Use the following links to jump directly to the section you would like to view:

- The County's Failure to Actively Monitor Its Lease With the Association

Resulted in the Loss of Significant Revenue - The Association’s Executives Receive Much Higher Compensation Than Executives

That Run Other Large Fairs in California - The Association Operated an RV Park With Numerous Safety Violations

- Other Areas We Reviewed

- Scope and Methodology

The Ground Lease and Operating Agreement’s Definition of Gross Revenues

The Ground Lease and Operating Agreement (lease) defines gross revenues to encompass any and all money and cash receipts—without deduction for any overhead, cost or expense of operation—received by the association from use of the Fairplex, including but not limited to the following:

- Admissions.

- Gross charges.

- Sales.

- Rentals.

- Fees.

- Commissions.

- In-kind payments, assets, property or other things of value, made or received in lieu thereof.

The lease excludes the following from its definition of gross revenues:

- Governmental grants for specific purposes.

- Taxes collected by the Los Angeles County Fair Association (association) for the benefit of a governmental body.

- Advertising or promotional considerations related to the operation of the fair.

The association must annually pay Los Angeles County (county) a percentage of the gross revenues it receives from its use of the Fairplex.

Source: The 1988 lease between the county and the association.

The County's Failure to Actively Monitor Its Lease With the Association Resulted in the Loss of Significant Revenue

Key Points:

- The county’s expectations of how much revenue the association would pay it in rent based on the operations of the association’s hotel have changed considerably over time, and the county cannot adequately explain the timing or reasoning behind its decisions to lower its expectations. Had the county insisted that the association pay it rent as specified in the terms of the lease, the county would have received an additional $6.2 million related to the hotel for the years 2006 through 2015 alone.

- The county has not ensured that the association paid it rent from the conference center, as the association represented it would when it asked the county for financial help with the conference center’s construction costs. As a result, we estimate the county has failed to collect an additional $350,000 in rent since 2012.

- The county does not collect rent on the millions of dollars that the association’s subsidiaries earn at the Fairplex.

For Reasons It Cannot Fully Explain, the County Essentially Relinquished More Than $6 Million in Rent Due From the Hotel’s Operations

The county failed to actively monitor its lease with the association, potentially resulting in a loss of more than $6 million in rent revenue related to the hotel alone during our 10-year audit period. As Figure 4 illustrates, the county entered into its current lease with the association in 1988 in part to enable the association to develop the Fairplex by constructing the hotel and other projects. The terms of the lease state that the association must annually pay the county a percentage of the gross revenue it receives from its use of the Fairplex. As the text box shows, while the lease explicitly omits certain limited revenue categories from the rent calculation, the definition of gross revenues includes revenue the association receives as a result of its own business activities, as well as any money the association receives from other activities on Fairplex property.

Figure 4

Timeline of the Understanding of Rent to Be Paid to Los Angeles County From Operations of the Los Angeles County Fair Association’s Hotel and Conference Center

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of county records, the association’s audited financial statements, the association’s 1997 hotel management agreement, the association’s 2004 hotel management agreement and 2009 amendment, and interviews with county and association staff.

Revenue earned by the hotel—which the association opened in 1992 and which is currently known as the Sheraton Fairplex Hotel—falls under the lease’s definition of gross revenues because the hotel is not a separate legal entity, but rather an asset owned by the association, a fact that the county appears to have understood around the time it entered into the lease. Specifically, in June 1990, as the association was in the planning phase of building its hotel, an assistant administrative officer with the county indicated in a letter to a county supervisor that the county would receive a percentage of the hotel’s gross revenue. Additionally, in 1992 the same assistant administrative officer with the county sent a letter to a state agency that suggested the county expected the association to pay it a percentage of gross revenue generated from the hotel.

The terms of the lease related to the calculation of rent have remained unchanged since 1988, with the exception of certain assistance the county has agreed to provide to the association, as we discuss later in the report. Nonetheless, the county’s expectations of how much rent it would collect from the hotel’s operations each year have changed considerably over time, to the county’s detriment. Specifically, we estimate that the association could have owed the county an additional $6.2 million in rent from 2006 through 2015 alone based on the gross revenue from the operations of the association’s hotel. Rather than collecting this amount, however, the county appears to have agreed that the revenue earned by the hotel did not meet the definition of gross revenues for reasons that it cannot adequately explain and that it did not adequately document. Instead, it allowed the association to include only fees and other payments it received from the hotel in its rent calculation. According to the association, it has never included any gross revenues generated by its hotel in its rent calculation. Table 4 shows the rents as calculated by the association, as well as additional rents we calculate that it should have owed, based on the lease. Table 4 also includes $350,000 from the operations of the association’s conference center, which opened in 2012. We discuss issues related to the conference center later in this report.

