Audit Results

The State Bar of California Has Not Ensured That Its Financial Reports Clearly Communicate Its Financial Situation

State law requires the State Bar of California (State Bar) to produce various financial‑related reports. The purpose of these reports is to present information necessary for stakeholders to understand the State Bar’s operations and for the Legislature to set its annual fees. However, in recent years, the State Bar’s reports have lacked the transparency necessary for the reports’ users to fully understand the State Bar’s financial situation. For example, the primary purpose of the State Bar’s Client Security Fund is to reimburse members of the public who suffer financial losses because of dishonest attorneys. However, for the past several years the State Bar has slowed its processing of many of these individuals’ claims because the Client Security Fund lacks the funds necessary to pay them. Rather than report this shortfall to stakeholders, in 2012 the State Bar decided to eliminate from its financial statements any disclosure of future amounts it estimated it would pay related to Client Security Fund claims that it had not yet approved. After we raised this issue with the State Bar, it added a disclosure in the notes to its 2015 financial statements noting this fund’s estimated payouts of $18.9 million.

We also identified a number of other instances in which the State Bar’s reporting lacked transparency. For example, because the State Bar failed to establish a reasonable process for allocating the costs of information technology (IT) projects, it identified the net position—the balance of assets less liabilities (balance)—in its Technology Improvement Fund as unrestricted, or available for general use, when in fact it was statutorily restricted to specific purposes. Further, the State Bar’s frequent changes in its presentation of indirect costs decreased its financial statements’ comparability and transparency. The State Bar also inaccurately identified its Legal Services Trust Fund as unrestricted when state law restricts the fund to awarding grants to entities that provide free legal services to low‑income Californians.

The State Bar Has Not Clearly Informed Stakeholders That It Lacks the Funding Necessary to Pay Victims of Attorney Misconduct

The Client Security Fund helps protect consumers of legal services by alleviating losses resulting from the dishonest conduct of attorneys. To protect the public, it reimburses money or property lost up to $100,000 related to any individual attorney. The fund’s primary source of revenue is an annual fee of $40 for active members and $10 for inactive members. Another source of revenue is recovery payments from the dishonest attorneys who have caused the State Bar to reimburse their clients. However, disbarred attorneys rarely pay the State Bar the money they owe, and the low level of recovery payments causes the State Bar to rely almost entirely on annual member fees to continue paying reimbursements from the Client Security Fund.

Since 2010, estimated future payouts to consumers have far outstripped the amount of money in the Client Security Fund available for payments. Because the State Bar did not take sufficient action when it first identified this potential problem, it is currently unable to make timely reimbursements to victims of dishonest attorneys. Further, in 2012 it changed its financial statements so that they no longer identify any of the State Bar’s estimated payouts related to such reimbursements. Consequently, stakeholders have lacked the information necessary to recognize that the Client Security Fund does not have the resources necessary to serve its primary purpose of protecting the public.

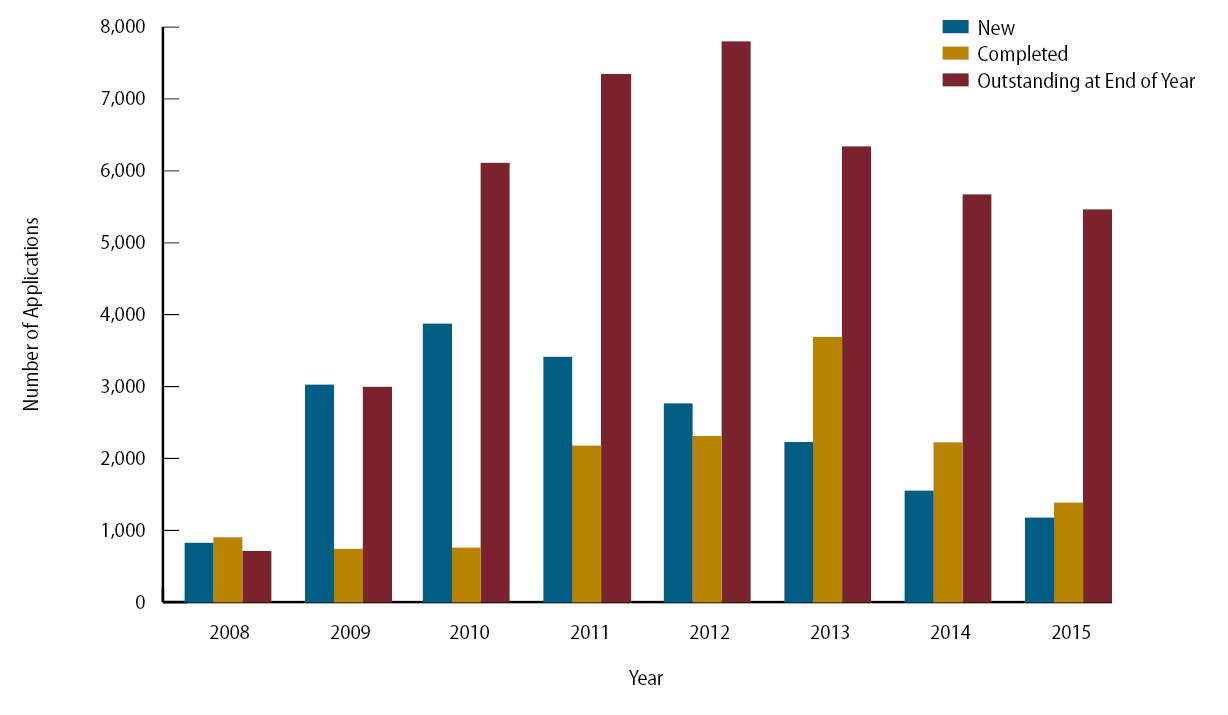

A 2015 report by the State Bar to its board of trustees (board) noted an unprecedented increase in claim applications for its Client Security Fund program beginning in 2009, with about half of the fund’s pending claims as of July 2015 related to loan modification schemes. In 2009 the number of new claim applications nearly tripled, as shown in Figure 3. The State Bar’s reports show that applications it received peaked at 3,900 in 2010, compared to only 800 applications in 2008. By the end of 2012, pending applications totaled 7,800. The Client Security Fund’s administrative costs rose as it employed temporary help and authorized overtime in 2013 and 2014 to help reduce the large inventory of pending applications, but at the end of 2015 the State Bar indicated it still had about 5,500 applications in process or awaiting payment, compared to only 710 applications at the end of 2008. The Client Security Fund currently has 11 staff, including three attorneys, who process the applications.

Figure 3

Number and Status of Applications to the State Bar of California’s Client Security Fund Program

Sources: Activities reports for State Bar of California’s Client Security Fund, 2008 through 2015.

