Use the links below to skip to the section you wish to view:

- The Three Correctional Facilities Do Not Have Adequate Procedures to Ensure That They Provide Care to Victims of Gassing Attacks

- The Three Correctional Facilities Did Not Consistently Investigate Gassing Attacks in a Thorough and Timely Manner

- The Three Correctional Facilities Have Not Established Adequate Internal Processes to Prevent and Respond to Gassing Attacks

- Scope and Methodology

The Three Correctional Facilities Do Not Have Adequate Procedures to Ensure That They Provide Care to Victims of Gassing Attacks

Key Points:

• Santa Rita lacks effective procedures to ensure that it immediately informs victims of all available aftercare services—including medical evaluations for a communicable disease and workers’ compensation benefits.

• None of the three correctional facilities adequately informed victims of their right to request that inmates involved in gassing attacks be tested for a communicable disease.

• Although the correctional facilities had policies to provide counseling services to victims, they did not consistently document that they notified the victims of the availability of these services, nor did they document such notifications.

| Aftercare Practice | CIM | Men’s Central | Santa Rita |

| Medical treatment |

|

||

| The facility documented whether it informed the victims of their medical treatment options following a gassing attack. | 15/15 | 15/15 | Undetermined* |

| Victims’ responses indicated that they were informed of all medical options available following a gassing attack.† | 5/6 | 6/7 | 6/6 |

| Inmate testing |

|

|

|

| The facility documented whether it informed the victims of their right to request that the inmate be tested for communicable disease. | Undetermined* | Undetermined* | Undetermined* |

| Victims’ responses indicated that they were informed of their right to request that the inmate be tested for communicable diseases.† | 0/6 | 0/7 | 2/6 |

| Counseling |

|

|

|

| The facility documented whether it informed the victims of counseling options after a gassing attack. | Undetermined* | Undetermined* | Undetermined* |

| The facility documented that it sought out victims for counseling following a gassing attack. | Undetermined* | 7/15 | Undetermined* |

| Victims’ responses indicated that they were notified of the availability of counseling services.† | 4/6 | 2/7 | 2/6 |

Source: Analysis of policies and procedures and attacks that occurred at CIM, Men’s Central, and Santa Rita, as well as responses to our questionnaires by victims involved in 45 gassing attacks that we reviewed.

* The correctional facility does not specifically track this information, and we could not determine if it complied with its policies and procedures.

† A gassing attack can have multiple victims. We identified 55 victims of the 45 gassing attacks we reviewed and sent questionnaires to each victim. We received responses from victims of 19 attacks—six from CIM, seven from Men’s Central, and six from Santa Rita.

■ = Generally complied

■ = Partially complied

■ = Did not generally comply

Santa Rita Needs to Take Additional Steps to Inform Victims of the Medical Services Available to Them

As we discuss in the Introduction, gassing attacks pose a serious health risk to correctional staff because of potential exposure to communicable diseases. All three correctional facilities we visited have policies that require supervisors to encourage victims to obtain an immediate medical evaluation for infectious diseases following an attack. In addition, all three correctional facilities require supervisors to provide informational materials to the victims on available aftercare services, including forms on medical treatment options and communicable disease testing. State law also requires the correctional facilities to provide victims with information on their rights to workers’ compensation benefits, which can provide them with medical benefits if they are injured from a gassing attack. However, as indicated in Table 2, we found that Santa Rita did not track whether supervisors notified victims of their medical options following a gassing attack. Therefore, it was not clear if Santa Rita was notifying victims of all available medical services. In fact, we noted that victims in 12 of the 15 gassing attacks at Santa Rita did not seek medical evaluations. Moreover, Santa Rita could not demonstrate that victims in these 12 attacks filed for workers’ compensation benefits. In contrast, we noted that CIM and Men’s Central generally complied with their process to notify victims of their medical treatment options in all cases we reviewed.

We contacted the victims of the gassing attacks we reviewed to find out if the correctional facilities provided them adequate information on the medical options available to them. We received responses from victims of 19 attacks—six from CIM, seven from Men’s Central, and six from Santa Rita. Although we were unable to verify that Santa Rita consistently notified victims of their medical options, because of the lack of documentation noted above, most victims responding to our questionnaire indicated that they were informed of medical services following the gassing attack, as shown in Table 2.

Santa Rita acknowledged that it could improve its procedures and indicated it will review its notification procedures and make changes to document that it notifies victims of aftercare services. These changes will include a requirement that supervisors record that they have advised victims of their rights to aftercare benefits.

The Three Correctional Facilities Do Not Have Processes to Ensure That They Inform Victims of Their Right to Request That Inmates Be Tested for Communicable Diseases

The three correctional facilities are not fulfilling their responsibility to inform victims whether they were exposed to a communicable disease. State law requires that correctional facilities notify victims of a gassing attack when they have been exposed. At CIM, inmates coming into custody are tested for communicable diseases and it has the results of these tests available. However, CIM does not actively notify victims of gassing attacks whether the inmate involved was infected with a communicable disease. Citing federal medical privacy law, the chief medical officer at CIM asserted that he would not disclose to the victim whether the inmate involved has a communicable disease. However, federal medical privacy law provides an exception that allows correctional facilities to disclose an inmate’s medical information to a victim in these situations. In fact, in one of the 15 gassing attacks we reviewed, CIM was aware that the inmate had a communicable disease at the time of the March 2017 attack but it did not notify the victim of the exposure.

In addition to the one victim we noted in our testing, CIM failed to inform an additional victim that was attacked by the same inmate of the exposure to a communicable disease. When we raised this issue with CIM’s warden, he agreed that CIM did not have a process to notify victims of potential exposure. To address the problem, the warden implemented a policy in June 2018 that requires the chief medical officer to immediately notify a victim when an inmate involved in a gassing attack is known to be infected with a communicable disease. However, we are concerned that CIM may not effectively implement this new policy. Even though CIM notified the victims in August 2018 of the March 2017 exposure to a communicable disease, the chief medical officer at CIM confirmed he did not notify the victims until after one of the victims specifically requested this information in August 2018. However, the chief medical officer’s duty to notify the victim is not dependent on the request of the victim.

