Use the links below to skip to the Chapter you wish to view:

- CHAPTER 1—Flaws in CJP's Intake and Investigation Processes Could Allow Judicial Misconduct to Continue

- CHAPTER 2—CJP's Structure and Disciplinary Processes Do Not Align With Best Practices or the Intent of California's Voters

- CHAPTER 3—CJP Has Not Taken Critical Steps to Improve Its Transparency and Modernize Its Operations

Chapter 1

Flaws in CJP's Intake and Investigation Processes Could Allow Judicial Misconduct to Continue

Chapter Summary

Although adequately investigating complaints is critical to detecting and ending judicial misconduct, CJP's investigators have failed to pursue allegations thoroughly and ignored warning signs of ongoing misconduct. In about one-third of the 30 cases we reviewed, investigators did not take all reasonable steps—such as speaking to critical witnesses or reviewing pertinent records—that could have helped CJP determine the existence and extent of the alleged misconduct. In three cases, CJP did not identify indications of potential long-running misconduct—the filing of several similar complaints about the same judge—in either its intake or its investigative stages. Although CJP generally followed a reasonable process for reviewing new complaints, its intake attorneys did not identify patterns of allegations against specific judges because CJP has not established a formal process to monitor for such trends. Similarly, its investigators did not adequately consider trends in prior complaints against specific judges, and consequently they did not seek approval from the commission to expand their investigations to determine whether larger problems existed. The weaknesses we observed in CJP's investigations are likely due in part to its lack of key safeguards for ensuring high quality investigations, such as documented investigation strategies and adequate managerial oversight.

In About One-Third of the Cases We Reviewed, CJP's Investigators Did Not Take All Reasonable Steps to Determine the Existence or Extent of Alleged Misconduct

As the Introduction describes, if a complaint advances past the intake phase, CJP charges its investigators with determining whether judicial misconduct occurred and recommending that the commission either issue discipline or close the case. A team of six investigators conducts all CJP investigations. Pursuant to a 1973 Supreme Court decision, the commission can impose discipline only if there is clear and convincing evidence of judicial misconduct. In other words, CJP must demonstrate that a finding has a high probability of being true. The frequency with which the commission agrees with its investigators' recommendations heightens the importance of their work being thorough. From fiscal years 2013–14 through 2017–18, the commission agreed with more than 70 percent of the discipline recommendations its staff made. As Figure 7 shows, CJP closed 75 percent of its investigated cases without discipline.

Figure 7

CJP Closes Most Cases That It Investigates Without Issuing Discipline

Source: Analysis of data from CJP's case management system.

After reviewing 30 investigations that CJP concluded during our five-year audit period, we determined that it did not take all reasonable steps to determine the existence or extent of alleged misconduct in 11 investigations. Once the commission approves an investigation—the frequency of which we discuss later in this chapter—investigators have wide latitude to take the actions needed to evaluate potential misconduct. According to the director-chief counsel (director), investigators may speak with court staff, attorneys who practice before the judge, litigants, or the judge's peers, as well as observe court proceedings. They may also review many types of records, including court files, files from other government agencies, and phone and email records. State law requires other public entities to cooperate with and give reasonable assistance and information to CJP in connection with any investigation. State law also authorizes CJP to issue subpoenas to obtain records or witness testimony that is relevant to any investigation. However, as Figure 8 shows, investigators did not thoroughly investigate 11—or about one‑third—of the cases we examined, even though these investigations involved serious allegations.

Figure 8

CJP Did Not Thoroughly Investigate About One-Third of the Complaints We Reviewed

Source: Analysis of CJP investigative files, memos, and original complaints.

Note: Of the 11 cases not thoroughly investigated, six were closed without discipline and five resulted in private discipline.

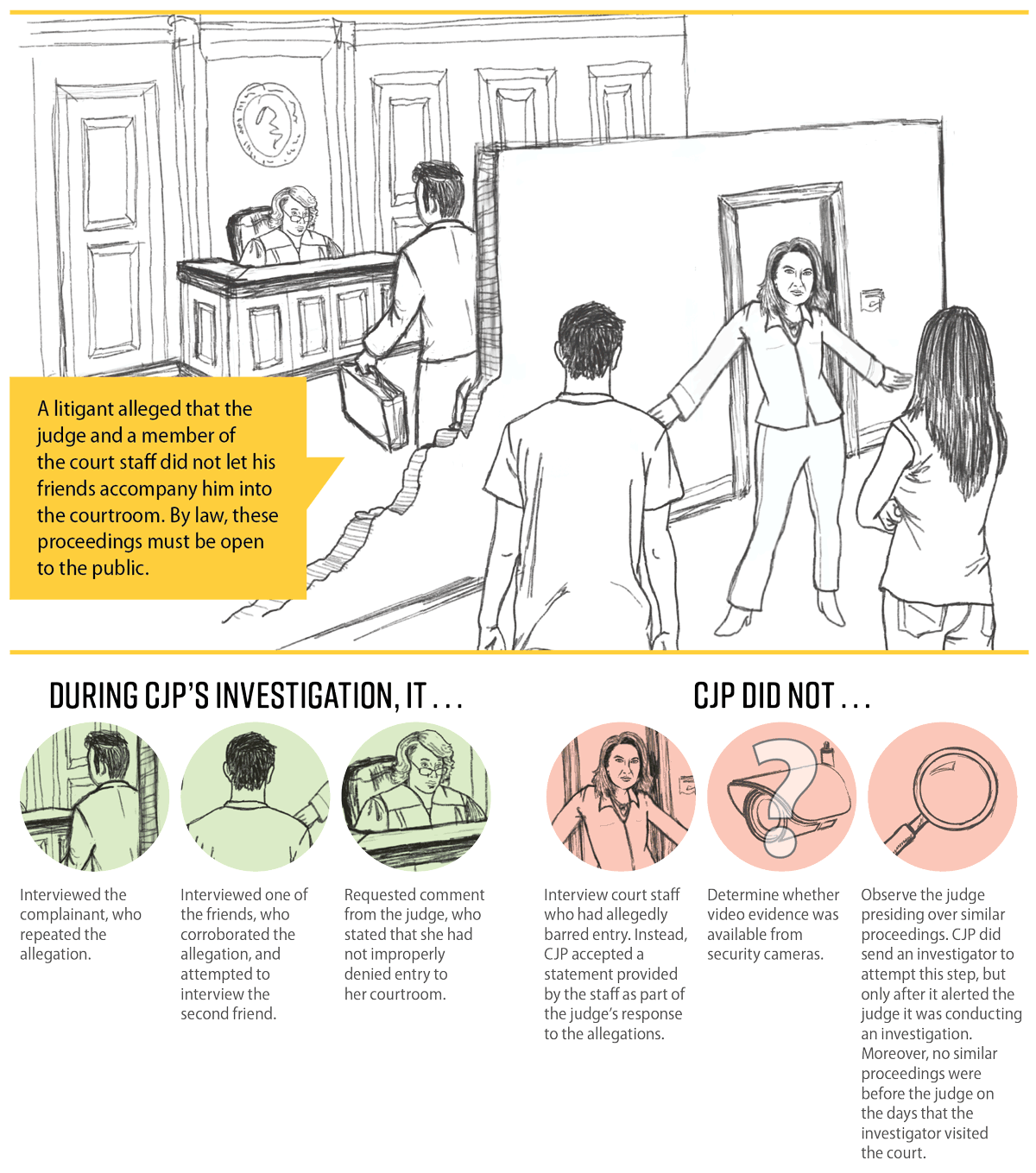

In some of these 11 investigations, CJP did not take investigative steps that would have increased the likelihood that it could identify whether judicial misconduct occurred. One such investigation involved an allegation that a judge and a member of the court staff restricted public access to a proceeding, which can be a violation of the law. Figure 9 illustrates the actions the investigator took to evaluate this allegation and the key steps he did not take. Ultimately, the commission closed the case without discipline. When we discussed the missed steps with the investigator, he expressed his belief that certain steps would not add value to the investigation, as well as his concern about the time and costs associated with courtroom observation. Because the investigator did not successfully execute all reasonable actions during his investigation, the risk is higher that if the alleged misconduct occurred—in this case, improperly barring the public from open proceedings—it did so without detection.

