Audit Results

A Lack of State Guidance Has Limited the State’s and Counties’ Ability to Assess the Outcomes of Dually Involved Youth

Since the initial implementation of dual status protocols in 2005, state level agencies have provided limited guidance to county agencies regarding youth who are involved in both the child welfare system and juvenile justice system (dually involved youth) because state law does not require them to do so. As a result, counties have used their own discretion in determining the degree to which they track the population and outcomes of these youth. For example, the three dual status counties—Los Angeles, Riverside, and Santa Clara—and three nondual status counties—Alameda, Kern, and Sacramento—we reviewed have not generally monitored outcomes to assess the effectiveness of their efforts on behalf of this population because they are not required to do so. In addition, most of the counties had significant problems identifying their population of dually involved youth when we asked them to provide such a list. This inability prevents the State and counties from effectively monitoring the outcomes of these youth. Despite these issues, four of the counties we visited have taken additional steps directly aimed at improving their programs that serve dually involved youth.

The State Provides Counties With Limited Guidance and Resources for Tracking and Comparing the Outcomes of Dually Involved Youth

Although the California Department of Social Services (Social Services) interacts to some extent with county child welfare services (CWS) and probation agencies on issues related to the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, it has provided them limited guidance specific to dually involved youth. The ability of Social Services to oversee the counties’ efforts is limited because dually involved youth are served by multiple systems and it has not been given the responsibility of overseeing the county agencies’ efforts to serve these youth. Although Social Services oversees county CWS agencies, it does not have the authority to require county probation agencies to collect data related to dually involved youth.

Similarly, state law initially required the Judicial Council of California (Judicial Council), which is responsible for creating rules of court that litigants in juvenile court must follow, to collect data and prepare an evaluation of the counties’ implementation of dual status protocols. However, this data collection requirement applied to only the two years following the State’s first dual status case in 2005. The Judicial Council completed its evaluation and published its findings in a 2007 report. Counties are no longer required to submit their protocols to the Judicial Council, and the Judicial Council is no longer required to review them. Thus, the Judicial Council is no longer required to assess whether counties have appropriately addressed the need for data collection within their dual status protocols. However, the Judicial Council established, by rule of court, a Family and Juvenile Law Advisory Committee that makes recommendations for improving the administration of justice in all cases involving marriage, family, or children, including issues affecting dually involved youth. Therefore, we believe that the Judicial Council is best positioned for facilitating discussions between state and county level stakeholders.

Nevertheless, the Judicial Council voluntarily provides counties with assistance, even though it is not legally required to do so and does not receive any funding for such efforts. According to a supervising attorney at the Judicial Council, the Judicial Council has provided case by case assistance to counties who were thinking about developing dual status protocols. For example, until 2010, the Judicial Council led regular conference calls to address questions that counties had about developing or implementing dual status protocols. The supervising attorney stated, however, that the Judicial Council discontinued the conference calls because of staffing issues and a lack of interest from local courts and justice partners. Additionally, in 2014 the Judicial Council worked with Santa Clara County when it was considering transitioning from an on hold dual status model to a lead agency dual status model. The Judicial Council provides assistance only to those counties that actively seek its support, thus some counties may be unaware of this resource.

Because the State has not defined key terms or established outcomes to track related to dually involved youth, it cannot monitor the outcomes for this population statewide. Specifically, the counties we visited had varying definitions for recidivism and reunification.2 This prevents the State from being able to compare outcomes in these areas across counties. The six counties we visited have different definitions for recidivism based on the period when the subsequent offense occurs, as well as the severity of the offense. For example, county definitions of the recidivism period include the youth’s probationary period, the six month period following the youth’s disposition, and the three year period following the youth’s first entry into probation. Further, county definitions of recidivism events differ; some count new sustained violations of probation while others count only new citations and arrests. In July 2011, the Chief Probation Officers of California—a professional association—adopted a universal definition of recidivism as a subsequent criminal adjudication/conviction while on probation supervision. However, our review found that not all of the counties used this definition. Until the State establishes standard definitions, the outcomes counties decide to track are not likely to be comparable.

Social Services provided counties with some guidance pertaining to dually involved youth in 2006, when it last published an All County Information Notice (information notice) regarding dual status protocols. That information notice provided CWS and probation agencies guidance on funding eligibility and programmatic issues, and it noted the need for system upgrades, but it did not provide guidance about how to track data for dually involved youth in the State’s Child Welfare Services/Case Management System (statewide case management system). The information notice stated that Social Services would improve the statewide case management system to address limitations and that it would provide instructions at a later date on documenting dual status cases. Although Social Services updated the system in 2010 to allow probation agencies to access the statewide case management system, it never provided instructions on documenting dual status cases. According to a policy analyst in Social Services’ Concurrent Planning Policy Unit, Social Services did not follow up on this matter because it encountered unforeseen technological issues after the information notice was issued. Nevertheless, Social Services could have improved the statewide case management system to identify and track specific child welfare information, such as youth who are declared dual status.

Best Practice Models Advocate Tracking the Following Information on Dually Involved Youth

- The number and percentage of youth who become dually involved

- The circumstances in which youth become dually involved

- Demographic information

- Information related to youths'

- Delinquent activities, including number of arrests and rates of recidivism

- Placements

- History of maltreatment

Sources: Georgetown University Center for Juvenile Justice Reform’s Crossover Youth Practice Model, and Robert F. Kennedy Children's Action Corps' Models for Change program.

