Use the links below to skip to the section you wish to view:

- 4Cs Disrupted Services to Some Families by Recording Inaccurate Information, Delaying Payments to Child‑Care Providers, and Ending Its Preschool Program

- 4Cs Made Unallowable Purchases and Failed to Meet Other Requirements of Its Contracts With Education

- 4Cs Engaged in Questionable Management of Its Retirement Plans

- Other Areas We Reviewed

- Scope and Methodology

4Cs Disrupted Services to Some Families by Recording Inaccurate Information, Delaying Payments to Child‑Care Providers, and Ending Its Preschool Program

Key Points:

- 4Cs gave unreasonable deadlines to many families for responding to its notices altering their authorized child‑care services, which resulted in its unfair termination of those services for some of those families. Specifically, 4Cs entered incorrect date information in its child‑care data system, thereby resulting in premature deadlines, including some due dates that preceded the dates that it created the notices. Because those situations automatically resulted in missed deadlines, 4Cs terminated some services, thereby creating disruptions for some of the children it was serving.

- Although neither 4Cs nor Education identified any families that claimed that 4Cs did not give them sufficient time to respond to notices, 4Cs and Education could do more to inform families of their rights to challenge actions that do not appear to be appropriate.

- 4Cs paid some child‑care providers late, which could have led to undue financial hardship for providers and families.

- 4Cs caused disruptions in some families' child care by ending its state preschool program contract.

4Cs Gave Many Families Unreasonable Deadlines for Responding to Important Notifications, Resulting in Unfair Termination of Child‑Care Services for Some of Those Families

4Cs recorded incorrect dates on more than 15 percent of its notices to families from July 2015 through June 2017, resulting in unreasonable deadlines for many of these families to maintain their eligibility for services. As state regulation requires, a contractor such as 4Cs must promptly issue notices whenever it intends to approve, deny, or make a change to its child‑care services for a family. For example, if 4Cs intends to terminate a subsidy for daycare because the family's qualifying income has become too high, 4Cs must notify the family with sufficient time—at least 14 days before the effective date of the intended action—for the family to respond. The notice must explain why 4Cs intends to terminate services and specify a notification date, which serves as the reference point for determining the amount of time the family has to address 4Cs' concern. However, we found that 4Cs staff backdated many of these notices in the child‑care data system; that is, they changed the system‑populated dates for the notices to earlier dates. These changes made it look as though 4Cs generated the notices earlier than it actually had, which let 4Cs avoid potential penalties from Education for giving inadequate notice. The earlier dates resulted in some families not having sufficient time to respond, prepare an appeal, attend a hearing about the appeal, or make alternative plans for child care. Consequently, in some instances, 4Cs terminated their child‑care services unjustly.

4Cs violated state regulation and misled many families by altering the dates on the notices. As we discuss in the Introduction, state regulation requires the 14‑day response time and provides an additional 14 days to appeal to Education if the family disagrees with the contractor's decision about its initial appeal. To address this regulation, 4Cs' procedures require its staff to prepare a notice no later than 19 days before the date it expects to change a family's service agreement. The additional five days account for delivery of the notice to the family. However, our analysis of more than 40,000 notices to families from July 2015 through June 2017 showed that 4Cs entered inaccurate dates into its child‑care data system for 6,530 notices by backdating them with notification dates that were on average about a month before they created the notices.

Because the notification date signifies the beginning of the 14‑day response period, backdating the notification date shortens the response period. For example, 4Cs created one notice on December 1, 2015, with a notification date of November 14, 2015, in its data system. Allowing for the five‑day delivery period, the due date for the family to respond should have been December 20, 2015—19 days later. However, because 4Cs used November 14 as the notification date, it established the due date for the family to respond as December 3, only two days after 4Cs created the notice. This gave that family no realistic chance to meet the deadline, and 4Cs terminated child‑care services for two children in the family immediately on December 4. For another family file we reviewed, 4Cs created the notice on March 7, 2017, with a notification date of February 1, 2017 in its data system. In this case, the due date for the family to respond should have been March 26, 2017—19 days later. However, because 4Cs used February 1 as the notification date, February 20 was the date for the family to respond, more than two weeks before 4Cs had even created the notice. 4Cs did not give the family any opportunity to respond, and it discontinued services for two children in that family as well.

In our review of the 6,530 backdated notices from July 2015 through June 2017, we identified 1,220 that 4Cs issued to families announcing that their services could be terminated. As illustrated in Figure 2, 4Cs created 1,141 of these notices with 18 or fewer days for a response instead of 19 days. In particular, 407 of these notices carried appeal dates that preceded the dates the notices were actually created, thereby making it impossible for families to respond within the required time frame to retain their child care. 4Cs also created 124 notices within five days of the appeal date, making it unlikely that the families had sufficient time to appeal the notice. Further, 4Cs created 271 of these notices between 6 and 13 days before the appeal date, fewer than the 14 days established in state regulations. We reviewed the case files for 10 of these backdated notices of potential termination of services and determined that some families did not ultimately lose services, such as a family that the 4Cs case manager was eventually able to contact after the appeal date. However, we found that in four of the 10 cases, families subsequently lost child‑care services, leading us to conclude that some of the other backdated notices also resulted in lost services. In summary, the practice of backdating causes hardships to many families.

Figure 2

4Cs Backdated Termination Notices in Fiscal Years 2015–16 and 2016–17

Source: California State Auditor's analysis of 4Cs' child‑care data.

Note: 4Cs backdated an additional 10 termination notices that did not include an appeal date.

We identified the incorrect dates by comparing the date 4Cs staff recorded on the notice to the date recorded in the child‑care data system. When a notice is created in the data system, the notification date is automatically populated with that day's date. However, this date can be edited by 4Cs staff. Thus, 4Cs staff would have to specifically alter the notification date for the notice to be backdated. The child‑care data system also records the date the notice was entered into the data system, and this date can be viewed but not altered by the user. We requested that 4Cs explain why its staff backdated notices, but 4Cs did not provide any rationale for its actions, nor did it provide any information about circumstances in which its staff would be justified in altering the notification date.

Education's oversight of 4Cs, in particular its contract monitoring reviews, has not been able to detect 4Cs' practice of backdating its notices or to identify the bad effect that this activity was having on families. If Education were to find evidence of backdating, state regulation allows it to enforce consequences for violating the terms of its contracts, up to and including terminating those contracts. However, staff in Education's Early Education and Support Division acknowledged that Education would have difficulty detecting the backdated notices through its current program monitoring reviews because it only reviews hard copy notices and does not examine the data in the child‑care data systems its contractors use. Staff also characterized Education's review as focusing on whether its contractors send notices in a timely manner. Although we did not analyze 4Cs' timeliness in processing these notices, we believe that the practice of backdating could conceal a contractor's chronic lateness. For example, a contractor could address a backlog of notices not yet entered in its computer system by backdating them to make it appear that it had processed them on time, thereby avoiding possible sanctions from Education. The program manager of 4Cs' subsidy department acknowledged that 4Cs staff had previously engaged in backdating under its former leadership, but asserted that under his leadership, this practice will no longer occur.