This understanding severely limited the amount of rent the association owed the county related to the hotel’s revenue. According to the association, it entered into an agreement with an outside party to manage its hotel in June 1991. Although the association was unable to provide the original agreement, a 1997 letter that the association sent to the county stated that the hotel management agreement required the hotel to pay the association $50,000 per year in basic fees and another $133,000 in additional fees. According to the understanding the county apparently reached with the association, the association would then pay a percentage only of this $183,000 as rent, rather than a percentage of the hotel’s gross revenue. We find this arrangement problematic, given that the hotel is not a legally separate entity and is part of the association itself. Further, if the county had determined that it was in its own best interest to collect a percentage only of these fees, we find it concerning that the county did not maintain adequate documentation to explain and support its reasoning.

| Year | Rent Due* | Less Rent Credit† | Actual Rent Paid | Potential Additional Rent Based on Los Angeles County Fair Association’s Hotel and Conference Center’s Operations‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $961,819 | - | $961,819 | $453,810 | |

| 1,003,211 | - | 1,003,211 | 489,010 | |

| 1,201,648 | $(800,000) | 401,648 | 673,382 | |

| 998,898 | (800,000) | 198,898 | 493,409 | |

| 937,796 | (800,000) | 137,796 | 516,844 | |

| 869,057 | (800,000) | 69,057 | 600,639 | |

| 894,996 | (800,000) | 94,996 | 724,418 | |

| 955,941 | (800,000) | 155,941 | 804,815 | |

| 1,149,028 | (800,000) | 349,028 | 888,255 | |

| 1,062,002 | (800,000) | 262,002 | 867,945 |

Sources: Los Angeles County’s (county) financial documents, the California State Auditor’s analysis of the Los Angeles County Fair Association’s (association) audited financial statements, and the Ground Lease and Operating Agreement (lease) between the county and the association as amended.

* The association calculates its rent based on a percentage of revenue it receives at the Fairplex. The association did not include rent related to its Sheraton Fairplex Hotel and Conference Center’s operations in its calculation during the years identified. This column does not include any subsequent adjustments for overpayment or underpayment resulting from ensuing rent calculation reviews. The subsequent adjustments were minor and did not exceed a net total of $15,000 in any lease year.

† The county provided the association with an annual credit of $800,000 against its rent due to the county since 2008 to support the association’s financing of the development and construction of a conference center at the Fairplex. This rent credit will continue until 2022.

‡ The dollar amounts shown for the years 2006 through 2011 only include rent related to the hotel’s gross revenue. For the years 2012 through 2015, gross revenue includes activities related not only to the hotel, but also to the conference center, which opened in 2012. Based on year‑by‑year projections the association provided to the county, we estimate that roughly $350,000 of the total shown for the years 2012 through 2015 related to the conference center’s operations. Consequently, we estimate that the county relinquished a total of $6,162,527 from 2006 through 2015 by allowing the association to exclude its hotel’s gross revenue from its rent calculation.

Moreover, in 1997 the association entered into a new hotel management agreement with a different hotel operator that further reduced the rent it owed the county. Specifically, the 1997 hotel management agreement fixed the annual fee that the hotel must pay the association at $50,000, the fee amount that is still in effect. Consequently, the fee amount was reduced from $183,000 to $50,000. Adjusting for inflation, the association could hypothetically now owe the county less annually from the hotel’s operations today than it did in 1992, when the hotel first opened.

Current county staff was unaware that the terms of the 1991 hotel management agreement changed in 1997 and reduced the hotel fees until we brought the issue to their attention. The lease requires the association to seek the county’s approval for all subleases that exceed 10 years and also gives the county the right to request any of the association’s subleases and other information relating to a proposed subtenant’s identity, nature of business, and financial responsibilities. However, the association’s hotel operating or management agreements are not considered subleases, and therefore this requirement does not apply. Although the association benefits by treating the hotel as a separate entity when calculating its rent, it does not have a sublease with the hotel because the hotel is one of its business activities. Therefore, the association does not have to obtain the county’s approval before executing such agreements.

The amount of rent the association owed the county was also limited by the subordination of the hotel fees to payments on the debt that the association had incurred to finance the construction of the hotel. Specifically, in 1997 the association refinanced the debt it had incurred to build the hotel. As a condition of refinancing this debt, the association’s lender required the county to recognize that any rent due to it from the hotel’s operations was subordinate to the association’s debt service on the hotel. In other words, the association would not owe the county even minimal rent from its hotel’s operations until the subordination provisions of the bond documents were satisfied.

In connection with the debt refinancing, the county’s Chief Executive Office confirmed the county’s acquiescence to this subordination arrangement, though the county was not clear regarding whether it believed it would eventually receive rent based on the hotel’s gross revenue or based on a percentage of the fees that the hotel transferred to the association. In a letter dated February 1997, in response to a request by the association, the county confirmed that it did not expect to receive rent related to the hotel until the subordination provisions of the bond documents were satisfied. However, the county also stated that pursuant to the lease, the association was required “to pay, as rent to the County, specified percentages of gross revenues from the Fair and gross receipts from Interim Events. The rent from Interim Events at the Fairgrounds includes the development and operation of the hotel.” It further stated that “it is the County’s expectation that the unpaid required land rent on the hotel has been accruing, and that the County will receive all current and back due Interim Rents from the hotel development when the subordination provisions have been satisfied.” The language used in this letter is inconsistent with the terms that define the rent calculation in the lease, and therefore does not clearly indicate whether the county still expected that it would eventually receive a percentage of the hotel’s gross revenue upon satisfaction of the subordination provisions.