Figure 9

CJP Missed Key Steps in Its Investigation of a Judge's Alleged Misconduct

Source: Analysis of a CJP investigation file.

Note: We changed the gender of some of the parties to protect the confidentiality of the investigation.

In another example of an inadequate investigation—involving some of the most egregious alleged misconduct among the investigations we reviewed—CJP did not take a key step to determine the extent of a judge's misconduct. During this investigation, which involved a high number of allegations, the investigator learned that the judge allegedly made many aggressive and intimidating comments while on the bench. The investigator was told these comments may have crossed the line into criminal behavior. Court reporters told the investigator that they had some audio recordings of the judge's proceedings, that they thought they remembered the judge making inappropriate comments, and that they would attempt to listen to the audio to find examples of the judge's comments. However, according to the investigator, the court reporters later advised her that finding relevant audio recordings to identify specific improper comments was an onerous task, and they refused to do it. At that point, the investigator could have requested that the court reporters voluntarily provide her with audio files from proceedings before this judge so that CJP could listen to them. Instead, the investigator never requested the audio files.

When we asked the investigator why she did not request audio files that might have substantiated some of the allegations, she explained that she believed at the time that the high number and strength of the witness testimony she had collected would be sufficient to meet the clear and convincing standard for proving misconduct. She also expressed her concern that processing all of the court reporters' audio recordings would be time-consuming. However, she acknowledged that CJP could have brought in additional staff to assist. According to assistant trial counsel, CJP successfully used a similar approach in another investigation when it obtained and reviewed audio of a judge's inappropriate behavior that a court had recorded.

Using court transcripts and witness testimony as evidence, the commission ultimately disciplined the judge for some of these comments, but it closed several other allegations. However, trial counsel staff also did not request that the court reporters provide audio recordings. When we asked the assistant trial counsel who worked on the case why CJP did not request a selection of recordings, he was not sure whether CJP had asked for audio recordings or whether audio recordings even existed. CJP's director stated that he was not certain whether CJP could use its subpoena authority to obtain audio recordings from court reporters due to the legal protections around court reporter records, which make them different from audio recorded directly by a court. However, according to guidance from the Court Reporters Board of California, court reporters have discretion to provide their audio recordings to attorneys or involved parties. Moreover, state law also requires court staff to provide reasonable assistance to CJP investigations. The assistant trial counsel stated that this requirement would likely encompass court reporters. By leaving these issues unresolved and not requesting a selection of audio recordings, CJP left the extent of the misconduct undetermined.

In another example, CJP investigators confirmed that the judge had improperly delegated judicial authority by allowing court staff to perform certain duties. However, despite the fact that CJP visited the court more than once, investigators never interviewed the court staff who were involved in this improper practice. These staff might have provided valuable insight on the judge's involvement with the practice and its history. When CJP asked the judge about the improper delegation, the judge provided an initial explanation for the practice. CJP then notified the judge that the practice was improper and that it was considering issuing a private admonishment, which is a higher level of discipline than an advisory letter. In response, the judge provided a second explanation for the practice that contradicted the first. The commission ultimately issued an advisory letter. Nevertheless, because the investigators did not speak with the court staff, they could not give the commission any information those staff may have been able to provide, which might have aided the commission when it assessed the judge's changing explanations.

The steps investigators do or do not take can affect the disciplinary decisions that the commission can make. We did not reweigh evidence in these cases or second-guess the propriety of the commission's determinations based on the facts that the investigators presented to it. However, missed investigative steps like those we discuss in this section leave unanswered questions about the existence or extent of misconduct. These unanswered questions can have a direct, negative effect on the commission's ability to issue appropriate discipline because doing so requires that its staff find clear and convincing evidence of misconduct.

CJP's investigators generally shared their perspective that the investigative techniques that we believed were reasonable would not have benefited the investigations. We disagree. The investigators used many of these same investigative techniques—such as reviewing video and audio recordings and interviewing court staff—in other investigations, and the steps proved to be beneficial. Therefore, we believe that these steps were worth taking.

Some courts' lack of transcripts and recordings could also potentially hinder CJP's ability to prove misconduct with clear and convincing evidence. Our review of four superior courts found that the availability of official court reporters and electronic courtroom recordings varied by county and by the type of court case, as Table 1 shows. The four courts we reviewed each asserted that they provide some court reporter or courtroom recording services, with Los Angeles, Sacramento, and San Francisco superior courts providing these services for a variety of case types. In contrast, Glenn Superior Court asserted that it provides court reporters in only four case types. Because the availability of court reporters and electronic recordings for case types differ, CJP might not be able to obtain transcripts or electronic recordings for certain cases, depending on a local court's practices.

Among the 16 investigations we reviewed in which transcripts or recordings would have helped to prove or disprove misconduct, a lack of transcripts or recordings hindered CJP's ability to obtain clear and convincing evidence of judicial misconduct in three instances. According to the supervising administrative specialist, CJP has not comprehensively tracked in its case management system the cases in which transcripts or recordings were unavailable, impeding it from being able to demonstrate that a lack of transcripts is a widespread problem. In 2012 CJP sent a letter to the Legislature, the Governor, and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court expressing concern that many courts were responding to budget cuts by eliminating court reporter services. Additionally, in 2016 CJP's former director testified before an Assembly Budget Subcommittee that very often CJP could not meet its clear and convincing standard of evidence for proving misconduct because of a lack of court recordings and transcripts. If CJP believes the absence of court transcripts or recordings regularly impedes its ability to conduct investigations, it should expand its efforts to inform policymakers that increased use of transcripts and recordings in California court proceedings would improve its ability to fulfill its mission.

| Case Type | Sacramento | Los Angeles | San Francisco | Glenn |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criminal felony | ||||

| Criminal misdemeanor | ||||

| Unlimited civil† | ||||

| Limited civil† | ||||

| Juvenile | ||||

| Family | ||||

| Criminal infraction | ||||

| Probate | ||||

| Traffic | ||||

| Unlawful detainer | ||||

| Small claims |

Source: Interviews with staff at all four courts and analysis of Los Angeles Superior Court's policies and procedures.

* Glenn Superior Court stated it only provides court reporters for certain cases of this type.

† If courts allow parties to pay for private court reporters in civil cases, then courts must provide an official court reporter for indigent litigants.

‡ Sacramento Superior Court has four court reporters who it assigns to family court cases with the highest likelihood of appeal.

§ San Francisco Superior Court stated that it provides court reporters for these case types only when they deal with a high volume of consecutive hearings.

In Both Its Intake and Investigative Stages, CJP Failed to Detect Warning Signs of Ongoing Misconduct

CJP's intake and investigative processes did not always consider trends in the complaints about specific judges, hindering CJP's ability to detect and deter chronic judicial misconduct. Although attorneys at the intake phase evaluate the facts and evidence that individual complainants provide, they do not always consider whether other complainants had filed similar allegations about the specific judges in question. Further, CJP has not established a process for intake attorneys to advise the commission on when to use its oversight authority to investigate potential chronic misconduct. We found similar problems with CJP's investigative phase: after reviewing investigations of judges with long histories of similar complaints, we found that it missed opportunities to expand the scope of investigations to determine if misconduct was representative of a larger, ongoing problem. CJP's failure to take proactive steps to identify chronic misconduct increases the risk that it will fall short in its duty to protect the public.