4Cs and Education Did Not Provide Sufficient Information to Families About the Process for Appealing 4Cs' Actions

Because of the large number of backdated notices that may have affected families' child‑care services, we expected to find numerous instances of families filing appeals. However, we did not identify any such instances. 4Cs' director of compliance told us that in fiscal year 2016–17, 4Cs did not receive any appeals related to unreasonable deadlines, although she was unable to ascertain whether any such appeals had been received in prior years because 4Cs' records are incomplete for those years. Similarly, the appeals unit manager at Education's Early Education and Support Division reported that Education did not receive any appeals about unreasonable deadlines from fiscal years 2015–16 through 2016–17. However, we identified two key factors that may have contributed to the lack of appeals: 4Cs did not provide sufficient information to families about the requirements and expectations for filing appeals with it or with Education, and 4Cs provided limited information to parents about how to contact Education with questions or concerns.

As noted previously, when a family receives a notice about a potential reduction or change in its service agreement, it has 14 days to respond to 4Cs if it disagrees with the agency's rationale for the proposed revision. 4Cs uses its parent and provider handbook and the notices to provide information to families about the appeal process, and these documents contain important information such as the 14‑day response period for families to file appeals. However, neither the handbook nor the notice describe valid grounds for a family to file an appeal. In addition, the handbook identifies only a mailing address for contacting Education, and although some of the notices we reviewed included a telephone number, others identified only a mailing address and a fax number for Education. Providing additional forms of communication such as an email address or a link to Education's website that families can use to ask questions, would facilitate prompt responses to inquiries about the appeal process and clarification of the grounds for filing successful appeals.

Education has not established any procedural requirements for its child development contractors to share specific information with their clients about the process for appealing notices of planned service changes. Specifically, Education requires its contractors to follow state regulation, which states only that contractors such as 4Cs are to provide information to parents on appeal process procedures but does not specify the format or level of detail needed. Although Education informed us that it requires its contractors to follow this regulation, our review determined that families are not using the appeal process to address concerns about insufficient time to respond to notices of service changes, which we believe may be because of the lack of specific information about the process. If Education required its contractors to provide more complete information to families about the appeal process, families might find the process more understandable and accessible.

Another factor pertaining to the absence of appeals is 4Cs' lack of guidance to its staff about how to inform families of their rights. 4Cs' policies do not require staff to explain to families when and how they can file an appeal or their right to the 14‑day response period. It is important for families to know when to question the appropriateness of 4Cs' actions—such as whether 4Cs provided sufficient time to respond to notices—and how to challenge any potential disruptions to services.

4Cs Paid Its Child‑Care Providers Late in Some Instances, Which May Have Led to Undue Financial Hardship

In accordance with state regulations, 4Cs maintains policies governing its provider reimbursement processes that are intended to ensure prompt and consistent reimbursement for services. As we describe in the Introduction, providers submit monthly attendance sheets to 4Cs identifying the services they performed and for which they seek reimbursement. These attendance sheets are due by the 5th day of the month following the attendance period. 4Cs' policy is to send reimbursement checks on the 15th day of the month for those attendance sheets it receives by the 5th. For providers who miss that deadline, the policies state that 4Cs will send checks on the last business day of the month to providers for attendance sheets received between the 6th and the 20th day of the month. Any attendance sheets submitted after that period will be processed for payment with attendance sheets for subsequent months.

4Cs did not always follow its policy to promptly pay providers, as evidenced by five late provider payments we identified among the 60 we reviewed from fiscal years 2014–15 through 2016–17. In these instances, 4Cs received the timesheets from providers on or before the 5th day of the month, but mailed the reimbursement checks on the last business day of the month, resulting in late payments ranging from 13 to 16 days. Two payments were for more than $2,000 each. In total, we identified $7,905 in late payments.

For four of the late payments, the accounting supervisor in 4Cs' fiscal department explained that she could not issue the payments on time because of delays in receiving required information from 4Cs' subsidy department. For example, one payment was mailed late because a case manager from the subsidy department who created the child‑care service certificate did not forward it to the fiscal department until after the 5th of the month. The child‑care service certificate allows 4Cs to verify whether the care provided is consistent with the type and amount authorized. 4Cs' accounting supervisor was not able to determine why the other payment was late. She indicated that communication between case managers and the fiscal department can be inconsistent and that while 4Cs currently has informal practices addressing communication between the fiscal and subsidy departments, 4Cs could improve these practices.

When 4Cs does not pay child‑care providers promptly, it may create hardship for the providers and could jeopardize the continuous delivery of child‑care services for families in need. Because 4Cs' families require child‑care services to maintain employment or attend classes, the loss of those services could result in them having to find more expensive child care or reduce their work hours.

4Cs Appears to Have Ended Its Preschool Contract in an Unsuccessful Attempt to Avoid Additional Scrutiny From Education

In March 2017, 4Cs informed Education of its intent to terminate its California State Preschool Program (CSPP) contract, just two days before Education's April 1 annual deadline for deciding whether to renew 4Cs' contracts. Although state regulations and contract provisions allowed 4Cs to cancel its contract at any time, this decision resulted in the closure of 4Cs' preschool facilities in June 2017, and forced some families to transition their child‑care services elsewhere on short notice. In one example we found, the family appeared to receive notification from 4Cs only one month before the preschool closed. This decision undermined the continuity of care and education for the children the program had been serving.

According to Education, it had decided to place 4Cs' CSPP contract on conditional status as a result of health and safety concerns at preschool sites. State law provides for Education to designate a contract with a child‑care agency as conditional when there is evidence of fiscal or programmatic noncompliance with the agency's operations. A contract Education places under conditional status is subject to any restrictions deemed reasonable by Education to ensure compliance, and if the contracting agency fails to demonstrate substantive progress toward its compliance goals within six months, Education may terminate the contract for any applicable cause. State law stipulates that when an agency has one contract designated as conditional, all of the agency's other child‑care and development contracts are also deemed to be under conditional status.

To obtain perspective on the rationale for 4Cs' actions, we interviewed 4Cs leadership. Its chief financial officer stated that high costs for temporary employees resulting from the difficulty in hiring permanent preschool teachers was one of the factors in relinquishing the contract, although 4Cs could not provide any type of analysis to substantiate that claim. We also interviewed 4Cs' former executive director, who was leading the organization at that time. He provided a copy of an email he sent in March 2017 to an administrator at Education. In that email, he stated that he believed Education had recommended that 4Cs relinquish its CSPP contract, and he also indicated that 4Cs would do so to protect its other contracts from being placed on conditional status. However, even though 4Cs terminated its CSPP contract, Education's Early Education and Support Division requested that Education's audits division conduct a performance audit of 4Cs' six other contracts based on concerns about 4Cs' management of its contracts and, in particular, its closure of preschool centers. Education expects to complete this audit, which it considers a form of additional scrutiny, in September 2018. We discuss the audit in further detail later in this report.

Recommendations

4Cs

To ensure that families have sufficient time to respond to notices regarding eligibility, 4Cs should establish specific controls in its child‑care data system by July 2018 to prevent staff from backdating the notification dates of notices, and it should begin conducting periodic reviews of notification dates in the data system by October 2018 to ensure that the controls are effective.

To ensure that families understand how to elevate appeals to Education, 4Cs should amend its notice forms and its handbook by October 2018 to consistently describe additional means for contacting Education beyond a mailing address and fax number, such as a telephone number, an email address, and a link to Education's website for online information about reporting appeals.

To ensure that it is processing all provider payments promptly, 4Cs should formalize policies by October 2018 that address communication between its subsidy department and fiscal department regarding provider payments. These policies should be clearly communicated to both departments and provide a way for staff to be held accountable for late communications resulting in delayed payments to providers.

Education

To make its appeal process more accessible to families who may not receive a satisfactory resolution from its contractors, Education should, by October 2018, require that its contractors share key information in their communications with families about the process for appealing notices. The required information should include valid grounds for a family to file an appeal as well as information or documentation Education would need in order to review the family's appeal of adverse decisions regarding their child‑care services. Education should also require contractors to incorporate this information into contractually mandated staff training and into publicly available policies and procedures.

