Use the links below to skip to the chapter you wish to view:

- Chapter 1—DHCS’ Failure to Ensure Timely Lead Testing of Children in Medi‑Cal Has Placed Them at Risk for Permanent Health Problems

- Chapter 2—CDPH Has Not Prioritized Its Mission to Prevent Lead Exposure

- Chapter 3—CDPH Has Not Demonstrated Effective Management of the Lead Prevention Program

Chapter 1

DHCS’ FAILURE TO ENSURE TIMELY LEAD TESTING OF CHILDREN IN MEDI-CAL HAS PLACED THEM AT RISK FOR PERMANENT HEALTH PROBLEMS

Chapter Summary

Millions of children in Medi‑Cal are not receiving the tests they need to determine whether they have lead poisoning and require treatment. DHCS’ data show that from fiscal years 2009–10 through 2017–18, 1.4 million of the State’s 2.9 million one‑ and two‑year‑old children enrolled in Medi‑Cal were not tested, and another 740,000 children missed one of the two tests they should have received. Some of these children reside in areas of the State with high occurrences of elevated lead levels, making the missed tests even more alarming. Nonetheless, DHCS has not effectively overseen the managed care plans with which it contracts to provide lead tests to children in Medi‑Cal. Specifically, DHCS does not require the plans to follow up with health care providers that do not report administering lead tests, and its method of determining whether managed care plans ensure that providers administer these tests is not effective. Although DHCS plans to implement a performance standard for lead testing and a financial incentive program to encourage lead testing, it has not yet done so. In the meantime, DHCS could direct managed care plans to inform providers immediately about children who have missed tests and the need to test them and report those tests.

DHCS Has Failed to Ensure That Health Care Providers Administer Required Lead Tests for Millions of Children

DHCS has not ensured that all children enrolled in Medi‑Cal receive the lead tests to which they are entitled. State regulations, with few exceptions, require health care providers to administer tests for elevated lead levels for one‑ and two‑year‑old children who are enrolled in Medi‑Cal. However, DHCS’ data show that from fiscal years 2009–10 through 2017–18, health care providers failed to administer all of the required tests for nearly three‑quarters of these children, as Figure 7 demonstrates. According to DHCS’ data, 1.4 million of the 2.9 million one‑ and two‑year‑old children in Medi‑Cal were not tested, and an additional 740,000 children missed one of the two tests they should have received during those years. These data—which, as we discuss below, may contain inaccuracies—suggest that the rate of eligible children receiving all of the tests that they should have was less than 27 percent.

Figure 7

Most Children in Medi-Cal Do Not Receive All Required Lead Tests

Source: Analysis of DHCS Management Information System/Decision Support System data.

DHCS has also failed to ensure that children are tested by age six. State regulations generally require that children in Medi‑Cal who are from two to six years old and who were not tested at age two be tested once their health care providers become aware of the missed tests. However, DHCS has not ensured that these children are tested, despite having the necessary information to make this determination. Moreover, it does not require managed care plans to notify health care providers that these children have not been tested. When we evaluated DHCS’ data related to children in Medi‑Cal who turned six years old during fiscal years 2015–16 through 2017–18, we found that of the 466,000 children who did not receive lead tests at age two, only 152,000, or 33 percent, received lead tests before age six, as required. Until these children are tested, their health care providers cannot know if they have elevated lead levels and need treatment.

Further, some of the children who did not receive the required lead tests reside in areas of the State with high occurrences of elevated lead levels. When we reviewed CDPH’s data on the location of children with elevated lead levels, we found that some geographic areas had a higher number of such children. For example, nine of the census tracts with the largest number of children less than age six that had elevated lead levels during fiscal years 2013–14 through 2017–18 are in Sacramento County, including the census tract with the largest number of such children in the State. Appendix B shows the 50 census tracts throughout California where we noted the highest numbers of children less than age six with elevated lead levels.