Although Santa Rita does not test inmates for communicable diseases when they come into custody, in two of the 15 cases we reviewed, the inmates had indicated to Santa Rita that they were infected. Santa Rita has a process to notify the victims of exposure to communicable diseases following a gassing attack when the victim requests notification, but it did not immediately notify the victims in either case following the attack in October 2017. Specifically, one victim requested the information at the time of the attack and Santa Rita provided the information. However, as indicated, Santa Rita’s duty under state law is to immediately notify a victim when it is aware an inmate is infected with a communicable disease and not to wait until the victim requests the information.

In the other instance, Santa Rita confirmed that it did not notify the victim and the commanding officer could not explain why the notification did not occur. In response to our concern, Santa Rita notified the other victim of the exposure in August 2018. Going forward, the commanding officer indicated that Santa Rita will revise its policies to notify a victim immediately if an inmate involved in a gassing attack is known to be infected with a communicable disease.

Moreover, Men’s Central could better inform victims when the inmate perpetrator has a communicable disease. It generally does not test inmates for communicable disease when they come into custody, citing the high volume of incoming inmates. However, Men’s Central indicated that it sometimes becomes aware that an inmate has a communicable disease. The public health nurse at Men’s Central indicated that she would inform victims that the inmate is infected, but that she may not always know who to inform unless the victim files a request to have the inmate tested. To address this problem, Men’s Central stated that it will modify its procedures to ensure that the public health nurse is notified of all victims in gassing attacks. In the 15 cases we reviewed at Men’s Central, its medical records indicated that none of the inmates involved in the gassing attacks were infected.

None of the three correctional facilities consistently documented whether their supervisors notified victims of their right to request that inmates involved in gassing attacks be tested. As the Introduction explains, state laws provide victims of gassing attacks with the right to request such testing. However, in our review of 45 gassing attacks, none of the three correctional facilities could provide documentation that any victims requested such testing. Because the three correctional facilities could not provide this information, we attempted to directly contact victims involved in the 45 cases we reviewed. Only two of the 19 victims who responded—both of them from Santa Rita—stated that the correctional facility informed them that they could request the testing. In response to our concerns, the three correctional facilities indicated they will update their policies to ensure that victims are notified that they can request that inmates be tested for communicable diseases immediately following gassing attacks.

The Three Correctional Facilities Did Not Consistently Document That They Informed Victims of Available Counseling Services

Each of the correctional facilities has counseling services available for victims following gassing attacks, but they did not consistently document that they notified these victims that they can use these services. Specifically, CIM and Santa Rita do not document whether they informed victims of counseling services. Both correctional facilities offer victims peer support counseling to discuss the incident with officers trained in critical incident responses, and they provide information and resources to victims to address concerns following the gassing attack. Both facilities also offer an employee assistance program, which allows employees to attend a number of sessions with a licensed counselor for any reason.

CIM policy requires officers to notify gassing attack victims of counseling options directly after an incident. Santa Rita, in contrast, reminds employees and supervisors about counseling options during annual trainings. CIM stated that CDCR policy does not require that it track whether it notifies victims of counseling services, but it asserted that counselors do contact victims after these incidents. Santa Rita also does not track whether victims are notified, asserting that its employees and supervisors are well aware of counseling services through policies and training. However, as indicated in Table 2, only six of the 12 victims at CIM and Santa Rita responded that they were aware of the availability of counseling services, suggesting that the correctional facilities’ current approaches to informing victims could be improved. If the correctional facilities do not document these notifications, they cannot ensure that all gassing attack victims are aware that they can seek counseling.

Men’s Central offers professional counseling from psychologists within the LASD, but it lacks a process to document when it offers the counseling services. LASD policy requires the jail to notify all gassing attack victims of the availability of optional counseling services through its internal Psychological Services Bureau (psychological bureau). Moreover, following a gassing attack, an operations sergeant has the discretion to require the employee to attend a counseling session. However, Men’s Central does not provide any guidance for its operations sergeants to determine when to require counseling, and those sergeants generally do not record their decision or if they notified the psychological bureau that an officer was a victim of a gassing attack.

Regardless of whether an operations sergeant determines that counseling is required, LASD policy also requires the psychological bureau to reach out to the victim to offer counseling services. However, we found that Men’s Central informed victims of the availability of counseling in only seven of the 15 cases we reviewed. As a result, we could not conclude that Men’s Central consistently refers victims to counseling. As indicated in Table 2, only two of the seven victims who responded to our questionnaire stated that Men’s Central made them aware that counseling services were available. In response to our concerns, Men’s Central agreed that it needs to better ensure that victims know about the available mental health services. It further stated that it plans to document when victims receive information regarding counseling services.

Recommendations

CIM

To ensure the health and safety of its employees and hold its supervisors accountable, CIM should revise its policies and procedures to require documentation that its supervisors are notifying victims of gassing attacks in a timely manner of the following:

• Their right to request that the inmates involved be tested for communicable diseases.

• The counseling services available to them.

To make certain that victims are aware of threats to their health, CIM should follow state law and ensure that its medical personnel immediately inform victims of gassing attacks of any evidence suggesting that the inmates involved have a communicable disease. It should further document that it has provided this information to victims.

Men’s Central

To ensure the health and safety of its employees and hold its supervisors accountable, Men’s Central should revise its policies and procedures to require documentation that its supervisors are notifying victims of gassing attacks in a timely manner of the following:

• Their right to request that the inmates involved be tested for communicable diseases.

• The counseling services available to them.

To make certain that victims are aware of threats to their health, Men’s Central also should follow state law and ensure that its medical personnel immediately inform victims of gassing attacks of any evidence suggesting that the inmates involved have communicable diseases. It should also document that it has provided this information to victims.

Santa Rita

To ensure the health and safety of its employees and hold its supervisors accountable, Santa Rita should revise its policies and procedures to require documentation that its supervisors are notifying victims of gassing attacks in a timely manner of the following:

• The medical services and workers’ compensation benefits available to them.