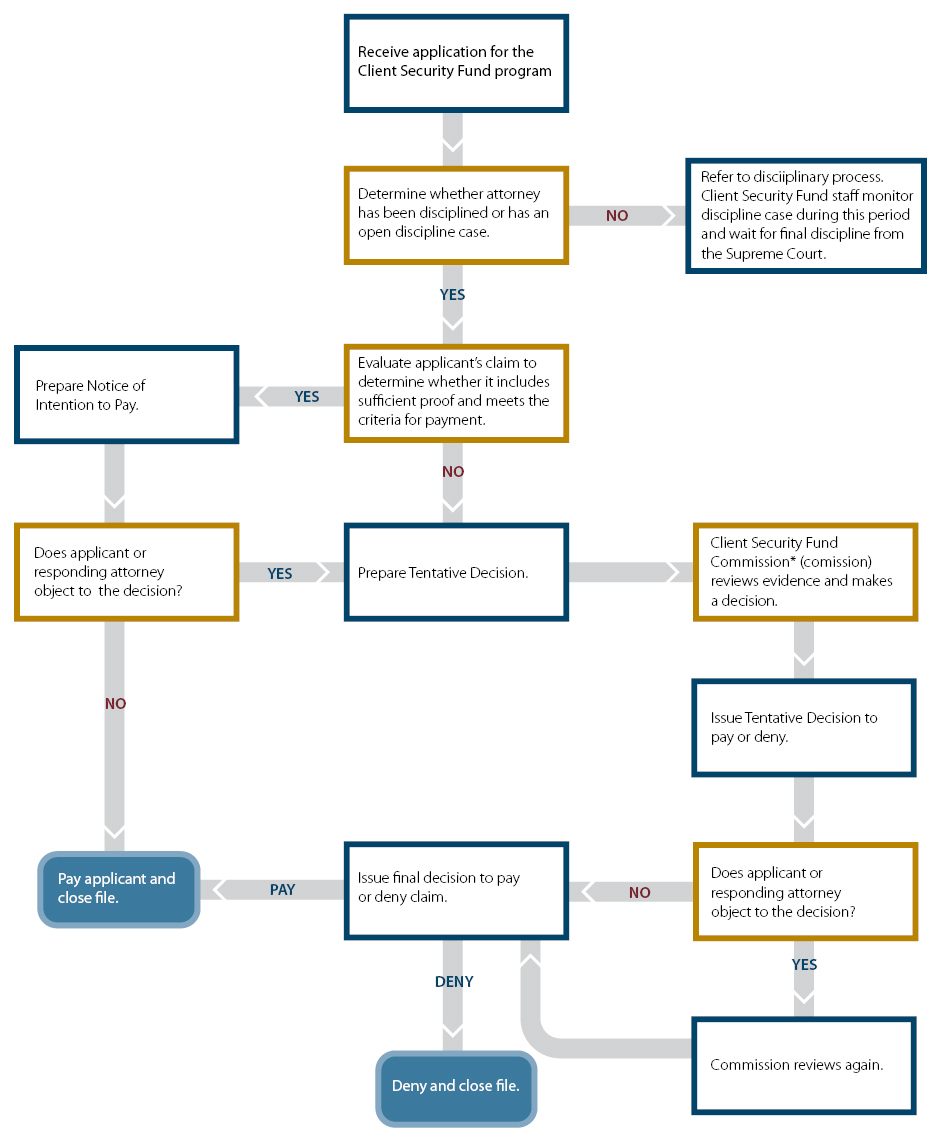

Client Security Fund applicants can experience significant delays in obtaining reimbursement for their claims in part because the State Bar has to wait to complete the processing of most applications until the California Supreme Court (Supreme Court) orders that the attorney in question be disciplined, as Figure 4 illustrates. The State Bar reported that in 2014 the median total time from its receipt of a complaint to the final decision by the Supreme Court was 505 days. Further, in March 2016, the State Bar reported that 1,100 claims filed during 2009 and 2010 against one attorney for loan modification schemes were still awaiting completion of the discipline process. Once the Supreme Court orders that an attorney be disciplined, the State Bar can pay the related claims from the fund if it has money available.

Nevertheless, even when the Supreme Court has disciplined attorneys involved in dishonest conduct, the State Bar has delayed processing applications because the Client Security Fund lacks the money necessary to make the payments. The State Bar’s report to its board in March 2016 stated that the current process to pay claims takes about 36 months after an attorney is disciplined because the Client Security Fund does not have the necessary funds. The State Bar has reported that historically it has paid applications 12 to 18 months after the discipline decision. Consequently, victims of dishonest attorneys can potentially wait four to five years from the time they submit their applications until the time they receive their payments. The State Bar’s long delays in paying claims harm the people who are waiting and who may be counting on these resources to meet basic needs. Moreover, the State Bar has commented to its board that long delays may cause it to lose track of applicants if they lose their homes or move without informing the State Bar of their new addresses.

Figure 4

The State Bar of California’s Review Process for Applications to Its Client Security Fund Program

Source: State Bar of California’s Client Security Fund Workflow and Client Security Fund Purpose and Process Summary.

* The commission is comprised of 7 volunteer members—four attorneys and three nonattorneys—appointed by the State Bar of California’s board of trustees

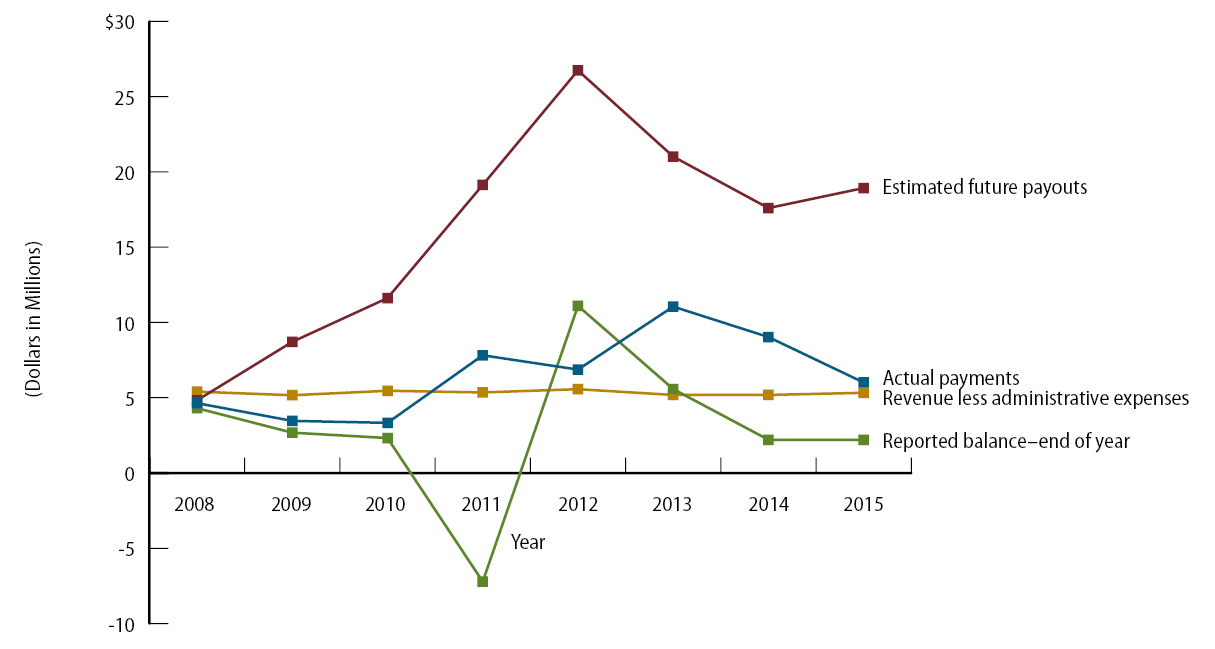

At the end of 2015, the amount of the State Bar’s estimated Client Security Fund payments far exceeded the amount of funds available, as shown in Figure 5. The State Bar estimates the amount it will pay in future years by using a ratio based on the amount the fund has historically paid for every dollar requested. At the end of 2015, the State Bar estimated that the payouts for its backlog of nearly 5,500 pending applications was $18.9 million; this backlog included about 270 approved applications awaiting payment of $1.3 million. Nonetheless, it had only $2.2 million available in its Client Security Fund at that time. In other words, the fund’s likely future payouts outstripped its assets by $16.7 million. To address its decreasing balance, between 2013 and 2015, the State Bar reduced the number of claims completed and the amount it paid in claims each year. In 2015 it paid only slightly more than it received in revenue, less administrative expenses.

Figure 5

Total Claims Paid by and Balances for the State Bar of California’s Client Security Fund From 2008 to 2015

Source: State Bar of California’s financial statements and Client Security Fund Ten‑Year Comparison schedule.

Further, between 2012 and 2014 the State Bar did not include information in its financial statements that inform stakeholders of its inability to pay claims. Specifically, in its 2012 financial statements, the State Bar disclosed that it had updated its legal analysis of rules governing the Client Security Fund and determined that it should not record a liability in its financial statements related to its estimated claim payments. The State Bar stated that until it had approved applications, it had not incurred a financial obligation related to them. Thus, by delaying its processing of the applications, it could effectively defer payments on those applications—and it could also defer informing users of its financial statements about the amounts that it expected to pay. This approach caused the $15.6 million deficit that the State Bar would have reported in 2012 to turn into a positive $11.1 million balance. Further, it allowed the State Bar to report that the fund’s net position—the difference between its assets and liabilities—remained constant at $2.2 million between 2014 and 2015, even though its estimated payouts actually rose to $18.9 million. Although the State Bar’s rationale for avoiding the reporting of its potential liability is defensible, we believe that it should have disclosed in the notes to its financial statements that it had a commitment related to a large, continuing estimated payout. After we discussed this issue with the State Bar it disclosed the fund’s estimated payout of 18.9 million in the notes to its 2015 financial statements.

In addition, the State Bar could have done more to communicate the Client Security Fund’s difficulties and offer proposed solutions sooner. In its 2013 budget submitted to its board, the State Bar stated that it might need to increase the fee it charged to members to maintain the Client Security Fund’s balance. However, it did not then include such an increase in its 2013 budget to the Legislature. Further, its 2016 budget submitted to the board and Legislature, did not discuss the strain on the Client Security Fund or propose any solutions. The State Bar’s lobbyist stated that the State Bar has discussed the shortage of money in the Client Security Fund with the Legislature for a number of years and has explored solutions with legislators, including a fee increase. She said that although a fee increase has been discussed, it has never made it into the State Bar’s fee bill. Despite discussions with individual legislators, we believe that it is important to present ongoing challenges and potential solutions in budget documents that are available to a wider audience of decision makers and stakeholders.