The association’s subsequent actions and the county’s poor management of the lease resulted in the continued delay of the association’s payment of the back rent it owes, which the county will not receive until 2039 under the current situation. Although the county was aware of the association’s 1997 refinancing of its debt, the association subsequently refinanced its debt multiple times without explicitly informing the county or seeking its approval. According to the county’s deputy compliance officer, the county was unaware of the association’s further debt refinancings in 2000 and 2009. Although the county should have learned about the association’s refinancing of the debt when it reviewed the financial statements that the association generally provided to it on an annual basis, it appears the county did not observe that the refinancing had occurred. According to the association, it has never paid rent to the county based on the hotel’s fees. This assertion aligns with our finding that the association excluded its hotel’s annual fees from the rent calculation for our audit period from 2006 through 2015.

Although the county was aware of the association’s 1997 refinancing of its debt, the county was unaware that the association subsequently refinanced its debt multiple times.

The county’s deputy compliance officer stated that when the county agreed to the original debt refinancing in 1997, it did not anticipate that the association would continually refinance its debt. The county’s legal counsel also stated that the 1997 letter related to the bond issuance in that same year did not contemplate future refinancing; therefore, he believed the association should have obtained further consent from the county when it subsequently refinanced the debt. He also stated that the county did not ensure compliance in this area because it was unaware of the association’s actions until after the association had already refinanced its debt. According to the terms of the lease, the association is not required to give notice to the county when it refinances its debt. As it is, the association will be making payments on its debt through 2039, which is only four years before the lease term expires in 2043. Therefore, the county may not receive any rent related to the hotel’s operations until near the end of the lease term.

In 2006 the county further exacerbated the problems created by its weak management of the lease when it apparently allowed the association to exclude its hotel’s gross revenue from its rent calculation, and instead include only hotel fees and any other payments the association receives from the hotel. The county had contracted with an outside party to perform a review of the rent paid to the county by the association for the year ended December 31, 2004.1 The reviewer’s final report in June 2006 noted that the exclusion of the hotel’s revenue from the rent calculation was consistent with previous years. However, the reviewer noted that the treatment of hotel revenue is unclear in the lease and that the county should issue a clarifying statement on the matter. Further, the reviewer stated that it was the opinion of the county that the association properly excluded the gross revenue earned by the hotel when preparing the rent calculation. Based on the definition of gross revenues in the lease, we do not understand how the county reached this conclusion, and the county could not provide a reasonable explanation as to why it agreed to this treatment. In response to the reviewer’s recommendation, the county issued a letter in September 2006 that stated in part that revenue earned by the hotel did not meet the definition of gross revenues but that fees and other payments received by the association from the hotel are included in its rent calculation.

Because the hotel is one of the association’s business activities, the association effectively received the hotel’s revenue and thus should have been paying rent based on that revenue under the terms of the lease. When we questioned the association, it stated that the county has benefited from development of the hotel and the conference center we describe later in numerous ways. According to the association, these facilities not only substantially increased the value of the county’s property, but also helped bring numerous conferences and events to the Fairplex, and with them, visitors and spending in the region. However, we found little evidence that the county had made an informed decision about excluding the hotel’s revenue based on these possible benefits.

Under the terms of the lease, the association should have been paying rent based on the hotel’s revenue.

By not monitoring the lease, the county very likely relinquished approximately $6.2 million in rent from 2006 through 2015. Instead, under the current arrangement, we calculated that the county is due only approximately $70,000 in arrears in total rent related to the hotel fees since 1992.

Despite Providing the Association With $12 Million in Rent Credits, the County Has Yet to Collect Rent Related to the Conference Center’s Operations

Although the county expected to receive additional rent from the conference center the association built in part with assistance in the form of rent credits from the county, it has actually received no rent related to the conference center’s operations. In 2007, as the association was attempting to obtain funding to help it build a conference center at the Fairplex, its president at the time asked the county to help finance the project and expressed that the county would receive a direct increase in rent from the conference center’s operations and from the growth of complementary businesses on site. Ultimately, the county agreed to provide the association with $12 million in the form of an $800,000 annual credit (rent credit) that the association could apply against its rent due to the county for 15 years. When the county agreed to the rent credit, it indicated that it expected to receive an additional $250,000 annually from the conference center’s operations when the conference center was at full capacity. The county based this amount on the information the association provided to it, which suggested that the county would ultimately receive $150,000 in increased rent revenue and $100,000 in increased taxes.

However, the association subsequently took actions that resulted in it not paying rent to the county based on the conference center’s revenue. Specifically, in 2009 the association amended its hotel management agreement so that its hotel operator would also operate the association’s conference center in addition to operating the association’s hotel. The association stated that it placed the conference center with the hotel’s operations because the types of businesses were similar and many of the conference center’s guests stay at the hotel. As a result, although the conference center opened in 2012, the county has received no additional rent from its operations, despite agreeing to provide the association with $12 million in rent credits. The association’s failure to pay rent related to the conference center appears to directly contradict its representations to the county when it was asking for help with financing the construction.

The county has received no additional rent from the conference center’s operations, despite agreeing to provide the association with $12 million in rent credits to help finance the project.