Although CJP's Intake Process Is Reasonable, It Does Not Identify Patterns of Complaints Related to Specific Judges

The fact that CJP investigates a small percentage of the complaints it receives has caused concern. However, we found that CJP has established a reasonable intake process for addressing individual complaints and that its intake attorneys have generally followed that process. As we describe in the Introduction, CJP requires that its intake attorneys assess complaints across two different factors: a legal review and a factual review. For an intake attorney to recommend that the commission open an investigation, the legal review must reveal that the complainant has alleged misconduct and the factual review must determine that facts or evidence could exist to warrant an investigation. Similar to investigations, the frequency with which the commission agrees with its intake attorneys' recommendations to close cases before conducting investigations shows the importance of the work they perform. In fact, during meetings CJP held from fiscal years 2013–14 through 2017–18, the commission only disagreed with the intake attorney's recommendation to close a complaint without investigation in 11 of about 5,100 instances. During this same period, CJP closed at intake about 85 percent of the almost 6,000 complaints it closed.

We reviewed 40 complaints that CJP closed without investigation after its review at the intake stage from fiscal years 2013–14 through 2017–18. Legal and factual reviews in these cases were often intertwined. For example, CJP's ability to determine a fact—such as the type of hearing in which a judge allegedly made a comment—can affect its ability to determine whether the alleged behavior would be misconduct under the ethics code. In other words, the context for alleged behavior can be important to CJP's assessment of complaints at intake. Sometimes the absence of potentially relevant facts means that intake attorneys do not forward complaints to the commission with a recommendation to investigate the complaint. The manner in which CJP keeps its records made it difficult for us to determine with precision how many complaints the commission did not forward to investigation specifically because the complaints failed the legal or factual review. However, we do not have concerns about CJP's record keeping because these two analyses are often interconnected. Additionally, we were able to determine the reasons intake attorneys recommended the commission close complaints by reviewing the memos they sent to the commission and discussing the complaints with the attorneys.

Thorough factual review often requires that intake attorneys take steps beyond reading the original complaint and its attached materials. Additional fact checking steps help the attorneys answer questions regarding complainants' allegations before making recommendations to the commission. We found that the intake attorneys performed these additional steps in about half of the 40 complaints we reviewed. However, additional steps are sometimes unnecessary. For example, attorneys do not need to complete additional factual review steps when a complainant makes an allegation that does not constitute misconduct or sends CJP supporting documents that do not corroborate the allegation.

However, we are concerned that CJP's intake process does not identify patterns of complaints that—taken in the aggregate—could point to potential judicial misconduct that it could investigate under its oversight authority, which empowers it to initiate investigations as it deems necessary. In one particularly concerning example, CJP's failure to identify patterns of allegations allowed a judge who was the subject of many similar complaints of serious on-the‑bench misconduct to avoid discipline for years. Figure 10 provides a timeline of the relevant complaint history for this judge. CJP did not open investigations into many of these complaints because it concluded the allegations either did not constitute misconduct or were unlikely to be provable. During the investigation of one early complaint it did investigate, the judge admitted to improper behavior and promised not to repeat the behavior. The commission closed the case without discipline. The last complainant alleged that the judge had again engaged in similar behavior and supported his allegations with transcripts. CJP opened an investigation, and the judge offered to resign and agreed in a confidential settlement to never again serve in a judicial capacity.

Figure 10

Despite Numerous Complaints About a Judge's Actions, CJP Did Not Detect a Pattern of Misconduct

Source: Analysis of CJP case files, complaints, and database.

Note: This timeline includes only complaints that we determined to be related to the type of misconduct for which CJP eventually disciplined the judge. CJP received additional complaints about this judge during the same time period, but those complaints alleged different types of misconduct or did not allege misconduct.

Although the final investigation ended with the judge leaving the bench, the fact that CJP did not detect a pattern of inappropriate activity earlier in this five-year period raises concerns about how it approaches its oversight of judicial misconduct. The last complainant attached transcripts to the complaint that were instrumental in proving misconduct occurred. In other words, CJP had no challenges meeting the factual analysis portion of the intake evaluation and did not need to perform an extensive investigation. However, had the complainant not provided these transcripts, it is not clear whether CJP would have opened an investigation into the related allegations or once again closed the matter at intake as it had with some of the previous complaints. Upon reviewing the pattern of complaints, one of CJP's assistant trial counsels—who is among its most senior attorneys—agreed that the allegations in two of the past complaints warranted more thorough investigations. CJP's current process does not require intake attorneys to review past complaints for patterns of misconduct, unless they are recommending the commission open an investigation.

Further, at intake, CJP's data do not allow it to identify patterns of complaints related to judges' legal errors. As the Introduction describes, legal errors are rulings that constitute legal mistakes. Legal errors that changed the outcome of a case must be resolved by a reviewing court. The Supreme Court has ruled that mere legal error is not sufficient to find that a judge violated the ethics code. However, CJP's rules indicate that legal error paired with a violation of the ethics code—such as bias—is subject to investigation and discipline. Analyzing data on complaints about legal error during intake could help CJP identify additional factors that might constitute misconduct and warrant an investigation. For example, the director of the state of Washington's judicial conduct commission stated that Washington reviews a judge's complaint history to determine whether a judge has committed a pattern of legal error that infringes on basic rights. Additionally, analyzing complaints could reveal whether a judge consistently commits legal error in cases involving litigants of a certain protected class of people, which could indicate bias. Analysis of complaint data in this manner would be consistent with the Supreme Court's observation that a judge may commit acts that lead to violations of the ethics code through repeated legal error. As an example, the Supreme Court indicated that a judge who repeatedly dismisses certain claims might be subject to discipline if the dismissals are shown to be not only legally erroneous, but also based on bias, prejudice, or some other improper purpose.

However, CJP lacks the data it needs to identify these patterns. Specifically, because of its data entry practices, CJP cannot generate a report of all judges about whom it has received complaints of legal error. CJP's intake manager told us that when it closes a complaint at intake, an attorney would likely use an allegation code that documents a complainant's dissatisfaction with a judicial act if at least one of the allegations concerns legal error. However, she also explained that attorneys use this same code for matters in which the complainant does not allege any legal error. In fact, CJP applied this code to about 5,400 of the more than 7,400 unique complaints it closed—or 73 percent—from fiscal years 2013–14 through 2017–18. We found this approach particularly concerning because CJP has five other allegation codes that more specifically relate to legal error, which it used for just over 150 complaints that it closed during the period we reviewed. In our review of 25 complaints indicating legal error, we were unable to identify any patterns of misconduct by specific judges. However, CJP's imprecise data limited our analysis and will limit CJP's ability to perform analyses as well, because it cannot identify all complaints related to legal error.

Ultimately, the commission will likely need to use its oversight authority—its ability to open investigations that do not stem from a single complaint—if it wishes to open investigations when it identifies patterns of potential misconduct. Currently, CJP's procedures state that it will use its oversight authority to investigate matters that it learns about from anonymous complaints, from its commissioners, from news articles, from appellate decisions, or from its work on other cases. To better leverage its oversight authority so that it can address patterns of misconduct, CJP would need to define when trends in complaints constitute possible misconduct and direct its intake attorneys to recommend oversight investigations under those circumstances.