• Their right to request that the inmates involved be tested for communicable diseases.

• The counseling services available to them.

To make certain that victims are aware of threats to their health, Santa Rita should follow state law and ensure that its medical personnel immediately inform victims of gassing attacks of any evidence suggesting that the inmates involved have a communicable disease. It should further document that it has provided this information to victims.

The Three Correctional Facilities Did Not Consistently Investigate Gassing Attacks in a Thorough and Timely Manner

Key Points:

• At the three correctional facilities we reviewed, only 31 percent of gassing attacks from 2015 through 2017 resulted in convictions, in part because district attorneys declined to prosecute 44 percent of the cases.

• The three correctional facilities did not routinely collect all evidence necessary to prosecute gassing attacks. This resulted in district attorneys declining to prosecute four of the 45 cases we reviewed.

• Men’s Central and CIM extended their investigations of gassing attacks, significantly delaying consequences for the inmates involved. Only Men’s Central followed the state law requirement to test the gassing substance to confirm the presence of bodily fluids, which extended its investigations by nearly five months on average. Santa Rita did not refer four of the 15 cases we reviewed for prosecution, primarily because staff did not follow policies and procedures.

| Investigation and Prosecution Practice | CIM | Men’s Central | Santa Rita |

| Evidence collection |

|

|

|

| The facility collected physical evidence of the gassing substance. | 4/15 | 9/15 | 1/15 |

| The facility tested the physical evidence to confirm the presence of a bodily fluid. | 0/4 | 9/9 | 0/1 |

| Referral for prosecution |

|

||

| The facility referred gassing attacks to the district attorney. | 15/15 | 15/15 | 11/15 |

| Timeliness |

|

||

| The facility referred gassing attacks to the district attorney in a reasonable time frame. | 2/15 | 6/15 | 11/11 |

Source: Analysis of policies and procedures and attacks that occurred at CIM, Men’s Central, and Santa Rita.

■ = Generally complied

■ = Partially complied

■ = Did not generally comply

Few Gassing Attacks Have Resulted in Successful Prosecutions

To deter inmates from committing gassing attacks, the Legislature established criminal penalties for gassing attacks, as we discuss in the Introduction. However, as Table 4 shows, district attorneys were able to obtain a conviction in only 31 percent of the completed cases that the correctional facilities referred from 2015 through 2017. Ensuring prompt consequences is an important component of the correctional facilities’ processes to deter gassing attacks. If an inmate commits a gassing attack on an officer without repercussion, it conveys that committing gassing attacks may go unpunished.

| Outcome of Cases | CIM | Men’s Central | Santa Rita | Total | ||||

| Filed—convicted* | 9 | 39% | 66 | 33% | 5 | 15% | 80 | 31% |

| Filed—dismissed | 0 | 0 | 23 | 12 | 10 | 30 | 33 | 14 |

| Declined by district attorney† | 14 | 61 | 98 | 49 | 1 | 3 | 113 | 44 |

| Not referred by facility‡ | 0 | 0 | 11 | 6 | 17 | 52 | 28 | 11 |

| Subtotal–Completed cases | 23 | 198 | 33 | 254 | ||||

| Open cases | 3 | 43 | 8 | 54 | ||||

Source: Prosecution records from the three correctional facilities and the county district attorneys.

* Convictions include plea bargains for a conviction for another offense.

† The district attorney declined to prosecute gassing cases for insufficient evidence or prosecutorial discretion, among other reasons.

‡ The correctional facilities did not refer cases to the district attorney for lack of probable cause, among other reasons.

As Table 4 shows, district attorneys declined to prosecute a substantial number of cases that CIM and Men’s Central referred from 2015 through 2017, 61 percent and 49 percent, respectively. In contrast, the Alameda County District Attorney declined to prosecute only 3 percent of cases that Santa Rita referred during this same time frame. District attorneys have discretion to decide whether to prosecute gassing attacks. For example, one district attorney declined to prosecute a case that we reviewed because the inmate was in state prison serving time for another crime and the district attorney concluded that seeking an additional sentence for the gassing attack would not substantially affect the inmate’s current sentence. However, the correctional facilities were responsible for the district attorneys declining to prosecute some cases because they did not always collect sufficient evidence or conduct timely investigations, as we discuss in the next section.

None of the Three Correctional Facilities Consistently Collected Sufficient Evidence to Prosecute Gassing Attacks

Types of Evidence in Gassing Attacks

- Sample of the gassing substance

- The victim’s clothes that were struck with the gassing substance

- Victim, inmate, and witness statements

- Video and photographs of the attack

- The container used to throw or propel the gassing substance

Source: Review of policies of the three correctional facilities.

The correctional facilities we reviewed have not consistently met their responsibility to ensure that their officers gather sufficient evidence for district attorneys to prosecute gassing attacks. As the text box shows, officers can collect various forms of evidence at the scene of a gassing attack. Of the 45 attacks we reviewed, the correctional facilities referred 41 cases to district attorneys. However, those district attorneys declined to prosecute four of these 41 cases because the correctional facilities did not collect sufficient evidence. Further, as Table 4 indicates, district attorneys’ offices declined to prosecute a significant number of the total gassing attacks that CIM and Men’s Central referred. Based on our review, the three correctional facilities may be able to improve the conviction rates on their cases by more consistently collecting evidence.

None of the three correctional facilities regularly collected physical evidence, such as the gassing substance or the container used to throw the substance, yet state law requires correctional facilities to use every available means to investigate a gassing attack—including preserving and testing the substance to determine if it is a bodily fluid. However, the three correctional facilities generally did not collect physical evidence in gassing attacks involving an inmate spitting on an officer. Of the 45 cases we examined, 13 involved spitting—six at CIM, three at Men’s Central, and four at Santa Rita. In these types of attacks, the physical evidence could have included the officer’s uniform or the item used to clean the officer’s skin, such as a cloth or paper tissue. Although we acknowledge that preserving evidence of spitting can create challenges, state law still obligates correctional facilities to use all means possible to investigate gassing attacks.