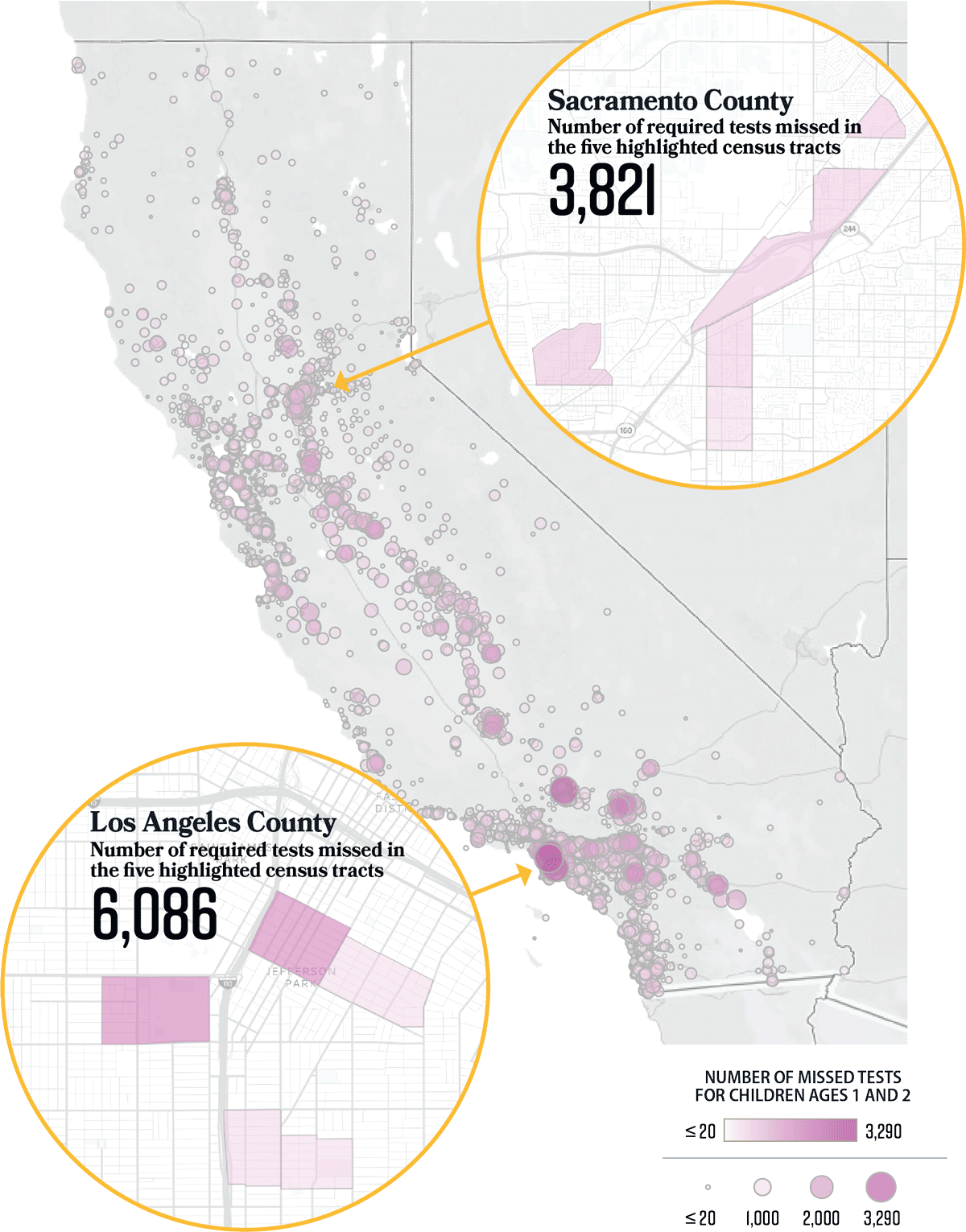

Figure 8 shows the locations of children in Medi‑Cal who, according to DHCS’ data, missed tests they should have received. When we compared DHCS’ data on children in Medi‑Cal at ages one and two years who had not received tests with CDPH’s data on the location of children less than age six with elevated lead levels, we found that some of the geographic areas with the largest populations of children with elevated lead levels also had a large number of children enrolled in Medi‑Cal who missed required tests. For example, in the Sacramento census tract described above, DHCS’ data show that children in Medi‑Cal at ages one and two years received just 392, or 35 percent, of the 1,135 lead tests they should have received, despite the fact that these children may be at a high risk for lead exposure. DHCS’ data show that in the 50 census tracts with the highest number of children less than age six who had elevated lead levels, children enrolled in Medi‑Cal collectively did not receive thousands of required tests at ages one and two.

Figure 8

Missed Lead Tests Are Concentrated in Certain Areas of the State

Fiscal Years 2013–14 Through 2017–18

Source: DHCS’ Management Information System/Decision Support System data.

Notes: We present an interactive dashboard for viewing additional detail on missed lead tests

at www.auditor.ca.gov/reports/2019-105/supplementalgraphics.html

To protect the confidentiality of the individuals summarized in the data, we included only census tracts with at least the following information for children ages 1 and 2 enrolled in Medi-Cal: 21 required tests, one missed test, and one completed test.

In a report provided to the Legislature, DHCS asserted that health care providers had not reported to it all of the lead tests that they had administered and that the testing rates were actually higher than its data show. According to DHCS, its data do not reflect a lead test if a health care provider administers it but only records an office visit. However, laboratories are required to report to CDPH all lead test results for blood drawn in California. Nonetheless, even after combining the lead test results that health care providers reported to CDPH with DHCS’ data, the resultant data still show that a majority of children did not receive all of the required tests. For example, in 2018 the two agencies reported that by combining their data for those children continuously enrolled in Medi‑Cal for 12 months during federal fiscal year 2015 they were able to identify additional blood lead tests that had been provided, which changed the percentage of children with an identified test from 40 percent to 49 percent for children aged 12 to 23 months and from 33 percent to 41 percent for children aged 24 to 35 months. The federal fiscal year begins October 1 and ends September 30.

To protect the confidentiality of the individuals summarized in the data, we included only census tracts with at least the following information for children ages 1 and 2 enrolled in Medi-Cal: 21 required tests, one missed test, and one completed test.

Our analysis of DHCS’ and CDPH’s data also demonstrates that even when CDPH’s data is included, more than half of children in Medi‑Cal did not receive the tests necessary to determine whether they need treatment. Specifically, we found that combining lead test data from CDPH with DHCS’ data identified another 8 percent of children who were eligible at one and two years old and received both tests during fiscal years 2009–10 through 2017–18. This analysis confirms that DHCS’ data alone do not include all of the lead tests children receive, leading us to question why DHCS has not yet implemented processes to ensure the accuracy of the information it collects. More importantly, this analysis also confirms that more than half of children did not receive the required tests. The two agencies also developed an estimate of the number of children in Medi‑Cal who turned three years old in federal fiscal year 2016, who were enrolled in Medi‑Cal all three years, and who received a single lead test by age three years. However, even under these more lenient criteria, the analysis showed that more than a quarter of the children in Medi‑Cal had not received a single lead test by the age of three.

DHCS Has Not Effectively Overseen the Managed Care Plans’ Provision of Lead Tests

DHCS has not demonstrated effective oversight of the managed care plans’ provision of lead tests. Although DHCS requires the managed care plans to report to it the lead tests they provide, DHCS does not use these data to identify the untested children whom the plans—which receive a set fee each month per person enrolled—are being paid to test. According to its monitoring chief, DHCS assumes that the managed care plans are ensuring compliance with lead testing requirements; however, it does not verify that the plans follow up with health care providers that do not report administering lead tests, nor do its contracts with the plans specifically require this sort of follow‑up. The monitoring chief stated that DHCS delegates oversight of this issue to the managed care plans but does not know how the plans ensure that health care providers are administering lead tests, other than through the reviews of provider records that it requires managed care plans to conduct.

The monitoring chief described the facility site review (FSR) process as DHCS’ means of oversight for ensuring children in Medi‑Cal receive blood lead tests. The FSR process involves the managed care plan reviewing the medical records of a small sample of patients at each primary health care provider site once every three years to verify whether those patients are receiving sufficient care, such as lead tests. However, this process does not adequately identify health care providers who are failing to administer childhood lead tests because it involves a sample of only 10 patients, which is not limited to young children. A DHCS medical program consultant acknowledged that the FSR process is not a comprehensive approach for determining whether children have received lead tests in part because it looks at so few records. In addition, even when managed care plans conduct an FSR and identify health care providers that have failed to administer required lead tests, the plans do not implement corrective actions unless those providers have also failed to administer a variety of other pediatric services.

Moreover, DHCS has not fully implemented a way to ensure that providers report the tests they administer. The underreporting we previously describe suggests that some providers lack motivation for administering and reporting tests. In 2018 the director of DHCS at that time stated that health care providers did not have sufficient incentive to report all of the services they administered. To create an incentive for providers not only to administer lead tests but also to report the tests they do administer, DHCS received approval in June 2019 to provide payments to providers for each lead test they report administering on or before a child’s second birthday. However, we are concerned with how long it will take to begin making these payments because as of September 2019, DHCS had not yet determined when it would begin making these payments.

It is unclear how long it will be until DHCS can evaluate the success of this program. DHCS plans to measure the program’s success by evaluating lead testing rates over time, but it does not currently use a performance measure for managed care plans’ reporting of lead testing, despite the effectiveness of such standards. Our March 2019 audit report titled Department of Health Care Services: Millions of Children in Medi‑Cal Are Not Receiving Preventive Health Services, Report 2018‑111, concluded that children receive services more often when DHCS imposes performance measures on managed care plans related to those services. In that report, we recommended that DHCS establish performance measures for children’s preventive services. Implementing a similar performance measure specific to lead testing may increase testing rates. According to its monitoring chief, DHCS is in the process of establishing a standard to assess the plans’ performance in providing lead tests and intends to work with the plans to hold them accountable after it assesses their progress in meeting this standard. However, the monitoring chief also stated that DHCS is several years away from assessing the managed care plans’ performance because it does not intend to complete development of the new performance standard for lead testing until 2021.