CJP's Narrow View of Investigations Stopped It From Identifying Potentially Chronic Misconduct

We observed that CJP investigators sometimes took a narrow view of their investigations. Consequently, they did not always consider the broader histories of allegations against judges when determining how to conduct their investigations and whether to recommend that the commission impose discipline. When we reviewed 30 investigations, we identified two in which patterns of previous complaints about the judges in question suggested that the alleged misconduct might have been chronic. We believe that both of these cases warranted investigations that were broader in scope than the investigations CJP conducted.

In the first case, CJP received 12 complaints about the judge's demeanor and bias on the bench over the course of fewer than 10 years. However, it did not take steps to investigate the complaints as a pattern. The investigation we selected for our review involved the fifth complaint that CJP received regarding this judge about these types of misconduct. This complaint alleged that the judge had displayed poor demeanor and showed favoritism during a court proceeding. CJP staff spoke with the complainant and a witness before the investigator determined that he could not prove the allegations contained in that specific complaint. The commission closed the complaint without issuing discipline.

According to the investigator, he could have expanded the scope of his review so that he could determine whether a systemic problem with the judge's behavior existed. He stated that he could have employed techniques—such as interviewing a selection of attorneys who routinely practice before the judge or interviewing court staff—that CJP's investigations manual suggests for investigating patterns of misconduct. Because of the time that elapsed since the investigation, the investigator for this case did not recall why he chose not to expand the scope of his investigation, but he also stated that he nevertheless believed it was reasonable for him to conduct his investigation in the manner in which he did. We find this perspective puzzling, given that CJP received two additional complaints about related behavior about the same judge while CJP was reviewing this complaint. One of these complaints alleged that the judge behaved in an almost identical manner as was alleged in the case being reviewed. In the three years following the commission closing this investigation, CJP received five additional complaints about the same judge's demeanor or bias.

In the second case, shortcomings in the investigation stopped CJP from being able to determine whether the misconduct had reoccurred. The commission had privately disciplined the judge in question three times for inappropriate remarks. During the period we reviewed, CJP received another complaint about the judge making improper remarks—which at the time was the eighth complaint it had received over a 12 year period that alleged the judge displayed poor demeanor. The commission opened an investigation. Despite the judge's history of prior complaints and discipline, the assigned investigator ended her investigation after she determined that there was not a transcript of the relevant proceeding and that witnesses could not corroborate the misconduct alleged in that specific complaint. However, she could have conducted courtroom observation—which CJP had used in a previous instance to discipline the same judge—to attempt to determine whether misconduct was reoccurring. The commission closed this case without issuing discipline.

Given the history of discipline and similar complaints, we believe the investigator missed an opportunity to determine whether a broader pattern of misconduct existed. The investigator stated that there are generally no transcripts for proceedings before this judge—a situation she described as a conundrum. However, this situation means that the investigator's approach to proving misconduct was unlikely to ever result in clear and convincing evidence. In light of that fact, we believe that the investigator should have recognized the broader context of the judge's history of complaints and discipline and taken additional steps as necessary to determine if misconduct had occurred.

The director generally agreed that it was possible to do more investigative work in many cases. However, he asserted that investigators might have had reasons for not continuing investigations, including that their knowledge and experience led them to believe that additional investigative work would not yield better evidence of misconduct. He also suggested that because investigative resources are finite, devoting time to one case is a mistake if the time would be better spent on other cases. Notwithstanding the director's perspective, we believe that CJP's records for the judges in these two cases should have indicated to investigators the need to pursue broader investigations. Further, as we discuss later in this chapter, CJP's investigators did not prepare any investigative strategies for the cases we reviewed and had no established timelines for how long investigations should last. In the absence of these steps, we question whether CJP could have made fully informed, resource-based decisions to end these investigations.

By updating its procedures, taking a more comprehensive approach to its investigations, and leveraging all available information from past complaints, CJP could better investigate and detect judicial misconduct. As the preamble to the ethics code describes, our legal system is based on the principle that an independent, fair, and competent judiciary will interpret and apply the law. The ethics code seeks to ensure such a judiciary by establishing standards for judges' ethical conduct. Therefore, CJP's role as the sole agency responsible for investigating alleged violations of the ethics code is essential to upholding the integrity of the judiciary and public confidence in the judicial system. When it does not conduct adequate investigations, CJP falls shorts of its fundamental charge.

CJP Has Not Established the Safeguards Necessary to Ensure Effective Investigations

CJP must improve its internal safeguards to ensure that investigators do not omit valuable steps in the investigative process. For example, both best practices and CJP's internal procedure manual suggest that before commencing investigations, investigators should prepare their planned strategy for each case. According to the Council of Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency's Quality Standards for Investigations, an investigator should establish case-specific priorities and objectives in an investigation plan as soon as possible after the investigation's initiation.4 Similarly, best practice advice presented at an American Bar Association conference in 2013 recommended that an investigator prepare a preliminary investigation plan to document an internal investigation's objectives and preliminary timeline.5 CJP acknowledges the benefit of these types of plans in its investigation manual, which states that an investigator should outline an investigative strategy as soon as possible after receiving a case and that documenting this strategy in a memo is helpful.

However, CJP's investigators could not demonstrate that they prepared strategies for any of the 30 cases we reviewed. When we asked investigators why this was the case, we received a variety of responses. One investigator told us that she viewed one of her investigations as generally straightforward; therefore, a strategy was unnecessary and not a good use of her time. Another investigator told us that she uses other techniques to decide how to approach her investigations, such as reviewing the witnesses and documents that are mentioned in the intake attorneys' assessments of the complaints. However, the number of cases in which investigators failed to perform valuable steps, such as interviewing witnesses, suggests that they would benefit from spending additional time planning their approaches.

CJP also has not established any formal timelines for its investigations, which may have contributed to the wide variation in the time it spent investigating cases. For the 30 investigations we reviewed, the time between when the commission authorized an investigation and when the investigator made a final recommendation to the commission ranged from about two months to almost three years, with an average of 10 months. The director explained that a number of factors could affect the timeline of an investigation, such as whether CJP needed to wait for a court case to conclude or for the ruling of an appellate court. Further, in the cases we reviewed, the commission almost always granted judges' requests for extensions of time to submit their responses to allegations. Although some delays in investigations may be unavoidable, requiring investigators to develop estimated timelines as part of their investigative strategies would help CJP ensure that its investigations progress in a timely manner.

In addition, we believe that increased supervisory review is necessary to prevent missed investigative steps in the future. The director—who currently serves as the only level of supervision over investigators—indicated that he reviews drafts of the memos investigators prepare for the commission describing investigations before CJP mails those memos to the commissioners. After the memos have been sent to the commission, the director meets with investigators to discuss these memos in preparation for commission meetings. Additionally, some of the investigators stated that before the commission's meetings, the investigators prepare case status reports for the director describing the actions they have taken to date and their planned next steps for their cases. The director reviews these status reports and asks questions about the status of cases as needed.

Although we acknowledge that these steps may provide the director with some level of familiarity with the progress of investigations, the timing and frequency of these status reports and memo reviews mean that the director is not likely to catch gaps in investigative approaches in a timely manner. Specifically, the memo review meetings occur after the commission has already received the investigators' memos, which include recommendations about how to proceed with their cases. Further, these activities occur only before commission meetings, which take place about seven times a year. The director also explained that if an investigation presents complex or unique issues, he will discuss the case with the investigator to whom he is assigning it and that the investigator can meet with him about the case as it progresses. Although this process has obvious benefits, the director stated that it only happens with cases that CJP considers complex, leaving cases that it considers more straightforward unaddressed.