The remaining 32 of the 45 gassing attacks involved a bodily fluid other than spittle. In these attacks, the investigation reports from the correctional facilities indicated that the inmate often used a container to throw the gassing substance at the officer, with the substance making contact with officer’s skin and uniform. The container and contaminated clothing can provide strong evidence that the inmate committed a gassing attack because the correctional facilities can test them to confirm the presence of bodily fluids. However, we found that the three correctional facilities often did not collect and retain physical evidence, such as the container or the contaminated uniform. For example, as shown in Table 3, CIM collected physical evidence in only four of the 15 gassing attacks we reviewed, despite having a memorandum of understanding with the San Bernardino County district attorney that requires CIM to preserve a sample of the substance that the inmate threw as well as the victim’s clothing. Further, the San Bernardino County district attorney chose not to file criminal charges in one of these four cases at CIM, specifically citing that CIM did not collect the evidence necessary to support prosecution of the crime.

Men’s Central collected physical evidence in nine of the 15 gassing attacks that we reviewed. In two of the six cases in which it did not collect physical evidence, the Los Angeles County district attorney declined to prosecute because of insufficient evidence. In both cases, the officers did not collect the container or the soiled uniform, and Men’s Central could not prove that the substance was a bodily fluid. Men’s Central agreed that its officers should collect the containers used to throw or propel the gassing substance and that it will provide training incorporating the need for staff to do so. Santa Rita did not collect physical evidence in 14 of the 15 gassing attacks that we reviewed and instead relied on video footage, photographs, and witness statements. Santa Rita had the lowest conviction rate and highest dismissal rate among the three correctional facilities, which could be in part because it does not collect physical evidence. However, the Alameda County district attorney declined to prosecute only one case that we reviewed and it did so only because the inmate faced other criminal charges.

Further, only Men’s Central follows the state law requirement to preserve and test gassing substances to confirm that they are bodily fluids. Of the 12 gassing attacks that did not involve spittle, Men’s Central collected physical evidence in nine of these cases and submitted a sample of the substance to the county crime laboratory for testing. In contrast, CIM stated that it does not test the gassing substance unless the district attorney requests it. However, CIM indicated that the district attorney did not request testing for any of the 15 cases that we reviewed. Nevertheless, CDCR stated that it expects CIM to collect physical evidence of the gassing substance to determine whether it is a bodily fluid. Santa Rita also does not test the gassing substance. The Alameda County district attorney indicated that it does not generally require Santa Rita to test the gassing substance before it files a case because the county crime laboratory has limited resources and the district attorney believes that other forms of evidence—video footage, photographs, victim testimony, and witness statements—often are sufficient to prosecute the crime. Santa Rita’s commanding officer acknowledged that the correctional facility should comply with the state law requirement to test the gassing substance and stated that it plans to do so for future gassing attacks.

Two Correctional Facilities Took an Unreasonable Amount of Time to Conduct Their Internal Investigations of Gassing Attacks

Men’s Central and CIM took significantly longer than Santa Rita to investigate the 15 gassing attacks that we reviewed at each correctional facility, as Figure 4 shows. Men’s Central’s investigations, including crime laboratory testing, took an average of more than seven months, CIM’s investigation took an average of more than three months, and Santa Rita’s investigations took an average of just 17 days. One of the reasons for Men’s Central’s longer investigations may be justified: it follows the state law requirement to submit gassing substances for laboratory testing, which prolongs the time it takes to refer cases to the district attorneys. However, Men’s Central and CIM unnecessarily extended the time they took to investigate cases, delaying resolution of the legal process. In fact, the district attorney declined to prosecute one Men’s Central case because of the length of the facility’s investigation. Nonetheless, as Table 4 shows, CIM and Men’s Central had higher conviction rates than Santa Rita, indicating that the additional time they took to investigate cases may have helped produce better results.

Figure 4

Testing the Gassing Substance Significantly Lengthens the Investigation

Source: Analysis of 15 gassing attacks that occurred at each of the three correctional facilities.

Note: Santa Rita does not require a detective to review the investigation. Neither CIM nor Santa Rita submit the gassing substance for testing. Further, Men’s Central collected and tested the gassing substance in nine of the 15 cases we reviewed.

Men’s Central took an average of more than seven months to complete its investigations of the 15 cases that we reviewed. In one extreme case, its investigation took 16 months. Part of this delay is attributable to its decision to follow state law by regularly testing gassing substances for the presence of bodily fluids, a process that took an average of nearly five months in the nine cases where it was conducted. As we previously discussed, CIM and Santa Rita have not tested the gassing substances and they rely on other forms of evidence.

Although testing the gassing substance created a delay at Men’s Central, it appears to have merit as the correctional facility had a conviction rate that was only slightly lower than CIM’s rate and significantly higher than Santa Rita’s rate. However, CIM and Santa Rita did obtain convictions without testing the gassing substances. Both the Alameda and San Bernardino county district attorneys told us that they generally do not require laboratory testing of the gassing substance if the other evidence gathered is compelling. Therefore, testing the gassing substance may be beneficial in obtaining sufficient evidence needed for a conviction, but it may not be necessary in all cases. For example, officers at Santa Rita wear body cameras, which combined with a victim’s testimony may provide clear evidence that the substance thrown was a bodily fluid. In other cases, an inmate may admit that the substance thrown was a bodily fluid, making testing unnecessary. If the correctional facility can obtain sufficient evidence of the gassing incident, a timely prosecution may promote the interest of justice rather than to delay prosecution because it is waiting for the results of laboratory testing.

Laboratory testing aside, Men’s Central still took nearly three months on average to investigate gassing attacks. The LASD jail investigations unit (investigations unit) investigates all crimes that inmates commit in Men’s Central, including gassing attacks, while the Men’s Central staff are responsible for notifying the investigations unit of the crime and initially collecting the evidence. We identified unreasonable and avoidable delays in nine of the 15 gassing attacks at Men’s Central that we reviewed, with one resulting in the district attorney declining to prosecute the case. Specifically, in that case the investigations unit did not deliver evidence of the gassing substance to the Los Angeles County crime laboratory until 10 months after the gassing attack occurred. Subsequently, because of the time needed to obtain laboratory test results, the investigations unit did not refer the case to the district attorney until 16 months after the incident. The district attorney declined to prosecute the inmate, citing that the inmate was now in state prison and that the delay in receiving the crime laboratory test results could provide the defendant with a viable defense of not receiving a speedy trial.