While it continues to develop its method of monitoring and enforcing lead testing requirements for managed care plans, DHCS could require them to inform health care providers of missed tests. As Figure 9 demonstrates, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) data show that California’s 36 percent lead testing rate for children enrolled in Medi‑Cal during federal fiscal year 2017 was below the national average of 45 percent for children enrolled in Medicaid programs nationwide in that year. CMS’s data represents a one‑year snapshot of the percentage of children ages 1 and 2 years continuously enrolled in Medicaid for 90 days or more who had at least one lead test. CMS’s numbers differ from ours because we looked at multiple years of data to determine whether children received all, one, or none of the tests that California requires. We reference CMS’s data here so that we can compare California’s performance with that of other states. Nonetheless, DHCS has not ensured that the health care providers assigned to children are aware that the children have not received the required lead tests.

Figure 9

California’s Lead Testing Rate Trails That of Most Other States

Source: CMS data for October 1, 2016, through September 30, 2017.

Several states with Medicaid lead testing rates in the top 20 percent of the nation, including Michigan and Wisconsin, performed targeted outreach by identifying children who were not tested and following up with health care providers who were not in compliance with testing requirements. For example, beginning in 2006, Wisconsin’s Medicaid staff collaborated with its state lead prevention program staff to send reports to Medicaid health care providers identifying their testing rates and the children in their care who had not received the appropriate blood lead tests. Wisconsin’s 2014 Department of Health Services’ report on childhood lead poisoning indicates that testing subsequently increased 29 percent, from almost 82,000 children tested in 2006 to more than 106,000 in 2010. The program ended after 2011 because of a loss of federal grant funding, and the number of children tested then decreased each subsequent year—dropping to about 84,000 by 2016. By requiring managed care plans to identify the health care providers for the children in Medi‑Cal who have not received all of their required lead tests and informing those providers of the tests that they need to administer, DHCS would reinforce testing and reporting requirements.

DHCS could also use the data that we summarize in Figure 8 to identify children who have not received the required tests and contact their families. Our March 2019 audit report concluded that DHCS was not meeting a requirement in federal law to perform annual outreach to the families of children who have not received preventive services, such as blood lead tests, to inform them of the benefits of preventive health care and explain how to obtain these types of services. Although DHCS stated at the time that it relies on the managed care plans to follow up with families of children who have not used preventive services, we found that the plans had not adequately communicated with these families. In that report we recommended that DHCS ensure that families of children who do not use preventive services are contacted annually. DHCS indicated in its six‑month response to that report that it is developing a process to follow up with the families of children who have not received preventive services over the course of a year.

Similarly, DHCS does not reach out to the families of children who have not received lead tests. DHCS’ monitoring chief was not able to provide a reason for why it does not do so. However, as we describe above, federal law requires DHCS to inform children or their families about the services that they are eligible to receive and also requires DHCS to provide lead testing as part of those services. Most importantly, because lead testing is the primary way to determine whether a child needs treatment for lead poisoning, DHCS’ failure to contact their families to follow up on missed tests leaves children at risk.

Recommendations

DHCS

Because of the severe and potentially permanent damage that lead poisoning can cause in children, DHCS should ensure that all children in Medi‑Cal receive lead tests by finalizing, by December 2020, its performance standard for lead testing of one‑ and two‑year‑olds. DHCS should use its existing data to assess the progress of managed care plans in meeting that performance standard and impose sanctions or provide incentive payments as appropriate to improve performance.

To ensure that families know about the lead testing services that their children are entitled to receive, DHCS should send a reminder to get a lead test for children who missed required tests. It should send this reminder in the required annual notification it is developing to send to families of children who have not used preventive services over the course of a year.

To increase California’s lead testing rates and improve lead test reporting, DHCS should, by no later than June 2020, incorporate into its contracts with managed care plans a requirement for the plans to identify each month all children with no record of receiving a required test and remind the responsible health care providers of the requirement to test the children. DHCS should also develop and implement a procedure to hold plans accountable for meeting this requirement.

Chapter 2

CDPH HAS NOT PRIORITIZED ITS MISSION TO PREVENT LEAD EXPOSURE

Chapter Summary

CDPH has not sufficiently identified areas of the State at high risk for childhood lead exposure, nor has it met its obligation to reduce the lead risks in those areas. CDPH’s data show that the number of children with elevated lead levels varies significantly by geographic area, but CDPH does not have an effective method of proactively reducing lead risks in the areas where elevated lead levels are most prevalent. Instead of addressing lead hazards before children are exposed to them, CDPH’s approach is to monitor lead abatement activities in the homes of children who already have lead poisoning. Further, CDPH largely delegates responsibility for addressing lead risks to local prevention programs—the county and city agencies we describe in the Introduction—but it does not sufficiently assess their performance. According to CDPH, it does not have the funds to perform proactive abatement of all regions of the State where children are at risk for lead exposure, yet it has not sought funding on behalf of the local prevention programs to accomplish abatement activities. Further, it could provide better information to the public about lead risks, particularly in properties being sold or rented.

CDPH Has Not Identified Areas Where Children Are at High Risk for Lead Exposure

Although state law requires CDPH to identify areas of the State where childhood lead exposure is especially significant, it had failed to complete this analysis as of October 2019. Specifically, since 1986, state law has required CDPH to identify geographic areas at high risk for lead exposure. However, CDPH last reported a list of high‑risk areas using data from 2015. A more recent state law requires that commencing March 1, 2019, and annually thereafter, CDPH must publicly post an updated analysis of the high‑risk geographic areas and other information related to the lead prevention program on its website. However, as we discuss in Chapter 3, CDPH has not met this deadline. Because it has not completed this analysis, CDPH lacks information on the locations where the risk of lead exposure is most significant.

In contrast to CDPH’s approach, Washington and Colorado have both created interactive maps that they publicly post detailing lead exposure risk by geographic area. They also use these maps to target their outreach and intervention efforts. If CDPH knew where the highest risk of lead exposure was, it could prioritize the resources it has to reduce the incidence of excessive lead exposure in those areas and better prevent lead exposure—the requirement established in state law and a goal described in the mission of CDPH’s childhood lead poisoning prevention branch.

In addition to an analysis of high‑risk geographic areas, state law also required CDPH, to the greatest extent possible, to post on its website by March 1, 2019, a list of the census tracts in which children tested positive for blood lead levels at rates that are higher than the national average and that are in excess of the level CDC considers elevated. In 2012 CDC set this level at 5 micrograms. CDPH informed us that in March 2019, it completed a draft version of a report addressing this requirement. However, despite the assertion of CDPH’s lead prevention program branch chief (branch chief) that CDPH intended to approve the draft report for public release as soon as possible, it had still not done so as of October 2019. The branch chief subsequently indicated that CDPH would publish the report by December 2019 and provided several explanations for the report's delay, including a lack of staff capacity, the vacancy of a branch chief, and the fact that the draft is currently under review by CDPH’s Office of Legislative and Governmental Affairs.

