Introduction

Background

According to the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, research indicates that youth who are aging out of the child welfare system have lower educational achievement and more often struggle in their early adult years with issues such as homelessness, behavioral health disorders, unemployment, and criminal justice involvement than do youth without child welfare involvement. In addition, recent research on youth who are involved with both the child welfare system (dependency) and the juvenile justice system (delinquency) has demonstrated that these dually involved youth have even worse outcomes than youth without cross-system involvement.

Key Terminology as Used in This Report to Describe Dually Involved Youth

Dually Involved Youth—Youth who are involved with both the child welfare system (dependency) and the juvenile justice system (delinquency) regardless of whether the courts adjudicate them as dependents and wards simultaneously.

Dual Status Youth—Youth adjudicated simultaneously as a dependent child and a ward of the juvenile court.

Dependent Child of the Court—Youth who are under the primary responsibility of the dependency court because they have suffered—or there is a substantial risk they will suffer—abuse, neglect, or cruelty.

Ward of the Court—Youth who are under the primary responsibility of the delinquency court because they violated the law. If the delinquency court declares a youth a ward of the court, it may make orders for the care, supervision, custody, and support of the minor, including medical treatment.

Crossover Youth—Dependent youth who have had their dependency cases terminated after being adjudicated wards of the court.

Sources: Georgetown University Center for Juvenile Justice Reform’s Crossover Youth Practice Model, and Welfare and Institutions Code sections 241.1, 300, 602, 726, and 727.

Juvenile dependency cases generally start when counties receive reports indicating that children are at risk of neglect or abuse. After conducting investigations, child welfare service (CWS) agencies may file court petitions alleging actual or immediate danger to youth in their counties. If the safety of these youth cannot be assured at home, they can be removed from parental custody and placed in protective court custody. Judges may declare youth dependents of the juvenile dependency court when their homes are unfit because of abuse, neglect, or cruelty. County CWS agencies also provide a full array of social and health services that focus on the safety and well-being of dependent youth. The text box defines key terms that describe dually involved youth as used in this report.

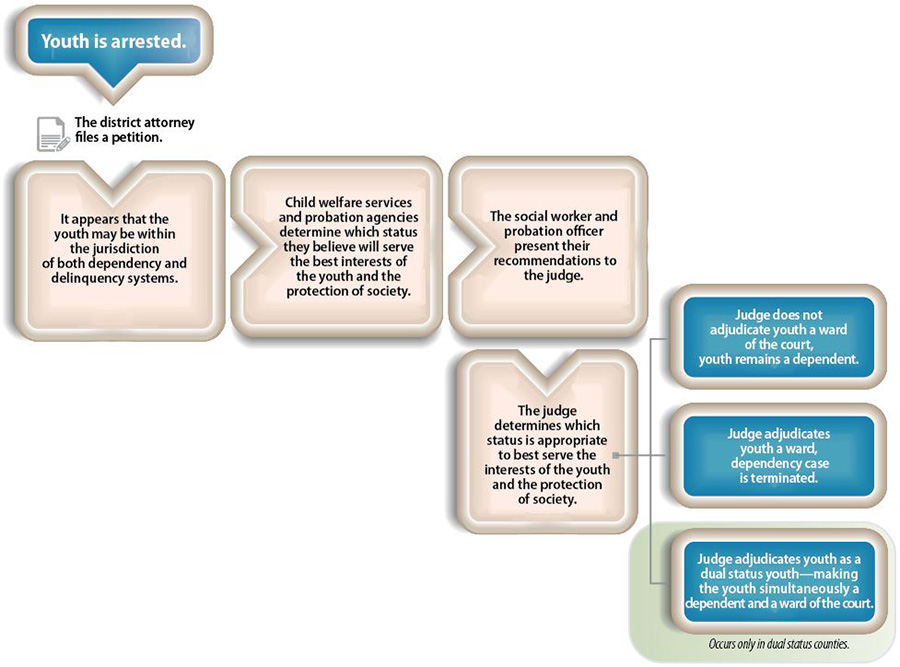

A youth's delinquency involvement may begin with a citation or when an officer arrests him or her. Juvenile delinquency cases generally begin when county district attorneys file petitions alleging that a youth has committed certain felonies, misdemeanors, or status offenses, such as truancy and curfew violations. At dispositional hearings, judges may declare the youth a ward of the juvenile delinquency court, allowing the court to make decisions about this youth in place of, or in addition to, his or her parents. The court may make decisions about the care, supervision, custody, conduct, and support of these youth, including medical treatment. County probation agencies (probation) enforce court orders, and may detain and provide services to those youth who are wards of the court. Depending on the county in which they live, when youth who are already dependents of the court are adjudicated wards of the court, they may either have their dependency case closed (crossover youth) or fall under the jurisdiction of both dependency and delinquency simultaneously (dual status youth). The text box defines certain key terms related to juvenile delinquency court proceedings, as used in this report.

