asked them whether they were overseeing the park review. In particular, one member stated that the subcommittee’s function was to oversee the park review, while the other explained that the overall direction and work of the park review was determined by HSNO and Aleshire because the two consultants reviewed documentation, conducted interviews, and wrote the reports. Furthermore, the city’s contract with Aleshire specified that the city manager was the city representative responsible for Aleshire’s contract and he was to provide prior written approval for any tasks or services Aleshire performed outside of the scope of services. If Irvine had not intended for the city manager to be the primary manager for Aleshire, it should have ensured that the contract had a representative other than the city manager who could perform that function. This designation would have allowed Irvine to better manage the relationship between the two firms, to ensure that the public was informed about each firm’s role in the second phase of the park review, and to confirm that Aleshire’s work did not exceed the contract’s scope of services. Instead, the firms performed a substantial amount of overlapping work and came back to the city council several times for budget increases, ultimately leading to the city council’s refusal to pay for some work, as we describe in the next section.

Irvine Did Not Ensure That Consultants Performed Only Work That It Had Previously Authorized

HSNO and Aleshire both billed Irvine for work they stated they performed before they received formal authorization to do so. Irvine’s policies allow contractors to perform work only after the city issues a purchase order authorizing the expenditure of funds and only up to the purchase order’s limit. Additionally, both HSNO’s and Aleshire’s contracts stated that no work would be performed before the receipt of a signed purchase order. However, in some instances beginning in June 2014, both consultants billed beyond their authorized limits. By not managing and enforcing the terms of the contracts, Irvine risked its consultants performing unnecessary work. Additionally, the consultants risked performing work for which they would not be compensated.

HSNO billed Irvine for work beyond its authorized limit in June 2014. Specifically, as we explained earlier, the city council approved a $400,000 sole‑source contract for HSNO in January 2014, which Irvine funded by issuing a purchase order in early February 2014. According to its invoices, HSNO had performed $400,000 in work by early June 2014, more than a month before staff allocated additional funds for HSNO in late July 2014. Irvine issued a warning to HSNO in June stating that the firm was not authorized to perform work that exceeded $400,000 without city council approval, explaining that any work HSNO performed above its contract amount would be done at its own risk. Nevertheless, according to subsequent invoices, HSNO exceeded its $400,000 budget by $35,000 before receiving $78,000 in additional funds in July 2014 as part of a $333,000 appropriation that was split between HSNO and Aleshire. Irvine paid for the work that it had not previously authorized out of the new allocation.

Aleshire also billed Irvine for unauthorized services almost as soon as it began work on its contract for the park review. In mid‑June 2014, Irvine contracted with Aleshire for $30,000 to facilitate HSNO’s work on the second phase of the park review. However, according to its invoices, Aleshire had already performed roughly $30,000 in work by the date of the city’s purchase order funding the contract. Aleshire’s contract indicated that some work completed before execution of the contract would be considered within the scope of the contract, and according to the purchasing agent, Irvine needed Aleshire’s services quickly and there was not enough time to perform the normal process of issuing the contract and purchase order in advance of commencing work. Even though, according to its invoices, it had expended its original $30,000 contract amount, Aleshire continued working. Aleshire billed more than $77,000 beyond its initial authorization by the time it received additional spending authority of $255,000 at the end of July 2014 and had exceeded the July 2014 increase in spending authority by more than $119,000 as of December 2014.

Neither Aleshire nor HSNO adhered to the billing terms of their contracts, and Irvine did not enforce these terms, which contributed to the consultants’ abilities to work beyond the authorized amounts of their respective contracts. Although their contracts required monthly invoices within 15 days of the end of each month in which services had been provided, both firms submitted some of their invoices late. For example, in 2014 HSNO did not submit its invoice for July until September and Aleshire did not submit its invoice for June until August. Aleshire also waited until the end of March 2015, after the firm had completed its park review report, to submit an invoice for its work in October and November 2014. In addition to violating the terms of the contract, late invoices prevented Irvine from adequately monitoring these consultants to ensure that they were performing work as expected.

Additionally, confusion occurred over who was managing the consultants. According to the city manager, staff would ordinarily be able to order a consultant to stop work if the consultant was not authorized to perform that work. However, he explained in email correspondence with the subcommittee members that the park review presented unique challenges. For example, he noted that staff were subjects of the park review and would not be in an ideal position to review and approve these two consultants’ invoices, implying that there would be a conflict of interest for them to do so. To address this concern, Irvine staff created a process for the subcommittee members to review the consultants’ invoices. Further, according to the assistant city manager, Aleshire reviewed HSNO’s invoices before they were forwarded to the subcommittee for approval.