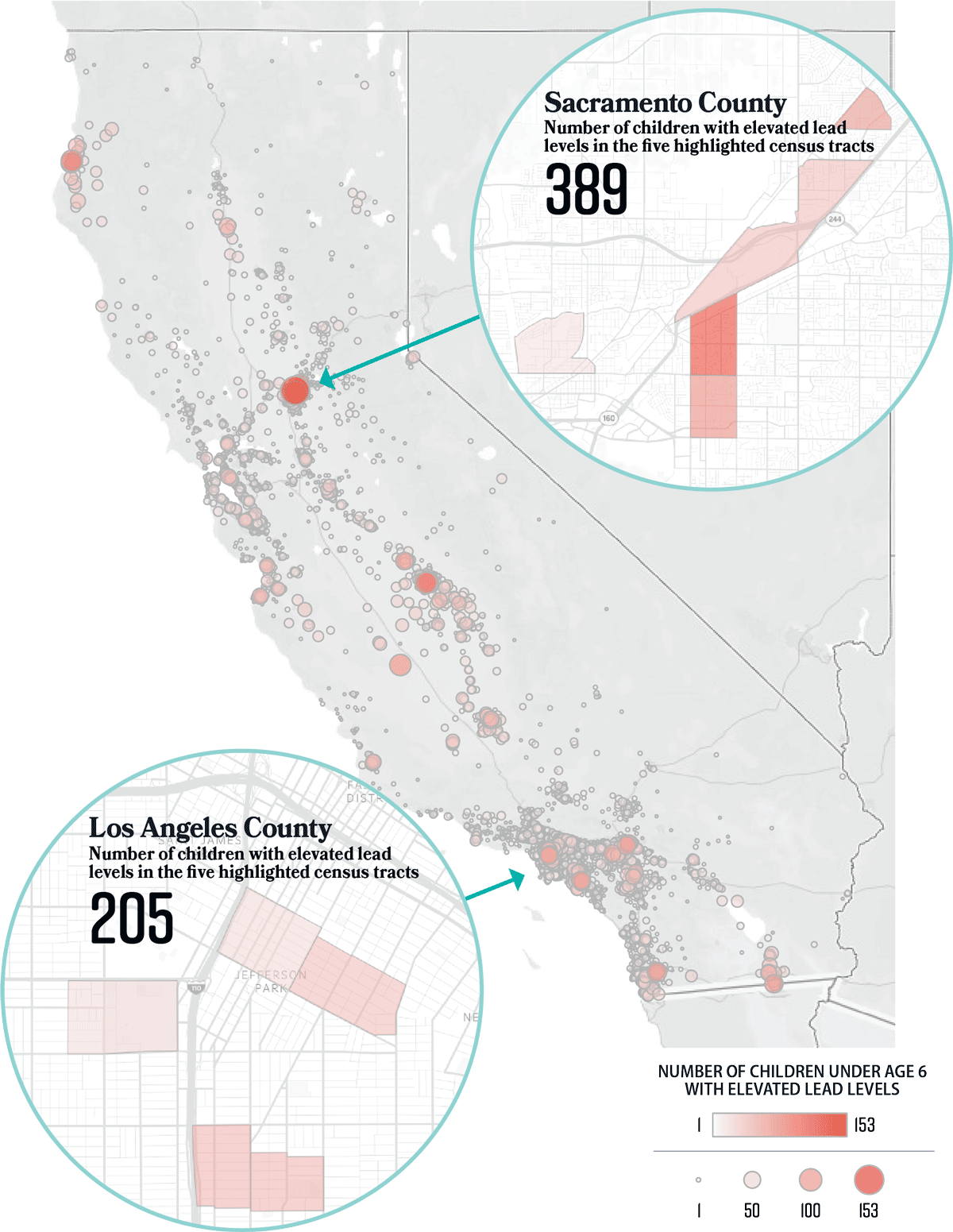

Our analysis of data from CDPH’s case management system shows that elevated lead levels vary significantly by geographic area. As Figure 10 shows, the data indicate that from fiscal years 2013–14 through 2017–18, the majority of children younger than six years old with tests showing elevated lead levels were concentrated in certain areas of the State. Specifically, half of the children with lead test results at or above 4.5 micrograms were located in just 15 percent of the State’s approximately 8,000 census tracts. This information suggests that CDPH could significantly contribute to the prevention of childhood lead poisoning by concentrating its efforts on the areas of the State where elevated lead levels are most prevalent, including taking steps to abate lead sources before more children are exposed to them.

Figure 10

Children With Elevated Lead Levels Are Concentrated in Certain Areas of the State

Fiscal Years 2013–14 Through 2017–18

Source: CDPH’s case management system data.

Notes: We present an interactive dashboard for viewing additional detail about children with elevated lead levels

at www.auditor.ca.gov/reports/2019-105/supplementalgraphics.html

To protect the confidentiality of the individuals summarized in the data and to present census tracts consistent with Figure 8, we included only census tracts with at least the following information for children ages 1 and 2 enrolled in Medi-Cal: 21 required tests, one missed test, and one completed test.

Nonetheless, CDPH’s approach is focused on eliminating sources of lead only for children who already have lead poisoning. Although this approach may prevent future cases of lead poisoning in those locations, it does not focus on prevention in the many other locations throughout the State where lead poses a risk. In fact, CDC’s advisory committee on childhood lead poisoning prevention concluded in 2012 that rather than just concentrating on activities to lower a child’s blood lead level, there is a need to reduce exposure to known sources, such as soil, dust, paint, and water, before they contribute to the child’s exposure. However, if CDPH does not know where these hazards are most prevalent and where children with elevated lead levels are concentrated, it is unclear how it will proactively mitigate lead exposure to protect California’s children from future lead poisoning.

CDPH Does Not Proactively Reduce Lead Exposure

CDPH’s approach to reducing lead in the environment is to take action after it determines a child has lead poisoning. In 1986 the Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Act established the requirement for CDPH to create a program of environmental abatement and follow‑up to reduce the incidence of excessive lead exposure. State law defines lead abatement as any set of measures other than containment or cleaning that is designed to permanently eliminate lead hazards or lead‑based paint in public and residential buildings. CDPH’s lead hazard reduction chief stated that CDPH’s approach to abating lead in high‑risk areas is to monitor abatement activities in the homes of children who have already been lead poisoned. However, this approach only prevents future poisoning in these same homes rather than addressing lead hazards before children are poisoned.