Before 2005 state law required courts to determine which status was most appropriate for youth—dependency or delinquency; however, effective January 2005, the Legislature amended state law to grant each county the option of developing a dual status protocol that would permit the court to designate certain youth as dual status youth, i.e., simultaneously dependents and wards of the court. These dual status youth protocols are required to contain procedures to ensure both a seamless transition between dependency and wardship jurisdiction and a continuity of services. According to the bill analysis, before the law changed, California was one of only two states in the nation that did not use some form of dual status. As of February 2016, the Judicial Council reports that 18 counties have adopted dual status protocols. Six of these counties have populations greater than 1 million—the counties of Los Angeles, San Diego, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, and Santa Clara. Collectively, these 18 counties represent 67 percent of the state's population.

Key Terminology Used in Juvenile Delinquency Court

Sustained Petition—A petition is a document filed by the district attorney alleging that a youth committed an offense. A judge will sustain a petition if he or she finds the allegations against the youth to be true. A sustained petition is similar to a finding of guilt in an adult criminal proceeding. A dismissed petition is similar to finding an adult not guilty.

Adjudication—A judge’s determination as to whether a youth committed the charged offense. An adjudicated juvenile is akin to a convicted adult.

Disposition—The action to be taken or treatment plan decided on by the court. After the court sustains a petition, an adjudicated youth receives a disposition hearing and may be placed on probation and sent to a probation camp. If the judge determines the youth did not commit the charged offense, there will be no disposition hearing.

Sources: Legislative Analyst’s Office, California Courts, the United States Department of Justice, First District Appellate Project, and Santa Clara Superior Court websites.

Roles of Local and State Entities

County CWS and probation agencies have different roles when it comes to serving dually involved youth. The child welfare system provides social workers and a group of services that include emergency response, family maintenance and reunification, and permanent placement. These services are designed to promote the well-being and best interests of youth by ensuring their safety, strengthening families to care for their children successfully, and finding permanent homes for youth when necessary. CWS agencies contract for services with health care, mental health, substance abuse, and education programs to ensure that youth and their families receive effective assistance. CWS agencies can also provide services to the families of these youth through family maintenance or reunification plans. Similar to CWS agencies, probation agencies also have the responsibility to provide care and treatment consistent with the youth's best interests, and family preservation or family reunification services when appropriate. However, probation agencies also focus on rehabilitation of youth and the protection and safety of the public, and may consequently detain or incarcerate youth.

The State provides support to CWS and probation agencies as they serve dually involved youth. For example, the California Department of Social Services (Social Services) monitors and provides support to county CWS agencies through regulatory oversight, administration, and the development of program policies. Additionally, Social Services receives and distributes federal and state funding and oversees the operation of the statewide automated Child Welfare Services/Case Management System (statewide case management system). The statewide case management system is a tool all CWS and probation agencies can use to manage certain aspects of their cases. In establishing the statewide case management system, the Legislature intended to provide caseworkers a common database to effectively manage certain aspects of their cases. CWS and probation agencies can use this system for case management activities, service provision, and program management or documentation of case histories. For example, caseworkers can record client demographics, contacts, services delivered, and placement information. In addition, the legislation that allowed counties to develop dual status protocols required the Judicial Council of California (Judicial Council) to collect data and prepare an evaluation of counties' implementation of dual status protocols. However, this data collection requirement applied only to the two years following the State's first dual status case in 2005. The Judicial Council completed this evaluation and published its findings in a 2007 report. The report concluded that at the time of the study, counties were still in the formative stages of implementing their dual status protocols and that the Judicial Council could not yet assess the outcomes of dual status cases.