A more effective supervisory structure would employ a dedicated manager to supervise the investigators and review, approve, and monitor their investigative strategies and progress. The director would in turn supervise this investigations manager. This structure would be more consistent with CJP's approach to intake, in which it assigns an investigator as a supervisor over its intake staff, and it would also be in alignment with reasonable approaches to quality assurance. If CJP were to implement such a supervisory position, the investigations manager could review and approve investigation strategies before investigators begin their work and monitor their progress against those strategies to ensure the timely completion of investigations. Ultimately, an investigations manager would ensure that key steps are planned and performed.

Further, we believe CJP would benefit from establishing a process that empowers someone other than the investigations manager to perform periodic quality control reviews of the investigations it conducts. Before this audit, CJP's investigation practices had never been subject to external review. Although the confidentiality of CJP's investigations makes regular external reviews of its practices potentially difficult, CJP could use its office of the legal advisor to review its investigative practices on a periodic basis. The legal advisor's role—which, according to CJP's policies, is limited to assisting the commissioners in their adjudicatory functions and cannot include participation in the investigation of complaints—means that the legal advisor is insulated from the investigative staff's day-to-day activities and well positioned to periodically review the quality of their investigations. Specifically, the legal advisor could review a selection of completed investigations, report to the commission about the results of that review, and recommend that the commission adopt changes to CJP's investigative practices if warranted.

Unless CJP improves its practices, judicial misconduct may continue undetected and uncorrected. As we discuss in this chapter, CJP has not always taken all reasonable steps when investigating allegations of misconduct. Moreover, it has not always effectively investigated patterns of allegations, creating opportunities for unethical judges to remain on the bench. As an agency charged with protecting the public and ensuring the public's confidence in the integrity of the judiciary, CJP must improve its efforts to detect and deter judicial misconduct.

Recommendations

To ensure that it adequately investigates alleged judicial misconduct, CJP should do the following by April 2020:

- Implement processes to ensure that for each of its investigations, CJP's management reviews and approves an investigation strategy that includes all steps necessary to substantiate whether misconduct occurred.

- Create and fill a new investigations manager position and task that individual with reviewing and approving investigative strategies, as well as overseeing the execution of those strategies.

- Expand the role of its legal advisor's office to include periodic reviews of the quality of closed investigations and, as warranted, to recommend changes to CJP's investigative practices.

To ensure that it leverages all available information to uncover misconduct, CJP should establish procedures by April 2020 for more regularly exercising its oversight authority to open investigations into patterns of potential misconduct. At a minimum, these procedures should require that intake attorneys assess complaints to identify when patterns of complaints merit recommending an investigation.

To allow it to detect potential judicial misconduct associated with legal errors, CJP should immediately direct its staff to use more appropriate allegation codes when closing complaints at intake. By October 2019, CJP should determine what data it will need to begin tracking so it can trend information—voluntarily provided by complainants—that could indicate complaints about legal error should be investigated because there is a risk that legal error is the result of underlying misconduct, such as bias. By October 2019, CJP should also develop procedures that indicate how often it will evaluate its data for such trends and establish guidelines for when trends warrant CJP staff recommending that the commission open an investigation. CJP should begin tracking that information and implement these procedures as soon as possible.

To prevent the risk that it will fail to detect chronic judicial misconduct, CJP should create and implement procedures by October 2019 that require an investigator to review all prior complaints when investigating a judge and determine whether the prior complaints are similar to the current allegations. Further, the procedures should require that if a pattern of complaints indicates the potential for chronic misconduct, the investigator must recommend that the commission expand the investigation.

Chapter 2

CJP's Structure and Disciplinary Processes Do Not Align With Best Practices or the Intent of California's Voters

Chapter Summary

Since its inception in 1960, the commission has served as a single body that investigates alleged judicial misconduct. However, changes to the California Constitution over the past few decades have assigned that same unitary body greater responsibility for disciplinary decision making. As a result of these changes, commissioners who make disciplinary decisions are also privy to unproven allegations from investigations, creating the risk that inappropriate information may affect their ultimate decisions. This structure is not aligned with judicial discipline best practices, which recommend a bicameral—or two-body—commission. Further, instead of hearing cases itself, the commission has delegated a significant component of CJP's disciplinary proceedings to a panel of judges. The commission's use of judges to review evidence and reach conclusions about other judges' misconduct falls short of the intent of Proposition 190 passed in 1994, which sought to increase the public's role in judicial discipline. Because CJP's foundational statute exists in the California Constitution, reforms to address these issues will require a constitutional amendment. An ideal amendment would reform the commission into a bicameral structure and require the commission to hear its own evidentiary hearings.

CJP's Unitary Structure Does Not Align With Judicial Discipline Best Practices

Although CJP was the first judicial oversight commission of its type when Proposition 10 created it in 1960, several subsequent changes to its authority and discipline options have left its structure out of alignment with judicial discipline best practices. Since its inception, the commission has served as a single body charged with the investigation of alleged misconduct. However, the commission's role in the disciplinary decisions that result from those investigations has grown over time, as Figure 11 shows. During this evolution, the commission has continued to serve as a single body even after major changes, such as a 1994 constitutional amendment that gave the commission the authority to censure or remove judges without the involvement of the Supreme Court. This unitary structure means that commissioners are involved in every aspect of each case, from intake and investigations through formal proceedings and final discipline. The Supreme Court has issued decisions concluding that CJP's investigative and adjudicatory structure does not violate judges' due process rights. Yet, these court decisions are decades old and rely in part on observations about CJP's structure that have since changed as a result of the passage of the 1994 constitutional amendment that increased the commission's adjudicatory authority. The unitary structure and the commission's involvement in all phases of a case pose potential problems for a judge's right to a fair hearing before a neutral decision-making body.

Specifically, the unitary structure allows commissioners who make disciplinary decisions to be privy to allegations of and facts about possible misconduct that should not factor into their decisions about discipline. We observed that CJP often pursues several allegations of misconduct within a single investigation but ultimately concludes that it cannot prove that all of the alleged misconduct occurred. In these cases, the commission makes a disciplinary decision about only the misconduct that it believes it has proven to the clear and convincing evidence standard. However, because the commissioners who make decisions about discipline were privy to information that CJP did not ultimately prove, there is heightened risk and potentially the perception that they may intentionally or unintentionally use that unproven information to reach conclusions about the appropriate discipline. Although it is not identical in nature, CJP's structure is analogous to a jury in a criminal case being composed of the detectives who investigated that case. As a result, the commission could potentially select a level of discipline that may be harsher or more lenient than the proven charges warrant.

In our review of 30 cases that resulted in public or private admonishment of a judge, we did not observe any instances in which the commission formally documented unproven information as support for its disciplinary decisions. Nevertheless, the commission does not document or record its deliberations, and CJP would never be able to assess any unspoken effects of the commissioners being aware of unproven allegations of misconduct. To support the appropriate level of discipline, the memos that staff prepared for the commission often referred to CJP's past decisions on similar misconduct. Using CJP precedent as a guide can serve to guard against the commission's decisions being too lenient or too harsh for a given misconduct. The commission could look at its prior decisions on similar misconduct to help it determine whether a particular level of discipline is appropriate. However, referring to precedent is effective as an approach only when the commission has made similar decisions in the past, which is not always the case.

Figure 11

CJP's Disciplinary Authority Has Grown Over Time Because of Constitutional Amendments

Source: Analysis of California constitutional amendments.

* Disciplinary authority to censure added as a result of voters passing a constitutional amendment in 1966.