Based on year-by-year projections the association provided to the county three months before the county approved the rent credit, we estimate that the county has lost out on roughly $350,000 in total rent revenue related to the conference center since it opened in 2012. According to the county’s deputy compliance officer, the county never agreed to the exclusion of the conference center’s revenue from the association’s rent calculation, and it only recently discovered that it was not receiving rent from the conference center’s activities. The county’s auditor-controller uncovered this issue in early 2016 during the county’s review of the association’s rent calculation for the years 2012 through 2014. This review occurred four years after the conference center opened and seven years after the association amended its hotel management agreement to also include management of the conference center.

Reviews of the Los Angeles County

Fair Association’s Rent Calculations

for the Years 2006 Through 2014

Year(s) Reviewed

(Report Release Date)

2006

(December 2007)

2007 to 2011

(July 2014)

2012 to 2014

(Projected November 2016)

Source: Los Angeles County records.

Had the county conducted timely reviews of the association’s rent calculations, it likely would have uncovered this problem more quickly. Although the county or its contractor has conducted periodic reviews of the association’s rent calculations that cover every year from at least 2006 through 2014, it has not always conducted these reviews in a timely manner. For example, as shown in the text box, at one point the county went longer than six years without conducting a review even though its informal goal was to conduct these reviews every three years. Although it then conducted a review that covered the previous five years, such long gaps between reviews could allow the association to improperly calculate the rent it owes the county for extended periods of time. As described above, the association excluded the conference center’s revenue from its rent calculation for the four years following its opening. Had the county adhered to its goal to review the association’s rent calculation every three years, it would have conducted reviews in 2010 and 2013. Because the 2013 review would have included the year in which the conference center began operations, the county likely would have discovered the association’s exclusion of the conference center’s revenue much earlier and been able to resolve the problem in a more timely manner.

The County Has Not Collected Rent Related to the Gross Revenues of the Association’s Subsidiaries

In addition to the rent the county does not collect related to the association’s hotel and conference center, it also does not collect rent based on the gross revenues of the association’s subsidiaries. As previously discussed, the terms of the lease require the association to pay rent based on revenue it receives from the use of the Fairplex. Under its business structure at the inception of the lease in 1988, the association likely received almost all of the revenue generated from the use of the Fairplex. However, as Figure 2 in the Introduction shows, the association has made significant changes to its business operations since 1988 by creating various for-profit subsidiaries, each of which it wholly controls. Unlike the hotel and conference center, these subsidiaries are legally separate entities. Consequently, the association itself does not directly receive these revenues and, under the terms of the lease, these amounts are not includable in the rent calculation. These revenues totaled roughly $18 million in 2015.

Instead, the association must include in its rent calculation only the amounts its subsidiaries pay in fees to the association, as seen in Figure 5. However, because the association controls its subsidiaries, the amount of rent it pays to the county is driven by the amount of fees the association decides to charge its subsidiaries. In contrast, the Redevelopment Agency of Pomona had an agreement with the association that included the type of language that could have benefited the county in its lease with the association. In 1990 the association and the Redevelopment Agency entered into an agreement related to the hotel. This agreement entitled the Redevelopment Agency to receive a portion of the net profits generated by all the food and room service operations at the hotel. The agreement specifically applied to all entities “who directly or indirectly derive profits from the hotel’s food and room service operations,” including sublessees. Essentially, this agreement focused on the revenue generated by the use of the land instead of the revenue received by the association. Had the county chosen to use similar language in its lease, the association’s rent would have been based on all of the association’s and its subsidiaries’ Fairplex‑related revenue, regardless of any changes the association made to its business structure.

Figure 5

Structure of the Los Angeles County Fair Association’s Rent Payments to Los Angeles County

Sources: 1988 Ground Lease and Operating Agreement between the association and Los Angeles County (county); the association’s agreements with its hotel and conference center, subsidiaries, and outside parties; the association’s audited financial statements; and county records.

* We define “fees” to mean any amounts the association receives from its hotel and conference center or under the terms of its subleases with its subsidiaries and outside parties for use of the Fairplex.

Further, the county could have benefited by including in the lease the type of renegotiation opportunities that it includes in its other agreements. For example, the county has an agreement with another entity that identifies specific renegotiation dates; on these dates, the annual rent percentages can be readjusted according to the fair market rental value. Because the county’s lease agreement with the association does not include such a renegotiation provision, there was no automatic mechanism in place for the county to adjust the rent calculation as the association’s business structure changed. Although the lease does specify incremental percentage increases in rent over time, it does not give the county the ability to renegotiate these percentages to ensure that it receives rent in an amount that reflects the property’s rental value. The county’s decision to enter into a long‑term lease with no renegotiation provision suggests that it did not foresee that the association’s activities and business structure would change in such a way that large portions of revenue generated at the Fairplex would be excluded from the rent calculation.

However, the county may have an opportunity to amend the lease to collect additional revenue from these subsidiaries, as well as to include language to clarify its share of the hotel’s and conference center’s revenues. Specifically, according to county records, the association has approached the county about a potential amendment to the lease in part because the association is considering additional developments at the Fairplex. In November 2015, the county’s Board of Supervisors directed county staff to continue negotiations for a potential amendment to the lease, with the directive that they should structure any amendments to fully maximize the association’s payments to the county. Because any amendments to the lease require the Board of Supervisors’ approval, the county has leverage in its negotiations with the association and should take advantage of this opportunity to address the problems created, in part, by its weak lease management in the past.