Various national best practice models suggest that agencies start by designing and implementing uniform data collection and reporting systems, identifying their population of dually involved youth, and then beginning to track certain attributes and outcomes, which we present in the text box. Social Services is able to create special project codes within the statewide case management system that are designed to identify and track specific child welfare information. Nevertheless, it has not developed project codes that are specific to dually involved youth, even though establishing such codes within the statewide case management system would provide a readily available mechanism for the State and counties to identify the population of dually involved youth. According to Social Services’ Permanency Policy Bureau Chief (bureau chief), Social Services can create and implement optional or mandatory special project codes statewide. However, the bureau chief told us that for Social Services to implement special project codes that are mandatory for the counties to use, the State must sanction the change through statute, and reimburse counties for any resulting increase in mandated county workload. Social Services also stated that it is in the process of creating a new statewide case management system incrementally over the next five years. A manager on the project to replace the legacy system stated that the new system could allow counties to track dually involved youth, most likely without the use of special project codes. He said that the Legislature would still need to sanction a requirement for counties to record data on dually involved youth and that this would involve reimbursement of county costs. He expects that a module capable of identifying and tracking dually involved youth will be phased in by the end of fiscal year 2019–20. Nevertheless, because county staff already use the statewide case management system to manage certain aspects of their cases, we do not believe implementing this change would result in a significant additional cost.

Further exacerbating these problems is the fact that the counties’ data systems lack a common identifier, such as a social security number, which could be used to reconcile data that CWS and probation agencies record or to link information on youth who transfer between counties. According to Sacramento County probation’s senior information technology analyst, probation officers are not required to obtain a youth’s social security number, so this information is not always recorded. She further explained that probation officers encounter many youth who do not know their social security number, refuse to provide it, or may not even have one. As a result, county staff may try to rely on other information to identify youth across agencies, even though these data may be prone to error. Because CWS and probation agencies statewide are unable to reconcile their data systems, they cannot accurately identify their population of dually involved youth or readily track this population’s outcomes.

The State and Counties Cannot Track Outcomes Specific to Dually Involved Youth

The State has not identified key outcomes for dually involved youth, so most of the counties we visited have not tracked outcomes or established baselines to assess the effectiveness of their efforts related to this population. Although the counties report certain outcomes to receive federal funding, the counties typically track these outcomes for their entire population of dependents or wards. In general, county CWS and probation agencies reported that they track outcomes related to child safety, permanency, reduced out of home care, juvenile justice involvement and child well being. These outcomes, however, relate to the counties’ entire populations of youth who require CWS or probation services and are not tracked separately for dually involved youth. Similarly, Sacramento County’s probation agency tracks outcomes related to recidivism for its entire population of youth who are involved in the juvenile justice system, but does not separately track this information for dually involved youth. As a result, the tracked outcomes for probation may include youth who never had a dependency case. Moreover, Sacramento County’s probation agency uses a definition of recidivism that is different from other counties’ probation agencies, as previously mentioned. Thus, counties must be able to identify their population of dually involved youth and use standardized definitions before they can use these tracked outcomes to assess the effectiveness of their efforts in serving this population.

Most of the six counties we reviewed also could not accurately identify those youth who have had their dependency cases terminated after being adjudicated wards of the court (crossover youth) or those youth who have been adjudicated as both dependents and wards of the court (dual status youth). Specifically, we found that five counties could not accurately or completely identify the dates or results of joint assessment hearings, at which judges determine whether to place dually involved youth within the jurisdiction of the county welfare or juvenile justice system. Without this information, the counties cannot identify their population of dually involved youth, and the State cannot determine whether dual status counties subject dependents of the court to the juvenile justice system less frequently than nondual status counties. Although Social Services provides text fields in which counties’ CWS staff can track the results of joint assessment hearings within its statewide case management system, counties are not required to enter hearing information into these fields. All the counties we reviewed used these fields to some extent; however, their entries were often inconsistent or incomplete. As a result, most of the counties we reviewed had to rely on their own data systems, instead of the statewide case management system, to identify their crossover or dual status youth when we asked them for this information. Disparities between the State’s and counties’ records of joint assessment hearings, as shown in Table 3 below, underscore a statewide problem in reliably identifying this population.

| Child Welfare Services / Case Management System (Statewide Case Management System) |

County Databases | |

|---|---|---|

| County | Number of Cases With Joint Assessment Hearings |

Number of Cases With Joint Assessment Hearings |

| Nondual Status | ||

| Alameda | 187 | 145 |

| Kern | 11 | 111 |

| Sacramento | 49 | Not Available* |

| Dual Status | ||

| Los Angeles | 1,829 | 2,450 |

| Riverside | 256 | 212 |

| Santa Clara | 133 | 257 |

Sources: California Department of Social Services’ statewide case management system and various databases used by the counties of Alameda, Kern, Los Angeles, Riverside, Sacramento, and Santa Clara.

Note: In general, these data systems were not complete for the purposes of this audit. For additional detail, see Table 2, Methods Used to Assess Data Reliability, earlier in the report.

* Sacramento County’s probation agency could not create a list of joint assessment hearings that occurred between January 2012 and December 2014 because it does not track sufficient information related to these hearings.