A sergeant from the investigations unit believes that staff members mistakenly put this evidence into storage instead of sending it to the crime laboratory. In another instance, the detective sent evidence to the crime laboratory three months after the attack occurred, but the investigations unit could not provide the reason for this delay. When the investigations unit finally referred the case for prosecution, the district attorney chose not to file charges because the inmate was in state prison and a conviction would not have substantially affected the inmate’s sentence. However, in both of these cases, the district attorney’s comments indicate that it may have chosen to prosecute the inmate had Men’s Central completed its investigation in a timelier manner.

In the remaining seven cases, the delays were either because of excessive time for Men’s Central to submit the case for investigation or for the detective to submit the case for prosecution, or both. Men’s Central stated that the delays were caused by multiple steps in the incident report approval process, and to address our concerns, it agreed to implement a general guideline of five days to forward incident reports to the investigations unit. The investigations unit sergeant asserted that the facts of each case impact how quickly detectives can refer cases to the district attorney, and that in recent years the investigations unit has dedicated more resources to improving the timeliness of investigations. Nonetheless, in an October 2017 investigation that we reviewed, the detective took nearly three months to refer the case to the district attorney because of delays in collecting witness statements, indicating that delays continue to be present even with additional resources.

Although state law requires correctional facilities to immediately investigate all gassing attacks, CIM took an average of 70 days to complete its investigations, which included preparing an incident report and collecting evidence. We identified unnecessary and avoidable delays in 13 of the 15 gassing attacks we reviewed. CIM noted that the delays in the investigations process were due to the multiple layers of review by various staff members in approving the incident report. In addition, when officers use force to subdue an inmate who commits the gassing attack, CIM incorporates an evaluation of the use of force by the officers into its investigation process. For the seven cases we reviewed that involved the use of force, this evaluation created a delay that averaged one month. Although CIM’s practice is to evaluate the use of force as part of its investigation, this evaluation is unrelated to whether the inmate committed a criminal act. Therefore, CIM’s current approach prolongs the investigation and delays any consequences for the inmate.

Santa Rita completed its investigations in a more timely manner than CIM and Men’s Central, but it did not refer four of the 15 gassing attacks that we reviewed to the Alameda County district attorney. For three of those four cases, Santa Rita did not refer them because staff did not follow its policies and procedures. Santa Rita did not refer the other case because the victim did not wish to file a criminal complaint. However, in response to our inquiry, the commanding officer at Santa Rita indicated that the correctional facility would review the four cases and refer them to the Alameda County district attorney for prosecution if the required elements of a crime are present.

Recommendations

Legislature

To shorten the time to submit cases of gassing attacks for prosecution, the Legislature should modify state law to provide correctional facilities the discretion to omit testing the gassing substance for the presence of a bodily fluid when the correctional facility, in consultation with its district attorney, finds that such testing is unnecessary to obtain sufficient evidence of a crime.

CIM

To ensure that it properly investigates gassing attacks and refers cases for prosecution, CIM should do the following:

• Implement procedures to ensure that it collects sufficient physical evidence and submits the gassing substance for laboratory testing, as state law requires.

• Develop goals for how long investigations should take and ensure that its officers adhere to these goals.

• Separate its evaluation of officers’ use of force from the investigation process it uses to refer cases to the district attorney.

Men’s Central

To ensure that it properly investigates gassing attacks and refers cases for prosecution, Men’s Central should do the following:

• Implement procedures to ensure that it collects sufficient physical evidence.

• Develop goals for how long investigations should take and ensure that its officers adhere to these goals.

Santa Rita

To ensure that it properly investigates gassing attacks and refers cases for prosecution, Santa Rita should do the following:

• Implement procedures to ensure that it collects sufficient physical evidence and submits the gassing substance for laboratory testing, as state law requires.

• Develop practices to ensure that it submits all cases for prosecution when probable cause of a crime exists. Further, it should expedite its review of the four cases that we identified, and if probable cause exists, submit those cases to the district attorney for prosecution.

The Three Correctional Facilities Have Not Established Adequate Internal Processes to Prevent and Respond to Gassing Attacks

Key Points:

• Two of the correctional facilities we visited—CIM and Santa Rita—have not taken full advantage of internal discipline procedures to deter and reduce gassing attacks. Although the two correctional facilities have procedures for using internal discipline to maintain control and promote desirable changes in inmate attitude and behavior, they only followed these procedures in 13 of the 30 cases that we reviewed.

• The three correctional facilities provide limited training to officers on how to prevent and mitigate the harm from gassing attacks, and as a result, their officers may not be sufficiently prepared to react to gassing attacks. Seven of 19 victims of gassing attacks at the three correctional facilities indicated that they were not aware of training available to them.

• CIM and Santa Rita do not actively track gassing attacks. However, such tracking could help them identify inmates who are repeat offenders, inmates whose characteristics make them more likely to commit gassing incidents, and other factors that create a higher risk of gassing attacks.

| Internal Discipline and Prevention Practice | CIM | Men’s Central | Santa Rita |

| Discipline | |||

| The facility documented whether it imposed appropriate disciplinary actions in accordance with its policies, including a consideration of the inmate’s mental health status. | 12/15 | 15/15 | 1/15 |

| Training and prevention | |||

| The facility trained its employees, at least annually, how to prevent and respond to gassing attacks. | Partial* | Partial* | Partial* |

| The facility has protective gear readily available for employees and requires its employees to wear it when dealing with potential or known inmate gassers. | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Victims’ responses indicated that they did not have concerns with the facilities’ training to prevent and mitigate gassing attacks.† | 4/6 | 4/7 | 4/6 |

| Tracking | |||

| The facility specifically tracked gassing attacks and attempted gassing attacks. | No | Yes | No |

Source: Analysis of policies and procedures and attacks that occurred at CIM, Men’s Central, and Santa Rita, as well as responses to our questionnaires of the victims involved in 45 gassing attacks that we reviewed.