In March 2016, however, the board approved a transfer of $2 million to the Client Security Fund from the Lawyers Assistance Fund and the Legislative Activities Fund, making additional payouts possible.3 The State Bar’s chief operations officer (operations officer) said the State Bar is also considering requesting a three‑year fee augmentation to clear the Client Security Fund backlog and a permanent increase to support the program in the future. Further, she said that the board is also considering permanently redirecting half of the Lawyer Assistance Program fee to the Client Security Fund in order to reduce the level of proposed Client Security Fund fee increases. According to the State Bar’s estimates, such efforts would provide enough money to reduce the time to pay pending claims to eighteen months, once discipline is complete and the unit begins its evaluation of the related applications.

Methods of Pursuing Reimbursement for Client Security Fund Applications Payments

State Bar billing: The State Bar of California (State Bar) notifies disciplined attorneys when it makes payments from the Client Security Fund. Attorneys must reimburse the fund to continue practicing law, or in the case of disbarred attorneys, to return to the practice of law. Such payments accounted for about $818,000 of Client Security Fund recoveries during the past three years.

Collection agencies: For resigned and disbarred attorneys, the State Bar pursues debts through collection agencies. The State Bar stated that it has worked with three collection agencies in the last 10 years and that the latest agency chose not to renew its contract due to the difficulty in collecting these debts. Since 2013 the State Bar has collected $18,000 through this method.

Franchise Tax Board’s intercept program: For resigned and disbarred attorneys, the State Bar also sends the debtor accounts to a tax intercept program. This program reduces state tax refunds by the amount individuals owe government agencies. Since 2014 the State Bar has collected approximately $300,000. However, state law requires that the State Bar—rather than reimbursing the Client Security Fund— allocate money it receives through the tax intercept program to the Legal Services Trust Fund.

Money judgments: The State Bar files money judgments on court ordered debts it has deemed uncollectible by other means. However, because the court must have ordered the attorney to pay restitution to the Client Security Fund applicant, only certain cases meet the criteria for the State Bar to file money judgments. Since 2013 the State Bar has collected $74,000 through this method.

Source: Business and Professions Code, sections 6034 and 6140.5; the State Bar’s CSF Payment Summary Report and Discipline Payments Received Report; and the Franchise Tax Board’s website.

The need to augment the Client Security Fund fee is partly due to the fact that the State Bar has had little success in recovering costs from resigned or disbarred attorneys, who have little incentive to pay. State law allows the State Bar to recover costs from attorneys related to payments it makes from its Client Security Fund. The State Bar makes the vast majority of Client Security Fund payments because of misconduct by attorneys who later resign or are disbarred. At the end of 2015, the State Bar was owed approximately $91 million in outstanding debts associated with attorney misconduct, of which $74 million related to the Client Security Fund, on accounts open since 2003. However, between 2013 and 2015, the Client Security Fund reported recovering only about $910,000. Attorneys paid most of this amount through timely response to billings, but the State Bar recovered the rest through other efforts.

The State Bar uses four primary methods to pursue recoveries for Client Security Fund payouts, as shown in the text box. However, none of these methods has resulted in significant success. For example, collection agencies have generally been able to collect only small amounts from resigned or disbarred attorneys, and the State Bar has also received approximately $300,000 through the Franchise Tax Board’s intercept program over the past two years. However, state law requires that these funds go to the Legal Services Trust Fund to provide legal services to low‑income Californians rather than to the Client Security Fund.4

As the text box explains, the State Bar may pursue money judgments against attorneys who are delinquent on paying their debts. However, because the State Bar does not include all victims of an attorney’s misconduct as complaining witnesses for the discipline case against the attorney, the court does not order restitution for all victims. Only victims with restitution orders can receive money judgments. In cases without restitution orders, the statute of limitations to recover Client Security Fund payouts is three years rather than 10 years.

The State Bar is currently working through a backlog of outstanding debts that are eligible for money judgments. According to an assistant general counsel, the State Bar did not file money judgments between 2012 and 2013 because it had determined that the effort was not cost‑effective and because it had chosen to focus on the use of collection agencies. However, as of April 2016, the general counsel said it had filed approximately 375 money judgments totaling about $3.8 million. She stated that the State Bar is reviewing the remaining 1,200 debts, totaling approximately $7.6 million, and that it should file money judgments by September 2016 for all eligible cases completed before December 2015. Although the rate of payment on money judgments is low, the cost to process and file them is also low, so the State Bar says it will continue to seek money judgments.

The State Bar Has Not Accurately Reported Certain Restricted Funds Because It Lacks a Reasonable Process for Allocating Costs of Information Technology Projects

The State Bar has failed to establish a reasonable process for allocating the costs of IT projects; therefore, it has not ensured that it always identifies funds that are restricted to certain purposes by law. Specifically, in 2013 and 2014, it reported that the balance in its Technology Improvement Fund was unrestricted—or available for general purposes—when, in fact, most of the money making up the balance came from restricted sources and thus was limited to specific purposes.

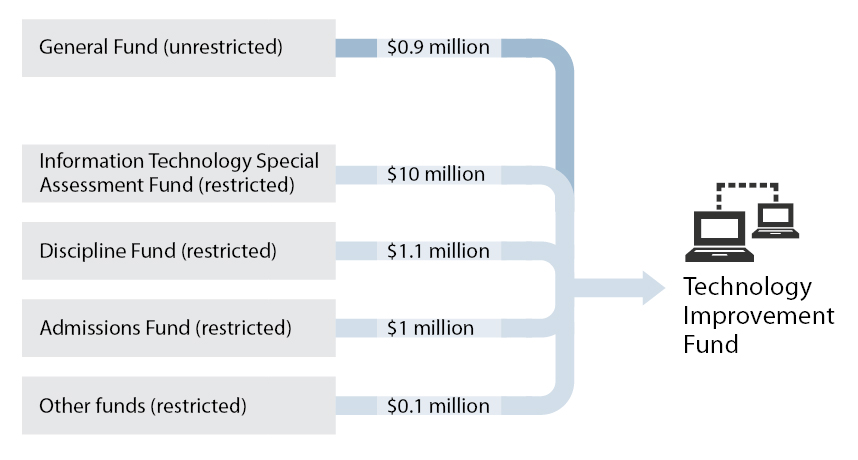

According to the State Bar’s financial reports, it established the Technology Improvement Fund to pay for IT projects that it had previously paid for through its general fund. Although it reported the ending balance in the Technology Improvement Fund as unrestricted in 2013 and 2014, only $944,000 of the $13.4 million that the State Bar transferred into the fund from 2008 through 2015 originated from unrestricted funds, as Figure 6 shows. The remaining money came from restricted sources, such as the IT Special Assessment Fund, the Admissions Fund, and the Discipline Fund. Consequently, in 2014 the State Bar overreported to stakeholders its level of funds available for general purposes by $4.6 million.

Figure 6

The State Bar of California’s Transfers To the Technology Improvement Fund From 2008 Through 2015

Source: State Bar of California’s Technology Improvement Fund reconciliation.

Note: Transfer amounts are rounded to the nearest hundred thousand. Actual amount transferred totaled $13.4 million.

According to the State Bar’s director of finance (finance director), the State Bar initially set up the Technology Improvement Fund to track IT project expenses, which would then be reimbursed by the State Bar’s other funds that benefit from the projects. However, the State Bar did not have a reasonable process for distributing IT project costs; and so lacked a solid basis to make transfers from other funds. In fact, the State Bar transferred more money into the fund than it needed to reimburse its costs, leaving a balance of $3.6 million in predominately restricted funds at the end of 2015. For example, according to the State Bar’s IT strategic plan for 2014 to 2018, the State Bar planned to use $1 million from its Admissions Fund to replace the admissions IT system. In 2012 the State Bar did transfer $1 million from this fund to the Technology Improvement Fund; nevertheless, the State Bar’s fund reconciliation indicates that it had only incurred about $173,000 in admissions project costs through 2015.

Because of the mix of restricted and unrestricted money in the Technology Improvement Fund, the State Bar cannot be certain which portion of the ending balance it should have reported as restricted. This problem will continue until the State Bar devises a reasonable method for allocating IT project costs that align project benefits with allocated amounts and matches the timing of expenses with incoming transfers.

In October 2015, the State Bar consolidated into its general fund the Technology Improvement Fund, along with seven other funds that account for building projects, indirect costs of the State Bar’s operations, retirement related resources, and unrestricted revenue. Our review found that this consolidation appears appropriate. Further, the State Bar accurately reported the fund’s remaining $3.6 million as restricted in its 2015 financial statements, despite the fund’s consolidation into the State Bar’s general fund.

The State Bar Has Frequently Changed How It Presents Certain Costs in Its Financial Statements, Causing the Statements to Lose Comparability

The State Bar of California’s Indirect Costs Include Costs Related to the following:

- General counsel

- Member billing

- Finance

- Human resources

- Information technology

- Administration and support

Source: State Bar of California’s indirect cost allocation methodology.