Recommendations

By April 2017, the county should reach agreement with the association on the following issues:

- The date by which the association must pay the county for the rent in arrears related to the hotel.

- How much rent the association owes the county from the hotel’s operations since 1992.

As soon as possible, the county should collect from the association all amounts presently owed under the lease as a result of the revenue generated by the conference center.

To ensure that it recognizes and addresses in a timely manner areas of potential concern related to the association’s rent, the county should create and adhere to a policy of reviewing the association’s rent calculations at least every three years.

To protect its interests and maximize its future revenue, the county should strongly consider ensuring that any potential amendment to the lease includes the following:

- A revised rent calculation formula that factors in revenue from all of the association’s activities, including its hotel and conference center, as well as revenue from its subsidiaries’ activities at the Fairplex. This revised rent calculation formula should require the association either to pay the county an agreed-upon fixed amount, adjusted periodically for inflation, or to pay the county both a fixed amount every year and a percentage of the total gross revenue that the association earns at the Fairplex.

- Terms that define the circumstances or dates that require a renegotiation of the lease and the rent calculation formula.

- An agreement on the types of entities whose gross revenues the association must include in rent calculations. This agreement should cover any new businesses the association creates that operate at the Fairplex.

- Terms that require the association to provide the county with any subleases it wishes to enter, even those subleases that do not exceed 10 years. The terms should also require the association to provide the county with approval over other agreements that could affect the rent calculation, including the association’s hotel management agreement and its amendments.

- Terms that require the association to provide the county with advance notice of any refinancing of the association’s debt and what impact, if any, such transactions would have on the amount or timing of rent payments to the county.

The Association’s Executives Receive Much Higher Compensation Than Executives That Run Other Large Fairs in California

Key Points:

- The association provides its executives with significantly higher compensation than the executives of other large fairs receive.

- The association engaged outside contractors to perform compensation studies that it used to review its executives’ salaries.

Perhaps in part because the county has not collected rent on some of the association’s activities related to the use of the Fairplex, the association has been able to provide its executives with much higher compensation than the executives who are in charge of other large fairs in California have received. As we discuss in the previous section, the county has not received approximately $6.5 million in total rent related to the hotel and conference center from 2006 through 2015. During roughly this same time period, the association consistently paid its then president total compensation greater than half a million dollars annually, according to its federal tax filings. Further, in 2014 it also paid many of its other executives more than the chief executives in charge of other large fairs earned.

During our audit period, the levels of compensation the association provided its executive management team varied as a result of the association’s bonus-based compensation structure. Specifically, from 2006 to 2014, the association’s former president’s compensation ranged from a low of $549,000 in 2009 to a high of $1.2 million in 2007. His 2014 compensation totaled more than $1 million—$547,312 in base compensation, $442,725 in bonus and incentive compensation, and $55,051 in other compensation and benefits. Further, the association paid six of the seven members of its executive management team more than $200,000 in 2014, as shown in Table 5. The seven executives collectively earned a total of $2.9 million in 2014. Moreover, the total reported compensation the association paid to its four highest-paid executives increased from 7 percent of its total salaries and employee benefits in 2006 to 13 percent in 2014.

According to the classification system the CDFA uses, the LA County Fair is one of only five Class VII fairs in the State, which are fairs with average operating revenues of more than $10 million per year. Public entities operate three of these Class VII fairs. Specifically, DAAs operate the Orange County Fair and San Diego County Fair, while a state agency operates the California State Fair. The annual base salary for chief executive officers (CEOs) in charge of Class VII fairs at the two DAAs ranges from $104,988 to $128,808. In addition, these CEOs are also eligible to receive recruitment/retention pay differentials as well as car allowances, which can increase their total compensation. The annual base salary for the CEO in charge of the California State Fair currently ranges from $149,916 to $175,368.

| Title | Base Compensation | Bonus and Incentive Compensation | Retirement and Other Deferred Compensation | Nontaxable Benefits | Total Compensation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| President and chief executive officer | $547,312 | $442,725 | $28,783 | $26,268 | $1,045,088 |

| Vice president of finance and chief financial officer | 244,450 | 176,069 | 28,783 | 5,514 | 454,816 |

| Vice president of operations | 189,191 | 149,586 | 28,783 | 13,463 | 381,023 |

| Vice president of sales, marketing, and programs | 210,901 | 185,586 | 28,783 | 13,204 | 438,474 |

| Vice president of branding and product knowledge | 161,445 | 113,305 | 28,288 | 9,596 | 312,634 |

| Vice president of business management | 179,575 | 21,449 | 5,833 | 19,536 | 226,393 |

| Vice president* | NA | NA | NA | NA | 86,869 |

Source: The Los Angeles County Fair Association’s (association) publicly available 2014 Internal Revenue Service (IRS) tax filing.

* This individual was named to the position in August 2014. Because her reportable compensation—the total of her base compensation and bonus and incentive compensation amounts—was below $150,000, the IRS instructions did not require the association to present a breakdown of her compensation in its IRS tax filing.

