Audit Results

The University of California, Davis Has Not Determined How It Will Address the Strawberry Breeding Program’s Recent Loss of Funding

Historically, the Strawberry Breeding Program (strawberry program) has generated millions of dollars in patent income for the University of California, Davis (UC Davis). As described in the Introduction, the strawberry program received an allocation of the patent income it earned and additional funding from its various research agreements. In fiscal year 2011–12, these research agreements provided $945,000 of funding to the strawberry program. However, as explained in the Introduction, these agreements ended during fiscal year 2012–13. As a result, the strawberry program’s funding from these agreements decreased by $172,000, or 18 percent, in fiscal year 2012–13. The discontinuation of these agreements also significantly contributed to the strawberry program’s loss of funding in fiscal year 2013–14, when it received only $910,000, a 56 percent decrease in funding from the prior year.2 Because the strawberry program’s fiscal year 2013–14 revenues were significantly less than its direct expenses of almost $1.6 million, it used roughly 37 percent of its $1.8 million in reserves to cover this funding shortage. Such a drop in funding places the viability of the strawberry program in jeopardy because the University of California’s (university) existing funding mechanisms for the strawberry program did not adequately cover this recent loss. Although UC Davis has publicly stated that it has an unwavering commitment to continue its strawberry program, it has not developed a balanced budget that addresses how it will fund this program in the future.

UC Davis Has Options for Increasing Revenue to the Strawberry Program

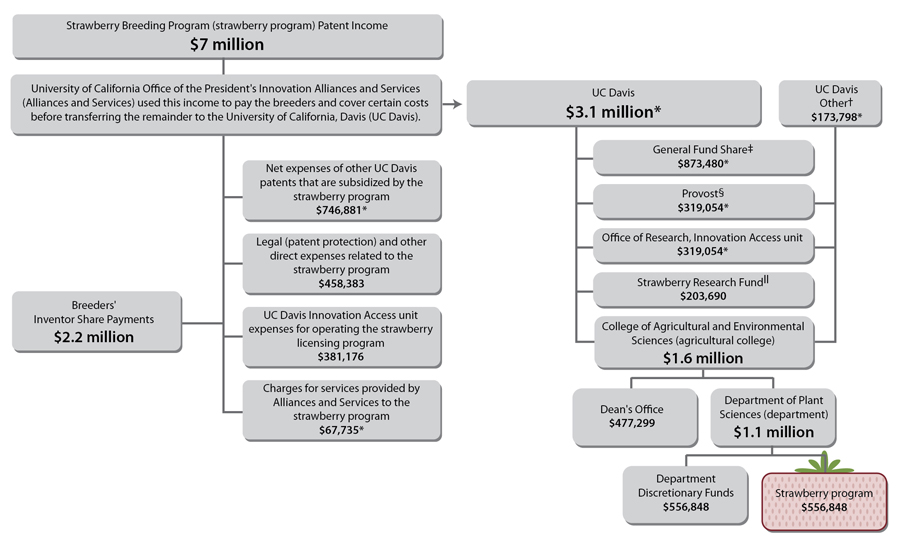

The university’s Office of the President’s Innovation Alliances and Services (Alliances and Services) collects patent income from all UC Davis patents and uses this aggregate sum to pay all patent-related expenses and to pay individual inventors for their share of the income, before distributing the remaining amount to UC Davis. As shown in Figure 3 below, the strawberry program generated roughly $7 million in patent income in fiscal year 2010–11. Alliances and Services used this income to pay the former breeders and various other expenses before distributing the remaining $3.1 million to UC Davis, which then ultimately distributed only $556,848 to the strawberry program.

Figure 3

Distribution of Strawberry Breeding Program Patent Income Earned in Fiscal Year 2010–11

Sources: Accounting records from UC Davis’ Kuali Financial System; the University of California, Los Angeles’ Financial System General Ledger Applications system; the University of California (university) Office of the President’s Patent Tracking System; UC Davis’ issue report titled UC Davis Budget Model: Allocating Patent Revenues: Transitions to Align With the Incentive-Based Budget Model; UC Davis’ Internal Audit Services’ report on the strawberry program, and interviews with key university staff.