4Cs Made Unallowable Purchases and Failed to Meet Other Requirements of Its Contracts With Education

Key Points

- 4Cs used state funds for unallowable purposes in numerous instances. It sought reimbursement from Education for many questionable costs, including certain legal expenses, food, and personal amenities.

- 4Cs did not retain sufficient documentation for most of the transactions we reviewed to demonstrate that it had followed its own purchasing procedures. The absence of such documents raises concerns about whether 4Cs made these purchases in accordance with contract provisions and state requirements.

- 4Cs did not comply with the terms of its child‑care contracts with Education in three key areas: determination of eligibility and need, staff development, and program self‑evaluation.

- Education did not detect some of the types of contract noncompliance we identified at 4Cs, which demonstrates a need for Education to more closely monitor its contractors. In addition, Education did not adequately document its reviews.

4Cs Used State Grant Funds for Unallowable and Questionable Purposes, Including Paying for Certain Legal Expenses, Food for Its Board Members, and Personal Amenities for Staff

State regulations and Education's Funding Terms and Conditions (contract terms) stipulate the types of costs for its child development contracts that are reimbursable and those that are not. Further, state law and the contract terms require that contractors be audited pertaining to their use of state funding. As described in the Introduction, Education requires annual independent financial and compliance audits of its contractors, which must conform with the uniform cost principles, federal regulations that describe allowable uses of grant funds.

In our review of expenditures for which 4Cs requested reimbursement, we primarily selected administrative costs that appeared less typical of child development contracts than larger and more common expenditures, such as salaries, benefits, and payroll taxes. State regulations require contractors to request reimbursement by submitting their attendance and financial reports periodically in accordance with the annual contract. With respect to administrative expenses, Education requires its contractors to report those costs in aggregate as a single line item, thereby precluding it from evaluating specific transactions when reimbursing its contractors. However, Education does require the contractors to maintain sufficient documentation to support the validity and appropriateness of these expenditures. Although Education does not require contractors to submit documentation with their financial reports to support the expenditures, those expenditures are subject to review as part of the contractors' required annual independent audits. As we discuss later in this report, Education relies on these audits to determine the appropriateness of a contractor's expenditures.

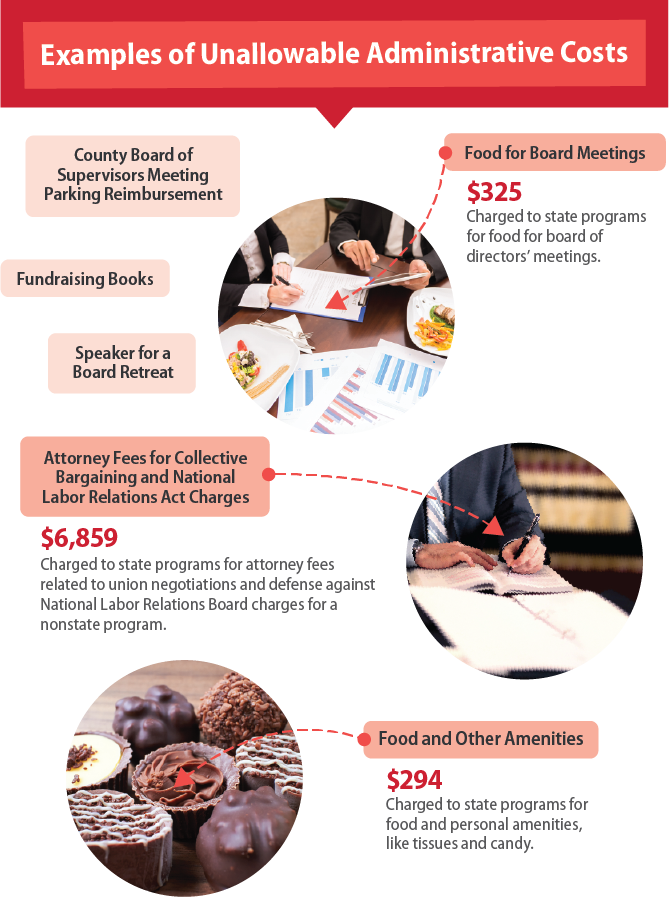

We reviewed 69 administrative costs pertaining to travel, conferences, supplies, and professional services that 4Cs incurred from July 2014 through June 2017. We determined that 22 of the 69 were not allowable for reimbursement per state and federal regulations and the contract terms. These expenditures totaled $11,217 in state funds. Figure 3 provides an overview of the types of unallowable costs we identified.

First, 4Cs claimed reimbursement for legal services in labor union negotiations and in defending the organization from charges filed with the National Labor Relations Board that it violated the National Labor Relations Act in relation to a private program. One of the transactions we reviewed included one invoice related to legal services for defending against those charges and another invoice for collective bargaining, both of which resulted in 4Cs spending a total of $6,859 of state grant funds. According to state regulation, Education will reimburse contractors for actual costs that are reasonable and necessary to the performance of the contract. However, the legal services for both invoices pertained to 4Cs' operation of a private preschool, Orchard Early Learning Center, whose activities are unrelated to the administration of state child care and development contracts. In particular, funds for these state contracts cannot be used to support private child‑care centers. According to 4Cs' accounting manager, 4Cs transformed the private preschool into a state program. However, 4Cs did not provide any documentation to substantiate this assertion, so we conclude that this cost is unallowable.

Second, for five transactions we reviewed, 4Cs used state grant funds to purchase food for board meetings, which is an unallowable use of state funds. According to state regulations and the contract terms, compensation to board members, including payment for meals unrelated to authorized per diem travel expenses, should not be reimbursed by the State. Although state regulations allow for state funds to pay for meal expenses incurred as a result of business travel away from headquarters to conduct state business, they specify that business meals are not reimbursable when agencies hold meetings with their own employees to conduct state business. These five transactions were for food purchased from restaurants specifically for 4Cs' board meetings, with state funds paying a total of $325 of those purchases. 4Cs' accounting manager said he believes that having food at the board meetings helped facilitate those meetings, which addressed strategic and operational initiatives of 4Cs. He also shared 4Cs' belief that the food is not compensation to members of its board. However, as previously described, state regulations specify that food purchases for board members unrelated to authorized per diem travel expenses are not reimbursable from state child development contract funds.

Figure 3

4Cs Spent State Funds on Unallowable Administrative Costs

Sources: California Code of Regulations, title 5, sections 18033, 18034, 18035, and 18067; 2 Code of Federal Regulations part 200; California Department of Education's Funding Terms and Conditions; and California State Auditor's analysis of 69 administrative costs 4Cs incurred between July 2014 and June 2017.

4Cs claimed reimbursement from state grant funds for personal amenities, which is in direct violation of the uniform cost principles. Although these principles specify that contractors may not be reimbursed for goods and services for personal use, we found that 4Cs claimed reimbursement for four transactions of this nature. The expenditures, some for multiple items, were for hand sanitizer, water, a floor heater, tea, tissues, and candy, with state funds paying $294 of those purchases. Although these items may seem minor, we question whether 4Cs made other additional purchases of goods and services for personal use with state funds, since we reviewed less than 1 percent of its administrative costs claimed for reimbursement from fiscal years 2014–15 through 2016–17. As we did with the other unallowable costs referenced earlier, we requested on multiple occasions that 4Cs provide justification for using state funds to pay for personal amenities, but it did not provide any such documentation.