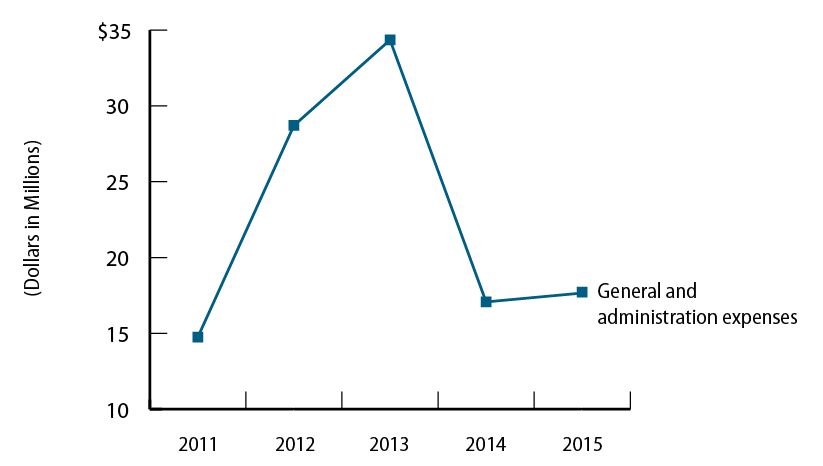

Multiple times over the past five years, the State Bar’s financial statements have lacked comparability of costs at the program level because the State Bar repeatedly changed the way it presented entity‑wide indirect costs that it allocated among its various funds. The text box lists the State Bar’s major sources of indirect costs. Because the State Bar has twice changed the way it reported these indirect costs since 2011, the general and administration expenses it reported have fluctuated significantly, as shown in Figure 7. Specifically, in 2012 and 2013, the State Bar allocated indirect costs at the fund level, thus grouping many of these costs into the general and administration expense line. In 2011, 2014, and 2015, the State Bar allocated indirect costs to a more detailed cost‑center level, allowing the State Bar to record these indirect costs in various other program expense lines rather than in the general and administration expense line.

As shown in Figure 7, these frequent changes reduce the comparability of expenses from year to year. In the Management’s Discussion and Analysis section of its 2012 financial statements, the State Bar highlighted the change in its presentation of indirect costs. However, the State Bar did not provide a similar explanation when it changed its presentation of indirect costs again in 2014, leaving stakeholders without the information necessary to understand the apparent cost fluctuations.

Expenses in the State Bar’s 2016 financial reports may lack comparability with expenses of previous years because the State Bar board has decided once again to change the way it allocates indirect costs. The State Bar will once more allocate indirect costs at a less‑detailed fund level, grouping many costs into the general and administration expense line. Although the State Bar’s revised methodology for allocating indirect costs is reasonable, we believe that the State Bar’s decision to make significant changes in accounting methodologies every few years reduces the usefulness and transparency of its financial reports. The State Bar could improve the comparability and understandability of these reports if it limited significant changes to its methodologies and if it highlighted any such changes when it chooses to implement them.

Figure 7

The State Bar of California’s General and Administration Expenses

2011 Through 2015

Source: State Bar of California’s annual audited financial statements from 2011 through 2015.

The State Bar Misclassified the Legal Services Trust Fund as Unrestricted and Did Not Report Its Administrative Expenses Accurately

The State Bar’s Legal Services Trust Fund Program makes grants to approximately 100 nonprofit organizations that provide free civil legal services to low‑income Californians. The program receives revenue from three different revenue sources: membership fees, donations, and interest on lawyer trust accounts recorded in the Legal Services Trust Fund; voluntary member donations recorded in the Justice Gap Fund; and filing fee revenue from the Judicial Council of California (Judicial Council) recorded in the Equal Access Fund.

Resources in the Legal Services Trust Fund are restricted to providing free legal services to low‑income Californians. However, the State Bar misclassified the balance in the Legal Services Trust Fund as unrestricted in its 2013 and 2014 financial statements, thus indicating that the State Bar could use these funds for other purposes. As a result, the State Bar misreported that it had $20.2 million available in unrestricted funds in 2014, when in fact $4.6 million of that amount represented the balance in the Legal Services Trust Fund and was restricted. According to the finance director, the State Bar classified this fund as unrestricted in those two years based on an analysis she performed in consultation with the State Bar’s Office of General Counsel and its external auditors. However, she could not explain the reasoning behind her analysis. The State Bar correctly classified this fund’s balance as restricted in its 2015 financial statements.

Further, because the State Bar incorrectly reported the costs of this fund, administrative costs for the Legal Services Trust Fund appeared to double in its 2014 financial statements when they actually changed only slightly. In 2013 and 2014, the Equal Access Fund experienced a $1.1 million shortfall in revenue due to a drop in filing fees. According to the managing director of the Legal Services Trust Fund, to minimize harm to grantees and to ensure the timely and full distribution of grants, the State Bar approved a $1.1 million interfund transfer from the Legal Services Trust Fund to the Equal Access Fund. This transfer was appropriate given that the two funds provide grants to the same recipients. However, the State Bar did not display this transaction as a transfer in its 2014 financial statements. Instead, it increased the Legal Services Trust Fund’s administrative costs by $1.1 million and decreased those of the Equal Access Fund by a similar amount. The former’s administrative costs thus appeared nearly to double from $1.3 million in 2013 to $2.4 million in 2014, while the latter’s administration costs went from a positive $604,000 in 2013 to negative $650,000 in 2014.

According to the Legal Services Trust Fund’s managing director, the State Bar correctly recorded the $1.1 million transaction in its general ledger system but inadvertently presented it in the audited financial statements under administrative expenses. We found that the State Bar lacked sufficiently detailed procedures to guide its staff in preparing financial statements and to guide its management in reviewing and approving them. The State Bar’s procedures did not include steps staff must take to ensure accounting data is accurately and completely presented in the financial statements. Further, these procedures did not describe management’s process for reviewing and approving the financial statements. Without such procedures, the State Bar risks making similar errors in its financial reports in the future.

The State Bar’s Compliance With a New Accounting Standard Caused It to Change the Way It Reports Pension Liabilities in Its Financial Statements

The State Bar recently implemented a new accounting standard that requires it to report a pension liability on the face of its financial statements. Specifically, in 2015 the State Bar implemented a new accounting standard, Government Accounting Standards Board 68 (GASB 68). As a result, for 2015 the State Bar reported a net pension liability of $31.2 million, representing the difference between its total pension liability and the assets it has set aside for the pension plan. Because of this change and the combined total of $9.2 million that the State Bar had misclassified as unrestricted balances in its Technology Improvement Fund and Legal Services Trust Fund (as previously discussed), the State Bar’s unrestricted balance appeared to fall precipitously from $20.2 million in 2014 to a deficit of $20.6 million in 2015.

However, the amount of the State Bar’s pension‑related liability did not change significantly; rather, the State Bar reported that amount differently. Specifically, GASB 68 requires governmental organizations to report on the face of their financial statements a net pension liability related to future benefit payouts as soon as their employees earn them. Under past accounting practices, such a liability was only disclosed in the notes to the financial statements. In the State Bar’s case, it reported a pension‑related liability of $27.3 million for 2013 in the notes to its 2014 financial statements.5 When it implemented GASB 68 in 2015, the State Bar reported an $18.8 million net pension liability for 2014 and a $31.2 million liability for 2015 on the face of its financial statements. Although GASB 68 changed the way organizations report pension liabilities, it did not require changes in the way organizations such as the State Bar fund their pension obligations. In fact, according to the State Bar’s financial statements, it has had enough assets set aside to fund 90 percent or more of its pension‑related liability in each year since 2012. Compared to the State of California, which had enough resources set aside to fund 74 percent of its pension liability in 2014, the State Bar’s pension plan is relatively well funded. Further, the State Bar paid 100 percent of its required annual pension contribution to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System from 2013 through 2015, a practice that it did not change as the result of implementing GASB 68. Thus, while the State Bar reported pension liabilities on the face of its financial statements in 2015 rather than in notes to the statements, this change did not significantly affect its financial situation.

Although the State Bar’s Reserves Are Generally Reasonable, It Has Not Adequately Communicated the Assumptions Underlying Its Budget

In our June 2015 report, we found that the State Bar had maintained excessively high balances in a number of its funds, and we recommended that it develop a plan to spend those balances. In response, the State Bar implemented a new fund reserve policy in February 2016. The general fund and Admissions Fund reserves appear to comply with this policy. However, we identified a number of concerns about the State Bar’s budgeting process. Specifically, the State Bar has not adequately documented its budget assumptions and methodologies. Further, it has not provided information on its budget assumptions and details regarding its funds to the Legislature. Finally, the State Bar recently entered into a loan agreement without informing the Legislature even though the agreement might have restricted the Legislature’s ability to lower the State Bar’s fees. After we informed the State Bar of our concerns, it modified this loan agreement to avoid such an outcome.