CDPH primarily delegates the responsibilities for addressing environmental lead risks to local prevention programs. However, CDPH’s contracts require abatement of lead hazards only for children who have lead poisoning. CDPH’s contracts give local prevention programs the option to apply for additional lead prevention program funding to develop and implement activities to prevent lead‑exposed children and at‑risk children from exposure to lead hazards. These optional activities include investigating locations where children are being exposed or have been exposed in the past, responding as necessary with appropriate enforcement actions, investigating tips and complaints about lead hazards, and documenting those high‑risk areas. CDPH’s lead hazard reduction chief informed us that CDPH does not require local prevention programs to perform proactive abatement but stated that their various outreach efforts reduce exposure in high‑risk areas. CDPH asserts that it is more efficient to perform outreach and education than to spend funds on physically abating lead in the environment. However, this approach relies on other individuals, such as parents and guardians, taking action based on the outreach and education. The extent to which individuals take such action is unknown because neither CDPH nor the local prevention programs we reviewed measure the effectiveness of their outreach activities in reducing the number of children with lead poisoning. Because the Legislature has given CDPH the responsibility to reduce the incidence of excessive childhood lead exposure, it should take steps to ensure that the local prevention programs’ activities are directly resulting in a reduction in the number of children with lead poisoning.

In addition, CDPH does not sufficiently assess the performance of local prevention programs. The branch chief stated that CDPH performs a comprehensive site review of each local prevention program, which involves its evaluating the program’s processes for carrying out contract requirements. CDPH’s policy requires it to conduct one site review of each local prevention program per contract cycle. However, as of August 2019, CDPH had conducted site visits of less than one‑third of the 50 programs, despite having already begun the third year of its three‑year contract cycle. Further, it had not conducted site visits at many of the local prevention programs for nearly five years.

Moreover, CDPH requires the local prevention programs to submit progress reports twice a year with updates on activities such as their outreach efforts, environmental investigations, and home visits to children with lead poisoning. However, CDPH’s review of these reports does not appear to sufficiently address performance because its feedback generally summarizes the information that the programs have provided without comparing their performance to a standard, and it rarely makes suggestions for improvement. For example, in assessing Los Angeles’s progress report on its activities in the first half of 2017, CDPH provided nine responses to Los Angeles evaluating its accomplishment of its contract goals. In six of those responses, CDPH merely summarized the information reported and thanked Los Angeles for its efforts. In two other responses, CDPH suggested that Los Angeles should repeat its description of activities performed for other goals but did not offer any insight on shortcomings. Without a more robust assessment of the performance of local prevention programs, CDPH cannot determine whether its method of delegating its responsibility to address environmental lead risks is effectively preventing lead poisoning.

CDPH Is Missing Opportunities to Facilitate Lead Abatement Throughout the State

Although CDPH asserted that it does not have the funds to perform proactive abatement of all regions of the State at risk for lead exposure, it could nevertheless better ensure that it uses existing funding effectively and apply for additional funding to perform abatement activities in the highest risk areas. For instance, a variety of federal grants and funding resources are available that can be used to offset the cost of abatement and other intervention efforts. CDC and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development have awarded grants to perform abatement and prevention activities, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) offers funding that some states use for lead abatement.

When we asked CDPH’s branch chief why CDPH has not applied for these funds, she stated that the amount of lead exposure prevented might not be worth the effort to manage such grants. Specifically, she explained that such grants would require a memorandum of understanding with DHCS, the State’s lead agency for interacting with CMS. In addition, she stated that it would take time for CDPH to create a team dedicated to lead hazard abatement and learn how to contract with private abatement companies. She further asserted that CDPH would be competing with local jurisdictions and that such funding would pay for abatement for only a tiny fraction of the State’s housing with lead risks. However, we do not find these reasons compelling. As we describe previously, more than half of the children with elevated lead levels are concentrated in 15 percent of the State’s census tracts. Moreover, as the agency overseeing lead poisoning prevention statewide, CDPH could efficiently facilitate the distribution of such funding by directly applying for it and passing it on to local programs, rather than having them expend resources competing against each other.

Unlike California, some states use proactive methods to facilitate lead abatement in the environment. For example, a number of states—including Massachusetts and Maryland—maintain publicly accessible online registries of residences built before 1978, the year lead paint was banned. These registries can provide information to property buyers and renters, such as whether and when a property was inspected for lead and the status of any identified lead hazards. This information allows the buyers and renters to better assess the risk of lead or the need for abatement. State regulations already require CDPH to collect lead inspection and abatement information. In fact, according to the lead hazard reduction chief, it receives such information on tens of thousands of properties every year, and it maintains this information in a database. Nonetheless, CDPH does not currently make this information available to the public, and it does not have plans to do so.

When we asked CDPH’s branch chief about the value of such registries, she agreed that they might encourage property owners to abate lead on their properties. However, she suggested that it is more useful to presume that a house built before 1978 has lead‑based paint, and she explained that the public can obtain the age of a home from the local tax assessor’s office or realtor websites. In addition, she noted that the data in the registry might be misleading because some level of lead always remains after abatement and because the data may not be current. However, the points she raises do not appear to outweigh the value to the public of such information. In addition, CDPH’s lead hazard reduction chief raised concerns that its database may contain personally identifying or medical information in cases where the inspection or abatement resulted from its case management efforts. If CDPH uses the information it already collects to create a registry, it will need to take steps to ensure that it does not make information available to the public that could be used to identify individuals in its case management system.

Federal law requires landlords and sellers of properties to disclose lead hazards for most residential properties built before 1978 unless they have been inspected and found to be free of lead‑based paint. However, according to California’s real estate disclosure guidelines we reviewed, this information is provided with the actual leases and contracts. As a result, potential renters and buyers may not have this information readily available when they are comparing their options. By providing this information to the public, CDPH would allow individuals to make more informed decisions about the potential risks of properties and to more accurately assess the possibility of future costs for abatement.

Recommendations

Legislature

To provide sufficient information to homebuyers and renters, the Legislature should require CDPH, by December 2021, to provide an online lead information registry that allows the public to determine the lead inspection and abatement status for properties. To accomplish this task, CDPH should use the information it already maintains only to the extent that it can ensure that it does not make personally identifying information, including medical information, public.

CDPH

To identify the highest priority areas for using resources to alleviate lead exposure among children, CDPH should immediately complete and publicize an analysis of high‑risk areas throughout the State.

To ensure that local prevention programs’ outreach results in a reduced number of children with lead poisoning, CDPH should, by December 2020, require local prevention programs to demonstrate the effectiveness of their outreach in meeting this goal. If the local prevention programs are unable to demonstrate the effectiveness of their outreach in reducing the number of children with lead poisoning, CDPH should analyze the cost‑effectiveness of other approaches, including proactive abatement, and require the local prevention programs to replace or augment outreach to the extent resources allow.

To offset the cost of mitigating lead exposure in the highest‑risk areas of the State, CDPH should seek out and apply for additional lead prevention funding as funding opportunities become available from CDC, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and CMS. To the extent necessary, CDPH should enter into a memorandum of understanding with DHCS to apply for and obtain this funding.

To better hold local prevention programs accountable for performing required activities, CDPH should, by June 2020, conduct direct oversight through site visits for each of the local prevention programs, and it should ensure that it continues to do so at least once per contract cycle. In addition, CDPH should use the local prevention programs’ biannual progress reports to assess local prevention programs’ performance and provide feedback on their strengths and shortcomings.