In addition, we noted nine transactions for which 4Cs did not maintain sufficient documentation to enable us to determine whether specific costs were allowable for state reimbursement. For example, one transaction was for recruitment advertising, but there was no supporting documentation to describe the nature of the transaction, leading us to question whether it was allowable under the uniform cost principles. Given the concerns we previously identified with the allowable nature of certain expenditures, the large number of transactions with insufficient documentation raises concerns about whether 4Cs may be using state funds for other purchases that are not reasonable and necessary for carrying out its contractual obligations.

4Cs Lacked Sufficient Documentation to Justify the Reasonableness of Other Administrative Expenses It Paid Using State Funds

State regulation and the contract terms require that contractors maintain documentation supporting their claims for reimbursement. However, most of the 69 administrative costs we reviewed did not contain sufficient documentation to demonstrate that 4Cs used state grant funding appropriately, as shown in Figure 4. Without sufficient documentation, such as invoices, purchase requisition and receiving forms, receipts, and disbursement approval forms, 4Cs cannot demonstrate that such administrative costs are reasonable and necessary for the administration of its contracts with the State and that its costs are allowable per state law, the contract terms, and the uniform cost principles.

Of the 69 transactions, 56, or 81 percent, were missing at least one key document or contained a discrepancy in the documentation. For instance, we identified eight purchases for which 4Cs could not provide the supporting receipts, such as one transaction for lunch for a training that was missing a receipt and employee expense reimbursement form. Without either form of documentation describing the purpose of the purchase, it is unclear whether this cost pertained to a legitimate business need.

Figure 4

4Cs Did Not Maintain Supporting Documentation During All Four Stages of Its Purchasing Process

Sources: California State Auditor's analysis of 69 administrative costs incurred by 4Cs from July 2014 through June 2017, 4Cs' purchasing documentation, and 4Cs' accounting policies manual.

Note: Not all purchases required all of the supporting documentation mentioned above.

4Cs also did not comply with the purchasing approval requirements in its own accounting policies and procedures. Its accounting policies manual requires authorized purchasers to sign a disbursement approval form for each purchase of goods and services and requires its management staff to approve the purchase by also signing the form. However, 4Cs' documentation for 40 of the 62 purchases that should include such a form, did not. As an example, one of these purchases was for books on effective techniques for fundraising, but the lack of a disbursement approval form raises concerns about whether 4Cs exerted any management review over this and other expenditures and whether the organization made unnecessary or inappropriate state‑funded purchases. We requested on multiple occasions that 4Cs provide its justification for this missing documentation, but again it did not do so.

Education Uses Annual Independent Audits to Monitor Its Reimbursements of 4Cs' Administrative Costs

As previously mentioned, Education relies on annual independent audits to oversee the use of state funding for its child development contractors. State law requires Education's contractors to obtain annual independent financial and compliance audits, and it requires Education to rely on the audit if it meets generally accepted auditing standards. These audits can identify unallowable or questionable costs pertaining to the contractors' use of state funds, although the independent audits obtained by 4Cs for fiscal years 2014–15, 2015–16, and 2016–17 did not identify any such costs.

We believe that reliance on these audits is insufficient to detect certain potential misuses of state funds. 4Cs' independent auditor informed us that it sampled administrative costs using a nonstatistical method of auditor judgment that usually results in larger amounts being selected. In contrast, our review focused on cost categories such as travel, conferences, supplies, and professional services—categories that by nature have a higher likelihood of including costs that may appear questionable. Without any additional monitoring beyond the annual independent audit, Education is unlikely to identify misuses of state funds pertaining to these types of transactions.

Education—through its audits division—is required by law to rely on the independent audits to evaluate the financial activities of its contracts, and any additional work should build upon the work already performed. The director of the audits division informed us that her division performs reviews of the independent audits using a standardized report checklist as a resource, which includes a section addressing administrative costs. Education's procedures focus primarily on verifying whether the administrative costs claimed on the contractor's attendance and financial reports reconcile to the schedule of administrative costs in the independent audit report and determining whether administrative costs claimed are within the limit of 15 percent of net reimbursable costs allowed by its contracts.

According to the director of the audits division, the division conducts additional performance audits of high‑risk contractors based on requests received from the Early Education and Support Division and on the results of risk assessments it performs when resources are available. The audits division is currently conducting a performance audit of 4Cs that it started in March 2017, from a request by the Early Education and Support Division as we noted earlier, and it anticipates completing the audit in September 2018.

The scope of Education's audit is to determine whether 4Cs properly administered its child care and development program funds for the period from July 2015 through September 2016 in accordance with program requirements and each of 4Cs' Education contract Funding Terms and Conditions. The director stated that the specific performance audit areas include internal controls, eligibility, general expenditures, payroll expenditures, cost allocation, and other transactions, and that administrative costs are incorporated as part of the expenditure testing. The director also stated that the audits division has not performed any recent risk assessments because it has not had excess audit resources for an extended period, and it does not anticipate having any additional resources available for at least the next year.

4Cs Insufficiently Administered Portions of Its Child‑Care Contracts, Leading to Errors in Family Files and Undermining Its Ability to Provide Comprehensive, Coordinated, and Cost‑Effective Child‑Care and Child Development Services

As noted in the Introduction, 4Cs contracted with Education for fiscal year 2016–17 to administer seven child‑care programs on behalf of the State. We identified specific weaknesses in how 4Cs administered the contracts for these programs, thus jeopardizing the effective and efficient delivery of its child‑care services. We used Education's monitoring guide—described in the Introduction—to determine that 4Cs' practices were insufficient in three areas: determination of eligibility and need, staff development, and program self‑evaluation. We specifically focused on these contract areas in order to assess the overall quality of 4Cs' program administration, to evaluate 4Cs staff's consistency in interacting with families, and to assess fairness and quality in its development of staff.

4Cs did not consistently maintain documentation to substantiate the eligibility and need of applicants for subsidized child‑care services. State regulation and nearly all of Education's contracts require 4Cs to assess the eligibility and need of families applying for services by documenting specific information, such as income and family size, in a family case file. However, 11 of the 24 family case files we reviewed contained deficiencies in the support 4Cs used to determine eligibility for services. For instance, six family case files did not have sufficient support to substantiate the need for services. State regulation requires families to document this need based on employment, seeking of employment, training, or other criteria for 4Cs to determine accurately the amount of the benefit the families should receive. Without adequate documentation, 4Cs cannot justify the amount of benefits it provides to families.

When we asked 4Cs for its formal policies for determining need and eligibility, it referred us to its parent and provider handbook, which its staff use as a policy guide for making these determinations. However, this handbook is designed for use by parents and providers rather than by 4Cs staff. For example, the handbook does not contain specific procedures 4Cs staff would perform to determine the particular eligibility of a family. In particular, the handbook does not specify that case managers must use an income calculation worksheet to determine a family's income. 4Cs also provided us with examples of training materials it prepared that described some of these steps that it directed its staff to use. However, we believe that its staff would better document their eligibility determinations if 4Cs were to formalize its operational procedures.

Education's child‑care grant contracts require contractors, such as 4Cs, to implement a staff development program. However, we identified substandard components in 4Cs' program, which may have contributed to the deficiencies mentioned earlier in determining families' need and eligibility. 4Cs' contracts with Education require it to identify staff training needs and establish orientation plans for new staff, but for most of its child‑care programs, 4Cs could not provide sufficient evidence that it met these contract requirements.