The Reserves for the State Bar’s Largest Funds Generally Comply With Its New Reserve Limits

As we noted in June 2015, the State Bar has historically reported excess funding from which it could draw to cover its costs. To address its excess balances, the State Bar implemented a new reserve policy in February 2016. In accordance with this policy, the State Bar calculates reserves as the excess of its current assets over its current liabilities. The resulting amount, referred to as working capital, is a measure of the ability to pay operating expenses in the short‑term. The new policy requires the State Bar to maintain reserves equal to 17 percent (or two months) of each fund’s annual operating expenses. This new policy also requires the State Bar to use reserves in excess of 30 percent of each fund’s operating expenses on a number of initiatives, which include offsetting member fees and supporting the Client Security Fund program where possible.

According to our analysis, which Table 6 shows, as of December 31, 2015, the State Bar’s general fund had $11.9 million in reserves, which met the 17 percent target. The Admissions Fund also met the target, with a $4.0 million or 20 percent reserve. In accordance with the new reserve policy, the State Bar is developing plans to spend certain funds’ excess reserves. For example, in March 2016, the State Bar informed its board that the California Board of Legal Specialization, which oversees the legal specialization programs, was in the process of developing a plan to reduce its reserve level, which was 301 percent over the 30 percent limit at December 31, 2015. The State Bar’s board also recently approved the transfer of $2 million from the Lawyers Assistance Fund and Legislative Activities Program Fund to its Client Security Fund to increase payments that alleviate losses resulting from the dishonest conduct of attorneys, as discussed earlier in the report. The State Bar’s plan to transfer these reserves and to spend an additional $147,000 from the Lawyer Assistance Fund on program evaluation and redesign would reduce from 86 percent to 33 percent of operating expenses the reserves listed in the column labeled Other Funds in Table 6.

| General Fund† | Admissions Fund | Client Security Fund* | Sections Fund | Legal Specialization Fund | Other Funds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current assets | $101,815,137 | $9,175,136 | $4,110,966 | $10,259,742 | $5,991,564 | $4,585,807 |

| Current liabilities | 89,885,322 | 5,159,600 | 1,895,629 | 1,648,031 | 573,759 | 1,087,861 |

| Working capital | 11,929,815 | 4,015,536 | 2,215,337 | 8,611,711 | 5,417,805 | 3,497,946 |

| Operating expense | 69,954,439 | 20,072,708 | 7,744,501 | 8,281,686 | 1,637,547 | 4,056,388 |

| Two months of operating expenses (17 percent) | 11,892,255 | 3,412,360 | 1,316,565 | 1,407,887 | 278,383 | 689,586 |

| Amount over or under two‑month reserve | $37,560 | $603,176 | $898,772 | $7,203,824 | $5,139,422 | $2,808,360 |

| Reserves percentage | 17% | 20% | 29% | 104% | 331% | 86% |

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of the State Bar of California’s financial statements for 2015.

Note: Grant‑related funds are excluded from this table. These funds’ reserves fluctuate routinely based on the cylical nature of their inflows and outflows.

* The Client Security Fund’s reserve does not reflect its need for additional resources. See the Audit Results section for further information regarding the Client Security Fund’s financial situation.

† General fund current assets exclude $3.6 million related to the Technology Improvement Fund. See the previous seciton for further information regarding the Technology Improvement fund.

The State Bar has not taken steps, however, to address the high reserve level in its Sections Fund. Its Sections Fund had $7.2 million more than it needed to meet the two‑month reserve target as of December 31, 2015, but the State Bar exempted the Sections Fund from having to spend its reserves once they exceed the 30 percent threshold. According to the operations officer, the State Bar Sections operate independently because attorneys voluntarily choose to be members of Sections and to pay the related annual fees. She said that because of this independence, the Sections may use reserves at their discretion as long as the Sections comply with legal requirements for the Sections Program to be self‑supporting. Nevertheless, given the high level of reserves, the State Bar should consider working with the Sections to reduce these balances.

The State Bar Did Not Adequately Document or Disclose Its Budget Process

The State Bar did not adequately document or communicate the assumptions and methodology it used when preparing its budget forecasts from 2013 through 2015. According to best practices established by the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) for financial forecasting in the budget preparation process, entities should clearly identify and make available to stakeholders their budget forecasts, along with those forecasts’ underlying assumptions and methodology.6 Although the State Bar included some of the necessary information in the budget documents it submitted to its board during the years in question, it did not provide the Legislature with any information regarding its budget assumptions and methodology. We find this particularly problematic because the Legislature uses the State Bar’s budget to determine appropriate member fee levels. The analyst involved in the budget process at the time could not explain why the State Bar did not include such information in the budgets it submitted to the Legislature. Consequently, the Legislature did not have important information necessary to question or evaluate the State Bar’s budget.

Further, when we asked the State Bar to provide complete documentation showing how it calculated its budget projections from 2013 to 2015, it was unable to do so. The State Bar’s budget process during this period involved each department director’s developing revenue and expenditure estimates for the upcoming year based on the previous year’s activity, with adjustments for anticipated changes. The directors submitted the budgets to a budget and performance analyst (analyst) in the Office of Finance, who compiled and consolidated them. According to the analyst, the former director of budgets, performance analysis, and internal audits (former budget director) developed revenue forecasts for future years based on revenue in the previous year and information provided by the directors. The analyst also stated that the State Bar’s budget database automatically calculated expense forecasts. However, other than spreadsheets of budget data and a few emails indicating that the senior director of admissions provided the analyst with estimates of revenue and expenses, the State Bar could not provide documentation regarding the assumptions or methodologies the former budget director used to develop the forecasts.

According to the finance director, the State Bar stopped using the budget database and transitioned to a more spreadsheet‑based process for the 2016 budget. She further explained that the old budget system did not allow users to see clearly the assumptions and methodologies underlying personnel cost estimates. However, at the time that the State Bar prepared its 2016 budget, it had not yet developed procedures to guide its staff and managers on preparing its budget using the new method. Without procedures and adequate documentation, State Bar staff are more likely to make errors when preparing the budget, and the State Bar is less able to provide critical information regarding its budget forecasts and assumptions to the Legislature or its other stakeholders.

The State Bar has also chosen not to follow advice that it adopt a more comprehensive and transparent budget process. Specifically, a consultant the State Bar hired to analyze its use of fund accounting recommended that the State Bar strongly consider preparing its budget document in accordance with California Society of Municipal Finance Officers (CSMFO) and GFOA excellence criteria. However, according to the State Bar’s operations officer, the State Bar’s existing budget and financial reporting practices already satisfy legal requirements and are in compliance with generally accepted accounting principles in terms of content, presentation, and design. In her view, the budget and financial statement models recommended by the CSMFO and GFOA are very comprehensive, and they would require extensive staff resources and additional qualified accountants to deliver. However, we believe the State Bar could benefit from following at least some portion of these best practices, such as presenting its underlying assumptions for revenue estimates and significant revenue trends.

Additionally, the State Bar made significant changes to the way it presented information about its funds in budget documents that it presented to the Legislature in February 2016. These changes significantly reduced the amount of information about its funds that the State Bar presented within the budget documents. Before 2016 the State Bar’s budget documents included fund condition statements, which identified each fund’s beginning balance, its revenue by type, and its expenses. In its 2016 budget documents, however, the State Bar instead presented a schedule showing fund reserves and containing information similar to that shown previously in Table 6.7 Although we agree that this schedule displays a useful measure of the State Bar’s reserves, its decision to eliminate fund condition statements removed detailed information about each fund’s major revenues and thus significantly decreased the transparency of the State Bar’s budgeting process.

State law requires the State Bar to present a budget in the same format as the budgets prepared by State departments for the governor’s budget. Further, state law requires the State Bar to provide supplementary schedules detailing its funds’ operating expenses and equipment, all revenue sources, any reimbursements or interfund transfers, and fund balances. However, the State Bar eliminated much of this information from its budget when it switched to providing a schedule of reserves. According to the finance director, the State Bar changed the presentation of its budget to the Legislature in order to increase transparency and to show the State Bar’s financial position at a consolidated level. Nonetheless, we believe that the required schedules also provide important information, such as detailed revenue sources. According to the operations officer, the State Bar’s new budget presentation complies with the requirements in state law because it provides revenue information at the fund level. However, she agreed that the presentation is not as thorough as it was in previous budgets, and said that the State Bar plans to provide a greater level of detail regarding revenue in future budgets.

Further, the State Bar did not provide the Legislature with information in its 2016 budget documents that would have allowed the Legislature to compare the budget under its new, consolidated fund structure to its previous year’s budget. As previously discussed, the State Bar consolidated eight of its funds into its general fund in 2015. Although the State Bar’s decision to consolidate funds for financial reporting is reasonable, it effectively eliminated comparability between its budgets for 2015 and 2016 because it did not provide the Legislature with information regarding its fund consolidation, such as a schedule showing the funds that it included in the consolidated general fund. Because the State Bar omitted information regarding its budget assumptions, fund conditions, and new fund structure, it prevented the Legislature from making fully informed decisions to authorize or modify fee levels.