Note: The university collected gross patent income in fiscal year 2010–11, distributed the net patent income to UC Davis in fiscal year 2011–12, and UC Davis distributed a portion of the net patent income to the strawberry program in fiscal year 2012–13.

* These amounts are estimates because the university does not calculate these expenses and revenues specifically for the strawberry program.

† UC Davis allocated $102,082 of other programs’ net income to the agricultural college, a portion of which was distributed to the strawberry program. In addition, UC Davis received an additional $71,716 of research share funding, a portion of which was also distributed back to the strawberry program.

‡ This represents an allocation to UC Davis’ general fund. According to UC Davis’ administrative budget and budget operations director (budget director), the provost oversees this funding and uses it to support the overall academic and organizational functioning of the campus.

§ According to the budget director, the provost uses this allocation to make various investments on campus. She stated that during our audit period, the provost used patent funds for safety improvements to the chemistry building, renovation of laboratory space for faculty in the College of Biological Sciences, and an investment in the mouse biology program.

II The agricultural college administers this fund, which is earmarked for strawberry research that is not exclusive to the strawberry program. For example, these funds may be used for research related to plant sciences, horticulture, plant pathology, and genetics, among other things.

Because some of UC Davis’ patents do not generate sufficient income to cover their own expenses, the income of profitable patents, such as those for strawberries, subsidizes the net expenses of unprofitable patents. As a result, UC Davis estimated that $746,881 of the $7 million in patent income that the strawberry program generated in fiscal year 2010–11 was used to subsidize the net expenses of other patents. The administrative budget and budget operations director of UC Davis’ Budget and Institutional Analysis Division (budget director) stated that it would not be in the best interests of the university to stop using profitable patents to subsidize patents that do not generate sufficient revenue to cover their costs because this would discourage researchers from applying for new patents. According to the budget director, all patents generate legal costs up front before they earn any royalties; thus, a patent may be unprofitable during its initial years even though it may prove to be profitable over its lifetime.

Because UC Davis only allocates a small portion of net strawberry patent income back to the program at the end of the distribution process, we believe that it could address the strawberry program’s recent loss of funding by increasing this allocation as necessary to adequately fund the program. However, the budget director believes that revising the distribution process in this way would lead to certain complications and is unnecessary. She stated that in order to allocate a larger portion of strawberry patent income to the strawberry program, the budget unit would need to reduce the funding of other research programs and entities on campus. She stated that, alternatively, the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences (agricultural college) and the Department of Plant Sciences (department) could allocate a greater share of their patent income to the strawberry program. In addition, she suggested that the strawberry program could submit budget requests or obtain new research grants to acquire additional funding. Nevertheless, we believe that UC Davis could ensure that the historically profitable strawberry program remains adequately funded by changing its distribution process to allocate more patent income back to the program.

University of Florida Patent Income Distribution Model

The University of Florida (Florida) distributes the patent income from its strawberry breeding program as follows:

- 10 percent to its licensing and patenting organization.

- 20 percent to its breeders and any cooperators (for example, other scientists that significantly assisted the breeders in the creation of a new cultivar).

- 70 percent to the Cultivar Development Research Support Program, which contains the strawberry breeding program. The funds are then distributed directly to Florida’s strawberry breeding program as follows:

- 100 percent of the first $50,000 of patent income earned per variety each year.

- 50 percent of the next $100,000 of patent income earned per variety each year.

- 33 1/3 percent of all patent income earned above $150,000 per variety each year.

Sources: Florida’s intellectual property policy and interviews with Florida staff.

Note: Florida applies this distribution model to the patent income that remains after deducting certain expenses, including patent filing fees and legal expenses. According to the assistant professor who oversees Florida’s strawberry breeding program, these expenses are almost negligible.