The Joint Assessment Process

Since 1990 state law has required each county's CWS and probation agencies to jointly develop written protocols (joint assessment protocols) to ensure appropriate local coordination in the assessment of youth who may fall within the jurisdiction of both the dependency and delinquency systems. Joint assessment protocols require consideration of the youth's prior involvement in either system, as well as his or her behavior, education, and home environment. Currently, whenever a youth appears to come within the description of both systems, state law requires social workers and probation officers to work together to make the initial determination of which status—dependency or delinquency—would best serve the needs of that youth and the protection of society. After determining the appropriate status for the youth, probation officers and social workers present their recommendation to the court for consideration. Before 2005 judges were only able to adjudicate youth as either dependents or wards of the court. Courts were prevented from making youth simultaneously both dependents and wards of the court.

Legal Requirements for Dual Status Protocols

According to state law, a county’s dual status protocols must include the following, among other things:

- A description of the process used to determine whether a youth is eligible for dual status consideration

- A description of the procedure the child welfare services and probation agencies will use to assess the need for dual supervision and the process to make joint recommendations to the court

- A provision for ensuring communication between juvenile court judges who oversee dependency and delinquency cases

- A decision of whether the county will use a lead agency or on-hold model. If the lead agency model is used, the protocol also needs a method for identifying which agency will be the lead

Source: Welfare and Institutions Code 241.1(e).

Beginning in 2005 state law allows county CWS and probation agencies, in consultation with the presiding judge of their juvenile court, to create dual status protocols. We refer to counties that do so as dual status counties. Juvenile court judges in dual status counties may declare a youth as dual status if the court deems it appropriate. However, even when a county has implemented a dual status protocol, its court can still adjudicate a dependent youth as a ward of the court and close his or her dependency case, similar to the process in a nondual status county. Figure 1 describes the typical process for adjudicating dually involved youth.

State law requires presiding judges of juvenile courts, chief probation officers, and CWS agency directors to sign the dual status protocols before declaring any youth as dual status in their counties. Dual status protocols must contain certain details about the county's dual status procedures, the key elements of which we describe in the text box. Counties that have dual status protocols can choose to adopt either a lead-agency model or an on-hold model. In counties that adopt a lead-agency model, the dual status protocols must include a method to identify which agency will be the lead agency. The lead agency will then be responsible for the youth's case management, court hearings, and court reports, but both the dependency and delinquency cases are still open to address the needs of the youth and his or her family. The on-hold model suspends the dependency case while the youth is a ward of the court. If it appears the court will soon terminate probation's jurisdiction but there is no safe home for that youth, the CWS and probation agencies jointly reassess the case and produce a recommendation to the court with regard to resuming the dependency case.

Figure 1

The Typical Process for Adjudicating Dually Involved Youth

Sources: Legislative Analyst's Office and Welfare and Institutions Code 241.1.

Funding Sources

The counties we visited—Alameda, Kern, Los Angeles, Riverside, Sacramento, and Santa Clara—receive a mix of federal, state, and local funding to cover their expenses related to child welfare and probation. For example, all of the counties receive federal Title IV-E funding to pay for foster care activities for eligible youth. In addition, all of the counties receive funding from the State, and the counties also use their general funds to cover additional costs. The counties we visited do not account for dually involved youth separately from other foster children or wards, but some counties have used private grants to help financ efforts specific to dually involved youth. For example, Sacramento County received $75,000 and Alameda County received $375,000 from the Sierra Health Foundation during our audit period for work related to the foundation's best practice model for dually involved youth. Similarly, the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation funded the National Council on Crime and Delinquency's delinquency prevention research project in Los Angeles County in 2013 through Georgetown University's best practice model.

Best Practices

We identified several best practice models for dually involved youth. These models aim to assist CWS and probation agencies in adopting practices and policies that better address the needs of dually involved youth. Four of the six counties we visited used one or more of the following three models during our audit period: Robert F. Kennedy Children's Action Corps-Juvenile Justice and Child Welfare System Coordination and Integration (Kennedy model), Georgetown University Crossover Youth Practice Model (Georgetown model), and Sierra Health Foundation's Positive Youth Justice Initiative (Sierra model). All three models recognize the importance of data collection, training, and cross-system cooperation.

The Kennedy model, established in 2004, promotes integration and cooperation between dependency and delinquency systems. Specifically, it provides guidance and technical assistance to agencies on developing a management structure, collecting and managing data, and establishing effective information-sharing guidelines. Santa Clara County began implementing this model in 2012.