After We Stated Our Concern the State Bar Modified Provisions in Its Building Loans that Might Have Otherwise Limited the Legislature’s Ability to Lower Member Fees

After we raised concerns about the structure of its loan agreements, the State Bar modified provisions in those agreements that might have limited the Legislature’s ability to lower membership fees for several years. In July 2015, the board asked the State Bar to conduct an analysis of the costs and benefits of improving its San Francisco building so that it could lease space on three vacant floors to tenants as well as to evaluate the feasibility of securing a loan to pay for the improvements. To evaluate the feasibility of a loan, State Bar staff held discussions with a number of financial institutions but received a proposal only from Bank of America. The State Bar has an existing loan agreement maturing in 2027 with Bank of America that it entered in 2012. The loan provided $25.5 million for the purchase of the State Bar’s Los Angeles building. In February 2016, the board approved the State Bar’s request to secure a $10 million bank loan to finance the San Francisco building’s improvements. The State Bar executed the agreement in March 2016, with a repayment period ending March 2026.

The initial terms of the State Bar’s new loan were substantially the same as the terms and conditions of its Los Angeles building loan, except that it secured the new loan in part by a pledge of revenue in lieu of the debt service reserve requirement included in the Los Angeles loan agreement. In addition, the bank agreed to substitute a pledge of revenue for the first loan’s reserve requirement. Therefore, the $4.6 million reserve that the State Bar previously established for the purpose of securing the Los Angeles building debt was slated to be returned to the State Bar’s general fund. The operations officer said that the loan terms provided financial benefits by freeing up reserve funds to address a number of the State Bar’s priorities, such as implementing recommendations related to workforce planning. However, the loans’ terms contractually required the State Bar to allocate its unrestricted future revenue first to the payment of both loans’ principal and interest.

By negotiating these loan terms, the State Bar obligated its future revenue in a way that might have limited the Legislature’s ability to lower fees. According to state law, whenever the board pledges revenue from membership fees, the “Legislature shall not reduce the maximum membership fee below the maximum in effect at the time such obligation is created or incurred, and the provisions of this section shall constitute a covenant to the holder or holders of any such obligation.” State law does not require the State Bar to notify the Legislature of this business decision or to seek its approval. After we asked the State Bar whether it had considered the potential effect of its action on the Legislature’s ability to lower fees, the State Bar amended both of its loan agreements to replace the revenue pledges with debt service reserves, thus again restricting the use of $4.6 million and restricting an additional $2.5 million until the loans are paid.

The State Bar Created an Unnecessary Nonprofit Organization, Then Used State Bar Funds to Cover the Nonprofit’s Financial Losses

With little or no board oversight, the State Bar created and used a nonprofit organization from 2013 through 2015. State law allows the State Bar to create nonprofit organizations for the purpose of generating additional revenue for its operations. According to the deputy general counsel, the State Bar has used nonprofit organizations in the past because they offer the incentive of tax deductibility for donations, an advantage the State Bar itself cannot offer. The State Bar’s former executive director incorporated the State Bar Access and Education Foundation (foundation) in May 2013 purportedly to collect money from donors and to administer activities benefiting the State Bar’s Legal Services Trust Fund and Sections Program. However, about two‑thirds of the expenses the State Bar recorded in the foundation’s fund from 2013 through 2015 were for purposes unrelated to these two programs. Further, the foundation’s expenses under the State Bar’s management significantly exceeded its revenue. In fact, in December 2015, the State Bar used almost $15,000 from nonmember fee revenue in its general fund to eliminate the foundation’s fund deficit. Without increased oversight, there is a risk that the State Bar could create similar nonprofits in the future and use their funds for questionable purposes.

The State Bar’s former executive director incorporated the foundation in May 2013 with bylaws that gave him and two other managers of the State Bar complete control and oversight. Specifically, the State Bar’s former executive director, former deputy executive director, and its former director of administration for member services were all directors of the foundation and had control over the receipt and use of all the revenue the foundation received, subject only to charitable trust restrictions.8 Further, the bylaws allowed these directors to authorize reasonable compensation for themselves for their services as directors. Although we found no instances in which the State Bar actually used the foundation to compensate its management, we find it deeply concerning that the State Bar was able to establish a nonprofit organization with provisions for such additional compensation.

According to our review of board documents between 2013 and 2015, the board was aware of the foundation but exerted little to no oversight of it. Specifically, the board included a description of the foundation’s fund in its policy manual but did not include in the manual any policies related to nonprofit organizations, including for their creation or oversight. Further, the State Bar’s deputy general counsel said that the board did not have any specific policy directing its oversight of any nonprofit that the State Bar establishes. The State Bar did not include the foundation’s fund in the budgets it submitted to its board, and it provided no detailed information regarding the foundation in the budgets it submitted to the Legislature.

We believe that this lack of policies for the oversight for nonprofit foundations contributed to the ability of the State Bar’s executive staff to create the foundation and to charge inappropriate expenses to it. Specifically, the State Bar charged to the foundation more than $22,000 in expenses that were unrelated to the Legal Services Trust Fund or Sections Program, the foundation’s ostensible beneficiaries. Of this amount, almost $4,800 was for a dinner event and hotel accommodations at the Citizen Hotel in Sacramento, as Table 7 shows. According to an email from the former chief financial officer to the finance director in January 2014, the former chief financial officer instructed that the cost of the dinner related to a State Fair project should be charged to the foundation. However, State Bar staff incurred the dinner and other Citizen Hotel expenses in February 2013, two months before the State Bar created the foundation and four months before the State Fair event. For the State Fair, the foundation further incurred around $17,300 in expenses related to an exhibit called A Conversation with Abraham Lincoln. The exhibit was a civic education and public outreach event developed by the State’s Third District Court of Appeal to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. These events and expenses were inconsistent with the foundation’s stated purpose of supporting both the Legal Services Trust Fund, which funds free legal services for low‑income Californians, and the Sections Program, which provides continuing legal education and other services for attorneys.

In September 2013, the former executive director and former deputy executive director created a resource sharing agreement between the State Bar and the foundation that said the State Bar might, at its sole discretion, cover foundation costs. Despite incurring about $22,000 in expenses between February and November 2013, the foundation only received $3,500 in corporate sponsor revenue and did not receive that until November and December 2013. As a result, in its 2013 financial statements, the State Bar reported a deficit of about $18,500 for the foundation’s fund.

| Invoice Date | Description | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| February 27, 2013 | Four rooms and banquet charges from the Citizen Hotel in Sacramento | $4,797 |

| June 21, 2013 | Emancipation Proclamation coloring book | 1,142 |

| July 13, 2013 | Painted artwork for booth at State Fair called Conversation with Abraham Lincoln | 1,200 |

| July 16, 2013 | Exhibit services for Freedom’s Promise exhibit at the State Fair | 11,048 |

| July 31, 2013 | Scholarship awards for State Fair essay contest | 3,875 |

| June 4, 2015 | Travel reimbursement for Tax Law Section | 128 |

| June 25, 2015 | Environmental Law Fellowship summer program stipend | 4,000 |

| July 16, 2015 | Environmental Law Fellowship summer program stipend | 4,000 |

| August 27, 2015 | Environmental Law Fellowship summer program stipend | 2,000 |

| Various | Bank charges | 1,149 |

| Total | $33,338 |

Source: State Bar of California’s bank documents, invoices, and accounting records.

In 2015 the State Bar’s Sections Program used the foundation for the purposes for which it was established. Specifically, the Sections Program used the foundation to pay about $10,000 for the 2015 Environmental Law Fellowship summer program. Nevertheless, because the State Bar already had a program in place to pay for such events and a process for receiving donations, we question the need for a separate nonprofit organization for this purpose.

Further, State Bar management violated the State Bar’s policy on transfers when it transferred in December 2015 without board approval about $14,800 of non‑member fee revenue from its general fund to the foundation’s fund to cover the foundation’s outstanding deficit. In our 2015 report, we recommended that the State Bar implement policies and procedures to limit its ability to transfer money between funds. In July 2015, the State Bar implemented a transfer policy that requires transfers between funds to be included in a budget or budget amendment that the board approves. The policy also requires the State Bar to support transfers by identifying a clear connection between the purpose of the transferring fund and the need for the transfer by the fund receiving the transfer. However, according to the finance director, State Bar senior management decided not to obtain board approval when transferring the $14,800 to the foundation because they believed the amount of money involved was insignificant and because the board had not been involved in the creation of the foundation. Instead, the former acting executive director approved the transfer, which the finance director recorded.