Although the subcommittee began receiving the consultants’ invoices in July 2014, the subcommittee was not managing the consultants’ budgets. According to city staff, the invoice approval process involving the subcommittee was intended to provide an extra level of review. However, the process did not require the subcommittee to approve the expenditures. Instead, staff informed the subcommittee that Irvine staff would go ahead and pay the invoices unless the subcommittee objected. According to the city manager, staff members chose to use this structure to ensure that they would still be able to pay the invoices in a timely fashion should the subcommittee members not promptly respond. However, the subcommittee was not able to review all of the invoices. Irvine did not receive some of the invoices for work performed during the existence of the subcommittee until after the city council had dissolved the subcommittee. Moreover, one of the two subcommittee members asserted that she did not review any of the invoices. Also, the assistant city manager told us that she did not recall ever receiving a response from the subcommittee regarding the invoices. Staff members were therefore able to pay the invoices without approval from the subcommittee, and this situation rendered the subcommittee’s review, if it took place at all, irrelevant.

Moreover, management of HSNO’s invoices was ineffective. Although Irvine tasked Aleshire with reviewing HSNO’s invoices, HSNO nevertheless continued to submit invoices late and continued to perform work beyond its spending authority. The lack of a specific manager who reviewed and approved invoices from both HSNO and Aleshire increased the risk of confusion regarding the review and approval process and made it difficult to determine who was responsible for overseeing the consultants. Both consultants continued to work beyond their authority to do so and ultimately performed work for which they were not compensated. By the end of June 2015, Aleshire had billed more than $200,000 beyond its authority, and HSNO had billed $67,000 beyond its authority. Subsequently, the city paid $5,000 for a legal opinion from a separate law firm to advise it regarding payment of those invoices. In the end, city staff recommended—and the city council approved—payment only to Aleshire, and only for approximately $56,000 for services that the city did not originally foresee or request. When Irvine allowed its contractors to perform work in advance of contract execution or other authorization and did not enforce the terms of their contracts, it incurred expenses it otherwise would not have needed to incur, such as the $5,000 legal opinion.

Irvine Did Not Obtain City Council Approval When It Authorized a High‑Value Contract for Special Counsel

A subsequent action by city staff caused the value of Aleshire’s services to rise above the threshold requiring city council approval. In July 2014, Irvine staff allocated $255,000 to Aleshire from funds the city council approved for the park review, even though the city council action did not specify an increase to Aleshire’s funding beyond $100,000. Staff issued a revised purchase order increasing Aleshire’s spending authority from $30,000 to $285,000. Because this amount increased the total value of Aleshire’s contract to more than $100,000, consistent with Irvine’s contracting policies and procedures, Aleshire’s contract should have come before the city council for approval, but it did not. The purchasing agent explained that because the contract did not specify a maximum amount and had no change to the scope of services or contract term, it did not require an amendment and the funding increase was authorized through a revised purchase order. However, we question this staff decision because Irvine’s policies do not explicitly allow for or prohibit this exception, and the decision resulted in a contract with Aleshire worth $285,000 at that time, a contract that had not been approved by the city council. Irvine’s policies require only staff approval for purchase orders, whereas an amended contract requires approval by specified city staff or by the city council based on the dollar amount of the contract. In this case, to be consistent with the intent of its policies and procedures, we believe the city council should have reviewed and approved a contract amendment because the increased budget for the contract’s value exceeded the threshold for city staff approval.

Further, Irvine did not adhere to an additional requirement for sole‑source contracts. Irvine policy requires that the city council authorize sole‑source contracts over $100,000. Policies specifically note that when a revised purchase order requires a higher level of approval, city staff must seek that approval. The purchasing agent told us that a sole‑source justification is ordinarily presented in a staff report accompanying the agenda item for city council action. However, according to the assistant city manager, the city council member who proposed the budget increase did not request that staff make such a report.