The Georgetown model, established in 2007, addresses crossover youth by ensuring that CWS agencies work in coordination with the delinquency system to provide intensive services to address the needs and behaviors of youth. In addition, it advocates building on the strengths of youth and families to improve their lives and works with agencies in dual status and nondual status counties. Further, this model insists that both CWS and probation agencies use data to make all policy and practice decisions and that they must provide appropriate training to staff. Alameda County, Los Angeles County, and Sacramento County began implementing this model in 2013, 2010, and late 2014, respectively.

The Sierra model, established in 2012, is specific to the juvenile justice system. It supports California counties to transform their juvenile justice systems to improve the education, employment, social, and health outcomes of youth. The Sierra model's framework revolves around the idea that juvenile justice systems can better meet their public safety and rehabilitation goals by ensuring that their most vulnerable youth achieve the behavioral, mental health, educational, and pro-social outcomes associated with healthy transitions to adulthood. Sacramento and Alameda counties both received planning grants for the Sierra model in 2012. However, according to Sacramento County's assistant chief probation officer, the county dropped its implementation of this model after the initial grant planning phase and opted instead to consider the Georgetown model because the county felt that it offered more flexibility that better fit the county's needs. Alameda County received an implementation grantin addition to the planning grant, but according to the deputy chief of juvenile services, the county chose not to participate in the next phase because it was focused on education and the county was already working with other educational partners.

Scope and Methodology

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee (audit committee) directed the California State Auditor to conduct an audit to determine how well counties are addressing the needs of crossover youth, including those with dual status. We list the objectives that the audit committee approved and the methods we used to address them in Table 1.

| Audit Objective | Method | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Review and evaluate the laws, rules, and regulations significant to the audit objectives. | We reviewed relevant laws, rules, regulations, and other background materials. |

| 2 | For a selection of six counties (three nondual status counties, one lead agency county, one county using the on-hold model for at least some of its cases, and Los Angeles County), compare the services provided to foster youth over the past three years who either were deemed to have dual status in the dependency and delinquency systems or had their dependency cases closed as a result of an open delinquency case (crossover youth). The comparison of services should include the county agency's case management efforts to secure special education planning (if applicable) and health care services, including mental health counseling, as well as the extent of the agency's permanency planning efforts. | For all six counties:

For the cases selected:

|

| 3 | At the same selection of six counties as above, and to the extent possible, compare outcomes for crossover youth including, but not limited to, the following: | For the youth selected above: |

a. Convictions and sentences for juvenile offenses b. Extent and length of time of criminal justice involvement |

|

|

| c. Recidivism rates |

|

|

| d. Rates of re-entry into foster care |

Of the 166 youth we tested, only 18 met this criteria, and only one of these reentered foster care. |

|

| e. Number and types of placements |

|

|

| f. Graduation rates from high school or its equivalent |

|

|

| 4 | For the three dual status counties selected, examine the following: | For the three dual status counties: |

| a. How effectively the CWS and probation agencies, as well as juvenile justice courts and attorneys, are working together to meet the needs of crossover youth. Describe how these integrated partners maintain confidentiality while still effectively communicating needed information. |

These documents, in addition to provisions within state law, allow designated individuals, including CWS and probation staff, as well as juvenile justice courts and attorneys, access to a youth's case files. |

|

| b. How well these three counties collect data on crossover youth. |

|

|

| c. How often and under what conditions foster youth are deemed to have dual status. |

|

|

| d. What guidelines the three dual status counties are using and whether these guidelines are consistent with best practices used nationally. |

The counties' dual status protocols aligned with the guidelines of the best practice models related to collaboration between CWS and probation agencies. However, the best practice models were generally more exhaustive in their guidance, advocating for data collection and training, for example. |

|

| e. The extent to which they have established and adhered to timelines for crossover youth's dual status determinations, reunification with their families, and/or efforts to ensure a more permanent placement for these children. |

Only Los Angeles County had developed timelines related to dual status determinations. However, we found that court-established deadlines superseeded the county timelines.