Based on our review of 4Cs' training materials, we determined that it had not established an orientation plan for six of its seven programs. For these six programs, 4Cs could not provide evidence of having prepared a plan, such as a schedule or listing of information new program staff may find helpful, including the program's role within 4Cs and general administrative procedures. Additionally, 4Cs did not identify the training needs of its staff. Although we found that 4Cs had taken some steps to plan staff training for one program—its Resource and Referral program—it could not provide evidence that it strategically identified its staff's training needs and directed staff members to attend training relevant to these identified needs. By not identifying and documenting the program‑specific training needs of its staff, 4Cs' management cannot determine whether it has provided staff with the necessary information to perform their work effectively. For example, the Early Education and Support Division published 19 management bulletins in 2017 pertaining to child development contractors that added requirements to 4Cs' work in addition to the many regulations that already governed 4Cs' fiscal year 2016–17 contracts with Education. The complexity of laws and regulations that govern child‑care programs makes it challenging for 4Cs to keep staff up to date if it does not maintain a thorough staff development plan. 4Cs could use such a plan to develop training for informing staff of any significant changes in policies and procedures to facilitate the efficient delivery of services. Similarly, participating in new staff orientations is important for employees to understand their roles and responsibilities within the organization.

4Cs also did not follow all of the required self‑evaluation process as stipulated in its contracts with Education. Education requires its contractors to engage in an annual self‑evaluation process for each contract, whereby the contractor evaluates the quality of its programs using prescribed criteria from Education. That process requires 4Cs to document and incorporate feedback from key stakeholder groups: its staff, members of its board, and—for four of the programs it operates—the families receiving services. In our analysis of 4Cs' fiscal year 2016–17 program self‑evaluation document, we found insufficient evidence that 4Cs used staff or board member feedback to assess any of its child‑care programs.

Further, although we found that 4Cs surveyed many parents, it did not demonstrate that it used feedback from parents in its self‑evaluation for three of the four programs for which it was required to do so. With respect to program assessments from board members, 4Cs could not provide documentation of these assessments, casting doubt on whether it incorporated sufficient feedback from its board. Although we found evidence that 4Cs staff informed its board of directors about the self‑evaluation process, its documentation of board activities does not reference program assessments from any board members. Consequently, 4Cs may have missed an opportunity to have its board members identify program strengths and weaknesses and set a direction for the programs that will be sustainable and align with the organization's goals. Without analyzing and collecting feedback from staff, parents, and its board, 4Cs hinders its ability to improve in ways that are meaningful to its stakeholders.

In addition to concerns about the lack of feedback, we found that 4Cs' self‑evaluation process addressed its contracts broadly, rather than incorporating specific observations unique to each contract as 4Cs' contracts with Education require. 4Cs incorporated some stakeholder comments via family surveys for its Resource and Referral program contract and, throughout its self‑evaluation documents, 4Cs occasionally provides information about its specific programs. However, 4Cs uses a single set of program self‑evaluation documents that does not address each of its contracts individually. For instance, its documents include a standard section on plans for parent involvement, which is specifically required in three of its contracts. Because of the differences in services among these contracts, each program uses a different approach for parent involvement. One contract provides for parent education relevant to the children's transition from preschool to kindergarten, another contract provides for career training for parents, and the third requires educational training for parents whose children receive care in providers' homes rather than in a formal preschool setting. Because of these different approaches to parent involvement, we expected that each program would have its own parent involvement plan. However, the section in the self‑evaluation document covering parent involvement briefly discussed only two of the three programs, and its summary does not differentiate between the parent involvement each program carries out. Because it has not created evaluation information specific to each program, 4Cs lacks any significant ability through its self‑evaluation process to identify the needs of each program and make targeted improvements.

Each of 4Cs' contracts with Education requires it to have procedures for recurring monitoring to ensure that satisfactory areas of the program continue to meet standards and that the contractor promptly and effectively addresses areas needing modification. Just as 4Cs does not identify each individual program's strengths and weaknesses, it also does not monitor individual programs' areas of effectiveness and could not provide documentation of procedures for doing so. Failure to conduct such monitoring limits 4Cs' ability to track its performance over time; thus, 4Cs cannot ensure its effectiveness in meeting the needs of the clients it is serving.

Education's Mandated Contract Monitoring Did Not Detect Certain Types of Noncompliance We Found at 4Cs

Using Education's monitoring guide, the only documented resource that specifies the criteria to use when conducting a review of contract requirements, we concluded that 4Cs was noncompliant with specific requirements of its contracts with Education, and 4Cs' management agreed. However, when we shared our observations with Education, its Early Education and Support Division's management informed us that it had conducted a contract monitoring review in December 2017 and determined that 4Cs was compliant in two of the three areas of concern to us. Although Education also found errors in 4Cs' determination of eligibility, it concluded that 4Cs had complied with its contract requirements for establishing a staff development program and for conducting a program self‑evaluation process. According to the Early Education and Support Division's management, it used both the monitoring guide and its reviewer's overall knowledge of 4Cs' practices to reach its determination. For example, it used its reviewer's observations of 4Cs staff attending Education's training sessions as partial support for 4Cs' identification of staff training needs. However, because Education does not document the process its reviewers use, it cannot sufficiently support its conclusion that 4Cs is complying with contract requirements.

The contract requirement that 4Cs identify its staff's training needs is another example of how Education's analysis differed from our conclusions. In this instance, the Early Education and Support Division made its determination using the monitoring guide along with other sources. One source was an internal 4Cs staff survey that asked staff members about their wishes and needs for training, and another source was a series of conversations with 4Cs management about orientation plans. Yet the monitoring guide does not identify staff input, such as this survey, as an item to review when assessing a contractor's staff development program, and 4Cs did not provide this survey to us when we conducted our review.

Because Education did not document the elements it reviewed when performing its contract monitoring reviews, we had no way of knowing about other items it considered in its assessment. Moreover, without this documentation, Education cannot demonstrate how it determined 4Cs' compliance when questions arise about whether 4Cs is meeting its contractual obligations.

We also found that Education interprets a program self‑evaluation contractual requirement differently from how its contracts describe it—a reason that one of its conclusions differs from ours. We concluded that 4Cs was noncompliant in its obligation to use feedback from key stakeholders in its program self‑evaluation process, while Education determined that 4Cs sufficiently fulfilled that requirement. Specifically, state regulations and 4Cs' contracts stipulate that 4Cs must include a program assessment by its board members in its annual program self‑evaluation plan. We expected that this assessment would involve board members actively identifying program strengths and weaknesses and suggesting approaches for the organization to take action. Although we found evidence that 4Cs staff informed its board of directors about the self‑evaluation process, 4Cs could not provide documentation that board members assessed any of its programs or that it incorporated any such assessments in its plan.

Even though its contracts require 4Cs to include an assessment of its programs by the agency's board, Education's Early Education and Support Division's management informed us that it believed an assessment by the board was not necessary, and 4Cs needed only to inform its board about program performance. Further, the Early Education and Support Division considered documentation in 4Cs' board minutes referencing the board's awareness of the status of 4Cs' contracts as sufficient evidence that 4Cs had met this requirement. However, the minutes do not demonstrate that the board conducted an assessment, as the contracts require.

As mentioned previously, Education does not require its staff to document their rationale for concluding that a contractor has complied with a contract requirement. Education's current practice is to retain documentation to justify its findings only in instances of noncompliance. In situations where Education finds a contractor to be in compliance with its contracts, its staff do not document the evidence they used to make those determinations.