* The facilities provide annual training on subjects such as the use of force and officer safety, but the training is not specific to gassing attacks.

† A gassing attack can have multiple victims. We identified 55 victims of the 45 gassing attacks we reviewed and sent questionnaires to each victim. We received responses from victims of 19 attacks—six from CIM, seven from Men’s Central, and six from Santa Rita.

■ = Generally complied

■ = Partially complied

■ = Did not generally comply

Two Correctional Facilities Often Did Not Take Disciplinary Action Against Inmates Involved in Gassing Attacks

CIM and Santa Rita are not taking full advantage of internal discipline to deter inmates from committing gassing attacks. As we discuss in the Introduction, internal discipline can include actions such as reducing inmates’ privileges, placing inmates into secured housing, and taking away credit time that inmates earn to reduce their sentence. All three correctional facilities have policies and procedures to use internal discipline to maintain control and promote desirable changes in inmate attitude and behavior. In addition, internal policies and state regulations for CDCR facilities require that correctional facilities evaluate the mental health and competency of an inmate when determining whether to impose internal discipline and what method to use. However, as shown in Table 5, CIM and Santa Rita imposed internal discipline in 12 and one, respectively, of the 15 incidents we reviewed at each correctional facility. For CIM, five of the 12 incidents included inmates for whom it believed it was appropriate to waive internal discipline due to the inmates’ mental health condition. Nonetheless, because these two correctional facilities did not impose internal discipline in the remaining cases, this may result in inmate perpetrators not receiving any consequences for their crimes. In fact, as Table 4 shows, from 2015 through 2017 district attorneys obtained convictions for only 39 percent and 15 percent of gassing attacks at CIM and Santa Rita, respectively. CIM acknowledged that the three cases in which it did not impose internal discipline were the result of staff not following policies and procedures. To address this problem, CIM has developed a tracking system to ensure that it holds inmates accountable. Santa Rita indicated that it does not always impose internal discipline for gassing attacks because it relies on criminal prosecution instead. Specifically, the commanding officer of Santa Rita indicated that discipline is not always the most effective way to prevent and deter gassing attacks because inmates who commit these attacks often are already in segregated housing and they have lost their privileges. Nonetheless, we noted that some inmate attackers at Men’s Central were on similar restrictions, yet it imposed discipline more often than Santa Rita.

In contrast to CIM and Santa Rita, Men’s Central consistently imposed internal discipline or determined it was appropriate to waive discipline because of the inmate’s mental health condition for each of the 15 gassing attacks that we reviewed. The discipline that Men’s Central imposed was generally the loss of inmate privileges and placement in segregated housing. For the inmates for whom it waived internal discipline, Men’s Central transferred them to segregated housing in another of its correctional facilities for mental health observation. According to Men’s Central’s policy, it consistently imposes internal discipline to make sure it holds inmates accountable for their actions, to maintain order, and to protect its staff.

Although the Three Correctional Facilities Have Implemented Certain Preventative Measures, Additional Training Could Better Prepare Officers to Respond to Gassing Attacks

To mitigate the harm of gassing attacks, the three correctional facilities typically had available protective equipment, such as facemasks or hand‑held shields, to block items thrown by inmates even though this type of equipment cannot protect against all gassing attacks. CIM and Men’s Central provide officers access to protective gear, such as shields or helmets, when they need it. Santa Rita requires employees to use a protective door shield that it developed, known as a Bio‑Barrier, as pictured in Figure 5. It also requires, at a minimum, a face shield and gloves when moving or interacting with inmates who have committed previous gassing attacks. All of the correctional facilities also make available full‑body biohazard suits. During our review, we inspected each correctional facility’s inventory of protective equipment and found that the gear was available to the officers. Nevertheless, in one of the incidents we reviewed at CIM, the victim stated that he did not wear a face shield because they were unavailable. Gassing attacks often occur without warning, meaning that officers may not be able to put on protective gear before the attack. An officer’s use of protective gear can be effective in mitigating the effects of gassing attacks, but only when the officer can access the gear and decide to use it before an attack.

Figure 5

Preventative Tools to Mitigate Gassing Attacks

Source: Photographs and policies provided by the three corrections facilities and photographs taken by audit staff.