On the other hand, nonprofit organizations run the LA County Fair and the Alameda County Fair. Because these nonprofit organizations are corporations, they are not required to implement the same salary ranges that public entities must. Although we did not analyze the process the nonprofit organization that runs the Alameda County Fair uses to set its executive compensation, we noted that it is registered as a charitable organization. A charitable organization is subject to certain federal taxes if its executive compensation is excessive. The association, however, is not a charitable organization—rather, it is an agricultural organization—and thus is not subject to these taxes. The association pays its executives a base salary, plus a bonus for meeting defined performance targets. Such targets may relate to revenue, operating income, and various strategic goals. The association’s approach to determining compensation allowed it to provide its former president much higher compensation than the chief executives in charge of other Class VII fairs received in 2014, as seen in Figure 6. In fact, many of the association’s top executives earned more than the CEOs of the organizations that operate the State’s other Class VII fairs. The same individual served as the association’s CEO throughout our audit period until he resigned in March 2016, and we found that his total reported compensation generally followed the trend of the association’s revenue from 2006 through 2014. By comparison, we note that the San Diego County Fair generated revenue similar to that of the LA County Fair in 2014, yet its CEO received far less in total compensation.

Figure 6

Compensation Amounts in 2014 for Chief Executive Officers or Comparable Positions That Managed Class VII Fairs

Sources: The Los Angeles County Fair Association’s 2014 audited financial statements and Internal Revenue Service Form 990, the Alameda Agricultural Association’s 2014 Form 990, and information provided by the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA).

Note: The CDFA defines Class VII fairs, the largest class of fair in the State, as those fairs with average annual operating revenue of more than $10 million.

* Compensation shown for the nonprofit executives includes base, bonus, and incentive compensation; it does not include retirement, other deferred compensation, or nontaxable benefits. Compensation shown for the executives of public entities includes base compensation and benefits such as recruitment/retention pay differentials and car allowances, as applicable.

† The Los Angeles County Fair Association operates the LA County Fair.

‡ The Alameda Agricultural Fair Association operates the Alameda County Fair.

§ California Exposition and State Fair operates the California State Fair.

II The 32nd District Agricultural Association operates the Orange County Fair.

# The 22nd District Agricultural Association operates the San Diego County Fair.

We acknowledge that the association is legally allowed to set its executive compensation at levels greater than those set by public entities, and we recognize the association’s desire to attract and maintain talent to manage a complex organization. During our audit period, the association commissioned executive compensation studies by two different consulting firms, which they completed in 2008 and 2011. In the studies, the consulting firms reviewed both for-profit and nonprofit organizations in industries such as hotels, recreation, fairs, and trade associations, as well as other market data. The studies found the association’s executive compensation arrangement to be generally reasonable and competitive. According to the association, its executives manage more complex operations than do the executives of many Class VII fairs. For instance, the association stated that it oversees the hotel and conference center and the year-round operations at the Fairplex campus, which is in use throughout the year for hundreds of events large and small. Similarly, the association stated that it oversees various affiliated businesses such as its subsidiaries and its related nonprofit entities. We present some of the differences between the association and the other organizations that operate Class VII fairs in Table 6. Of particular note is that the association has significantly more employees than the other organizations do.

| Organization and Fair | Governmental entity | Nonprofit Organization | Operates a Fair | Number of Employees in 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Los Angeles County Fair Association (Los Angeles County Fair) | ✔ | ✔ | 1,711 | |

| Alameda County Agricultural Fair Association (Alameda County Fair) | ✔ | ✔ | 744 | |

| California Exposition and State Fair (California State Fair) | ✔ | ✔ | 215 | |

| 32nd District Agricultural Association (Orange County Fair) | ✔ | ✔ | 103 | |

| 22nd District Agricultural Association (San Diego County Fair) | ✔ | ✔ | 367 |

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of the Class VII fairs’ publicly available Internal Revenue Service tax filings, financial statements, and websites; California Department of Food and Agriculture records; and state law.

The Association Operated an RV Park With Numerous Safety Violations

Key Points:

- The Redevelopment Agency of Pomona provided the association with $3.3 million in 2009. In exchange, the association agreed to provide affordable housing at one of its RV parks for more than five decades.

- The association allowed conditions at the RV park to deteriorate to such an extent that state inspectors discovered several health and safety violations.

Although the Redevelopment Agency2 provided the association with millions of dollars related to an RV park at the Fairplex, the association failed to maintain the RV park, resulting in it being cited for numerous health and safety violations. In 2009 the Redevelopment Agency provided the association with $3.3 million for the purchase of 50 affordable rental space covenants at the association’s 160-space RV park. The terms of this purchase required the association to make the 50 spaces available for 55 years, or until 2064, to tenants whose income levels are very low to moderate.