The University of Florida (Florida), which has conducted a strawberry breeding and selection program since 1968, demonstrates the feasibility of allocating strawberry patent income more directly to the strawberry program using the distribution model described in the text box. According to the assistant professor who oversees Florida’s strawberry breeding program, the strawberry breeding program’s share of patent income covered 100 percent of breeding operation expenses in fiscal year 2012–13. In addition, Florida distributes a significantly larger portion of total strawberry patent income back to its strawberry breeding program than UC Davis does. For example, in fiscal year 2012–13, Florida's strawberry breeding program generated $2.9 million in receipts of gross patent income and approximately 26 percent of that amount was distributed back to the strawberry breeding program. As discussed earlier, in fiscal year 2010–11, UC Davis earned $7 million of gross strawberry patent income and ultimately distributed $556,848, or roughly 8 percent, to its strawberry program. Similarly, in fiscal year 2011–12, UC Davis’ strawberry program generated roughly $7 million in patent income and UC Davis distributed $659,234, or approximately 9 percent back to its strawberry program. Even though the university paid the former breeders a higher royalty share than Florida does, if the university’s gross strawberry program patent income was reduced by the $2.2 million that it paid its former breeders, the percentage of remaining strawberry patent income that UC Davis allocated to the strawberry program would still be low compared to Florida. Specifically, UC Davis’ allocation of $556,848 of strawberry program patent income earned in fiscal year 2010–11 would constitute only 12 percent of the remaining strawberry patent income of $4.8 million.

In addition, we believe UC Davis should reassess the appropriateness of the current royalty rates charged to licensees. As we mentioned earlier, UC Davis discontinued two agreements that brought substantial revenue into the program. By discontinuing those agreements, UC Davis also eliminated the discounted royalty rates, which effectively increased royalty rates by 20 percent to 33 percent for sales to growers within California, elsewhere in the United States, and Canada. However, assuming that the university’s current distribution process and plant sales remain constant, the maximum increase to the royalties allocated to the strawberry program would be approximately $200,000—well short of the roughly $666,000 difference between the strawberry program’s revenues and expenses in fiscal year 2013–14.

Furthermore, despite the elimination of the discounts to the royalty rates, UC Davis’ undiscounted royalty rates remain lower than other institutions charge as illustrated in Table 3. UC Davis’ Innovation Access unit—the entity responsible for negotiating licensing agreements with nurseries and assessing royalty rates—should consider raising the strawberry program’s royalty rates. For almost all of the master licensees we reviewed, the university allows them to charge their sublicensees higher royalty rates than the rate floor that their licensing agreements set for international sales, so long as the master licensees split these additional profits equally with the university. However, the university does not have a similar mechanism in place for its licensed nurseries’ sales, so it has no assurance that these current rates are reasonable. According to the business development and intellectual property manager (intellectual property manager) of the Innovation Access unit, maximizing sales revenue by raising royalty rates to levels that could diminish stakeholder access to UC Davis’ strawberries may run counter to the public mission of the university to serve California agriculture. Although he asserted that the Innovation Access unit periodically analyzes the reasonableness of royalty rates, he was unable to demonstrate that the Innovation Access unit had performed any such analysis since 2007, when it last decided to increase rates. In that analysis, UC Davis compared its rates to those charged by industry peers, such as Florida, which used a similar royalty model. Based on that analysis, UC Davis raised royalty rates for certain licensees over the next three years, depending on the location of the sales.

| University of California, Davis (UC Davis) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discounted rates before September 1, 2013* (per 1,000 Plants) | Undiscounted rates effective September 1, 2013 (per 1,000 plants) | University of Florida (Florida) (per 1,000 plants) | Oregon State University (per 1,000 plants) | |

| Sales to growers within their respective state | $6.00 | $8.00 | $10.00† | $20.00 |

| Sales to growers within the United States (outside of their respective state) and Canada | 7.50 | 9.00 | 10.00 | 20.00‡ |

Sources: University of California (university) licensing agreements; UC Davis’ correspondence with its licensees; interviews with staff at UC Davis; Florida; Florida Foundation Seed Producers, Inc. (Foundation); the Florida Strawberry Growers Association (growers association); and Oregon State University; as well as their respective websites.

Note: This table does not include master licensees, which the university generally allows to charge their sublicensees higher royalty rates than the rate floor that their licensing agreements set for international sales, so long as these additional profits are split equally with the university.

* These discounted royalty rates were contingent upon the California Strawberry Commission and the nurseries fulfilling their financial obligations under their respective research agreements.