City staff was aware that they might need city council approval of the contract. Specifically, the city manager and assistant city manager stated that they presented two draft motions to the subcommittee member who requested the July 2014 budget increase. The first authorized the city manager to hire special counsel to assist the subcommittee, as well as specifying how much of a related budget increase would be allocated to the special counsel. The second only specified the recipients of the budget increase. According to the assistant city manager, the decision of city staff and the subcommittee member presenting the budget increase, which included consultation with counsel, was that neither of these explicit authorizations were necessary. The memo the subcommittee member submitted to propose the July 2014 budget increase did not include any documentation of Aleshire’s contract and, according to the city clerk and our review of city council meetings, the contract did not appear in any materials presented to the city council in 2014. Nevertheless, not seeking council approval for a high‑value contract is contrary to the spirit of Irvine’s policy requiring such approval. Irvine’s policy, if followed, ensures that the council is able to exercise its authority over the city’s spending decisions and ensures that such decisions are made in an open and transparent manner.

Allowing the city to approve high‑value contracts without public consideration by the city council limits transparency and suggests that staff and not the council made significant financial decisions without council or public scrutiny. Minimizing staff authority to engage in high‑value contracts ensures that the city council, the body ultimately responsible for the city’s finances, will be able to review such contracts before the city commits its funds. Although future increases in Aleshire’s contract received council approval, the council never approved the contract itself. Ultimately, Aleshire’s contract cost the city more than $600,000. In fact, in a June 2014 city council meeting, a subcommittee member confirmed that the subcommittee had selected Aleshire, and in the subsequent July city council meeting, two council members were critical about the fact that they did not have information or input into hiring Aleshire. Although we do not question the legality of the contract, city council approval would have increased transparency by requiring consideration of the contract in a public forum and would have provided city council members with relevant information for certain funding decisions, as we describe in the next section.

Irvine Increased the Budgets of the Two Consultants for the Park Review Without Adequate Explanation and Deprived the Public of Information About the Expenditure of Public Funds

Irvine divided an increase in funding for the park review between the two consultants—HSNO and Aleshire—without specific direction from the city council. In July 2014, the city council approved a budget increase of $333,000 to finalize the park review. Subsequently, in consultation with Aleshire and the subcommittee, city staff divided this appropriation, with Aleshire receiving $255,000 and HSNO receiving $78,000. However, neither the agenda nor the minutes from that city council meeting indicate that Irvine intended to split the appropriation. The submitted agenda item—a memo from one subcommittee member to the city manager—specifically requested a budget increase “to allow the Great Park auditor” to finalize the park review, and the memo specifically named HSNO as the auditing firm. Further, the official minutes of the meeting stated that the funds were for the Great Park auditor, and they specified HSNO. Thus, both the memo and the meeting minutes indicated that Irvine would provide the entire budget increase to HSNO. Based on our review of video of the meeting, the actual motion as spoken by a subcommittee member did not specify who was to receive the money from the budget increase. However, we noted that one subcommittee member stated during discussion on the motion that the money would be going to finalize the park review, including to the legal team. Although that subcommittee member acknowledged that funds would be provided to legal counsel, discussion did not take place regarding the amount legal counsel or HSNO would receive.

Of further concern is that city staff deferred to Aleshire on how to divide the council’s $333,000 budget increase for the park review. As noted already, the agenda for the July 2014 meeting in which the city council considered the increase included a memo from a subcommittee member requesting the increase; however, that memo contained no indication of the amount, did not justify how much or why additional work was required, and did not describe how such work was beyond what was previously contemplated. Although Aleshire spoke of needing $100,000 for design and construction experts to assist with the investigation, it did not justify to the city council the remainder of the budget increase for either itself or HSNO. Moreover, during a subsequent city council meeting, an attorney for Aleshire stated that the firm did not hire any outside experts; instead, it used the money for its own legal work such as taking depositions. After the council passed the budget increase, city staff stated in a memo to the subcommittee that Aleshire had asked them to allocate $78,000 to HSNO and $255,000 to Aleshire. The assistant city manager stated that because staff was not managing Aleshire’s work, staff did not know Aleshire’s work progress or how much funding it needed to complete its scope of work. The memo went on to state that staff would increase the consultants’ budgets as Aleshire had requested, resulting in Aleshire’s receipt of three‑quarters of the total increase in funding.

Irvine’s actions effectively meant that the city made a decision to increase the funding for these two consultants partially outside of the public eye. The lack of clarity in the city council’s agenda, minutes, and discussion during the council meeting prevented the public from fully knowing how the council intended to spend these public funds. Finally, by allowing one of its consultants to decide on both the amount of a budget increase and how that increase would be distributed without also providing clear justification for the expenses and the distribution, the council deprived the public of information regarding the extent of the work on the park review and cannot demonstrate that it paid only for necessary work that it had requested.