Yet without documentation of compliance, Education could not support its conclusions that 4Cs was in compliance in areas where we found noncompliance. The absence of documentation of those efforts also inhibits Education's ability to ensure that its own staff perform consistent and thorough reviews when monitoring 4Cs and other contractors. Because Education's staff already obtain and assess documentation as part of their review, they could simply describe those items on a checklist used to support their conclusions. In cases where key evidence came from observations or interviews by Education staff, these staff could describe that evidence on the same checklist.

Our July 2017 audit report, California Department of Education: It Has Not Ensured That School Food Authorities Comply with the Federal Buy American Requirement, Report 2016‑139, similarly found that Education failed to retain evidence of contract compliance monitoring. In that audit, the failure inhibited Education's ability to monitor whether school districts purchased appropriate types of food for students in accordance with federal law. Education informed us following that audit that it would not implement our recommendation that it should retain that evidence. As we stated in that report, without the ability to review its staff's work, Education's management cannot ensure that its staff accurately or consistently review its contracting agencies.

In the case of 4Cs, because staff do not document the evidence they use to reach their assessments that contractors comply with contract requirements, Education's management cannot justify those evaluations when clients or the public raise concerns about a contractor's performance. If Education implemented policies and procedures to document the evidence it uses for its conclusions, this approach could benefit its monitoring efforts elsewhere. For instance, Education staff could use examples of contracting agencies that have complied with particular requirements to identify patterns of success, which it could then share with its other contractors. These examples could strengthen Education's training and technical support to its contractors by identifying best practices to disseminate statewide and by formulating effective training for its staff who monitor these contractors.

Education reports comparative data for error rates found among its contractors. As described in the Introduction, error rates are Education's measure of administrative performance. In the Budget Act of 2014, the Legislature required Education to review and compare a sample of its contractors and report on their performance for fiscal year 2014–15. Education included 4Cs and some of its other contractors in this review and detected error rates based on four categories: eligibility, need, family fee, and provider reimbursement. As part of its report to the Governor and the Legislature titled Administrative Errors in Alternative Payment, CalWORKS, and General Child Care Programs for Fiscal Year 2014–15, Education reported an error rate of 2 percent for 4Cs for fiscal year 2014–15, placing it among the better half of performers for that year. Education reviewed 4Cs' error rate again in December 2017, but as of March 2018, it has not issued its final report.

Recommendations

4Cs

To ensure that it can justify the costs for which it seeks reimbursement, 4Cs should, by October 2018, strengthen its controls over its approval of the expenditures it charges to the State's share of its funding. These controls should include retention of all documentation to justify appropriate approval of these expenditures.

To ensure that the amount of benefits it provides to families is justifiable, 4Cs should develop formal procedures by October 2018 for its eligibility determinations, including a policy to retain in the family case files the documentation it uses to determine eligibility.

To ensure that staff possess the required knowledge and skills to assist families with child‑care programs, 4Cs should develop and implement procedures by October 2018 to identify staff training needs and create orientation and training plans to meet those needs.

To ensure effective child‑care programs, 4Cs should document separate self‑evaluation and monitoring procedures for each child‑care program when it prepares its future self‑evaluation documents. Each of these self‑evaluation processes should demonstrate how it used stakeholder feedback to improve each program and monitor each program's effectiveness.

Education

In order to rectify 4Cs' inappropriate use of state funding, Education should, by October 2018, recalculate the amount of 4Cs' reimbursable costs based on the unallowable costs we identified and recover any funds that should be repaid.

After completing its performance audit in September 2018, Education should determine whether to conduct any follow‑up reviews of 4Cs' administrative costs and whether it needs to expand its procedures for identifying questionable costs. In addition, Education should determine whether the results of its audit identify any systemic issues pertaining to administrative costs for which it should consider expanding its audit procedures over administrative costs claimed by its other child‑care contractors.

To ensure that its contractors can effectively make program improvements and maintain successes in ways that are meaningful to their stakeholders, Education should adopt measures to ensure its contractors follow the terms of their contracts by demonstrating that their board members conduct a critical appraisal of each education program.

To strengthen the quality of its monitoring efforts, Education should create and implement procedures by October 2018 for staff to document the evidence used to support their contract monitoring reviews. Further, Education should use the results and evidence of compliance identified in these reviews to enhance its comparative performance measures and formulate effective training for its contractors.

4Cs Engaged in Questionable Management of Its Retirement Plans

Key Points

- Its former executive director committed 4Cs to follow the recommendations of its financial adviser, who subsequently received substantial financial commissions.

- 4Cs could not demonstrate that it met applicable reporting requirements for its primary retirement plan.

- 4Cs engaged in questionable practices in administering its state‑funded supplemental retirement plan.

Late in our audit process, we discovered that a group of current and former employees of 4Cs had filed a class action lawsuit in federal court alleging that 4Cs violated federal and state law in administering its retirement plans. In order to avoid interfering with pending legal proceedings, we do not reach any legal conclusions on those matters that are the subject of the litigation.

Its Former Executive Director Committed 4Cs to Follow the Recommendations of Its Financial Adviser, Who Subsequently Received Substantial Financial Commissions

In 1987 4Cs established a defined contribution retirement plan (primary plan) for its employees. The terms of the primary plan specify that 4Cs is to contribute a monthly amount, defined by a percentage of the employee's current salary, into a retirement account for each eligible employee. According to 4Cs, its board is responsible for establishing the contribution percentage and has the authority to revise that percentage each year. The plan does not require employee contributions, but does allow employees to roll over retirement funds from another qualified plan or individual retirement account (IRA). To be eligible to participate in the primary plan, an employee must be at least 18 and have completed one year of employment at 4Cs. The plan's vesting schedule entitles employees to 50 percent of these contributions after three years of employment, 75 percent after four years, and 100 percent after five years.

Federal law, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), governs the establishment and operation of employer‑maintained retirement plans, including minimum standards relating to participation, vesting, funding, disclosure, and reporting. ERISA requires employer‑sponsored plans, such as 4Cs' primary plan, to be in writing and to provide for one or more fiduciaries to control and manage its operation and administration. ERISA defines a fiduciary as any person who exercises authority or control over the management of a retirement plan. Fiduciaries are required to perform their duties in the best interest of participants and beneficiaries and for the exclusive purpose of providing benefits to them; they are also responsible for defraying reasonable administrative costs of administering the plan. ERISA requires that fiduciaries not engage in transactions between the retirement plan and a party in interest, such as a financial adviser, where there is a monetary incentive or other type of benefit to the party in interest.

Based on our review of retirement plan records that 4Cs had in its possession, we determined that the former executive director followed the advice of a financial adviser and used funds from the primary plan to purchase securities containing restrictive provisions. Those provisions impose substantial charges for liquidating the securities within 15 years of a participant's enrollment in the primary plan. In addition, the financial adviser received commissions from the company that held those securities.

We were unable to obtain any information about how 4Cs first established its relationship with this financial adviser because 4Cs does not have documentation about the origins of the relationship. Potential sources of the financial adviser's commissions may be from investment earnings from the securities as 4Cs enrolls new participants in the primary plan and from withdrawal charges as retirees receive distributions from the funds in their accounts. Because of the absence of documentation, we cannot conclude with certainty the amounts or frequency of the commissions and what portion of the commissions come from withdrawal charges.