Chapter 3

CDPH HAS NOT DEMONSTRATED EFFECTIVE MANAGEMENT OF THE LEAD PREVENTION PROGRAM

Chapter Summary

CDPH has failed to effectively manage a number of aspects of the lead prevention program. For example, it has not met several legislative requirements that would allow it and health care providers to better identify children who need testing for lead poisoning. In addition, it has not effectively advocated for changes to a state law that makes it optional for laboratories to report information CDPH needs to match lead test results to children, thus causing a backlog of unprocessed lead test results. Finally, CDPH has continued to use outdated information in its formula to allocate funds to local prevention programs, resulting in differences in the services that some local programs are able to provide to children with lead poisoning.

CDPH Failed to Meet Several Recent Legislative Mandates

CDPH has failed to meet several legislative requirements that could improve the identification of children who need testing for elevated lead levels. For example, CDPH is overdue in producing a statutorily required report on the effectiveness of the lead prevention program. Further, it did not adhere to state law requiring it to develop regulations by July 2019 that include its determination of factors indicating that a child is at risk of lead poisoning, based on its assessment of the most significant environmental risk factors. In addition, CDPH’s failure to meet a requirement to notify health care providers in a timely manner of the risks and requirements related to lead poisoning may have resulted in children not receiving the follow‑up lead tests necessary to identify whether case management services have been effective or children require further services.

CDPH Has Not Produced a Required Biennial Report

CDPH has failed to meet several legislative deadlines related to childhood lead poisoning prevention and testing. As Table 3 shows, one of these requirements is to post on its website a biennial report describing the effectiveness of its case management efforts. According to state law, this report must include information on the number of children tested for lead poisoning, the number that received certain case management and environmental services, the identified sources of lead exposure, and whether those sources have been removed, remediated, or abated. However, CDPH did not produce the report by the March 2019 deadline. As we discuss in Chapter 2, the branch chief stated that CDPH was unable to meet this deadline because it lacked the staff to do so and its branch chief position had been vacant. However, given that CDPH had prepared a draft of the report by March 2019, it is unclear how those factors led to such a lengthy delay.

| Law Section | Legal Requirement | Missed Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| Health and Safety Code section 105285 | Develop regulations to include CDPH’s determination of risk factors for whether a child is “at risk” based on CDPH’s assessment of the most significant environmental risk factors. | July 1, 2019 |

| Health and Safety Code section 124125 | Post on CDPH’s website its analysis of the prevalence, causes, and geographic occurrences of high childhood blood lead levels. | March 1, 2019 |

| Post on CDPH’s website its analysis of the areas of the State that CDPH has identified and targeted where childhood lead exposures are especially significant. | ||

| Post on CDPH’s website an evaluation of its progress toward designing and implementing a program of medical follow-up and environmental abatement that will reduce the incidence of excessive childhood lead exposures in California. | ||

| Post on CDPH’s website an evaluation of its progress toward working with DHCS to advance lead testing for children enrolled in Medi-Cal. | ||

| To the greatest extent possible, post on CDPH’s website a list of the census tracts in which children test positive for blood lead levels at rates higher than the national average and that are in excess of CDC’s reference level.* | ||

| Health and Safety Code section 105295 | Post on CDPH’s website a biennial report on the effectiveness of its case management, including the following: • Number of children tested for lead poisoning and who received certain case management and environmental services; the identified sources of this lead exposure; and whether those sources have been removed, remediated, or abated. • Data by county and age on the number of children in Medi‑Cal and not in Medi-Cal who have received lead tests, and the number of children in Medi‑Cal who have not received lead tests. • Publicly releaseable data and information that CDPH compiles in accordance with the requirements of Health and Safety Code section 124125 above. |

March 1, 2019 |

| Health and Safety Code section 105286 | CDPH shall notify providers of the risks and effects of childhood lead exposure, as well as the requirement that children in Medi‑Cal and other at-risk children receive lead tests. | Effective January 1, 2019; no deadline specified in state law. |

Source: Review of state law, CDPH documentation, and interviews with CDPH staff.

* In 2012 the CDC set this level at 5 micrograms.

CDPH Could Improve the Identification of Children at Risk for Lead Poisoning by Finalizing Its Assessment of Environmental Risk Factors

A state law effective January 2018 required CDPH to develop regulations by July 1, 2019, identifying which factors health care providers must consider when determining whether children are at risk of lead poisoning, but it has not yet adopted these regulations. The law directs CDPH, when determining the risk factors, to consider a variety of significant environmental risks associated with lead exposure. The current regulation—which has not been updated since 2001—requires health care providers to assess only one environmental risk factor. Specifically, the current regulation requires health care providers to ask parents or guardians if their children live in or spend considerable time in a structure built before 1978 that has peeling or chipped paint or that has been recently renovated. However, many cases of lead poisoning among children are caused by sources of lead exposure other than lead‑based paint. Although lead paint was the most common source of lead exposure CDPH reported in its analysis of 188 cases of children poisoned by lead during fiscal year 2015–16, the analysis also indicates that 95 of these children were exposed to other sources of lead, such as cosmetics and traditional remedies (37 children) and imported foods and spices (six children). The current state regulation does not address these sources.

As Table 4 shows, other states address more risk factors in the questionnaires they use to assess whether children are at risk of lead exposure. By addressing only the age of a building—which aids in determining whether it might contain lead paint—California’s current regulation does not assist health care providers in identifying children exposed to lead through other sources. CDPH’s branch chief acknowledged the limitations of the current evaluation requirement and indicated that CDPH failed to meet the deadline for developing the new regulations because it lacked sufficient feedback from stakeholders. However, CDPH did not start soliciting this stakeholder feedback from medical providers until mid‑June 2019, less than a month before the deadline for developing the regulations. If CDPH intended to develop the regulations by July 1, 2019, it should have solicited this feedback from stakeholders several months earlier.

CDPH currently anticipates submitting its regulations to the California Health and Human Services Agency (CHHS) for review by March 1, 2020, eight months after the deadline. This delay has resulted in health care providers not having updated information on the current environmental lead risk factors that they need to consider, and possibly not detecting and treating lead poisoning in certain children. Moreover, even after it submits these regulations to CHHS, additional steps in the process are necessary before the regulations are finalized. For example, the draft regulations must be submitted to the State’s Office of Administrative Law to commence the formal rulemaking process. Consequently, the process will take more time than the March 2020 date suggests. However, when we asked CDPH when it anticipated that the regulations would be finalized, it did not share its time frame for completing these subsequent steps.

| Common Risk Factors for lead poisoning | California | New York | Texas | Illinois | Ohio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residency or time spent in an older building or one undergoing repairs | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Residency in or visit to a foreign country | X | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | X |

| Sibling or playmate with lead poisoning | X | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Placing nonfood items in the mouth | X | ✔ | ✔ | X | X |

| Proximity to adults who work with lead | X | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Proximity to current or former lead-producing facilities | X | ✔ | X | ✔ | ✔ |

| Using food, medicine, or dishes from other countries | X | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | X |

| Residency in a high-risk ZIP code | X | ✔ | X | ✔ | ✔ |

Source: State law; New York, Texas, Illinois, and Ohio Departments of Health.