Creating an Unnecessary Park Review Subcommittee That Was Exempt From State Open Meeting Laws Compromised the Park Review’s Integrity

Because the subcommittee did not maintain any public documents regarding its activities and discussions, such as agendas or meeting minutes, Irvine cannot demonstrate to the public the extent to which the subcommittee adequately carried out its assigned tasks. State law exempts advisory committees, such as the subcommittee, from open meeting requirements, including the publishing of meeting dates and times and posting meeting agendas in advance. Both members of the subcommittee, as well as city staff, confirmed that they did not create agendas nor maintain official minutes of the subcommittee’s meetings. According to a memorandum from the then‑acting director of administrative services to a council member, the subcommittee met eight times before the issuance of HSNO’s January 2014 report. According to one of the subcommittee members, the subcommittee only met once between the hiring of Aleshire in June 2014 and the issuing of the second phase reports in March 2015. Irvine does not have documentation of the types of decisions, if any, the subcommittee made or the discussions that occurred. According to interviews we conducted of the subcommittee members and of selected city staff members as well as our review of minutes of city council meetings, we found no evidence that the subcommittee acted beyond its authority as an advisory committee, but equally important, we found little evidence that the subcommittee added value to the process.

Further, although the city council charged the subcommittee with overseeing the park review, Irvine contracted with outside law firms who, particularly during the second phase of the park review, undertook many of the oversight activities that the subcommittee should have performed. During the first phase of the park review, the subcommittee was to receive findings from HSNO and provide information to the city council. However, minutes of city council meetings indicate that the subcommittee did not report to the council during the first phase of the park review. During the second phase of the park review, the city council required the subcommittee to oversee the park review and ultimately to report to the full city council the results of the investigation. However, one subcommittee member stated that she understood Aleshire was the project manager over the park review because the contract indicated it was the project manager. Further, both subcommittee members stated that Aleshire was managing the work of HSNO. Nevertheless, as described previously, Irvine’s contract with Aleshire specified that it was to facilitate the work of HSNO, not manage the firm’s work.

We also found little evidence that the subcommittee advised the council. The role of an advisory body, in the context of open meeting laws, is generally described as counseling, suggesting, or advising. We expected to find evidence that the subcommittee, in accordance with its assigned responsibilities, had recommended to the city council that it consider taking certain actions regarding the park review, such as whom to subpoena, how much funding to provide to Aleshire and HSNO, and what objectives HSNO should be directed to investigate further. Although a memo from city staff to the city council indicates that the subcommittee participated in developing the initial RFP for the park review, there is no evidence in city council minutes that the subcommittee provided any advice to the council in 2013. In January 2014, the subcommittee did recommend to the city council that it authorize the second phase of the park review. However, subsequent to that meeting, proposals related to the second phase of the park review were not presented as recommendations by the subcommittee but as recommendations by either an individual city council member or Irvine’s special counsel for the park review.

According to available information, the subcommittee’s actions did not exceed the authority of an advisory committee; however, we believe the subcommittee was unnecessary and compromised the integrity of the park review process. The subcommittee members provided varied responses when we asked them why Irvine needed to conduct the park review using an advisory committee. One of the subcommittee members stated that the subcommittee’s purpose was to add authority to, and oversee, the park review. This member also stated that although city staff would normally take a lead role in a subcommittee, in this case they did not because city staff was among the subjects of the park review and would not be able to give dispassionate and unbiased guidance to the subcommittee about the park review. Nevertheless, Irvine contracted for two other reviews of Great Park that were published in 2009 and in 2012, as we discuss in the Introduction, without creating an advisory committee to oversee the reviews. Although these reviews were smaller in scope and cost compared to the park review, these previous reviews were similar in that they also required the input of Irvine’s staff. Further, the other subcommittee member explained that the subcommittee was able to provide historical perspective to the firms conducting the park review. However, we believe an advisory committee was not necessary to provide this perspective. Specifically, members of the city council could have provided such perspective either through formal city council meetings or in individual meetings with the firms. Finally, we found scant evidence that the subcommittee acted to oversee the park review.