Another weakness of the commission's unitary structure is that the commission could be perceived as having prejudged cases before the start of formal proceedings. If a judge demands formal proceedings in response to a notice of admonishment, the same commission that authorized the notice of admonishment—a clear indication that it believes discipline is warranted—ultimately decides whether to issue discipline at the conclusion of formal proceedings. In 1994 the American Bar Association published model rules for judicial disciplinary enforcement that were developed by a committee of experts from across the United States after researching judicial discipline commissions in 12 states, including California. These model rules highlight that one of the most consistent complaints the committee heard from judges and their attorneys was the perceived unfairness of a system that combines investigation, prosecution, hearing, and decision making into a single process. Specifically, once a commission is exposed to all the investigative information and files formal charges, judges believed that it is nearly impossible for the same commission to be a neutral adjudicative body and that the appearance of fairness is not met.

To address these types of concerns, best practices recommend a bicameral structure for judicial oversight commissions that separates the functions of investigating and disciplining judges—an approach that 17 states have implemented. Figure 12 shows how a bicameral structure ensures that a commission bases its disciplinary decisions only on proven misconduct. The model rules recommend a smaller investigative body and a larger hearing body, with separate legal counsel responsible to each. Under this composition, no member of a commission is involved both in deciding whether to file formal charges and in hearing the case resulting from those charges.

Although we believe the American Bar Association model rules present a best practice for structuring CJP, we do not believe California should adopt a related portion of the model rules. Specifically, the American Bar Association recommends that a state's highest court impose judicial discipline. For a large part of CJP's existence, the Supreme Court served in that capacity for removals and censure. In fact, the Supreme Court determined in a 1989 ruling that the commission's investigation and adjudicatory functions under its unitary structure did not pose a due process concern in part because the Supreme Court was the final decision maker. However, the Supreme Court has not been responsible for imposing discipline since a constitutional amendment—which took effect in 1995—gave CJP authority to retire, remove, or censure a judge without the involvement of the Supreme Court.

Since then, the Supreme Court has served a different role in the State's judicial discipline framework: it can choose to review petitions from judges who request reviews of CJP's disciplinary decisions. This role, which is similar to that of an appellate court, is a function the American Bar Association model rules do not include. Even if California adopted a bicameral structure for CJP, we believe that the Supreme Court's current role is effective and should not be changed.

Figure 12

Under the Bicameral Structure, the Disciplinary Body Is Not Privy to Unproven Allegations

Source: Analysis of judicial best practices displayed through a hypothetical example.

CJP's Reliance on Judges to Hear Cases Involving Their Peers Falls Short of the Intent of Proposition 190

Findings of Fact

and Conclusions of Law

Findings of Fact: Determinations about the facts of a case, including witness credibility determinations. CJP's findings of fact must be supported by clear and convincing evidence.

Conclusions of Law: Determinations setting forth the legal basis for CJP's decisions regarding a violation of the ethics code and the associated level of misconduct.

Source: California courts, American Bar Association glossaries, a court case, and CJP decisions.

Structuring CJP as a bicameral commission would also allow CJP to more fully realize the intent of Proposition 190, which California's voters passed to increase the public's involvement with judicial discipline. Although the commission can hear cases in formal proceedings, CJP relies on an independent panel of three judges—known as special masters—to preside over an important portion of formal proceedings: the evidentiary hearing. Figure 13 summarizes the special masters' role in this hearing. Following the conclusion of an evidentiary hearing, the special masters must prepare a report of proposed findings and conclusions, along with an analysis of the evidence and the reasons for their findings and conclusions. The text box further defines these terms. The special masters' report does not comment on the discipline that the commission should issue.

The Commission Rarely Alters the Special Masters' Findings, but It Often Reaches Different Conclusions Based on Those Findings

At the conclusion of an evidentiary hearing, the special masters submit their report to the commission, which can disregard the special masters' report and may prepare its own findings and conclusions. However, the commission rarely altered the findings of the special masters in the cases we reviewed. From fiscal years 2013–14 through 2017–18, CJP accepted the special masters' findings for four of the five cases that completed formal proceedings. Supreme Court decisions have guided the commission's approach to adopting the special masters' findings. When the Supreme Court was responsible for making disciplinary decisions, it gave the special masters' findings special weight because the masters had the advantage of observing the demeanor of the witnesses and were therefore better able to determine the credibility of witnesses. The commission has continued this practice since it became responsible for making disciplinary decisions.

This special weight can influence the commission's decisions about discipline and may have contributed to a judge receiving a lesser form of discipline in one case we reviewed. In this case, a critical finding related to the credibility of the accused judge's testimony. In their final report, the special masters reached the finding that insufficient evidence existed that the judge had acted in bad faith or for a corrupt purpose when he ordered the release of an arrestee whom he knew personally. In the final disciplinary decision, the commission commented that based on their review of the transcript of the judge's testimony, they found it difficult to agree with the special masters' finding. Nevertheless, the commission deferred to the special masters' finding and consequently did not conclude that the judge engaged in willful misconduct, which is conduct committed in bad faith and the most severe form of misconduct. Instead, the commission found that the judge engaged in prejudicial misconduct, which is a less serious level of misconduct. The commission issued a decision of severe public censure—a less serious form of discipline than removal—and specifically commented that the finding that the judge acted in good faith was a factor that influenced its disciplinary decision.

Figure 13

CJP Relies on Special Masters to Make Rulings on the Admissibility of Evidence and to Determine the Credibility of Witnesses

Source: Analysis of CJP's rules, trial counsel manual, and new member orientation documentation.

In contrast, the commission gives less deference to the special masters' conclusions than it does to their findings. This practice continues the approach taken by the Supreme Court when it was responsible for disciplinary decision making. The commissioners adopted the special masters' conclusions for 40 out of the 50 instances of misconduct in the five cases that completed formal proceedings from fiscal years 2013–14 through 2017–18. However, in one case, the commission adopted the special masters' conclusions for 31 out of the 32 instances of misconduct—an unusually high number of instances of misconduct in a single case. Excluding this case, the commission adopted the conclusions of the special masters for nine of the remaining 18 conclusions. In all nine instances in which the commission did not adopt the special masters' conclusions, the commission concluded that the judges in question had engaged in a more serious level of misconduct than the special masters had concluded.

The commission's disagreements with the special masters on the findings and conclusions have been the reason for some judges' petitions for review to the Supreme Court. Two of the five judges who completed formal proceedings with CJP during the five years we reviewed filed petitions for review by the Supreme Court. In one case, one of the reasons that the judge petitioned the Supreme Court for a review was the judge's belief that the commission ignored a critical finding by the special masters. The judge argued that because it ignored this finding, the commission concluded that he had engaged in more serious misconduct and therefore removed him from the bench. In the second case, a judge argued that the commission reached incorrect conclusions because it determined that he had engaged in more instances of and more severe misconduct than the special masters had found. The judge argued that the commission had a pattern of harsher rulings against judges than the special masters. Ultimately, the Supreme Court denied both petitions and left CJP's disciplinary decisions intact. However, as long as the commission does not directly hear cases, judges will likely continue to use differences between the special masters' findings and conclusions and those of the commission to challenge the commission's decisions.

Reforms Resulting From Proposition 190

- Increased the number of commissioners from nine to 11.

- Created a public majority by increasing the number of public commissioners—non-judge, non-attorney members—to six.

- Made public all formal proceedings instituted after February 28, 1995.

- Shifted the authority to retire, censure, and remove judges from the Supreme Court to CJP.

- Shifted the authority to make rules from the Judicial Council of California to CJP.

Source: Proposition 190, passed in 1994.