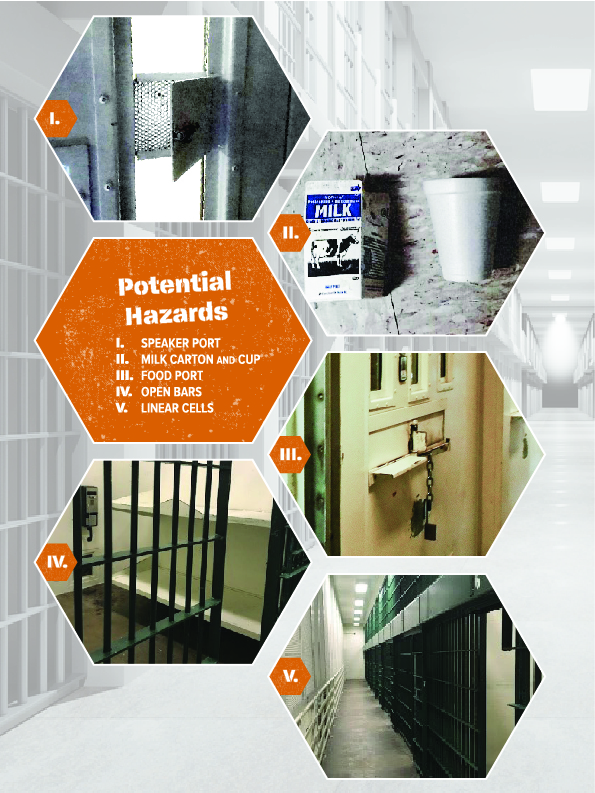

Officers may need protective equipment as the infrastructure at CIM and Men’s Central can increase the risk of gassing. Most of the holding areas in Men’s Central, and some at CIM, are either open‑bar cells or dormitory-style housing, as Figure 6. In this type of housing, inmates can throw substances at officers through the bars of their cells. Both correctional facilities mitigate these infrastructure problems by housing inmates who are likely to commit gassing attacks—those who have made threats or previously committed attacks—in secured housing. Secured housing cells, which contain a single individual, include hard‑door cells with windows to see the inmate and a port to provide meals and personal supplies or to handcuff inmates, as Figure 5 shows. However, CIM has 72 secured housing cells in its outpatient housing unit in comparison to its 3,500 inmates. Men’s Central can house only up to 54 inmates in cells with preventive measures, and it houses the vast majority of its 4,200 inmates in open‑bar cells or dormitories. In contrast to CIM and Men’s Central, Santa Rita has 1,103 hard‑door cells throughout the facility, and these afford better protection for officers against gassing attacks. Nevertheless, secured housing cannot eliminate gassing attacks. For example, 11 of the 15 gassing attacks that we reviewed at CIM occurred in its outpatient housing unit, which is equipped with hard‑door cells and ports.

According to its sergeant in charge of logistics, Men’s Central is unable to modify all cells with preventive measures due to the prohibitive cost of modifying its aging facility. In part to address the infrastructure concerns with this correctional facility, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors approved in June 2018 a $2.2 billion plan to replace the Men’s Central facility by 2028 with a modern correctional facility.

Although not a formal policy, CIM and Santa Rita place “gasser” tags on the cells housing inmates who have previously committed gassing attacks in order to warn officers of their dangerous behavior. This facility practice may minimize the chances of the inmate successfully committing additional gassing attacks. In our review of 15 cases at CIM, we identified one case in which CIM did not place a “gasser” tag on the cell of an inmate who had committed a gassing attack. As a result, when the inmate committed another gassing attack eight days later, the victim had no warning about the threat that this inmate posed.

Figure 6

Potential Hazards That Enable Gassing Attacks

Source: Photographs provided by the three correctional facilities and interviews with their staff.

Each facility provides training to officers, but that training is about subjects such as the use of force or officer safety and not specifically about gassing attacks. For example, CIM provides annual training to officers on the use of force and the danger of exposure to blood‑borne pathogens. However, the correctional facility was unable to demonstrate that any of the training is specific to preventing and mitigating gassing attacks. Two of the six victims we spoke to at CIM indicated that they had not received training to help protect themselves from a gassing attack. Additionally, the training primarily occurs when employees begin working at the facility rather than annually, which would ensure that all staff receive a refresher on best practices.

New employees at Men’s Central receive training on gassings attacks, which describes the elements of a gassing incident and how to respond after an incident occurs. LASD’s custody training and standards bureau also sends out instructional bulletins monthly to all staff, although it has not issued a bulletin specific to the topic of gassing since 2015. However, three of seven victims of a gassing attack at Men’s Central reported that they had not received any training or information about how to protect themselves in the event of a gassing. A fourth respondent stated that the information was available but that it was not easily accessible.

Similarly, two of the six victims at Santa Rita indicated that they had not received training to help protect themselves from a gassing attack. The commanding officer at Santa Rita indicated that additional training dedicated to gassing is unnecessary because existing training, including new employee training, covers all assaults to staff—including gassing attacks. However, he stated further that Santa Rita does not have training for its officers specifically for how to investigate gassing attacks. Such training would be helpful because some of the reports we reviewed concluded that a gassing attack had occurred even though the substances did not make skin contact. State law requires the bodily fluid to touch the skin to be a gassing attack, so officers may not be sufficiently informed on what a gassing attack involves. By providing annual training specific to gassing, the three correctional facilities could help officers be more prepared to prevent and respond to gassing attacks.

CIM and Santa Rita Should Track Gassing Attacks to Identify High‑Risk Situations and Deter Repeat Offenders

CIM and Santa Rita are not specifically tracking gassing attacks, and therefore they are missing an opportunity to analyze those attacks and reassess their current procedures to better ensure the health and safety of their officers. State laws and regulations do not require correctional facilities to track gassing attacks. Nevertheless, doing so would help the correctional facilities address the aftercare, investigative, and disciplinary concerns that we discuss throughout this report. Moreover, the correctional facilities could use knowledge from the trends and common characteristics that can become apparent from tracking gassing attacks to streamline their prevention efforts, including the systematic identification of inmates who commit gassing attacks and inmates who are repeat offenders. We found that 22 of the 45 gassing attacks (49 percent) that we reviewed at the three correctional facilities involved repeat offenders. This count included seven cases at CIM, nine at Men’s Central, and six at Santa Rita. Repeat offenders at Santa Rita committed 16 of the 25 gassing attacks (64 percent) in 2017.

A correctional facility’s tracking of gassing attacks should result in information that is consistent and readily accessible, which is not currently the case at CIM and Santa Rita. For example, CIM records all incidents involving inmates, including incidents of gassing attacks, in the CDCR’s Daily Information Reporting System database (database). However, this database cannot produce reports that are specific to gassing attacks without significant manual analysis. The warden indicates that CIM has not needed to separately track gassing attacks, but rather it tracks them with other battery offenses against officers. Santa Rita must consult three separate databases—two that the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office maintains and one countywide criminal database—to obtain information about gassing attacks at its facility, making it difficult for Santa Rita to readily analyze gassing attacks. Santa Rita indicated that it records information about attacks in general on correctional staff in its internal tracking system, but this system does not specifically track gassing attacks. Santa Rita also indicates it is already aware of which inmates are repeat offenders and where gassing attacks are likely to occur. Nonetheless, by systematically tracking gassing attacks, CIM and Santa Rita would have more information available to analyze how best to provide for the health and safety of their officers.