We noted that the counties of Alameda, Kern, and Sacramento could not accurately determine the total number of cases with joint assessment hearings or the results of those hearings because they did not always track this information. As a result, these three counties could not accurately identify their population of crossover youth and dual status youth. We identified errors in the counties’ lists, in which Alameda identified 48, Kern County identified 73, and Sacramento identified 57 crossover youth who were adjudicated between January 2012 and December 2014. Although the counties of Los Angeles and Riverside had data systems that contain the dates and results of joint assessment hearings, we noted that these data systems also had inaccurate or incomplete information, thus preventing them from identifying their entire population of dually involved youth. According to the lists they provided, Los Angeles identified 793 and Riverside identified 115 dual status youth who were adjudicated between January 2012 and December 2014. The actual population of these youth is unknown because the counties are not required to maintain accurate and complete data on the outcome of joint assessment hearings. As a result, any observations on how frequently the hearings result in youth’s formal involvement with the juvenile system might be reflective of errors, rather than differences in the counties’ processes. Thus, the State cannot perform a robust comparison between the population of dually involved youth in dual status and nondual status counties.

Of the six counties we reviewed, Santa Clara was the only county that did not miscategorize the dually involved youth we tested. This happened because Santa Clara County has established its own system for logging all joint assessment hearings and the results of those hearings. Of the 257 joint assessment hearings recorded, 16 hearings resulted in the youth being declared dual status youth. According to Santa Clara’s dually involved youth liaison, the county relies upon its own system more often than the statewide case management system because its own system is more readily available, contains more detailed court hearing data, and has additional functionality. For example, Santa Clara’s system tracks notes that the dually involved youth liaison takes during each hearing, and allows staff to cross reference data and identify specific data trends. Nevertheless, Santa Clara County did not begin tracking outcomes for this population until July 2014.

The counties we visited explained that tracking certain outcomes for dually involved youth was difficult due to the nature of the cases. For example, none of the six counties we visited track high school graduation rates for their entire population of dually involved youth. According to Sacramento County probation’s human services program planner, the county’s probation agency does not have complete graduation data in its system, and the County Office of Education may not have information on youth who transfer to private schools and out of state schools that are not part of the statewide student database. In addition, Kern County’s probation division director stated that once a youth’s probation case is terminated, the agency no longer has the authority to track information related to that youth. Because the counties are not always able to track graduation information for their dually involved youth, they cannot determine whether they successfully met this critical educational goal.

Moreover, the State cannot compare some outcomes across counties because counties do not use the statewide case management system consistently. For example, we noted that probation officers in two counties recorded inaccurate data within the statewide case management system during our audit period. Specifically, probation officers in Alameda and Sacramento counties recorded in the statewide case management system that family reunification was the case plan goal for several youth; however, court records, which contain the actual case plan goal, indicated that the counties were not actually working towards reunifying these youth. Instead, the court had set different goals for these youth, such as emancipation or permanent placement. According to the division chief of Sacramento County’s probation agency, the agency has trained its clerical staff to select family reunification as the case plan goal when initially inputting youth’s information into the statewide case management system, even though the actual case plan may end up with a different goal. Similarly, Alameda County’s probation division director explained that its court clerks input family reunification as the case plan goal when its court orders a youth to out of home placement. Further, Alameda’s placement unit supervisor stated that the delinquency court judge does not order family reunification specifically. She explained that when the judge orders out of home placement, the probation officers will automatically look for family members with whom to reunify the youth as a first option. Although the State’s primary goal is to reunify a youth with his or her family, when appropriate, it is essential for county staff to accurately record and update the youth’s case plan goal in the statewide case management system so that information on goals and outcomes can be compared across counties.

Some Counties Have Recently Taken Steps to Improve Their Processes for Serving Dually Involved Youth

Despite limited state guidance, four of the counties we visited are in the process of implementing best practice models, which emphasize using data to make policy and practice decisions and providing additional training to staff. The counties of Alameda, Los Angeles, Sacramento, and Santa Clara are taking steps to monitor outcomes for dually involved youth. For example, in 2013 Los Angeles began tracking some information for its dually involved youth, such as mental health and substance abuse services received, new arrests, and educational status. Nevertheless, so far Los Angeles has tracked outcomes only for a subset of its dually involved youth as part of its research collaboration with California State University, Los Angeles. For example, Los Angeles County tracked the arrests of 11 dual status youth, which represents roughly 1 percent of the county’s estimated population of dual status youth. However, this effort is a first step in providing the county’s executive management with the information necessary to monitor the effectiveness of its efforts to serve these youth.

The other three counties have made less progress than Los Angeles County because they have only recently started implementing the data tracking aspect of the best practice models. For example, Santa Clara began its data tracking efforts in 2014. Its current efforts monitor type of placement, mental health and substance abuse services received, and arrests and sustained petitions, among other outcomes. Additionally, rather than tracking the outcomes only for yes or no type questions, Santa Clara’s database is designed to measure incremental changes. For example, instead of tracking whether or not the youth was enrolled in school, the desired measure tracks the number of eligible school days in the last semester compared to the number of days the youth attended. However this monitoring is limited to youth assigned to the county’s dually involved youth unit—a relatively small portion of its total dually involved youth population. The counties of Alameda and Sacramento have started implementing best practice models more recently than Santa Clara, and as a result, they are only in the initial planning stages of identifying the data they would like to monitor. According to the assistant director of Alameda’s CWS agency, data tracking will be discussed as part of its implementation efforts for the Georgetown University Crossover Youth Practice Model in the coming year. Similarly, Sacramento County’s human services program planner stated that the county’s CWS and probation agencies formed a committee in April 2015 with representatives from the Sacramento County Office of Education and Sacramento County’s Behavioral Health Services. She explained that the committee is working to create a system that will integrate and provide reports on data from all four agencies’ data systems.