Moreover, because CJP's rules require the special masters to be judges or retired judges, the special masters oversee proceedings related to the conduct of their peers. This scenario falls short of the intent of Proposition 190 passed in 1994, which sought to heighten transparency and increase the public's role in judicial discipline through the reforms listed in the text box. Supporters of the proposition argued that its changes to CJP's composition would "ensure public control of judicial discipline" and "would eliminate judicial domination of CJP in favor of a public majority."6

However, since the passage of Proposition 190, CJP has never heard its cases and has continued to exclusively use the special masters to hear evidence and assess the credibility of witnesses. The practice of using specially appointed fact-finders is not unusual in other proceedings similar to CJP's formal proceedings. However, in CJP's case, the special masters are overseeing proceedings related to their peers. This leaves judges with a significant amount of influence over judicial discipline—which may impact the control that voters wanted to place in the hands of the public. As we note earlier, when the commission and the special masters disagreed during the period we reviewed, the commission always chose to elevate the level of misconduct. This fact indicates that in these cases, the special masters tended to be more lenient when making determinations about their peers.

Eliminating CJP's Use of Special Masters Would Better Align Its Processes With Best Practices

If the commission began hearing cases, CJP would better align its disciplinary processes with best practices. As we describe earlier, the American Bar Association model rules suggest that judicial discipline commissions adopt a bicameral structure, with one body focused on investigations and the other on discipline. The model rules further suggest that the discipline body should generally hear its own cases and delegate this function to a third-party only when hearing a case would be burdensome to the disciplinary body. Although the commission currently has the option to preside over the evidentiary hearings, it has never done so. In fact, CJP has not developed a full set of rules for how the commission would preside over evidentiary hearings, despite having rules to govern how the special masters must do so. For example, as Figure 13 shows, CJP's current process requires both trial counsel and the judge's attorney to submit proposed findings and conclusions to the special masters, who then file a report with the commission. The commission then considers the entire record and determines the level of discipline.

However, CJP's rules do not describe the steps at the end of an evidentiary hearing if the commissioners hear the evidence directly. Specifically, although CJP's rules allow for a subset of commissioners to preside over an evidentiary hearing, the rules do not address how those commissioners would report to the rest of the commission about the results of the hearing. Therefore, it is not clear how a judge would have the opportunity to review the conclusions from the hearing before the commission determines a level of discipline. Judges currently have this opportunity when the special masters preside over the hearing. This gap in the rules makes it less likely that the commission would ever appoint a subset of commissioners to hear a case directly.

According to the legal advisor who worked for the commission during the majority of this audit (legal advisor), the commission has never heard cases for two reasons: due process and logistics.7 The legal advisor stated that the special masters provide a layer of due process protection because they help separate CJP's investigation function from its determinations about discipline. Her observation has some merit under the current unitary structure, although the commission is privy to unproven allegations and still makes the final decision about discipline. As we discuss previously, a bicameral structure would separate the commission's investigative and disciplinary responsibilities.

The legal advisor informed us that the special masters are also in a better position than the commission to spend the time hearing cases, which can take from a few days to over a week to complete. The commissioners are unpaid volunteers, whereas the legal advisor explained that the special masters are paid by their respective courts while hearing evidence during CJP proceedings. Additionally, the legal advisor expressed concern that if the commission heard cases, it might add to the expense of the hearings because CJP would have to pay for the commissioners' transportation and lodging. However, we believe that these challenges are not insurmountable.

Although hearing cases directly would place new requirements on the commissioners, the State has options for mitigating concerns about these increased expectations. First, it could compensate commissioners who serve on the disciplinary body for the time they spend hearing cases. When CJP initiates formal proceedings, its rules provide judges multiple opportunities to respond and access the evidence that CJP collects. As a result, based on our review of the five completed formal proceedings from fiscal years 2013–14 through 2017–18, the length of time from the notice of formal proceedings to the final decision can be almost a year. If commissioners heard cases directly, they would need to work for specified periods throughout this yearlong process. CJP would also need to ensure that at least one judge or attorney member of the commission participated in the evidentiary hearing to best ensure that it can enforce evidentiary standards.

However, even given these parameters, we do not anticipate that compensating commissioners for the time they spend on formal proceedings would be a large expense. Assuming that the commissioners would spend about 200 hours working on a case—which is the number of hours that the legal advisor estimated the special masters currently spend preparing for formal proceedings, plus the average amount of time that formal proceedings last—we estimate that each case would cost $17,000 per commissioner. Thus, if three commissioners heard the case, formal proceedings would cost approximately $51,000. This estimation assumes that the State would compensate all commissioners at a rate similar to the salary CJP pays its highest compensated staff attorney. This added cost would not be a significant burden considering that CJP completed an average of one formal proceeding annually during our review period. Another option is that CJP could specify that a rotating subset of commissioners would hear formal proceedings. This option would reduce the time commitment that any one commissioner would need to make.

CJP Lacks Clear Authority to Require Corrective Actions That Might Reduce Judicial Misconduct

Unlike comparable entities, CJP does not have express authority to require corrective actions as part of its disciplinary decisions. Although the legal advisor told us that CJP has recommended judges take corrective action—specifically, participating in a pilot mentoring program—its rules provide it with limited options for employing additional corrective actions. Further, the portions of the California Constitution that establish CJP do not expressly provide CJP with the option to require corrective actions. For instance, the legal advisor stated that CJP has no authority to require that judges take educational classes on judicial ethics, even though it considers participation in these types of classes a mitigating factor when it determines discipline.

CJP recently began operating, on a pilot basis, a mentoring program that seeks to foster changed behavior of judges who have been accused of poor demeanor through guidance from trained mentor judges. CJP can offer the program to judges at the completion of its investigations, but judges must agree to participate and participation is currently limited to Northern California. The director stated that as of February 2019, one judge had completed the program and three other judges were enrolled. He further stated that if a judge successfully completes the program, CJP will take that judge's participation into consideration when determining the disposition of the case. According to the director, CJP approved expanding the program to Southern California in March 2018, and it is in the process of selecting mentors and setting up the program in that part of the state. Further, the director anticipates that CJP will make the program permanent by the beginning of next fall once it covers the entire State.

If CJP had the express authority to impose corrective action requirements when it issues discipline, it would have additional options to address judicial misconduct. According to the legal advisor, CJP would benefit from having more corrective action options, such as therapy, anger management, ethics classes, and substance abuse treatment. The chair of the commission also said that corrective actions would be useful in helping CJP advance its mission to protect the public. CJP's director indicated that corrective actions could be a positive addition to the commission's authority. However, he explained that having an investigating attorney both monitor a corrective action and later recommend discipline for failure to comply with a corrective action might cause due process concerns. If the commission were bicameral, it could address this issue. Under the bicameral structure, the investigative body would recommend the corrective action, along with discipline, to the disciplinary body, and the disciplinary body would decide whether to impose the corrective action. A CJP staff member who was not a part of the original investigation could monitor the corrective action to address any potential due process concerns.

Comparable entities, including 18 judicial discipline commissions from other states, the State Bar of California (State Bar), and the Medical Board of California (Medical Board), have the authority to use corrective actions in conjunction with discipline to reinforce positive behaviors in those whom they oversee.8 For example, in addition to disciplining attorneys, the State Bar can require additional conditions, such as educational or rehabilitative work regarding law, ethics, or law office management. Similarly, the Medical Board can require licensed doctors placed on probation to participate in additional professional training and to pass an examination upon completion of the training. To enable CJP to better meet its mission of protecting the public, enforcing rigorous standards of judicial conduct, and maintaining public confidence in the integrity and independence of the judiciary, the California Constitution could provide it with express authority to issue corrective actions along with discipline. This change would strengthen CJP's ability to prevent judicial misconduct from reoccurring.