Because the subcommittee did not have to operate openly, the city council created an appearance of a lack of transparency. For example, as we described previously, Irvine hired Aleshire without the city council’s approval. A subcommittee member announced Aleshire’s participation in the park review at a city council meeting, and later another two city council members questioned why the council was not consulted on the selection of the firm, stating that it was not an open process. Further, throughout the process, the city council took public testimony both in support of and in opposition to the park review. Some of those opposed called into question why the subcommittee was operating outside the public eye. This public perception of a lack of transparency, compounded by Irvine’s disjointed approach to managing the park review, raises concern regarding the independence of the park review and its credibility with the public. Irvine could have avoided some criticism of the park review had it chosen not to create a subcommittee and had instead conducted its deliberations and made its decisions about the park review at hearings of a standing committee or at the city council level, either of which is subject to state open meeting laws.

Irvine Could Have Better Handled Depositions, and It Released Preliminary Park Review Results Before a Key Election

During the second phase of the park review, Irvine issued subpoenas for both records and testimony from individuals involved with Great Park. However, Irvine could have established and followed better methods for handling and publishing documents resulting from those subpoenas. State law allows city councils to issue subpoenas requiring attendance of witnesses or production of documents for evidence or testimony in any action or proceeding pending before it. The law requires that subpoenas be signed by the mayor and attested to by the city clerk. Further, in January 2014, Irvine’s city council authorized the subcommittee to issue subpoenas in cooperation with the city’s attorney for the park review. We reviewed the 23 subpoenas the city issued related to the park review and noted they were appropriately executed.

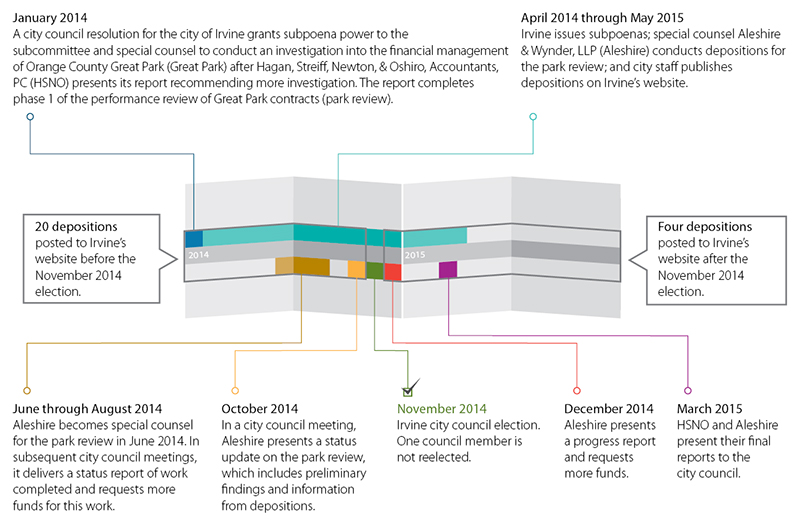

Finally, in fulfilling the Joint Legislative Audit Committee’s audit request, we reviewed whether discussions took place between the subcommittee and the park review consultants to time the public release of depositions or the park review reports to occur before the then‑upcoming November 2014 elections. In November 2014, Irvine voters voted on a measure to increase the transparency of Great Park’s development, to select a mayor, and to select two city council members. One of the incumbent council members on the ballot was a long‑time council member and a key player in the development of Great Park. Aleshire took—and Irvine posted publicly on its website—most of the depositions before the November election. However, four depositions occurred after the election, one of which—the deposition of the aforementioned incumbent city council member who was seeking reelection in November 2014—did not occur until March 2015. In addition, although the second phase of the park review was originally scheduled to end in August 2014 before the election, HSNO and Aleshire did not release their reports on the park review until March 2015. Both members of the subcommittee denied that there was any discussion related to timing the release of the reports or depositions. Further, we reviewed email and written correspondence and found no evidence of discussion of timing the release of reports or depositions to the election. Figure 3 is a timeline of the release of depositions and the reports related to the park review.

Figure 3

Timeline of the City of Irvine’s Depositions Related to the Orange County Great Park Review and to Irvine City Council Elections

Sources: The city of Irvine’s public records and the Orange County Registrar of Voters’ records.