In addition, the State Bar did not involve the board in the dissolution of the foundation. In December 2015, the State Bar closed the foundation’s bank account, and in March 2016 it filed documents with the Secretary of State’s Office that formally dissolved the foundation. According to the finance director, State Bar senior management believed that because the board was not involved in the foundation’s creation, it was not required to approve its dissolution.

Before 2012 the State Bar had a similar nonprofit organization—the Education Foundation—that it used to fund some of its Sections’ educational programs. In its 2011 financial report, the State Bar reported a loss of about $746,800 for the Education Foundation’s fund. The State Bar also reported that it closed the Education Foundation as of December 31, 2011, and it used Sections resources to cover its loss. According to the State Bar’s deputy general counsel, the State Bar dissolved the Education Foundation because it believed additional administration was needed to ensure the Education Foundation operated substantially to serve the public interest and not just the legal community, individual lawyers, or its private sponsors. He further said the State Bar was concerned that the Education Foundation needed greater organizational formality, such as separate accounting records and bank accounts.

Despite these concerns over the use and administration of its previous nonprofit organization, executives at the State Bar created this most recent foundation in May 2013, less than a year and a half later, while providing no additional oversight to ensure the State Bar used it appropriately. Without appropriate oversight from its board and the Legislature, there is a risk that the State Bar could use its authority to create similar nonprofit organizations and use their funds for questionable purposes in the future.

The State Bar’s Management Violated Its Board Policies for Interfund Loans and Expenses

In addition to the inappropriate transfer described previously, the State Bar violated a board decision to pay interest on interfund loans. In April 2013, the board approved three loans totaling $4.3 million to its Los Angeles building fund from these sources: $3.5 million from the Legal Education and Development Fund, $782,000 from the Elimination of Bias and Bar Relations Fund, and $52,000 from the Legislative Activities Fund.9 The board approved these three loans for a term of up to 10 years with an annual interest rate of 4.26 percent, the same rate the State Bar paid for its Los Angeles building bank loan.

According to an email from the former acting general counsel, the State Bar expedited the repayment of the three loans, paying the full amount in less than two years to avoid paying interest over the remaining term. We found that the State Bar repaid the principal of these three loans in full by December 2014. However, the State Bar failed to pay the $258,000 due in interest at the time of its repayment. According to the finance director, the former acting chief financial officer believed that it did not make sense for the lending funds to earn 4.26 percent interest when these funds would have earned less than 1 percent interest on deposits in the investment pool. However, we find it problematic that the former acting chief financial officer did not follow the board‑adopted loan agreement.

Additionally, we found that the State Bar violated its expense policies in 2013. According to the finance director, the former chief financial officer instructed her to issue a $15,000 check for a board president’s stipend in July 2013. The State Bar could not provide documentation of a check request or two levels of approval for this transaction, as required by its policies. Further, we found that the State Bar issued the stipend check several months before the president was sworn in. During the course of our audit, the State Bar removed from its policies the provision for a president’s stipend. However, by failing to follow its policies, the State Bar bypassed controls meant to ensure its expenses were reasonable and necessary.

The State Bar’s Salaries for Its Executives Are Significantly Higher Than Salaries for Comparable Positions in State Government

The State Bar’s salaries are its largest and fastest‑growing expense. This situation has occurred in part because the State Bar’s pay scales for executive staff salaries are significantly higher than those of executive staff in state government agencies. In fact, as Table 8 shows, the maximum salaries for the State Bar’s 13 top executives exceed the annual salary paid to the governor. For example, the senior director of admissions’ maximum annual salary is $208,255, more than the governor’s annual salary of $182,784. This senior director’s responsibilities include overseeing, planning, organizing, and directing the examination and admission of attorneys to the State Bar. In contrast, the maximum salary for state agencies’ civil service executives with comparable responsibilities—known as career executive assignment positions (CEA positions)—is $135,948, while civil service CEA attorneys, earn no more than $172,908.10 Even though the State Bar recently eliminated several executive positions as noted in the Introduction, it estimated that its remaining 48 executive staff positions would cost $7.9 million during 2016. After adjusting for regional salary differences in Los Angeles and San Francisco, this amount is equivalent to roughly $7.3 million in salary costs for comparable positions in Sacramento, which has the highest concentration of state employees. If the State Bar capped all executive staff salaries in positions below that of the operations officer at the highest level for comparable CEA positions, it could save as much as $428,000 annually, after taking regional differences into account.

Additionally, the State Bar provides most of its executive staff with benefits that are more generous than the State gives to those in CEA positions. For example, State Bar executive staff receive health, dental, and vision benefits that cost the State Bar nearly $38,000 per person annually. This amount is almost double the amount that the State pays for its CEA positions’ benefits—about $19,500 annually. If the State Bar capped its employer contributions at the level that the State uses, it could save as much as $433,000 annually.

| Title | Agency | Salary |

|---|---|---|

| Executive Director/CEO | State Bar of California (State Bar) | $267,500 |

| Agency Secretary | California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation | 243,360 |

| Chief Operating Officer | State Bar | 239,500 |

| Director | California Department of Public Health | 239,064 |

| Chief Trial Counsel | State Bar | 229,079 |

| Director | California Department of Social Services | 219,264 |

| Chief Legal Officer | State Bar | 216,869 |

| Deputy General Counsel | State Bar | 208,255 |

| Senior Director, Admissions | State Bar | 208,255 |

| Senior Director, State Bar Court | State Bar | 202,257 |

| Senior Director, Information Technology | State Bar | 195,445 |

| Executive Director | State Board of Equalization | 188,448 |

| Deputy Chief Trial Counsel | State Bar | 188,223 |

| Chief Assistant General Counsel | State Bar | 188,223 |

| Senior Director, Education | State Bar | 187,927 |

| Senior Director, Administration of Justice | State Bar | 187,927 |

| Director, General Services | State Bar | 187,676 |

| Governor | State of California | 182,784 |

| Director | California Department of Water Resources | 177,683 |

| Director | California Department of Transportation | 177,683 |

| Top Allowable Career Executive Assignment (CEA) salary for positions requiring licensure as an attorney, engineer, or physician. | CEA | 172,908 |

| Assistant Chief Trial Counsel | State Bar | 171,983 |

| Assistant Chief Trial Counsel | State Bar | 171,983 |

| Chief Assistant Court Counsel | State Bar | 171,983 |

| Director, Client Security Fund | State Bar | 171,983 |

| Director, Professional Competence | State Bar | 171,983 |

| Director | California Department of General Services | 171,545 |

| Director | California Department of Human Resources | 171,168 |

| Chief Counsel | California High Speed Rail Authority | 168,216 |

| Assistant Chief Trial Counsel | State Bar | 166,650 |

| Director | Department of Consumer Affairs | 161,650 |

| Director | California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery | 161,650 |

| Director | Employment Development Department | 161,640 |

| Assistant Chief Trial Counsel | State Bar | 161,600 |

| Director, Finance/Controller | State Bar | 159,363 |

| Director | Department of Motor Vehicles | 156,936 |

| Court Administrator | State Bar | 154,125 |

| Director, HR and Labor Relations | State Bar | 154,125 |

| Court Administrator | State Bar | 154,125 |

| Director, Information Systems and Business Solutions | State Bar | 154,125 |

| Director of Applications | State Bar | 154,125 |

| Director, Central Administration, Chief Trial Counsel | State Bar | 152,712 |

| Chief Assistant Court Counsel | State Bar | 151,500 |

| Director, Operations and Management | State Bar | 151,281 |

| Director, Examinations | State Bar | 151,281 |

| Director, Legal Specialization | State Bar | 151,281 |

| Director, Technology Systems | State Bar | 149,841 |

| Director, Educational Standards | State Bar | 149,841 |

| Director of Administration | State Bar | 145,440 |

| Director, Moral Character Determinations | State Bar | 141,400 |

| Director, Procurement and Risk Management | State Bar | 140,788 |

| Deputy Director, Operations and Management | State Bar | 140,172 |

| Managing Director, Bar Relation | State Bar | 140,172 |

| Managing Director, Diversity Outreach | State Bar | 140,172 |

| Managing Director, Legal Services Trust Fund | State Bar | 140,172 |

| Director, Communications | State Bar | 138,127 |

| Top Allowable CEA Level C | CEA | 135,948 |

| Director, Section Education and Meeting Services | State Bar | 131,578 |

| Managing Director, Planning Admin | State Bar | 129,126 |

| Top Allowable CEA Level B | CEA | 128,436 |

| Director, Lawyers Assistance Program | State Bar | 126,250 |

| Director, Fee Arbitration | State Bar | 123,699 |

| Managing Director, Member Records, and Compliance | State Bar | 123,048 |

| Finance Manager | State Bar | 118,789 |

| Deputy Director, General Services | State Bar | 111,862 |

| Top Allowable CEA Level A | CEA | 111,324 |

Sources: The State Bar’s website and California Human Resources website.