Even though some counties did not implement best practice models, all of the counties we visited provided training to their CWS and probation staff related to dually involved youth. Specifically, all of the counties provided training either on the joint assessment process or on county specific procedures for capturing data related to dually involved youth. In addition, we noted that all three dual status counties and two of the nondual status counties we visited provided cross training between their CWS and probation staff on topics related to dually involved youth. Although Kern County, the third nondual status county, did not provide such specific cross training for dually involved youth, the assistant director of Kern County’s CWS agency stated that CWS staff have provided training to probation staff on topics related to placement services.

The Model That Counties Chose to Use in Serving Dually Involved Youth Did Not Appear to Greatly Affect the Outcomes and Services for This Population

Although the counties we visited did little to monitor the outcomes for dually involved youth, our review of 166 case files from across the counties indicated that dual status youth in dual status counties performed somewhat better than crossover youth in nondual status counties for some outcomes, while nondual status counties performed equally well for others. The Joint Legislative Audit Committee directed us to compare certain outcomes for dually involved youth, as described in the Scope and Methodology. Based on our review, we noted that on average the dual status counties had shorter lengths of juvenile justice involvement, fewer arrests, and a lower recidivism rate than nondual status counties. However, both dual and nondual status counties had similar average numbers of out of home placements after a youth’s joint assessment hearing. Furthermore, all six of the counties we visited provided a variety of services to dually involved youth, including mental health, substance abuse, youth development, and education services. Our review revealed that these youth typically received a significantly higher number of services after they became wards of the court in both dual status and nondual status counties. However, we also found that youth in dual status counties received more continuity of services from social workers than youth in nondual status counties because nondual status counties must close the youth’s dependency case when they become wards of the court, whereas dual status counties may keep those dependency cases open.

Dual Status Youth Appeared to Have Less Involvement with the Juvenile Justice System Than Crossover Youth

Our review of 166 case files indicated that youth in the dual status counties we visited had more successful outcomes on average related to juvenile justice than youth in nondual status counties. Best practice models define successful outcomes for juvenile justice as including a reduction in the length of juvenile justice involvement and a decline in delinquent behavior. Specifically, the Sierra Health Foundation’s Positive Youth Justice Initiative states that repeat delinquent behavior has negative long term effects for dually involved youth. We measured juvenile justice involvement from the date youth were declared wards of the court to the date their probation ended. We also reviewed the number of arrests and the recidivism rate for our selection in the six counties. Using these three outcomes, dual status counties appeared to perform better in the area of juvenile justice involvement.

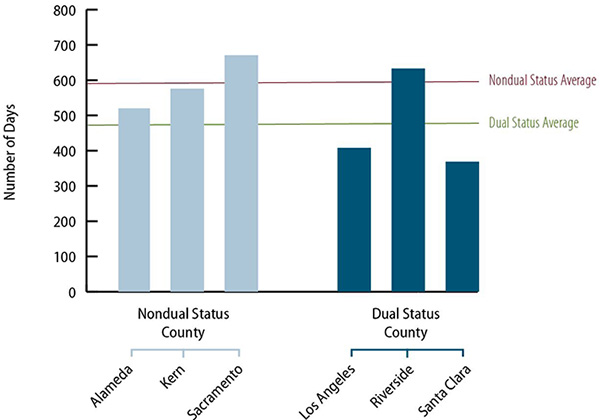

As shown in Figure 2, youth at the dual status counties we visited spent fewer days in the juvenile justice system than youth at nondual status counties. On average, dual status youth spent roughly 470 days in the juvenile justice system, whereas crossover youth in nondual status counties spent roughly 590 days in the juvenile justice system. With certain exceptions, until a youth turns 21, the court decides whether he or she remains in the juvenile justice system. Therefore, it is ultimately up to the discretion of the judges within each county to decide when to terminate a probation case.

Figure 2

Average Length of Juvenile Justice Involvement in Days

Sources: California State Auditor’s review of case files at Alameda, Kern, Los Angeles, Riverside, Sacramento, and Santa Clara counties for selected dually involved youth.

Note: Calculated as the number of days from the date that youth was adjudicated a ward of the court to the earlier of the date the court terminated the youth’s probation case or June 30, 2015.