The former executive director's decision to place primary plan funds in restrictive securities limits the ability of 4Cs' employees to transfer their primary plan funds without incurring substantial withdrawal charges, as shown in Figure 5. As previously noted, fiduciaries are required to perform their duties in the best interest of participants and beneficiaries under ERISA. We found that the former executive director authorized the placement of the primary plan funds in securities with early withdrawal charges for the first 15 years, ranging as high as 14 percent in the first year.1 Yet both the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission recommend investing in other types of retirement plans, such as IRAs or employer‑sponsored 401(k) plans, before investing in restrictive securities. Employees who leave 4Cs with fewer than 15 years of service and wish to transfer their vested balances to retirement plans of new employers or into an IRA will have those balances reduced by early withdrawal charges as a condition of the transfers. Because we did not have access to the personal records of individuals who transferred retirement balances to accounts outside of 4Cs, we were unable to identify actual instances of individuals incurring the charges or the amounts of those charges.

Figure 5

4Cs' Purchase of Restrictive Securities Resulted in Significant Withdrawal Charges to Some Employees and Ongoing Commissions to Its Financial Adviser

Sources: Primary plan documentation provided by 4Cs and investment information from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

We asked 4Cs to explain why its former executive director directed the placement of primary plan funds in restrictive securities. Its interim executive director was unable to answer our questions, stating that 4Cs had provided us with all of the documents in its possession that we requested, including documentation it had requested from its retirement plan administrator and financial adviser. He also deferred any perspective regarding this issue to 4Cs' legal counsel, who is currently in the process of addressing retirement plan issues pertaining to the lawsuit. Because these issues are pending in federal court, the legal counsel did not provide us with any additional information, and we do not reach any legal conclusions on those matters that are the subject of that litigation.

4Cs Could Not Demonstrate That It Met Applicable Reporting Requirements for Its Primary Retirement Plan

4Cs could not demonstrate that it complied with federal reporting requirements to provide participants and beneficiaries with standard retirement plan disclosures, such as information on the source of the primary plan's funding. ERISA requires employer‑sponsored plans to provide certain information to participants in summary plan descriptions (SPDs), retirement benefit statements, and annual reports. We reviewed 4Cs' retirement plan documents for plan years 2014–15 through 2016–17 to determine whether 4Cs complied with these disclosure requirements, and we determined that the SPDs that 4Cs prepared for each of these fiscal years did not contain the source of financing of the plan, a specific requirement of ERISA. Furthermore, it could not demonstrate that it met the requirement to provide the SPD annually to all participants and beneficiaries for any of the plan years we reviewed. 4Cs also did not provide other required information in its retirement benefit statements for plan years 2014–15 and 2015–16, such as the total benefits accrued and the vested benefits available to participants. Without having all required disclosures available regarding the primary plan, participants and beneficiaries may not have been able to make informed decisions about their retirement planning.

In addition, 4Cs did not submit its annual report for its 2014–15 plan year to the U.S. Secretary of Labor within 210 days of the close of the plan year, as federal regulations require. Specifically, 4Cs filed this report 193 days late. 4Cs did not provide an explanation for the missing information from the SPD and retirement benefit statements, and the late filing of the annual report. As mentioned previously, 4Cs' interim executive director informed us that his organization had provided us with all of the documents in its possession that we requested, including documentation it had requested from its retirement plan administrator and financial adviser. He again deferred any perspective regarding this issue to 4Cs' legal counsel, who is currently in the process of addressing retirement plan issues pertaining to the lawsuit. Because this issue is currently being litigated, the legal counsel did not provide us with any additional information, and we make no legal conclusions on this issue.

4Cs Engaged in Questionable Practices in Administering Its State‑Funded Supplemental Retirement Plan

According to available documentation, 4Cs established a supplemental employee retirement plan (supplemental plan) in 2006 to increase retirement benefits for certain employees to a level comparable to those received by participants of the California State Teachers' Retirement System (CalSTRS). 4Cs' legal counsel at the time we conducted our audit fieldwork stated that 4Cs established the supplemental plan as a top hat plan maintained by 4Cs for the purpose of providing deferred compensation for certain eligible employees. Such plans are defined in ERISA as unfunded and for the benefit of a select group of management or highly compensated employees. When properly established and maintained, a top hat plan is exempt from many of the legal requirements that ERISA imposes on qualified employer‑sponsored pension plans, such as the primary plan. These include certain requirements concerning participation and vesting, funding, and fiduciary responsibility. To qualify for these exemptions, top hat plans must limit participation to a select group of management or highly compensated employees. Table 2 illustrates some of the differences between 4Cs' primary and supplemental plans. To participate in 4Cs' supplemental plan, employees must be 60 or older and have completed at least five years of employment at 4Cs, although there is no specific requirement in the plan's provisions for the employee to be in management or to be highly compensated. In fact, the employees who already opted to participate in the supplemental plan do not appear to have been in management positions or to have been highly compensated. If the plan does not meet either requirement, it would be subject to ERISA funding requirements. The employees must also choose to receive their benefits from the primary plan over a 20‑year period and elect to participate in the supplemental plan within six months of terminating their employment at 4Cs. When an individual elects to participate in the supplemental plan, 4Cs authorizes an amount to be transferred from that plan to a separate retirement account administered for that person.

| Features | Primary Plan | Supplemental Plan |

|---|---|---|

| Plan Type | Defined Contribution Plan | Deferred Compensation Plan |

| Participation Requirements | Employees qualify to participate in the plan upon reaching age 18* and completing one year of service. | Employees can elect into the plan within six months after termination of employment if they are 60 or older and complete at least five years of service. |

| Contribution Amount | 4Cs' board of directors annually approves the employer contribution (7% of employee salary in 2015 and 2016, and 4% in 2017). Employees do not contribute to the plan. | Employer contributions are determined by the board based on available funding. Employees do not contribute to the plan. |

| Contribution Frequency | Contributions are made monthly to each participant's account.† | Contributions are made sporadically to a pooled account based on the board's decision (no contributions since 2009). |

| Benefit Disbursement Process | Employees are entitled upon retirement to receive the balance in their accounts as a lump sum payout or to transfer it to an annuity or another retirement plan. | Lump sum amount is transferred from the pooled account to a separate retirement account for the individual with fixed monthly payments over 20 years. |

Sources: Primary and supplemental plan documentation provided by 4Cs, and confirmations with 4Cs management.

* The ERISA requirement differs from 4Cs' requirement in that it specifies a minimum age of 21 to participate in the plan.

† Employees may roll over contributions from another qualified plan or individual retirement account into the primary plan.

The amount to be transferred for each participant appears to be based on a calculation of the monthly benefit amount for that individual. That amount is determined by identifying the monthly benefit the employee would be entitled to receive if he or she were a CalSTRS participant and then subtracting the monthly benefit the individual currently receives from the primary plan to arrive at the difference, which is the monthly amount needed from the supplemental plan. However, we were unable to verify the reasonableness of the amounts that have been transferred because 4Cs did not maintain any documentation to support the relevant calculations, and its current staff have no knowledge of how these amounts were determined.

4Cs may have improperly used education grant money to fund its supplemental plan. State regulations and Education's contract terms allow 4Cs, as an Education contractor, to use state grant funds for employee benefits, subject to the uniform cost principles. These cost principles require the contractor to fund costs for all plan participants within six months of the end of the plan year. However, 4Cs never specified any plan participants for the supplemental plan and instead pooled all of the money of the supplemental plan into a single account. Additionally, 4Cs could not provide us with documentation to identify the frequency, amounts, or funding sources of the contributions it made to the plan. However, 4Cs' financial statements indicate that it used public funds for its supplemental plan. In 2009, the most recent year that 4Cs contributed to the supplemental plan, 95 percent of 4Cs' revenue came from public funding—72 percent from state funds and 23 percent from federal funds—leading us to conclude that nonpublic revenue would not have contributed much, if any, to the supplemental plan. Further, although 4Cs' accounting manager stated that 4Cs does not have any documentary evidence of how it funded its supplemental plan, he agreed that it is highly likely that most of the funding came from state funding sources.