Of the 166 cases we reviewed, we found five cases that did not meet reunification or permanency placement hearing timelines. |

|

| f. The continuity of dependency services, including maintaining the same court appointed special advocate, dependency attorney, and social worker. |

|

|

| 5 | Ascertain why the three nondual status counties selected have chosen not to undertake dual status protocols. | Interviewed key CWS and probation agency management to:

|

| 6 | At the six selected counties, compare the training and management oversight social workers and applicable probation officers receive related to crossover youth, as well as any differences in funding that may be affecting the services that crossover youth receive. |

|

| 7 | Determine what progress has been made regarding the following concerns raised by the Judicial Council report required by Assembly Bill 129: |

|

| a. Lack of communication and collaboration between agencies regarding specific responsibilities. | For the three dual county status counties:

We found that all of the counties we visited have established procedures to facilitate effective communication and collaboration between their CWS and probation agencies. |

|

| b. Misunderstanding and lack of knowledge among various participants in the dependency and delinquency systems. |

Although we noted a few anecdotes in which CWS and probation staff stated that misunderstandings still exist between the two agencies, we did not find sufficient evidence to indicate that this is a significant continuing issue. |

|

| c. Lack of guidance from state-level agencies and the need for additional training on how dual status protocols should be implemented. |

We determined that both Social Services and the Judicial Council have fulfilled their legal responsibilities. |

|

| 8 | Review and assess any other issues that are significant to the audit. | We did not identify any other significant issues. |

Sources: California State Auditor analysis of Joint Legislative Audit Committee audit request number 2015-115, and analysis of information and documentation identified in the table column titled Method.

Assessment of Data Reliability

In performing this audit, we obtained electronic data files extracted from the information systems listed in Table 2. The U.S. Government Accountability Office, whose standards we are statutorily required to follow, requires us to assess the sufficiency and appropriateness of computer-processed information that we use to support our findings, conclusions, or recommendations. Table 2 describes the analyses we conducted using data from these information systems, our methodology for testing them, and the conclusions we reached as to the reliability of the data. Although these determinations may affect the precision of the numbers we present, there is sufficient evidence in total to support our audit findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

| Information System | Purpose | Method and Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| California Department of Social Services (Social Services) Child Welfare Services/Case Management System (statewide case management system) Child welfare services case file data for the period of January 2012 through December 2014. |

To determine the number of cases with joint assessment hearings that occurred between January 2012 and December 2014. | We performed data-set verification procedures and did not identify any issues. We reviewed existing information to determine what is already known about the data, and found that prior audit results indicate there are pervasive weaknesses in Social Services' general controls. | Not sufficiently reliable for the purpose of this audit. Although these determinations may affect the precision of the numbers we present, there is sufficient evidence in total to support our audit findings, conclusions, and recommendations. |

| Alameda County Probation Department 241.1 database Joint assessment hearing data for the period of January 2012 through December 2014. |

To make a selection of 30 youth who had joint assessment hearings at which the court terminated the youth's dependency cases and adjudicated them as wards of the court. | The purpose for which we used the data did not require a data reliability assessment. However, we attempted to validate the completeness of the universe from which we made our selection of youth. We performed data-set verification procedures and did not identify any issues. To verify the completeness of Alameda County's joint assessment hearing data, we attempted to reconcile the total number of hearings reported in its 241.1 database to those recorded in Social Services' statewide case management system. We determined that the two data systems could not be materially reconciled. In addition, we reviewed the date and hearing results for a random selection of 29 youth's joint assessment hearings. We determined that Alameda County inaccurately recorded the hearing dates for two youth, and it did not record the hearing results for any of the 29 youth we reviewed. |

Not complete for the purpose of this audit. Because no other source of this data exists, we made our selection of youth from this data system. |

| Kern County Probation Department Criminal Justice Information System Joint assessment hearing data for the period of January 2012 through December 2014. |

To make a selection of 30 youth who had joint assessment hearings at which the court terminated the youth's dependency cases and adjudicated them as wards of the court. | The purpose for which we used the data did not require a data reliability assessment. However, we attempted to validate the completeness of the universe from which we made our selection of youth. We performed data-set verification procedures and did not identify any issues. To verify the completeness of Kern County's joint assessment hearing data, we attempted to reconcile the total number of hearings reported in its Criminal Justice Information System to those recorded in Social Services' statewide case management system. We determined that the two data systems could not be materially reconciled. In addition, we determined that the county did not use the system to record the hearing results for any of the youth. Although the county manually compiled the hearing results of these youth, our review of a random selection of 29 youth's joint assessment hearings revealed that the county inaccurately recorded the hearing results for one of the youth. In addition, we found five crossover youth were missing from Kern County's list of joint assessment hearings. For example, in one case, Kern County did not include a youth who had a joint assessment hearing and was declared a ward of the court. |