† According to the assistant professor who oversees Florida’s strawberry breeding program, this represents Florida’s full royalty rate, which was established by the Foundation, a support organization that manages Florida’s intellectual property, including strawberry varieties. However, Florida allows the growers association’s wholly owned sister organization, the Florida Strawberry Patent Service Corporation, to rebate growers association members 50 cents to $5 per 1,000 plants sold. In addition, the assistant professor also stated that while one older strawberry cultivar has a royalty rate of $6 per 1,000 plants sold, the newer varieties that make up the vast majority of Florida’s cultivar sales in the United States and Canada, have a $10 royalty rate.

‡ According to the senior licensing associate at Oregon State University, its licensing agreements do not allow nurseries to sell strawberry plants to growers outside of the United States.

Although UC Davis has options for adequately funding the strawberry program, at the time of our review, it had not made a final decision on how it will address the revenue it lost in fiscal years 2012–13 and 2013–14. In order to choose the best course of action, UC Davis should develop a budget for the strawberry program that accounts for the various changes to the program as it transitions to a new breeder.

The Department Has Not Always Developed or Used a Budget to Monitor the Strawberry Program

Because the strawberry program has recently lost a significant amount of funding and its financial reserves have declined, it is imperative that the department prepare a budget that details how the program will be funded in the future. However, the department has not consistently developed budgets for the strawberry program. According to the department’s chief administrative officer, the department prepared a budget for the period of October 2010 through January 2011. However, as shown in Table 4, it did not prepare another budget for almost two years, when it prepared a budget that covered the 14-month period of November 2012 through December 2013. The next budget that the department prepared covered the 18-month period of January 2014 through June 2015.

UC Davis’ 2013 Administrative Responsibilities Handbook (handbook) states that administrative officials should, whenever applicable, establish annual budgets to ensure sound financial management. However, UC Davis does not consider the handbook to be a formal policy, and the department’s chief administrative officer stated that the department is not required to prepare an annual budget for the strawberry program. She developed the budgets described above upon the request of one of the former breeders who also specified the time periods for the budgets. Nevertheless, we believe it is important for the department to consistently prepare annual budgets for the strawberry program, especially given the recent reduction in program revenues.

The budgets that the department prepared for the strawberry program included the projected salary and benefits expense for research staff and other support staff, travel expenses, and various supplies (the department accounts for non-capitalized equipment, contracted farm labor, and various other expenses as “supplies”). The budgets also included an estimate for the amount of patent and other income that would be allocated to the program and research contributions under the discontinued Non-California Discount Revenue Program (discount program). However, the strawberry program budgets have not included the costs of the former breeders’ salaries and benefits or all indirect costs because the university has separately funded the majority of these expenses. For example, the agricultural college and the university’s Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources have funded the salaries and benefits for the breeders using state general funds, federal funds, and other funds. Alliances and Services paid the breeders’ share of patent income in addition to the breeders’ salaries, which were funded and paid separately by the university.

The department’s most recent budget projected that the strawberry program would exhaust its reserves by the end of fiscal year 2014–15. As shown in Table 4, the department’s budget projected that the strawberry program would use the last of its reserves and would have a $104,000 deficit by June 2015. Even though the department identified this potential funding deficit back in January 2014 when it prepared the current budget, it has not yet completed an analysis of the strawberry program’s expected revenues and expenses for future years. The department chair explained that he is working with the new breeder to complete a strawberry program budget that includes this analysis by summer 2015.

| Budget Period | Budget | |

|---|---|---|

| February 2011–October 2012 | The Department of Plant Sciences (department) did not prepare a budget for the Strawberry Breeding Program (strawberry program) for this time period. | |

| November 2012–December 2013 | Actual beginning fund balance | $1,252,454 |

| Income | 979,066 | |

| Expenses: | 1,394,656 | |

| Salaries and benefits | 907,906 | |

| Supplies | 451,750 | |

| Travel | 35,000 | |

| Estimated ending fund balance | $836,864* | |

| January 2014–June 2015 | Actual beginning fund balance | $1,367,652 |

| Income | 450,000 | |

| Expenses: | 1,921,800 | |

| Salaries and benefits | 1,183,800 | |

| Supplies | 684,000 | |

| Travel | 54,000 | |

| Estimated ending fund balance | $(104,148) | |

Sources: Budget documents for the strawberry program and other information provided by the department’s chief administrative officer.