In contrast to CIM and Santa Rita, Men’s Central began tracking gassing attacks in 2015 to obtain a better understanding of why an increase in these attacks was occurring. Men’s Central tracks data to identify common characteristics of gassing attacks—including the incident location, time, and date; whether the incident involved repeat offenders or victims; and the types of inmates involved, such as high‑security individuals, those from the general population, and those suffering from mental illness. It uses this information to review procedures to prevent future attacks.

Recommendations

CIM

To ensure the health and safety of its officers when interacting with inmates, CIM should do the following:

• Maintain a sufficient supply of preventative equipment that is available to its officers and staff in all locations where gassing attacks can occur.

• Develop a policy regarding the placement of “gasser” tags on the cells of inmates who have committed or attempted to commit a gassing attack.

• Provide annual training that is specific to preventing and responding to gassing attacks.

To ensure that it is able to identify high‑risk situations and deter repeat offenders, CIM should specifically track all gassing attacks and use the tracking data as a tool to prevent future gassing attacks.

Men’s Central

To ensure the safety of its staff, Men’s Central should provide annual training that is specific to preventing and responding to gassing attacks.

Santa Rita

To better prevent gassing attacks and promote desirable changes in inmate attitude and behavior, Santa Rita should follow its policy and pursue appropriate internal disciplinary actions—including consideration of the inmate’s mental health and competency when determining whether to impose internal discipline.

To ensure the health and safety of its officers when interacting with inmates, Santa Rita should do the following:

• Develop a policy regarding the placement of “gasser” tags on the cells of inmates who have committed or attempted to commit a gassing attack.

• Provide annual training that is specific to preventing and responding to gassing attacks.

To ensure that it is able to identify high‑risk situations and deter repeat offenders, Santa Rita should specifically track all gassing attacks and use the tracking data as a tool to prevent future gassing attacks.

Scope and Methodology

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee (Audit Committee) directed the California State Auditor to review the policies, procedures, and practices in place to protect the health and safety of correctional staff who are subject to gassing attacks at three correctional facilities: CIM, Men’s Central, and Santa Rita. Table 6 lists the audit objectives and the methods we used to address them.

| Audit Objective |

Method

|

|

| 1 | Review and evaluate the laws, rules, and regulations significant to the audit objectives. | We reviewed relevant state laws, regulations, and other background materials applicable to gassing attacks at the three correctional facilities we visited. |

| 2 | Determine how the prison and jails track, document, and investigate gassing attempts and incidents perpetrated by inmates on employees. | We interviewed personnel and reviewed policies and procedures used for tracking, documenting, and investigating gassing attacks at each of the correctional facilities. |

|

3

|

To the extent possible, determine the magnitude of the gassing problem at the prison and jails since 2009 by identifying the following: | To address this objective, we performed tasks described below at the three correctional facilities: |

|

a. The number of gassing attempts and gassing incidents that occurred each year, including:

b. The number of staff members who, following a gassing incident, informed their employer that they contracted a disease as a result of the incident. c. Whether there was a correlation between the number of gassing attempts and incidents, and the prison or jail’s infrastructure, layout, or population overcrowding. |

|

|

| 4 | Review and evaluate the prison and jails’ policies and practices for handling the aftercare of employees who have been gassed to determine whether those policies and practices are consistent with applicable laws and regulations. | We obtained and reviewed policies and procedures regarding aftercare available to victims of gassing attacks at each of the three correctional facilities—including their processes and practices for notifying victims of their medical treatment options, psychological counseling services, and workers’ compensation benefits—to determine whether they comply with state and federal laws and regulations. |

| 5 | For the most recent three‑year period, determine how many employees sought and obtained counseling or medical treatment through their employers following a gassing incident. | For each of the 45 gassing attacks we reviewed as part of Objective 7, we determined whether the victims received medical treatment and psychological counseling. |

| 6 | Evaluate how the prison and jails ensure that employees are aware of and comply with policies and procedures related to gassing, including those related to prevention, response, and incident reporting. | We interviewed personnel and reviewed the processes that each of the correctional facilities implemented to notify and train employees regarding how to prevent and respond to gassing attacks. |

|

7

|

For a selection of gassing incidents that have occurred during the most recent three‑year period at the prison and jails, review and evaluate the following: | To address this objective, we judgmentally selected 15 gassing attacks that occurred from 2015 through 2017 at each of the correctional facilities—a total of 45 gassing attacks—and performed the following procedures at the three correctional facilities: |

|

a. Whether the prison or jails followed their respective aftercare policies and procedures following each gassing incident including whether the gassing substance was tested for disease and, if not, why. b. Whether and how soon after the incident affected employees were informed of the presence of diseases in the gassing substance. c. Whether the prison and jails investigated the incident in accordance with requirements in state law. |

|

|

| 8 | Review and evaluate the strategies that prisons and jails use to prevent or mitigate the effects of gassing incidents, including the disciplinary actions used on offenders who have attempted or committed gassings. To the extent possible, determine whether disciplinary actions are effective in deterring repeat offenders. |

To assess the correctional facilities’ strategies to prevent and mitigate gassing attacks, we reviewed the following:

|

| 9 | Identify any best practices for preventing, responding to, investigating, or providing aftercare for gassing incidents. |

|

| 10 | Review and assess any other issues that are significant to the audit. |

|

Sources: Analysis of the Audit Committee’s audit request number 2018‑106, and information and documentation identified in the table column titled Method.

We conducted this audit under the authority vested in the California State Auditor by Section 8543 et seq. of the California Government Code and according to generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives specified in the Scope and Methodology section of the report. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Respectfully submitted,

ELAINE M. HOWLE, CPA

State Auditor

Date:

September 18, 2018

Staff:

John Baier, CPA, Project Manager

Nathan Briley, JD, MPP

Ralph M. Flynn, JD

Daisy Y. Kim, PhD

Britani M. Keszler, MPA

Michaela Kretzner, MPP

Andrew Loke

Alex Maher

Itzel C. Perez, MPP

Marye Sanchez

Legal Counsel:

J. Christopher Dawson, Sr. Staff Counsel

For questions regarding the contents of this report, please contact

Margarita Fernández, Chief of Public Affairs, at 916.445.0255.