Although we did not identify any evidence that discussions took place about timing the release of the depositions or reports with the election, we question whether the public release of some information was warranted. In a July 2014 city council meeting, a representative of Aleshire stated that it did not want to release findings until they were fully vetted. Regardless, in an October 2014 city council meeting, Aleshire reported on findings of its investigation while the investigation was still in progress. In that report, Aleshire alleged that a Great Park contractor modified some of its invoices to make it appear as though the contractor had provided more work than it had accomplished. Although Aleshire and HSNO both raised concerns regarding that contractor in their March 2015 reports, neither concluded whether the contractor modified any invoices. Aleshire noted in its March 2015 report that it had discussed preliminary findings with the city council in public meetings but stated that where the investigation was inconclusive, Aleshire withdrew its preliminary findings. Nevertheless, by allowing a public presentation of preliminary findings, the city council allowed Aleshire to discuss findings later found to be untrue or unsubstantiated. Further, by permitting Aleshire to publicly disclose these preliminary findings so close to the November 2014 election, the council created an opportunity to influence public opinion in advance of an election. In fact, in its March 2015 report, Aleshire suggested that the park review deserves some of the credit for passage of a ballot measure, mentioned earlier in this section, that increased transparency related to Great Park in November 2014.

Whistleblower Protections Exist for Those Who Report Improper Governmental Activities, and Irvine Recently Improved Its Processes for Receiving Complaints

Whistleblower laws at the state level and in Irvine protect individuals from retaliation by governmental agencies or employees when those individuals bring to light improper governmental activities. These protections extend to any employees, contractors, or members of the public who feel they have been retaliated against by Irvine for raising concerns about the park review. At the time of our review, we identified room for improvement within Irvine’s processes for receiving and investigating complaints about improper governmental activities. For instance, Irvine has established a hotline for suppliers, contractors, and consultants to report complaints, but it had not advertised the availability of this hotline to other key stakeholders, such as the residents of Irvine. Further, Irvine’s contract with the hotline provider had expired. After we brought these concerns to Irvine’s attention, it improved the way it publicized the hotline and updated its contract with the hotline provider.

State law encourages state employees and other persons to disclose any improper governmental activity by a governmental agency or employee that violates any state or federal law or regulations; that is wasteful; or that involves gross misconduct, incompetency, or inefficiency. State law also prohibits a governmental agency or employee from retaliating against those who disclose any improper governmental activity to a committee of the Legislature when the agency’s or employee’s response is to prevent or punish the disclosure. In its code of ordinances, Irvine maintains whistleblower protections similar to those in state law and extends these protections to any persons, including city officials or employees, who report inappropriate governmental activities, such as gross waste of city funds or abuse of authority. As part of a larger fiscal transparency and reform measure related to Great Park, Irvine voters approved in November 2014 a local proposition that specifically extended whistleblower protections to anyone, including a vendor or contractor, who reports an improper governmental activity related to Great Park. Thus, Irvine ordinances afford all whistleblowers protections against retaliation from the city, Great Park officials, and other city employees. These protections extend to those who raise concerns about the accuracy of the park review reports.

Additionally, individuals who feel they have been retaliated against by Irvine for reporting improper governmental activities can seek relief or redress from the city through the legal system. Several stakeholders publicly opposed or raised concerns about the process or results of the park review. To the extent any of these stakeholders believe that the park review constituted an improper governmental activity, such as a gross abuse of authority, and believe Irvine retaliated against them for raising such concerns, Irvine ordinances provide them with an opportunity to address retaliation through those ordinances. However, as of mid‑June 2016, the city manager stated that no one had taken legal action against Irvine related to retaliation.

An additional option for contractors to report improper governmental activities is through Irvine’s hotline. Specifically, this hotline, referred to as the integrity line, is publicized through Irvine’s guide for suppliers, contractors, and consultants doing business with the city. According to Irvine’s manager of human resources, the city processes whistleblower complaints related to Great Park in accordance with its Personnel Rules and Procedures and these procedures apply to complaints from both city staff and contractors. These procedures state that upon receiving a complaint, Irvine’s personnel officer will assign the appropriate individuals to conduct the investigation and, if necessary, to recommend any disciplinary action to the city manager, who makes the final determination regarding discipline. The manager of human resources stated that in the event of a complaint, the personnel officer may choose to contract the supervision of the investigation to an independent party. The city’s procedures also state that the identity of the individual filing the complaint will remain confidential to the fullest extent possible. However, when we reviewed the integrity line’s activity report for the 2015 calendar year, which is the only report Irvine could provide, it showed no activity or calls to the hotline for that period at all. In June 2016, Irvine’s manager of human resources confirmed that to her knowledge, the city had not received or investigated any whistleblower complaints or complaints of retaliation since HSNO released its first report in January 2014.