* The department underestimated the strawberry program's income for this time period, so the estimated ending fund balance was less than the actual.

Although the department identified this potential funding deficit, it did not perform any analysis to determine whether this projected shortfall would actually occur. When we compared the department’s budget to the strawberry program’s accounting records, we found that the program had a balance of $1.8 million at the end of fiscal year 2012–13, but that balance had declined to $1.1 million by the end of March 2015. This exceeded the department’s budget estimate that the program would only have a balance of $222,252 by the end of March 2015. According to the chief administrative officer, this variance occurred because the strawberry program’s expenses declined significantly after the two former breeders retired in November 2014 and the program’s patent income allocation was $174,000 higher than budgeted. However, UC Davis hired a new breeder who began working on the strawberry program in February 2015, so the reduction in strawberry program expenses may not be indicative of a continuing trend. The department chair stated that the department anticipates that once the strawberry program is back to full activity, its expenses will increase because crews will need to resume working at the test fields. In addition, he stated that the department is currently looking for a new test farm and he anticipates large upfront costs to prepare for this new location, including the purchase of new equipment and irrigation infrastructure.

The department cannot demonstrate that it uses these budgets to monitor the financial condition of the strawberry program. For example, it does not compare actual expenses to budgeted expenses by category (such as salaries, supplies, and travel) throughout the year. The handbook states that administrative officials must compare actual financial results to the budget regularly to ensure that expenses are consistent with the budget, that charges are appropriate, and that projected revenues are being realized. The handbook also states that administrative officials, or their designees, must determine the cause and take corrective action when actual financial results vary significantly from the budget. We believe this is an important practice that would help the department to ensure that the strawberry program operates in an efficient and cost‑effective manner. For example, the actual cost for supplies for the strawberry program exceeded the budgeted amount by $104,000, or 23 percent, for the period November 2012 through December 2013. However, the department’s chief administrative officer stated that the department did not compare actual expenses to budgeted expenses by category because it is not required to do so and because the strawberry program had a large surplus of funds remaining from prior years so it was unlikely that the program would run out of funding.

The department’s chief administrative officer stated that no individuals apart from her, the assigned account manager, and the former breeders were responsible for reviewing the financial condition of the strawberry program unless the program was in overdraft. The agricultural college conducts quarterly reviews of reports showing accounts in overdraft by over $100,000; however, according to its executive assistant dean, no such instances were noted for the strawberry program. In addition, the chair of the department stated that he would review the financial condition of the strawberry program if it were in overdraft, but this has never happened since he became chair in 2004. Nevertheless, we do not believe that the department and the agricultural college are adequately monitoring the financial operations of the strawberry program, particularly given the program’s declining fund balance.

Another factor that has made it challenging for UC Davis to effectively monitor the strawberry program is that until recently, its accounting system did not have a unique identifier to separately track the financial activities of the strawberry program. Rather, the department accounted for the activities of the strawberry program using organization codes assigned to the two former breeders, even though some of the funding in the former breeders’ accounts could be used by them to work on other projects and program activities at their discretion. By late February 2015, the department created separate financial organization codes for the new breeder and the strawberry program. According to the department’s chief administrative officer, in fiscal year 2015–16, the department plans to start using the strawberry program’s new organization code to account for all of the program’s activities. This will allow the department to separate the financial activities of the strawberry program from the financial activities related to the new breeder’s work for other programs or projects. Moreover, the lack of a unique organization code to track the strawberry program’s expenses made it difficult for UC Davis to provide accurate financial information in response to a request from the Legislature. As described further in the Appendix, UC Davis significantly understated the strawberry program’s revenues and expenses for fiscal year 2012–13 in its April 2014 report to the Legislature.