CDPH Has Failed to Communicate the Importance of Lead Testing to Health Care Providers

Our review of CDPH’s data found that thousands of children did not receive follow‑up lead tests when needed. When children are identified as having elevated lead levels, CDPH requires providers to administer follow‑up tests to determine whether they have continued to be exposed to sources of lead even after receiving treatment. However, as Figure 11 shows, many children are not receiving follow‑up tests on time, or at all. Without follow‑up tests, CDPH and the local prevention programs do not know whether treatment has been effective and whether children continue to require care for lead poisoning.

Figure 11

Thousands of Children With Elevated Lead Levels Did Not Receive

Follow-Up Lead Tests or Received Them Late

Fiscal Years 2013–14 Through 2017–18

Source: Analysis of CDPH’s case management system data.

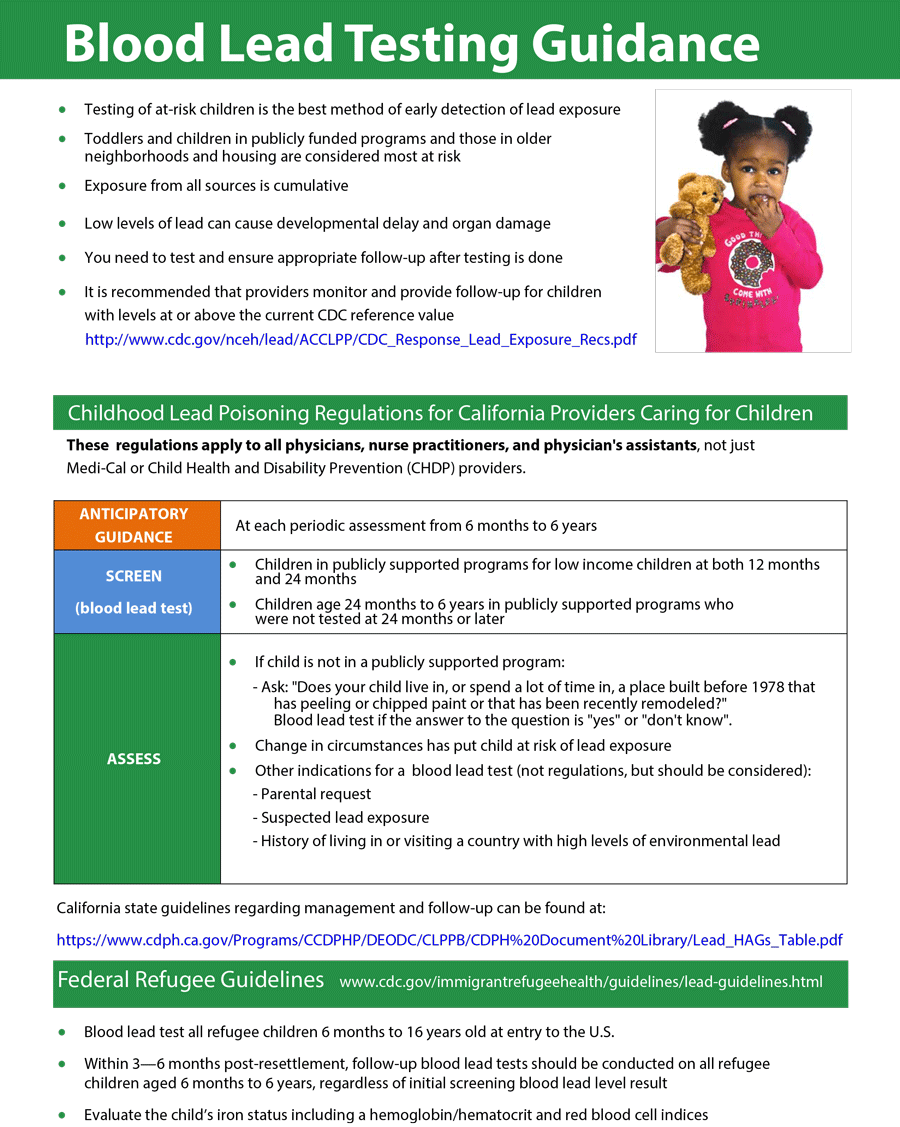

The Legislature passed a law effective January 1, 2019, that requires CDPH to inform all health care providers who perform periodic health assessments of children about the risks and effects of childhood lead exposure, as well as about testing requirements. Despite the fact that it already had the necessary information available when the law was passed in 2018, CDPH did not take action to provide that information to health care providers until August 2019. CDPH’s care management chief stated that CDPH took additional time to address the requirement because it was developing numerous ways to communicate with health care providers. However, we question CDPH’s apparent lack of urgency. In August 2019, CDPH submitted information for publication in the Medical Board of California’s fall 2019 quarterly newsletter, yet much of this information could have been included half a year earlier in its spring newsletter. Further, CDPH had other resources it could have used to communicate the required information directly to providers, including pamphlets it already produces, such as the one shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12

CDPH Publishes a Pamphlet Describing Childhood Lead Exposure Risks, Effects, and Testing Requirements

Source: CDPH pamphlet, published April 2016.

CDPH’s delay in informing providers of the risks and effects of lead exposure and the requirements to test for it may result in certain children not receiving appropriate care. State law requires health care providers to share the information from CDPH with parents and guardians, and the need to fulfill this requirement seems especially crucial given the number of parents and health care providers who fail to prioritize lead tests or do not follow lead testing requirements. Specifically, in 10 of the 40 cases of lead poisoning we reviewed, health care providers gave incorrect information about whether children needed follow‑up tests or administered incorrect tests. Further, parents declined to return for necessary follow‑up tests in 14 of the 40 cases. These errors and missed tests demonstrate the importance of CDPH promptly providing the required information. Not only will the information help educate health care providers on lead testing requirements, it will also assist those providers in communicating the importance of lead tests to parents.

CDPH’s Failure to Ensure That Laboratories Submit Adequate Patient Identification With Test Results Has Led to a Backlog of Unprocessed Cases

Despite a backlog of lead test results, CDPH has not sufficiently advocated for changes necessary to efficiently assign lead test results to children’s cases. CDPH must ensure that a child obtains appropriate case management when lead test results indicate the child has lead poisoning. When it receives test results from laboratories, it must link that data to existing cases in its case management system. Therefore, CDPH needs information that clearly identifies the child tested.

According to CDPH, the system currently uses identifying information for the test results, such as names, birth dates, and ZIP codes from addresses, to assign lead test results to new or existing cases. However, state law related to blood lead test reporting requires laboratories to report birth dates and addresses only if they have that information. If they do not have a child’s birth date, the law allows reporting the child’s age. Similarly, the law allows reporting a phone number when the address is not available. However, when labs do not submit addresses or birth dates, the case management system is sometimes unable to assign test results to children. If the system is unable to match new test results to existing cases, it cannot update the cases with new measurements of blood lead levels or close the cases when test results indicate it is safe to do so. Instead, it sends the records to a queue for manual processing by CDPH staff.