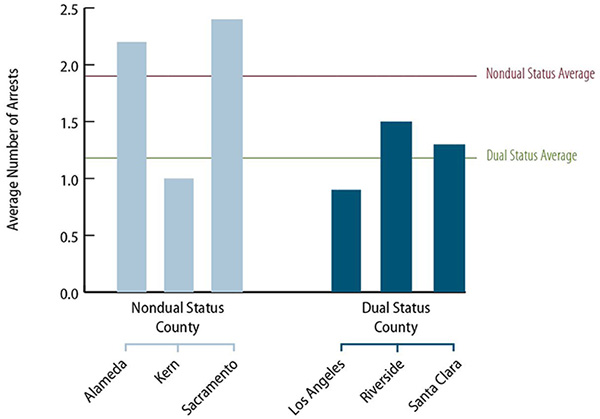

The shorter length of juvenile justice involvement we observed in dual status counties may be a reflection of the lower arrest rate of dual status youth we observed compared to crossover youth. Specifically, our review of 76 cases at dual status counties revealed that 46 youth, or 61 percent, were arrested at least once after becoming wards of the court. In contrast, of the 90 crossover cases we reviewed at nondual status counties, 62 youth, or 69 percent, were arrested at some point after becoming wards of the court. As indicated in Figure 3 below, the youth in dual status counties were arrested an average of 1.2 times, while youth in nondual status counties were arrested an average of 1.9 times. We found that Los Angeles County had the lowest average number of arrests, while Sacramento County had the highest average number. According to Sacramento probation’s division chief, youth who cross over from dependency into delinquency tend to commit multiple crimes and, in most cases, have multiple contacts with the county before crossing over. In addition, he explained that Sacramento follows a restorative justice philosophy of ensuring that the victim of a crime is made whole. As such, a youth on probation who has completed all court ordered services but has not fully paid court ordered restitution will remain on probation until restitution is paid, thus increasing the length of juvenile justice involvement.

Figure 3

Average Number of Arrests After Joint Assessment Hearing

Sources: California State Auditor’s review of case files at Alameda, Kern, Los Angeles, Riverside, Sacramento, and Santa Clara counties for selected dually involved youth.

Although the number of arrests may affect recidivism rates, we noted a narrower gap in recidivism related rates between dual status and nondual status counties. Of the six counties we visited, three had at least 50 percent of their youth recidivate. As described in the Introduction, after an officer cites or arrests a youth, the district attorney determines whether to file a petition, sending the case to court for a judge to review and determine whether to sustain the petition. We defined recidivism as including only youth who received sustained petitions while they were wards of the court through the end of probation.3 As shown in Table 4, one dual status county, Santa Clara, and two nondual status counties, Alameda and Sacramento, had at least a 50 percent recidivism rate for the cases we tested.

Los Angeles County had the lowest recidivism rate of the counties we tested. As Table 4 shows, only 30 percent of the youth we tested in Los Angeles County recidivated within our audit period. According to Los Angeles County probation’s director of the Northeast Juvenile Justice Center, drawing conclusions to a specific cause is very difficult; however, he believes that a combination of factors may contribute to the lower rate of recidivism. These factors include, but are not limited to, the following: the increase in diversion programs; the increase in community based services; the increase in aftercare services and targeted interventions based on risk and need. According to the placement unit supervisor at Kern County, the placement unit has put considerable effort into identifying youth’s specific needs, and it has trained the group homes it uses to address those specific needs. He stated that since the group homes provide youth with services specific to these needs, it reduces their risk of recidivating.

| County | Percent of Youth Who Recidivated | Average Number of Sustained Petitions Per Youth |

|---|---|---|

| Nondual Status | ||

| Alameda | 53% | 1.0 |

| Kern | 40% | 0.7 |

| Sacramento | 50% | 0.8 |

| Dual Status | ||

| Los Angeles | 30% | 0.4 |

| Riverside | 47% | 0.9 |

| Santa Clara | 50% | 1.1 |

| Total for Nondual Status | ||

| Total for Dual Status | ||

Sources: California State Auditor’s review of case files at Alameda, Kern, Los Angeles, Riverside, Sacramento, and Santa Clara counties for selected dually involved youth.

The Rates and Types of Out of Home Placement for Dually Involved Youth Appear to Be Similar in Dual and Nondual Status Counties

Youth in both dual and nondual status counties had a similar average annual number of out of home placements after their joint assessment hearings. Out of home placements include living arrangements such as foster homes, group homes, or relatives’ homes. Specifically, we found that youth were placed an average of 1.9 times per year after their joint assessment hearings in nondual status counties and 2.1 times per year in dual status counties. As mentioned in the Introduction, both CWS and probation agencies have a responsibility to provide youth with safe placements when they cannot safely live at home. In nondual status counties, once youth cross over to probation’s jurisdiction, probation officers identify the placements for the youth while they serve their time on probation. Probation officers have the option of placing youth in foster homes, relatives’ homes, group homes, or more restrictive in custody placements such as ranches, camps, or Department of Juvenile Justice facilities. For all six of the counties we visited, youth were most often placed in group homes for at least part of their probation. Of the youth we reviewed in nondual status counties, 81 percent were placed in group homes at some point after their joint assessment hearings, compared to 57 percent of the youth we reviewed in dual status counties. In nondual status counties, no other placement type exceeded 12 percent, while in dual status counties the next most common placement types that youth experienced were in custody placements, such as ranches and camps, at 25 percent, and foster homes, at 20 percent.

The Number and Continuity of Services Appear to Be Similar in Dual Status and Nondual Status Counties

Services Counties Offer to Dually Involved Youth May Include:

Mental Health Services

- Counseling, psychological testing, therapy

Substance Abuse Services

- Counseling, drug testing, support groups

Youth Development Intervention Services

- Anger management, gang prevention, independent living

Education Services

- Attendance monitoring, individualized education plans

Sources: Minute orders, court reports, and case plans in the counties of Alameda, Kern, Los Angeles, Riverside, Sacramento, and Santa Clara.