UC Davis Missed Opportunities to Collect All Strawberry Program Revenues

Under the terms of the strawberry program’s licensing agreements, UC Davis had opportunities to collect additional strawberry program revenues, but it chose not to do so. For example, UC Davis did not assess or collect late fees on royalty payments that were, in some cases, submitted months after they were contractually due. In addition, we identified discounts that UC Davis provided to master licensees and licensed nurseries, around the time the discount program’s agreements ended, without receiving any commensurate benefit. As discussed in the Introduction, the discount program provided these licensees with discounts on their sales to growers outside of California in exchange for an annual contribution to the strawberry program. UC Davis might have been able to collect additional revenue around the time the discount program ended; however, it set up the agreements that governed the discount program in a way that prevented it from doing so. After considering several factors and the advice of its counsel, UC Davis decided it would not attempt to collect those contributions. Finally, UC Davis’ lax oversight of the licensees’ sales reports provides little assurance that it is collecting all of the royalty revenues that it is owed.

Over a three-year period, UC Davis did not collect approximately $157,000 in interest charges from three licensed nurseries and a master licensee for late royalty payments. According to the intellectual property manager, the licensing agreements between the university and its licensees generally specify payment due dates and state that licensees must pay a late fee on late royalty payments. This late fee varies from 5 percent to 10 percent annual interest on the amount of the late payment, depending on the licensing agreement. We reviewed a selection of these licensing agreements, and all the agreements that we reviewed contained the terms regarding payment due dates and interest on late payments.

Of the nine licensees whose payments we reviewed during fiscal years 2010–11 through 2012–13, three licensed nurseries and one master licensee paid their royalties after the payment due date. However, UC Davis did not collect late fees from any of them. The three licensed nurseries accounted for roughly $4,000 of the uncollected late fees and the master licensee was responsible for the rest. Specifically, over these three fiscal years, we noted that the master licensee submitted almost all of its royalty payments after its contractual due date. As a result, UC Davis could have collected roughly an additional $153,000 in interest charges for these late payments. The intellectual property manager of UC Davis’ Innovation Access unit, which assists Alliances and Services with contacting licensees that are delinquent in paying royalties, stated that it was UC Davis’ practice not to collect late fees from licensees, as long as the licensees contacted the Innovation Access unit and made good faith efforts to submit their payments. According to the associate vice chancellor of Technology Management and Corporate Relations within UC Davis’ Office of Research, effective commercialization of research entails working with licensees in a manner that is supportive of their commercial and business needs rather than one focused on being punitive or directed towards extracting the maximum possible economic benefit from one or more licensees. Further, he stated that while UC Davis seeks to enforce contractual obligations, in practice it takes a fair, equitable, consistent, and good-faith based approach to working with its licensees. Nevertheless, by choosing not to pursue collecting late payment fees, UC Davis is missing opportunities to collect revenues that could be used to support the strawberry program.

With regard to the former discount program, we determined that the discount program’s agreements should have been better structured to protect UC Davis’ financial interests. Specifically, around the time the discount program ended, master licensees and licensed nurseries received a significant amount in discounts without providing a commensurate benefit to UC Davis and the strawberry program. As we discuss in the Introduction, the former breeders notified UC Davis in August 2012 that they were exercising their right to discontinue the funding arrangement and, in response to this request, UC Davis notified the master licensees and licensed nurseries that the discount program would be effectively terminated by December 31, 2012. When the discount program began, the former breeders and UC Davis agreed that the terms of the discount program’s agreements would govern the program’s termination. However, none of the agreements we reviewed contained any language that addressed winding down the discount program or the collection of final contributions. Specifically, the agreements were silent on whether contributions made before termination entitled a licensee to a discount on future royalty payments. Lacking specific guidance in the agreements, UC Davis provided some of its master licensees with discounts without collecting contributions in return. For example, UC Davis’ largest master licensee received discounts without any corresponding contribution for eight months, totaling roughly $206,000. Similarly, UC Davis provided licensed nurseries a total of $39,000 in discounts from July 2012 through September 2013 and received nothing in return.