Since 2006 CDPH’s case management system has received more than 9 million test results, 9.6 percent of which required manual data processing. Test results without sufficient identifying information have contributed to the nearly 700,000 test results CDPH had queued in its system as of August 2019. Based on its 2018 average manual processing rate of 14 tests per day, CDPH would need an estimated 132 years to address this backlog, even if no additional test results were added. According to CDPH, it prioritizes manually reviewing and assigning to cases those test results in its queue that are above 3.3 micrograms. Our review verified that the lead test results remaining in the queue did not include any children with lead levels greater than this value. However, according to the chief of care management, this backlog has limited CDPH’s and local prevention programs’ ability to efficiently track cases and determine the need for follow‑up care, as manually searching for tests consumes a significant amount of staff time.

Although requiring more complete identifying information would help in assigning test results to new or existing cases, matching tests to cases can best be accomplished with a unique identifier, according to an epidemiologist at CDPH. She described various unique identifiers, such as Medi‑Cal identification numbers and medical plan identification numbers, that laboratories could include with their test results. State law allows laboratories the option of reporting additional identifying information to CDPH, and CDPH’s case management system has the capacity to collect such information. However, this law does not require such reporting. In addition, even though laboratories must review Medi‑Cal identification numbers for billing purposes, CDPH states that they rarely submit them with test results.

CDPH’s chief of its program evaluation and research section stated that CDPH is concerned that advocating for changes to state law might adversely impact the information it receives because laboratories and health care providers might advocate for less stringent requirements in response. Nevertheless, this information would improve CDPH’s ability to efficiently monitor the status of children with lead poisoning and determine their need for follow‑up care. Consequently, it is in the best interests of CDPH and the public for CDPH to prioritize advocating for legislative changes to require a unique identifier with test results from laboratories.

Poor data reporting by laboratories has also impeded CDPH’s ability to contact families of children who need services. CDPH requires contact information for children in order to provide additional services, such as home visits and environmental assessments. State law requires laboratories to report either phone numbers or addresses with test results. However, laboratories often do not submit sufficient information. Specifically, more than 325,000 records—or 12 percent of the lead tests that laboratories reported from July 2013 through June 2018 for children age 6 and under—lacked both addresses and phone numbers. Requiring laboratories to report both an address and telephone number would improve CDPH’s ability to contact the families of children with lead poisoning to deliver appropriate case management services. Further, it would provide information that CDPH could use to match lead tests to children’s records that do not have unique identification numbers.

CDPH’s Failure to Update Its Local Prevention Program Funding Allocation Methodology Has Led to Inequities in Allocations to Local Programs

CDPH’s inequitable methodology for allocating funds to local prevention programs has led to significant differences in the level of services those programs provide to children diagnosed with lead poisoning. Specifically, CDPH uses a formula based on outdated data, such as the number of children with lead poisoning in 2007. As a result, it has allocated to local prevention programs dramatically different amounts of funding per child with lead poisoning in their jurisdictions. According to CDPH’s administrative section chief, it generally bases funding for the local prevention programs on a number of factors, including an area’s number of low‑income children, its number of children in older housing, and the number of children with lead poisoning in the county in which the program is located. However, CDPH did not maintain documentation specifying how or when it calculated the proportions in which it distributes funds, so it had to recreate that analysis in response to our request for information.

Although the standard of care for case management of children with lead poisoning is the same regardless of where they live in the State, one of the local prevention programs we visited explained that its ability to provide home visits is limited by the amount of funding it receives. We found that during the contract period for fiscal years 2017–18 through 2019–20, the allocations to local prevention programs did not align with the numbers of children with lead poisoning for which the programs are responsible. For example, CDPH allocated the Riverside County local prevention program almost $550,000 in basic funding, while it allocated the Sacramento County local prevention program—which had twice as many children with lead poisoning—only $409,000. In ;fact, for local prevention programs with five or more such children, we found that the annual funding CDPH allocated varied from roughly $3,000 per child with lead poisoning to more than $30,000 per child with lead poisoning, based on CDPH’s counts of children with lead poisoning from 2015.

We observed differences in the levels of service provided by some local prevention programs because of funding levels, despite the fact that they are contracted to provide case management of children with lead poisoning according to the same criteria. For example, the Humboldt County local prevention program, to which CDPH allocated the equivalent of about $3,000 in basic funding per child with lead poisoning, performed home visits in only six of the 10 cases we reviewed, and it averaged 1.5 visits for those cases before their closure. It generally conducted a greater proportion of its outreach to the families of children with lead poisoning by telephone or letter rather than through home visits. In contrast, the Fresno County local prevention program—to which CDPH allocated the equivalent of more than $6,000 in basic funding per child with lead poisoning—performed home visits for every case we reviewed, and it visited each child eight times on average. Given that the suggested case management is similar for the lead levels of the children whose cases we reviewed in the two programs, we find the differences between the levels of service the children received troubling.

CDPH intends to continue using these funding allocations for contracts beginning in fiscal year 2020–21 despite the disparity in the services the local prevention programs have provided. According to CDPH’s administrative section chief, CDPH plans to continue using its current allocations because it anticipates upcoming changes to the lead prevention program as a result of the regulations it is in the process of completing to expand the definition of environmental lead hazard risk factors. However, he did not provide an expected completion date for these regulations. CDPH’s continued reliance on a formula that uses outdated information to allocate funding to local prevention programs has contributed to children receiving unequal levels of service. CDPH should instead create an allocation methodology that provides more equitable funding for these programs before it executes additional contracts with them.

Recommendations

Legislature

To support CDPH’s efforts to efficiently monitor lead test results, the Legislature should amend state law to require that laboratories report Medi‑Cal identification numbers or equivalent identification numbers with all lead test results.

To ensure that CDPH can contact the families of children with lead poisoning and has alternative information to match lead tests to the children’s records that do not have unique identification numbers, the Legislature should amend state law to require laboratories to report phone numbers and addresses with all lead test results.

CDPH

To better ensure that children with lead poisoning are identified and treated, CDPH should prioritize meeting legislative requirements related to these issues, including doing the following by March 2020:

- Finish developing the lead risk evaluation regulations and include in them multiple risk factors, such as those used in lead risk evaluation questionnaires in other states. It should also commence the formal rulemaking process.

- Provide guidance to health care providers about the risks of childhood lead exposure and statutory requirements related to lead testing.

To ensure a more equitable distribution of resources for treating children with lead poisoning, CDPH should, by June 2020, update its methodology for allocating funds to local prevention programs, including accounting for the most recent annual count of children with lead poisoning in each jurisdiction. CDPH should revise the allocations before each contract cycle.

We conducted this audit under the authority vested in the California State Auditor by Government Code 8543 et seq. and according to generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives specified in the Scope and Methodology section of the report. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Respectfully submitted,

ELAINE M. HOWLE, CPA

California State Auditor

January 7, 2020