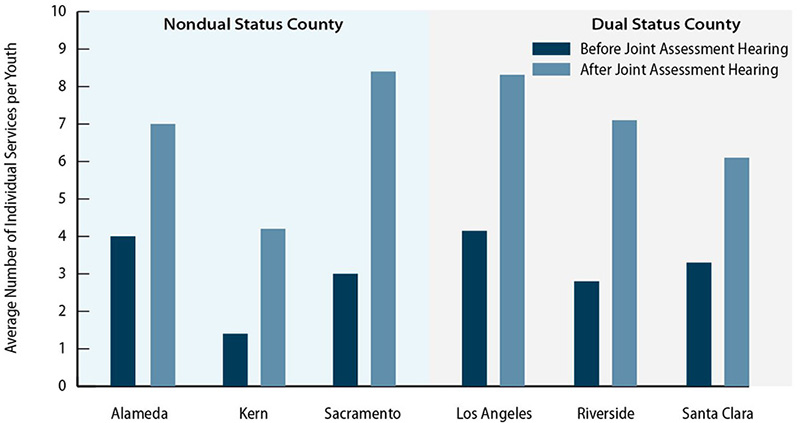

Youth typically received more services after they became wards of the court in both the dual status and nondual status counties we reviewed. As the text box illustrates, counties provided a variety of services to dependents and wards. State regulations require that before youth cross over, their social workers determine what services they need, include these services in case plans, and record what services the youth actually receive in case plan updates. After the court adjudicates dependent youth as wards of the court, probation officers reassess the services these youth need. Probation officers must create case plans that include the services to be provided. We reviewed case plans, case notes, status review reports, and other court reports to determine the number of mental health, substance abuse, youth development intervention, or educational services (services) counties provided before and after adjudication.

As shown in Figure 4, the average number of services that counties provided to youth increased after joint assessment hearings in both dual status and nondual status counties. For example, Sacramento County youth received on average 3.0 services before their joint assessment hearings and 8.4 services afterward. According to Sacramento’s assistant chief probation officer, when a youth crosses over from dependency to delinquency, the focus of the system shifts. Specifically, the reason youth are involved in dependency relates to the actions of their parents, but when these same youth cross over to delinquency, it is because of actions of the youth themselves. Therefore, the system shifts its focus to the youth’s behavior and how to best work with them. Dual status youth at Riverside County also had a significant increase in services, from 2.8 services on average before their joint assessment hearings to 7.1 services afterward. According to Riverside County’s supervising probation officer, youth who solely have a dependency or delinquency matter would receive a finite number of services from a singular agency. When they have an emergent issue that requires the attention of a second agency—usually leading to a dual status designation—the case merits increased services. Finally, similar to youth in other counties, youth in Kern County—despite having the lowest average number of services—saw the highest percent increase in services after their joint assessment hearings.

Figure 4

Average Number of Individual Services per Youth Before and After Joint Assessment Hearing

Sources: California State Auditor’s review of case files at Alameda, Kern, Los Angeles, Riverside, Sacramento, and Santa Clara counties for selected dually involved youth.

Furthermore, youth tended to receive additional types of services after their joint assessment hearings, regardless of whether they lived in a dual status or nondual status county. Table 5 below shows the number of dually involved youth in each county who received at least one service in one of four categories. At Riverside County, for example, 23 youth received mental health services before their joint assessment while 30 youth received mental health services afterward, an increase of 30 percent. We saw the biggest increases in substance abuse services and youth development intervention services. At Kern County, for example, only two youth received substance abuse services before their joint assessment hearing, but 26 youth received substance abuse services after crossing over to probation, an increase of 1,200 percent. Similarly, in Sacramento County, three youth received youth development intervention services before their joint assessment, but 24 youth received youth development intervention services after crossing over to probation, an increase of 700 percent.

| Mental Health Services | Substance Abuse Services | Youth Development Intervention Services | Education Services | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | ||||||||

| County and Number of Cases Tested | Joint Assessment Hearing | Percentage Difference | Joint Assessment Hearing | Percentage Difference | Joint Assessment Hearing | Percentage Difference | Joint Assessment Hearing | Percentage Difference | |||||||

| Nondual Status | |||||||||||||||

| Alameda—30 | 23 | 25 | 9% | 9 | 20 | 122% | 13 | 21 | 62% | 18 | 21 | 17% | |||

| Kern—30 | 14 | 26 | 86% | 2 | 26 | 1,200% | 12 | 24 | 100% | 3 | 8 | 167% | |||

| Sacramento—30 | 24 | 25 | 4% | 7 | 19 | 171% | 3 | 24 | 700% | 20 | 28 | 40% | |||

| Dual Status | |||||||||||||||

| Los Angeles—30 | 26 | 27 | 4% | 13 | 23 | 77% | 16 | 28 | 75% | 25 | 29 | 16% | |||

| Riverside—30 | 23 | 30 | 30% | 12 | 26 | 117% | 11 | 27 | 145% | 9 | 16 | 78% | |||

| Santa Clara—16 | 15 | 14 | (7)% | 6 | 14 | 133% | 7 | 13 | 86% | 9 | 9 | 0% | |||

Sources: California State Auditor’s review of case files at Alameda, Kern, Los Angeles, Riverside, Sacramento, and Santa Clara counties for selected dually involved youth.