Not complete for the purpose of this audit. Because no other source of this data exists, we made our selection of youth from this data system. |

| Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services 241.1 Web Application Joint assessment hearing data for the period of January 2012 through December 2014. |

To make a selection of 30 youth who had joint assessment hearings at which the court adjudicated them as dual status youth. | The purpose for which we used the data did not require a data reliability assessment. However, we attempted to validate the completeness of the universe from which we made our selection of youth. We performed data-set verification procedures and did not identify any issues. To verify the completeness of Los Angeles County's joint assessment hearing data, we attempted to reconcile the total number of hearings reported in its 241.1 Web Application to those recorded in Social Services' statewide case management system. We determined that the two data systems could not be materially reconciled. In addition, we reviewed the date and hearing results for a random selection of 29 youth's joint assessment hearings. We determined that Los Angeles County inaccurately recorded the hearing dates or results for six of the 29 youth we reviewed. |

Not complete for the purposenof this audit. Because no other source of this data exists, we made our selection of youth from this data system. |

| Riverside County Probation Department Juvenile and Adult Management System Joint assessment hearing data for the period of January 2012 through December 2014. |

To make a selection of 30 youth who had joint assessment hearings at which the court adjudicated them as dual status youth. | The purpose for which we used the data did not require a data reliability assessment. However, we attempted to validate the completeness of the universe from which we made our selection of youth. We performed data-set verification procedures and did not identify any issues. To verify the completeness of Riverside County's joint assessment hearing data, we attempted to reconcile the total number of hearings reported in its Juvenile and Adult Management System to those recorded in Social Services' statewide case management system. We determined that the two data systems could not be materially reconciled. In addition, we asked Riverside County's child welfare services (CWS) agency to verify the probation department's list of unique youth who became dual status during our audit period against its own records after we found a number of errors in probation's list. This process reduced the probation department's list from 212 to 115 unique youth. Moreover, we reviewed the date and hearing results for select youth in the resulting list and found that Riverside County had inaccurately recorded the dates for five of the dual status youth's joint assessment hearings. |

Not complete for the purpose of this audit. Because no other source of this data exists, we made our selection of youth from this data system. |

| Sacramento County Probation Department Person Information Program Joint assessment hearing data for the period of January 2012 through December 2014. |

To make a selection of 30 youth who had joint assessment hearings at which the court terminated the youth's dependency cases and adjudicated them as wards of the court. | The purpose for which we used the data did not require a data reliability assessment. However, we attempted to validate the completeness of the universe from which we made our selection of youth. To verify the completeness of Sacramento County's joint assessment hearing data, we attempted to reconcile the total number of hearings reported in its Person Information Program to those recorded in Social Services' statewide case management system. However, Sacramento County was unable to identify the number of joint assessment hearings that occurred during our audit period because its CWS and probation agencies' data systems do not actively track this information. As a result, Sacramento County's CWS and probation staff had to rely on a list of potential crossover youth obtained from Social Services' statewide case management system and manually review case files within its Person Information Program to identify which youth had actually crossed over. The county ultimately identified 64 crossover youths whose dependency cases were closed during our audit period. |

Not complete for the purpose of this audit. Because no other source of this data exists, we made our selection of youth from this population. |

| Santa Clara County Dually Involved Youth Unit 241.1 liaison's spreadsheet Joint assessment hearing data for the period of January 2012 through December 2014. |

To make a selection of 30 youth who had joint assessment hearings at which the court adjudicated them as dual status youth. | The purpose for which we used the data did not require a data reliability assessment. However, we attempted to validate the completeness of the universe from which we made our selection of youth. We performed data-set verification procedures and did not identify any issues. To verify the completeness of Santa Clara County's joint assessment hearing data, we attempted to reconcile the total number of hearings reported in its 241.1 liaison's spreadsheet to those recorded in Social Services' statewide case management system. We determined that the two data systems could not be materially reconciled. In addition, we compared the date and hearing results for a random selection of 29 youth's joint assessment hearings from the 241.1 liaison's spreadsheet with the county's records and found that the county inaccurately recorded the hearing date for one of the youth. |

We were unable to determine whether the universe from which we made our selection was complete. Because no other source of this data exists, we made our selection of youth from this population. |

Sources: California State Auditor's analysis of various documents, interviews, and data obtained from the California Department of Social Services and the counties of Alameda, Kern, Los Angeles, Riverside, Sacramento, and Santa Clara.