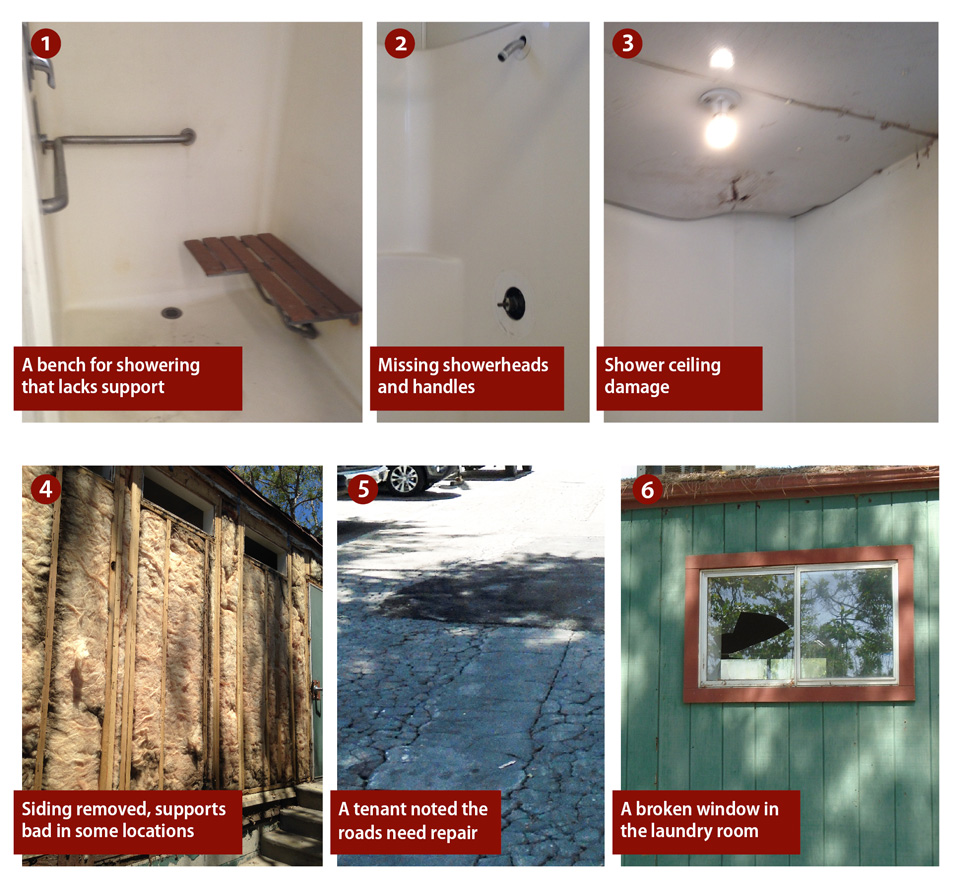

State regulations require the owners of RV parks to safely maintain and operate all common areas; park-owned electrical, gas, and plumbing equipment; and park-owned permanent buildings or structures. Nonetheless, the association did not fully comply with these regulations. Specifically, in February 2015 a resident of the RV park submitted a complaint to HCD, which has enforcement authority over the RV park under state law. The resident reported a lack of handicapped access into restroom or shower buildings, a broken window in the men’s shower, substandard electrical boxes, and excessive potholes in the roads. According to an administrator at HCD, the issues in the resident’s complaint did not include what HCD considers to be immediate threats to the health and safety of the residents—gas leaks, exposed electrical wiring, or sewer leaks—and because the HCD inspectors had a backlog in their workloads, an HCD inspector did not visit the association’s RV park until July 2015.

At her initial inspection of the RV park, the HCD inspector discovered several violations of the California Health and Safety Code, including broken restroom windows, mold, substandard flooring, and other issues, some of which are shown in Figure 7. The inspector also noted that the association had begun repairs to the restrooms without obtaining proper work permits. She ordered the association to cease its repair work and to obtain the required work permits within 10 days.

Figure 7

Photos of Some Issues Noted at a Recreational Vehicle Park the Los Angeles County Fair Association Owns and Operates

Sources: The Department of Housing and Community Development’s activity report for the recreational vehicle park dated July 13, 2015 (photos 1–4), and observations by the California State Auditor on April 27, 2016 (photos 5–6).

At a subsequent inspection in January 2016, two HCD inspectors discovered that the association had been operating the RV park without the necessary permit for 29 years. In 1986 the association began operating a second RV park at the Fairplex. According to the association, it operated the two parks as one business unit with the same business address; consequently, it believed the permit it obtained to operate the association’s second RV park covered both parks. When HCD discovered the problem in January 2016, it ordered the association to apply for the permit within 15 days and to pay about $42,500 in back fees and penalties. The association promptly paid the fees and obtained the permit to operate the RV park.

Further, during a detailed inspection of the RV park in March 2016, an HCD inspector found more serious violations that were determined to be an imminent hazard to the health and safety of RV park residents. Specifically, in several spaces at the RV park, the park’s electrical service equipment had been exposed or had easily accessible live electrical parts. The inspector instructed the association to fix these violations immediately, and the association took immediate steps to comply. HCD determined that the association had fully addressed these violations in May 2016.

However, the association took longer to correct other violations that the HCD inspectors identified during their March 2016 inspection. Specifically, of the 17 violations identified, the association had failed to resolve six—including accumulation of refuse and unapproved plumbing extensions—as of August 2016. As a result, HCD issued the association a notice of intent to suspend its permit to operate, giving the association 30 days to correct the violations. In September 2016 HCD determined that two spaces at the RV park still had an accumulation of refuse or other combustible material and ordered the association to abate the remaining violations or HCD could pursue further administrative measures. HCD conducted a reinspection in October 2016 and determined the RV park was in compliance with the applicable regulations.