In addition to more youth receiving more types of services, youth also generally received a greater number of each type of service after their joint assessment. For example, a youth in Riverside County received outpatient substance abuse services before her joint assessment hearing. After her joint assessment hearing, she continued to receive outpatient substance abuse services but also received additional substance abuse services, including drug testing, substance abuse counseling, and substance abuse education. We also noted instances in which counties did not continue providing youth with the services they received before crossing over. We found that, taken together, the six counties discontinued on average 16 percent of the services they had provided to youth before the joint assessment hearings. However, the counties appear to have mitigated these discontinuances with the significant increase in the number and types of services already discussed. For example, one youth in Alameda County received substance abuse education and substance abuse counseling before crossing over, but the county stopped providing him with these services after his joint assessment hearing. Although the youth lost these two services, he gained several new services, such as behavioral therapy, drug testing, and job training. The counties taken together increased the number of services they provided by 132 percent, on average.

Although youth generally received a significant increase in services, we found there was little continuity of involvement by court appointed special advocate (CASA) volunteers in both dual and nondual status counties mostly because tested youth generally did not have a CASA before becoming involved with probation. As shown in Table 6, continuity of CASA involvement did not exceed 3 percent in any of the counties. Judges appoint CASAs to watch over and advocate for abused and neglected youth, and CASAs typically stay with each case until it is closed and the youth is placed in a safe, permanent home. Our review revealed that only 15 of the 166 youth we tested had a CASA before their joint assessment hearing. A Santa Clara social services program manager explained that, although the CASA program encourages engagement with all dependent youth, younger children tend to receive CASA involvement more often than older youth. Youth whose cases we reviewed were generally in their late teens. Further, the assistant director of Alameda’s CWS agency explained that Alameda County has low availability of CASAs—only about 186 CASA volunteers serve approximately 1,600 dependent youth. She explained that it is hard to get these volunteers because of the time commitment the job requires. Additionally, according to a probation division director at Alameda, CASAs are only used by Alameda’s CWS agency. She explained that delinquency judges are able to appoint CASAs, but typically do not.

| County | Percentage of Cases With Continuity of Social Worker | Percentage of Cases With Continuity of Attorney | Percentage of Cases With Continuity of Advocate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nondual Status | |||

| Alameda | NA* | 7% | 3% |

| Kern | NA* | 40 | 0 |

| Sacramento | NA* | 0 | 3 |

| Dual Status | |||

| Los Angeles | 53% | 83 | 0 |

| Riverside | 30 | 30 | 0 |

| Santa Clara | 13 | 0 | 0 |

Sources: California State Auditor’s review of case files at Alameda, Kern, Los Angeles, Riverside, Sacramento, and Santa Clara counties for selected dually involved youth.

* Nondual status counties we visited close dependency cases when youth are adjudicated wards. Consequently, social workers are not assigned to the youth during their probation, and continuity is not possible.

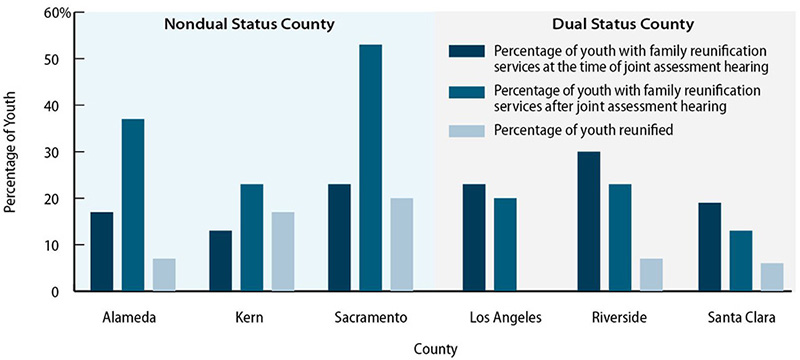

A County’s Model for Dually Involved Youth Appeared to Affect Family Reunification Services and Continuity of Some Staff

Our review of 166 case files indicated that family reunification services increased after youth became wards of the court in nondual status counties. Across all six counties, most of the youth whose cases we reviewed did not have ongoing orders for family reunification at the time of their joint assessment hearing; however, our review indicated that the probation agencies in nondual status counties tended to increase family reunification services when youth crossed over, while their counterparts in dual status counties tended to decrease these efforts. A potential cause for this difference is that in dual status counties, CWS remains involved and the county may not seek to reopen family reunification services if the dependency court has terminated family reunification services in the past. In contrast, nondual status counties close the CWS case, and in some situations probation may seek family reunification services despite the dependency court’s earlier decision to terminate family reunification efforts. For example, in one case we reviewed in Kern County, the CWS agency discontinued a dependent youth’s family reunification services in March 2011. In August 2012, at the youth’s joint assessment hearing, the court terminated the youth’s dependency case and declared her a ward of the court. Probation then reopened family reunification services for the youth and her family. Probation assessed this to be appropriate because the youth’s mother was participating in counseling and parenting classes. Probation reunified the youth with her mother in March 2013.

As shown in Figure 5 below, Sacramento County provided family reunification services to approximately 53 percent of the youth in our selection after their joint assessment hearings. According to the probation division chief for Sacramento County, if families are willing to work with the department and participate in family reunification services, reunification will be the target outcome. He said that once parents have shown a desire to participate, probation makes every attempt to achieve reunification and that only in cases where dependency has terminated parental rights will Sacramento probation not actively pursue reunification. He further stated that frequently cases come to probation from CWS with a case plan goal other than family reunification, but that probation likes to evaluate each case on its own merits and look at the case with fresh eyes.