Note: Green highlights indicate salaries of executive branch staff within state agencies.

Like the State Bar’s other executive staff, the executive director receives significantly more in terms of salary and benefits than she would at a state agency. The executive director negotiates his or her contract directly with the board. The State Bar pays its current executive director an annual salary of $267,500. The executive director is most similar to the director of an agency with fewer than 800 employees. However, the top directors for the Department of Social Services and the Board of Equalization—who each oversee 4,000 employees—are eligible to receive maximum salaries of $219,264 and $188,448, respectively. The State Bar’s executive director also receives $36,000 annually in lieu of receiving health, dental, and disability benefits. The payment in lieu of insurance is comparable to the amount the State Bar spends on insurance for a number of its other executives, as previously noted; however, this payment far exceeds the $1,860 per year that the State pays to employees who opt out of insurance. In 2015 and 2016 the State Bar also paid its executive director a total of $32,500 for a housing allowance and moving expenses, but this expense payment is not an ongoing benefit. Although state agencies can pay for relocation expenses, state policy imposes stringent requirements that are absent from the State Bar’s policies.

The State Bar has not conducted an in‑depth update of its job classification and compensation structure throughout the organization in more than 10 years, but it is currently in the process of performing a study that would enable such an update. Senate Bill 387 of 2015 requires the State Bar to conduct a public sector compensation and benefits study (compensation study) for staff involved in its disciplinary activities. However, the State Bar expanded this compensation study to include all of its positions, not just those related to attorney discipline. Its current structure includes approximately 150 job classifications that encompass approximately 600 positions. In February 2016, the State Bar hired CPS HR Consulting (CPS) to complete the compensation study of all of its departments. The agreement requires CPS to develop a new classification structure, assign all employees to classifications, conduct a survey of public sector salaries, and develop a new salary step plan. To assess the need for a new classification structure, the State Bar also sent position description questionnaires to staff in the Office of the Chief Trial Counsel (Trial Counsel). CPS must issue a final report on its analysis of the staff involved in the State Bar’s discipline activities of the Trial Counsel by May 15, 2016, and for the remaining State Bar departments by October 3, 2016.

Agencies to which the State Bar was Comparing Itself when Determining Executive Compensation

Counties: Alameda, San Francisco*, Los Angeles, Orange, Santa Clara

Cities: Anaheim, Long Beach, Los Angeles, Oakland, San Jose

Superior Courts: Alameda County, Los Angeles County, San Francisco County

Judicial Council of California

Los Angeles Unified School District

*San Francisco is both a city and a county.

Source: The State Bar of California’s selection of comparable agencies.

Although we believe a compensation study will prove helpful to the State Bar, we were concerned that it was not considering the State’s executive branch agencies when determining appropriate salary ranges. The State Bar had selected 15 agencies it deemed comparable to itself. They included five counties, five cities, three superior courts, the Los Angeles Unified School District, and the Judicial Council, as listed in the text box. After we brought this to the attention of the operations officer, the State Bar added a State executive branch salaries and benefits comparison to its compensation study covering staff involved in its disciplinary activities. The operations officer said the State Bar would also include comparisons to the State’s executive branch in its agency‑wide compensation study.

Recommendations

To reduce the length of time that victims of dishonest lawyers must wait for reimbursement from the Client Security Fund, the State Bar should continue to explore fund transfers, member fee increases, and operating efficiencies that would increase resources available for payouts. To ensure that it maximizes its cost‑recovery efforts related to the Client Security Fund, the State Bar should do the following:

- Adopt a policy to file for money judgments against disciplined attorneys for all eligible amounts as soon as possible after courts settle the discipline cases.

- Evaluate annually the effectiveness of the various collection methods it uses to recover funds from disciplined attorneys.

To reduce the risk of errors in financial reporting, the State Bar should update its procedures to include guidance on the following:

- Detailed steps that staff should take to prepare financial statements and to ensure that the statements are accurate and complete.

- Management’s review and approval of financial statements.

To increase the transparency and comparability of its financial information, the State Bar should do the following:

- Limit significant changes in its indirect cost reporting.

- Clearly disclose any changes in its accounting practices.

- Disclose the reasons for any significant changes to program costs. To ensure that it accounts appropriately for information technology project costs and their related funding sources, the State Bar should do the following:

- Develop a reasonable method for allocating information technology project costs.

- Apply this new cost‑allocation method to the costs of its Technology Improvement Fund.

To ensure it informs stakeholders of conditions that may affect its policy and programmatic decisions, the State Bar should document the assumptions and methodology underlying its budget estimates. It should concisely present such assumptions and methodology in the final budget document it provides to its board and the Legislature.

To make certain that its budget documents conform to the requirements in state law and that they are comparable to prior budgets, the State Bar should do the following:

- Establish a process for ensuring that budget documents conform to the requirements in state law.

- Update its budget policies to require supplementary schedules and narratives for any budget in the year in which the State Bar implements changes to the presentation of its budget.

To ensure that the State Bar’s board can make informed decisions about its consultant’s recommendations regarding budgeting and financial reporting, the State Bar should analyze the costs and benefits of implementing its consultant’s recommendations about budgets and present this analysis to its board for consideration.

To make certain that the Legislature is not limited in its ability to set member fees, the Legislature should require the State Bar to notify or seek its approval when the State Bar plans to pledge its member fee revenue for a period that exceeds 12 months or overlaps fiscal years.

To ensure that it retains appropriate supervision and control over the State Bar’s financial affairs, the board should establish a policy that includes the following:

- A description of the parameters for the creation of nonprofit organizations limiting such organizations to the purposes consistent with the law and the State Bar’s mission.

- A description of the board’s oversight role in relation to the State Bar’s nonprofit organizations.

- Requirements to make sure that the board reviews and approves all documents the State Bar uses in the creation and use of a nonprofit organization, including original and amended bylaws as well as agreements between the State Bar and the organization.

- Requirements ensuring that the board reviews, approves, and monitors regularly the budgets and other financial reports of any nonprofit organizations.

- Requirements that the State Bar develop policies and procedures to prevent the mingling of the its funds and any nonprofit organization’s funds.

To improve its oversight of the State Bar’s financial affairs, the Legislature should require the State Bar to disclose the creation of and use of nonprofit organizations, including the nonprofits’ annual budgets and reports on their financial condition explaining the sources and uses of the nonprofits’ funding.

To ensure that the compensation it provides its executives is reasonable, the State Bar should do the following:

- Include in the comprehensive salary and benefits study that it plans to complete by October 2016 data for the salaries and benefits for comparable positions in the state government’s executive branch.

- Revise its policy for housing allowances and relocation expenses to align with the requirements in the state law that are applicable to managerial employees.

We conducted this audit under the authority vested in the California State Auditor by Section 8543 et seq. of the California Government Code and according to generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives specified in the Scope and Methodology section of the report. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Respectfully submitted,

ELAINE M. HOWLE, CPA

State Auditor

Date:

May 12, 2016

Staff:

Jim Sandberg‑Larsen, CPA, CPFO, Audit Principal

Angela Dickison, CPA, CIA

Andrew J. Lee

Brigid Drury

Carol Hand

Aren Knighton, MPA

Caroline Julia von Wurden

IT Audits:

Lindsay M. Harris, MBA, CISA

Shauna M. Pellman, MPPA, CIA

Legal Counsel:

Stephanie Ramirez‑Ridgeway, Sr. Staff Counsel

For questions regarding the contents of this report, please contact

Margarita Fernández, Chief of Public Affairs, at 916.445.0255.

Footnotes

3 The Lawyer’s Assistance Fund receives mandatory member fees, and the Legislative Activities Fund receives voluntary member fees. Go back to text

4 In rejecting the State Bar’s request to participate in the tax intercept program in 2001, the Senate Judiciary Committee’s analysis concluded that ensuring that attorneys pay their debts in order to reduce annual bar dues does not rise to the same level of public service as collecting unpaid child support, for example. After 2014 the Legislature permitted the State Bar to use the tax intercept program under the condition that it give recovered money to the Legal Services Trust Fund. Go back to text

5 Reported pension information may be up to one year old depending primarily on the timing of actuarial valuations. Go back to text

6 The GFOA represents public finance officials throughout the United States and Canada. Its mission is to enhance the professional management of governmental financial resources by identifying, developing, and advancing financial strategies, policies, and practices. Go back to text

7 In its 2016 budget documents, the State Bar refers to its fund reserves as projected working capital. Go back to text

8 A revision to the foundation’s bylaws in October 2015 replaced the director of administration for member services with the State Bar’s assistant secretary as a director of the foundation. Go back to text

9 The State Bar refers to the three funds collectively as the Administration of Justice Fund. Go back to text

10 CEAs are high administrative and policy influencing positions within state civil service, and often have direct contact with department directors. They may often compose the executive management team and have primary responsibility for managing agencies’ major functions. Go back to text