Other Areas We Reviewed

To address the audit objectives approved by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee (Audit Committee), we also reviewed the association‘s processes for selecting its members and electing its directors, its hiring and compensation practices, its financial and accounting practices, its nonprofit status, and its involvement in a lawsuit related to the collection of transient occupancy taxes at its RV parks. Table 7 shows the results of our review of these issues.

| The Los Angeles County Fair Association’s Selection of Members and Election of Directors |

|

| The Association’s Hiring and Compensation Policies |

|

| The Association’s Financial and Accounting Practices |

|

| The Association’s Nonprofit Status |

|

| The Association’s Involvement in a Lawsuit Related to Its Collection of Transient Occupancy Taxes |

|

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of the records identified in this table.

Scope and Methodology

The Audit Committee directed the California State Auditor (State Auditor) to review the county’s oversight of the association. Table 8 lists the objectives that the Audit Committee approved and the methods we used to address them. As a private entity, the association is not under the same legal obligation to provide documentation or other information to the State Auditor as publicly created entities are. Nonetheless, we requested and received documents from the association in order to address certain audit objectives, such as its executive compensation studies, hiring policies, financial statements, bylaws, board minutes, hotel management agreements, and subleases. In addition, association staff met with members of the audit team to provide current and historical information on the association’s operations. However, we agreed that we would not present certain confidential information about the association’s operations.

| Audit Objective | Method | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Review and evaluate the laws, rules, and regulations significant to the audit objectives. | Reviewed relevant state laws and regulations. |

| 2 | Identify the public funding received by the Los Angeles County Fair Association (association) over the past 10 years and the major categories of expenditures of those funds, including the extent to which public funds were used for staff and executive compensation. |

|

| 3 | Compare the association’s executive compensation with executive compensation of organizations of similar size. • Determined that comparable organizations include Class VII fairs under the CDFA’s classification system. |

|

| 4 | To the extent possible, evaluate whether the association’s hiring and compensation practices comply with laws, rules, policies, and generally accepted practices. |

|

| 5 | Determine whether the association’s financial and accounting practices comply with generally accepted accounting or industry standards. |

|

| 6 | Determine for each of the past 10 years whether the association has been operating at a loss and, if so, to the extent possible, determine what factors are contributing to this condition. |

|

| 7 | Evaluate whether the association’s activities are promoting its mission and whether its operations are within the parameters outlined in Government Code section 25900, et seq., which authorizes a county board of supervisors to participate in the affairs of an agricultural fair association and expend certain state funds for those purposes. |

|

| 8 | Examine whether the association’s status and filings related to its nonprofit status are in compliance with applicable requirements. |

|

| 9 | To the extent possible, examine the extent to which the association is complying with laws, rules, or policies related to the selection of its members and election of its board of directors. Determine whether this process is fair, reasonable, and avoids nepotism or the appearance of nepotism. |

|

| 10 | Review and assess any other issues that are significant to the audit. |

|

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of the Joint Legislative Audit Committee’s audit request number 2016-106, as well as information and documentation identified in the column titled Method.

Assessment of Data Reliability

The U.S. Government Accountability Office, whose standards we are statutorily required to follow, requires us to assess the sufficiency and appropriateness of the computer‑processed information that we use to materially support our findings, conclusions, or recommendations. In performing this audit, we relied upon financial information provided to us from the association’s, the county’s, CDFA’s, and Pomona’s information systems to determine the amount of state and local public funding and other assistance provided to the association from 2006 through 2015. We compared the association’s records against the public entities’ records, as well as comparing CDFA’s records against the county’s records. We found that the records generally matched each other with only minor discrepancies. Therefore, we determined that the financial information was sufficient for our purposes and that a data reliability assessment was not required.

We conducted this audit under the authority vested in the California State Auditor by Section 8543 et seq. of the California Government Code and according to generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives specified in the Scope and Methodology section of the report. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Respectfully submitted,

ELAINE M. HOWLE, CPA

State Auditor

Date:

November 10, 2016

Staff:

Nicholas Kolitsos, CPA, Audit Principal

Kathleen Klein Fullerton, MPA, Audit Principal

Joseph R. Meyer, CPA, CIA

Brigid Drury, MPAc

Brandon A. Clift, CPA, CFE

Caroline Julia von Wurden

Legal Counsel:

Heather Kendrick, Sr. Staff Counsel

For questions regarding the contents of this report, please contact Margarita Fernández, Chief of Public Affairs, at 916.445.0255.

Footnotes

1 The term audit appears frequently in the county’s internal communication and in references to this review, even though the type of engagement for which the county contracted was not an audit. Specifically, in an audit, the auditor independently develops the audit procedures. The reviewer and the county, on the other hand, agreed upon the procedures the reviewer would perform. As a result, the reviewer did not opine on the sufficiency of the procedures performed, but only made a conclusion based on his performance of the agreed-upon procedures. Go back to text

2 In 2011 the Legislature enacted law to abolish redevelopment agencies. Pomona’s Housing Authority is the successor agency to the low and moderate income housing functions of the former Redevelopment Agency. Go back to text