In contrast, Figure 5 also shows that the percentage of youth in dual status counties who received family reunification services decreased after joint assessment hearings. In dual status counties, CWS agencies may act as the lead agencies for cases that originated in dependency. Because state regulations require social workers to consider family reunification services as a first option when determining case plan goals, CWS staff may have already pursued and terminated reunification services by the time youth are declared dual status. According to a probation division director at Riverside County, when youth are declared dual status and put into a delinquency placement, probation officers initially work to address the treatment needs of the youth rather than trying to reunify the youth with his or her parents. If the parents have custody rights, probation officers consider family reunification later, after the youth has been receiving services. Despite the varying rates of family reunification services, both dual status and nondual status counties had a low percentage of youth who were actually reunified; only about 10 percent of the 166 cases we reviewed resulted in successful reunification.

Figure 5

Percentage of Youth With Family Reunification Services and Outcomes

Sources: California State Auditor’s review of case files at Alameda, Kern, Los Angeles, Riverside, Sacramento, and Santa Clara counties for selected dually involved youth.

In addition, our review revealed that the lead agency dual status model appears to have stronger continuity of social workers than the on hold dual status model and the nondual status model. As we show earlier in Table 6, only youth in dual status counties were able to retain their social workers after their joint assessment hearings because their dependency cases usually remained active in those counties. Los Angeles and Riverside, both lead agency dual status model counties, had higher rates of continuity after the joint assessment hearings than Santa Clara, which used the on hold dual status model for most of the audit period. Of the 16 dual status youth we reviewed in Santa Clara, 13 were on hold dual status, while the remaining three were lead agency dual status. Santa Clara—originally an on hold dual status county—began declaring youth as lead agency dual status in August 2014, toward the end of our audit period. Santa Clara only had continuity of social workers for its lead agency dual status youth. This is consistent with what we expected from the on hold dual status model because the dependency case is suspended, similar to what occurs in the nondual status counties. Specifically, in nondual status counties, social workers do not continue serving youth after their joint assessment hearings because their dependency cases close at that time.

Further, our review revealed that a county’s use of the lead agency dual status model may affect a youth’s continuity of attorney more significantly than a county’s on hold dual status or nondual status model. As we show earlier in Table 6, youth in the counties of Kern, Los Angeles, and Riverside had stronger continuity of attorneys than the other counties. The youth whose cases we reviewed in Los Angeles County had an 83 percent rate of attorney continuity before, during, and after their joint assessment hearings. Contrary to what we expected for a nondual status county, Kern had a 40 percent continuity of attorneys. A division director at Kern’s probation agency explained that Kern County’s public defender’s office and indigent defense programs both assign attorneys to the juvenile court, which hears both delinquency and dependency cases. If a dependent youth crosses over to delinquency, the attorney assignment will not change as long as there are no conflicts.

Recommendations

To ensure that county CWS and probation agencies are able to identify their populations of dually involved youth, the Legislature should require Social Services to do the following:

- Implement a function within the statewide case management system that will enable county CWS and probation agencies to identify dually involved youth.

- Issue guidance to the counties on how to use the statewide case management system to track joint assessment hearing information completely and consistently for these youth.

To better understand and serve the dually involved youth population, the Legislature should require the Judicial Council to work with county CWS and probation agencies and state representatives to establish a committee, or to work with an existing committee, to do the following:

- Develop a common identifier counties can use to reconcile data across CWS and probation data systems statewide.

- Develop standardized definitions for terms related to the populations of youth involved in both the CWS and probation systems, such as dually involved, crossover, and dual status youth

- Identify and define outcomes for counties to track for dually involved youth, such as outcomes related to recidivism and education.

- Establish baselines and goals for those outcomes.

- Share the common identifier, definitions, and outcomes with the Legislature, for their consideration to require counties to utilize and track these elements.

If the State enacts data related requirements, it should require the Judicial Council’s committee to compile and publish county data two years after the start of county data collection requirements.

Alameda County and Sacramento County probation departments should update their existing procedures to ensure that their staff are accurately recording family reunification service components within the statewide case management system.

To identify their population of dually involved youth, CWS and probation agencies within each county should do the following:

- Designate the data system they will use for tracking the dates and results of joint assessment hearings.

- Provide guidance or training to staff on recording joint assessment hearing information consistently within the designated system.

We conducted this audit under the authority vested in the California State Auditor by section 8543 et seq. of the California Government Code and according to generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives specified in the Scope and Methodology section of the report. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Respectfully submitted,

ELAINE M. HOWLE, CPA

State Auditor

Date: February 25, 2016

Staff:

Jim Sandberg Larsen, CPA, CPFO, Audit Principal

Sharon Best

Andrew J. Lee

Brianna J. Carlson

Nate Jones, CFE

Aren Knighton, MPA

Erin Satterwhite, MBA

Caroline Julia von Wurden

Legal Counsel:

Stephanie Ramirez-Ridgeway, Sr. Staff Counsel

For questions regarding the contents of this report, please contact Margarita Fernández, Chief of Public Affairs, at 916.445.0255.

Footnotes

2 We also noted that the counties we visited define crossover youth and dually involved youth differently. For example, Los Angeles County defines crossover youth as any youth who has experienced maltreatment and engaged in delinquency. Thus, this definition would encompass all youth who are in both the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, even if they are not declared wards of the court. In contrast, Riverside defines them as youth with open dependency cases who are declared wards of the court at joint assessment hearings. Go back to text

3 The Chief Probation Officers of California adopted a similar definition of recidivism in 2011. Specifically, they define recidivism as a subsequent criminal adjudication/conviction while on probation supervision. Go back to text