Reforming CJP's Structure and Operations Would Require an Amendment to the California Constitution

Since its inception, statewide ballot propositions and Supreme Court decisions have incrementally changed CJP's composition, authority, and disciplinary options. For example, when it was first established, CJP had nine members, and the majority were judges. Further, at the time, CJP could not remove or retire a judge; rather, CJP could only recommend that the Supreme Court remove or retire a judge. As we discuss earlier, effective in 1995, Proposition 190 expanded CJP's membership to 11 members, changed its composition to a citizen majority, and allowed it to retire, remove, or censure a judge without Supreme Court approval.

The voters passed the last constitutional amendment that significantly changed CJP's structure and operations in 1994. Our review—the first of its kind and conducted nearly 25 years since the last major constitutional amendment—found that CJP's structure and process require significant reforms for CJP to optimally meet its mission to protect the public, enforce rigorous standards of judicial conduct, and maintain public confidence in the integrity and independence of the judicial system. In this chapter, we have detailed the changes necessary to more closely align CJP's structure and operations with best practices, ensure that its processes better meet the intent of California voters, and provide it with additional options for addressing judicial misconduct.

Because these changes are significant and because much of the foundational criteria for CJP's structure and operations rest in the California Constitution, the implementation of our recommendations would require an amendment to the California Constitution. To this end, the Legislature could propose a constitutional amendment as we depict in Figure 14. The passage of this amendment would require a majority of California's voters to agree to change CJP's structure, require the commission to hear cases, and explicitly authorize CJP to use corrective actions to address misconduct. The amendment would also need to address adding commissioners to ensure that each body has an odd number of members, which is important for voting purposes. Additionally, to hear its own cases without engaging in prejudicial activity the disciplinary body will need to be able to reserve at least three members for formal proceedings. Although we recognize that these changes are substantial, we believe they are necessary to ensure that CJP is positioned to effectively protect both the judges' rights to due process and the public.

Figure 14

Reforming CJP's Structure Will Require a Constitutional Amendment

Source: California State Auditor's recommendations.

* To hear its own cases without engaging in prejudicial activity, the disciplinary body would need to reserve at least three commissioners who did not participate in issuing the notice of intended discipline so that those commissioners could make disciplinary decisions at the end of formal proceedings.

Recommendations

The Legislature should propose and submit to voters an amendment to the California Constitution to accomplish the following:

- Establish a bicameral structure for the commission that includes an investigative and a disciplinary body. The proposed amendment should also require that members of the public are the majority in both bodies and that there is an odd number of members in each body.

- Require that the disciplinary body directly hear all cases that go to formal proceedings and that CJP make rules to avoid prejudicial activity when it hears these cases. The amendment should also require that a majority of the commissioners who hear cases be members of the public and should establish that the State will compensate commissioners for their time preparing for and hearing cases.

- Direct CJP to make rules for the implementation of corrective actions. Establish that such actions are discipline that should be authorized by the disciplinary body and that CJP should monitor whether judges complete the corrective actions.

Chapter 3

CJP Has Not Taken Critical Steps to Improve Its Transparency and Modernize Its Operations

Chapter Summary

In light of the public criticism that it has received over many years and of the value that greater public awareness could provide to its mission, we would expect CJP to have recognized the importance of informing the public about its role and operations. However, it has not taken sufficient action to increase its accessibility or transparency. For example, it has not engaged in outreach campaigns to the general public to promote its mission, provided clear information about its complaint process on its website, or accepted complaints electronically. Further, unlike many state entities, it has not held meetings that are open to the public to discuss its rulemaking, even though its rules are foundational to its operations. Moreover, CJP has not taken critical steps to modernize its operations, such as replacing its antiquated case management system.

Although both modernization efforts and the other improvements we recommend throughout this report will require additional funding, we have identified $504,000 in budget efficiencies that, if realized, could allow CJP to maximize the resources available for its core functions of intake, investigations, and formal proceedings. In addition, to implement the improvements we have suggested, we estimate that CJP will need a one-time budget allocation of $419,000. If it addresses our concerns about accessibility and transparency, CJP may find that it needs additional, ongoing resources to address an increased workload, and it should report regularly to the Legislature about these potential needs.

CJP's Lack of Transparency and Accessibility to the General Public Diminishes Its Ability to Enhance Public Trust in the Judiciary

CJP has not pursued changes to its operations that would bolster public accessibility and transparency while still adhering to its confidentiality obligations. This inaction is true despite the distrust that some in the general public have expressed about CJP for more than thirty years, as we discuss in the Introduction. In light of these criticisms, we believe CJP should have attempted to make itself more accessible and transparent when possible. Such changes include establishing a public outreach campaign, improving the availability of information on its website, accepting electronic complaints, and holding meetings open to the public when appropriate. Although CJP's confidentiality policies limit its ability to share some information with the public, opportunities exist for CJP to increase public transparency and accessibility, thereby improving the public's trust in the judiciary.

CJP Has Performed Only Limited Public Outreach

CJP has not made an adequate effort to ensure that members of the general public know of its existence, or of the role it plays in the judicial system. According to its list of outreach events, CJP participated in an average of 25 meetings and presentations annually from fiscal year 2013–14 through 2017–18. However, these meetings usually involved court employees and legal professionals, and they generally did not include opportunities for members of the general public to learn about CJP's role, mission, or processes. For example, of the 21 events during fiscal year 2017–18 that CJP participated in, 16 events were aimed at legal professionals and one was a conference for people who regularly work in or interact with courts, such as social workers and probation officers. The remaining outreach events were for law schools and groups with an international focus, such as an international visitor leadership program. According to the chair, commissioners sometimes speak about CJP on their own to organizations such as local rotary clubs. However, none of the events in which CJP formally participated during the 2017–18 fiscal year targeted the general public. In fact, in the five fiscal years we reviewed, CJP participated in only three events that targeted the general public out of more than 120 events total over that period.

Additionally, CJP depends on courts' cooperation if it wants to publicize its existence in courthouses. CJP's legal advisor explained that CJP has no authority to require courts to post or display information about CJP or the process for filing complaints, although CJP's supervising administrative specialist told us that CJP has provided brochures to a few courts that requested the information. Because the State does not require courts to post information about CJP in prominent locations within each courthouse, a significant gap exists in the accountability of the judicial system. Those who are most likely to observe judicial misconduct—such as court staff, jurors, and litigants—can generally be found in the State's courthouses.

A requirement that courthouses post information about CJP in prominent locations would not be unprecedented. For example, one option for doctors to meet the Medical Board's public notice requirements is to prominently post a notice with the Medical Board's contact information in an area that is visible to patients. If the Legislature amended state law to compel courts to comply with similar notification requirements, information about what CJP does and how to contact it would be readily accessible in courts. The presence of this information would better ensure that court staff and members of the public who interact with judges are aware of how to file complaints regarding judicial misconduct.

CJP Has Not Ensured That Its Website Clearly Presents Sufficient Information About the Complaint Process

CJP's website does not provide adequate guidance about how to submit complaints that include sufficient information for it to initiate an investigation. We found that when individuals who were not attorneys submitted complaints, CJP was nearly 50 percent more likely to close the complaints without performing an investigation, compared to when attorneys submitted them. Factors such as the attorneys' legal training and the frequency with which they interact with judges could explain why CJP investigates their complaints more frequently. However, the fact that so many of the complaints submitted by members of the general public lack merit may indicate that CJP could do more to educate the public about its processes and requirements.