Before proceeding with the termination of the discount program, UC Davis sought the advice of its counsel to confirm that its approach accounted for the legal complexities that this situation presented. UC Davis and its counsel considered many factors to determine the potential consequences of attempting to collect contributions. Specifically, UC Davis weighed the cost of a lawsuit with licensees that had long-standing relationships with the university against the benefit of the contribution amounts. As a result of these business considerations, UC Davis did not pursue collection. Although it is possible that UC Davis may have successfully collected contributions without having to provide the discounted royalty rate after program termination, its decision not to collect, based on advice of counsel and its business considerations, does not seem unreasonable. However, had the discount program’s agreements anticipated the issues associated with its termination and contained language to address those issues, UC Davis would likely have been able to avoid the resulting lost revenue.

UC Davis may also be missing out on royalties because it lacks an adequate process for ensuring that master licensees and licensed nurseries are accurately reporting their sales. The university’s licensing agreements that we reviewed contain language granting UC Davis the right to inspect the master licensees and licensed nurseries’ financial records and verify compliance with the terms of the agreements. However, according to the intellectual property manager, the Innovation Access unit has never conducted an audit of its master licensees and licensed nurseries to ensure that they accurately report their sales of licensed strawberry varieties and that they consequently are paying appropriate royalties to the university. Although the intellectual property manager agreed that the accuracy of sales is an area of potential risk, he asserted that performing audits of the licensees is not cost-effective. However, he was unable to provide any analysis to support his conclusion.

UC Davis employed a full-time field representative whose responsibility was, among other things, to monitor licensed nurseries. Specifically, the field representative was responsible for performing annual nursery site visits and conducting periodic surveys of the nurseries’ planted fruit acres. However, the intellectual property manager, who supervised the field representative, could not provide evidence that the field representative verified the nurseries’ sales reports or performed any of the required oversight activities. In addition, this field representative was working part-time from August 2012 until his retirement in August 2014. According to the intellectual property manager, UC Davis has hired a new field representative with an expected start date of June 2015. Nevertheless, without effective oversight activities such as regular reviews of licensees’ financial records, UC Davis cannot be certain that master licensees and licensed nurseries are accurately reporting sales of strawberry plants and that it is collecting all the royalties owed under the licensing agreements.

Recommendations

UC Davis should ensure that the strawberry program is adequately funded. To address the strawberry program’s recent loss of funding, the university should consider allocating more of the strawberry program’s patent income back to the program itself. In addition, UC Davis should regularly reassess the appropriateness of the strawberry program’s royalty rates charged to licensees and adjust the rates as needed to support the program.

The department should prepare a balanced budget for each fiscal year that details how it will fund the strawberry breeding program. In addition, it should begin comparing actual income and expenses to the budget periodically to ensure that the program is operating in a cost-efficient manner and is adequately funded.

To better enable it to effectively monitor and report the financial condition of the strawberry program, UC Davis should implement its plan to begin accounting for the strawberry program’s financial activities separately from those of the breeder in fiscal year 2015–16.

UC Davis should collect all late fees that its licensees owe.

If UC Davis considers providing future discounts on royalty rates, it should structure the agreements to ensure that it receives a commensurate benefit during the entire time that licensees receive discounts.

UC Davis should develop a risk-based audit plan to begin periodically reviewing the financial records of master licensees and licensed nurseries to ensure that they are accurately reporting all of their sales of licensed strawberry varieties and paying the university all the royalties it is entitled to. To encourage compliance, UC Davis should notify all master licensees and licensed nurseries that it will begin auditing the sales records of selected licensees.

We conducted this audit under the authority vested in the California State Auditor by Section 8543 et seq. of the California Government Code and according to generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives specified in the scope section of the report. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Respectfully submitted,

ELAINE M. HOWLE, CPA

State Auditor

Date: June 9, 2015

Staff:

Michael Tilden, CPA, Audit Principal

Nicholas Kolitsos, CPA, Audit Principal

Andrew J. Lee

Erin Satterwhite, MBA

Natalja Zvereva

Legal Counsel:

Stephanie Ramirez-Ridgeway, Sr. Staff Counsel

Amanda H. Saxton, Sr. Staff Counsel

For questions regarding the contents of this report, please contact Margarita Fernández, Chief of Public Affairs, at 916.445.0255.

Footnotes

2 This calculation excludes the impact of funding that UC Davis provides to pay for the indirect costs of the strawberry program. See footnote † in Table A for further information about UC Davis’ method for funding the program’s indirect costs.Go back to text