Unlike the fixed monthly contributions to the primary plan that 4Cs makes for employees based on their compensation, 4Cs appears to have contributed to the supplemental plan sporadically and in varying amounts. Based on background information provided for a board meeting, discussions about the supplemental plan were taking place as far back as January 2004. A presentation from the financial adviser serving as 4Cs' agent for the supplemental plan indicates that the balance of funds in the supplemental plan was approximately $1.1 million in December 2009. According to the former executive director of 4Cs, the most recent contributions to the supplemental plan were in 2009. At the time 4Cs established the supplemental plan, only two employees, including the former executive director, who was head of the organization during that time, met the age and service eligibility requirements.

4Cs' supplemental plan documentation states that the purpose of the plan is to supplement the primary plan and provide a retirement benefit comparable to that of CalSTRS. However, 4Cs did not conduct any analysis to quantify the amount needed to cover the costs of such a plan, which we consider essential for establishing the financial viability of the plan. We expected that such an analysis would include an estimation of the number of employees who would be eligible and expected to participate and a calculation of the amount 4Cs would have to invest to provide a CalSTRS‑equivalent benefit to those employees. Further, we expected to see calculations that would specify key assumptions relevant to the benefit payouts, such as the average years of service, average age at retirement, and average salary that the benefits would be based on. That analysis should also have included a funding schedule to ensure that sufficient assets would be on hand to fund the benefits of all eligible participants. Instead, 4Cs informed us that it funded the plan only as surplus funding became available and that its financial adviser directed 4Cs on the specific amounts to be transferred. However, it was unable to provide us with any documentation supporting how the financial adviser determined those amounts.

4Cs provided records that show that five employees besides the former executive director were eligible and elected to participate in the supplemental plan from 2011 through 2017. For each employee, 4Cs transferred an amount between $40,000 and $102,000 to a separate retirement account at the time of each election. In total, 4Cs transferred approximately $427,000 from the supplemental plan. 4Cs initially informed us that the supplemental plan is currently suspended, but that it will allow individuals who are eligible within a year of the suspension of the plan to elect participation. However, when we requested clarification about when the suspension took effect and the dates that individuals would still be eligible to participate, 4Cs' management was unable to answer our questions. Nevertheless, based on the age and years‑of‑service criteria mentioned previously, it appears that as of September 2017, the only individual who was eligible to participate in the plan was the former executive director.

Table 3 shows that if the former executive director successfully enrolls in the plan, 4Cs will have to liquidate the balance of its supplemental plan. In contrast to the relatively modest amounts 4Cs transferred for the other participants, the former executive director would be eligible for more than $2 million from the supplemental plan. Because the plan's remaining balance was only $1.3 million as of February 2018, his participation will leave nothing remaining for other employees who may subsequently become eligible for that plan.

| Calculation of the Amount of the Supplemental Plan Balance Needed to Provide a CalSTRS‑Equivalent Benefit for 20 Years |

|

|---|---|

| Monthly supplemental plan benefit | $16,681* |

| Starting principal needed to provide the monthly benefit for 20 years | $2,538,056† |

| Less the amount the former executive director receives from the primary plan | – 528,211 |

| Amount needed from supplemental plan | = $2,009,845 |

| Less the supplemental plan account balance as of February 9, 2018 | – 1,280,762 |

Sources: CalSTRS Retirement Benefit Calculator, supplemental plan documentation, primary plan documentation, and present value of an annuity calculation.

* Assumptions of 44.85 years of service, an average monthly salary of $15,125, an age factor of 2.4% (the percent of final compensation for each year of service credit), and a monthly longevity bonus of $400 (a benefit for CalSTRS members with 30 years of service prior to December 31, 2010).

† Assumptions of 5% interest (the maximum amount credited to annuities for the specific annuity type purchased by 4Cs) and 240 monthly payments of $16,681.

4Cs was unable to inform us whether the former executive director enrolled or plans to enroll in the supplemental plan. The supplemental plan's requirements state that participants must enroll in the plan within six months of separating from the organization. Because the former executive director retired on August 7, 2017, he would have had to enroll in the supplemental plan by February 7, 2018, to receive those funds. Although 4Cs provided evidence that the balance of $1.3 million remained in the plan as of February 9, 2018, this reported balance alone is insufficient to determine whether the former executive director had already enrolled in the plan because it does not account for the processing time required by 4Cs to transfer balances and issue initial payments. In fact, one of the other five individuals who enrolled in the supplemental plan did not receive an initial payment until nearly five months after she had submitted her request to enroll in the plan. More significantly, 4Cs allowed two participants to enroll in the plan after the purported deadline, with one enrolling in the plan three months after the six‑month time frame had elapsed and another enrolling more than a year after the six‑month time frame had elapsed. Therefore, it is unclear that 4Cs would deny a request by the former executive director to enroll in the plan, even after February 2018.

Additionally, we determined that 4Cs' financial adviser also assisted with establishing the supplemental plan by recommending to the 4Cs board that it use its supplemental plan contributions to purchase restrictive securities. As such, the assets in the supplemental plan are similarly subject to the substantial withdrawal charges associated with the securities in the primary plan.

We requested further clarification from 4Cs as to why it placed the supplemental plan funds in restrictive securities, but 4Cs could not provide any rationale for why it did not question the financial adviser's recommendation. As mentioned previously, 4Cs' interim executive director deferred any perspective regarding this issue to 4Cs' legal counsel, who is currently in the process of addressing retirement plan issues pertaining to the lawsuit. Because these issues are pending in federal court, the legal counsel did not provide us with any additional information, and we do not reach any legal conclusions on those matters that are the subject of that litigation.

Recommendations

4Cs

To ensure that beneficiaries do not have restrictions limiting their ability to transfer their retirement funds, 4Cs should, by October 2018, move the funds for its primary and supplemental retirement plans out of the restrictive securities to the extent possible without incurring additional charges for beneficiaries. For any subsequent new participants, 4Cs should assign funds only to securities that do not have extensive charges associated with transferring or rolling over the funds.

To ensure that its retirement plan participants can make appropriate financial planning decisions, 4Cs should provide the required disclosures in its retirement benefit statements, summary plan description, and annual report, and it should maintain documentation that it did so.

Education

To ensure the appropriate use of state grant funds, Education should determine, to the extent possible, the amount of supplemental plan funds that did not comply with federal requirements, and it should require 4Cs to reimburse the State for improper payments of state funds it made to the supplemental plan.

OTHER AREAS WE REVIEWED

To address the audit objectives that the Joint Legislative Audit Committee approved, we also reviewed the additional subject areas shown below. Here we indicate the results of our review and any associated recommendations we made that we do not discuss in other sections of this report.

Unlawful Harassment and Anti‑Retaliation Policies

- 4Cs does not have a specific anti‑retaliation policy, as state regulation requires. In addition, 4Cs' personnel policies lack several pieces of information pertaining to retaliation that federal guidance suggests that employers include. Specifically, federal guidelines suggest including examples of retaliation, proactive steps for avoiding actual and perceived retaliation, and guidance on interactions between managers and employees. Aside from a single reference in its unlawful harassment policy that 4Cs does not tolerate retaliation against an employee for cooperating in an investigation or for making a harassment complaint, its policy manual does not address that guidance.