Audit Results

Male Employees Generally Earned More Than Female Employees During Fiscal Years 2010–11 Through 2014–15

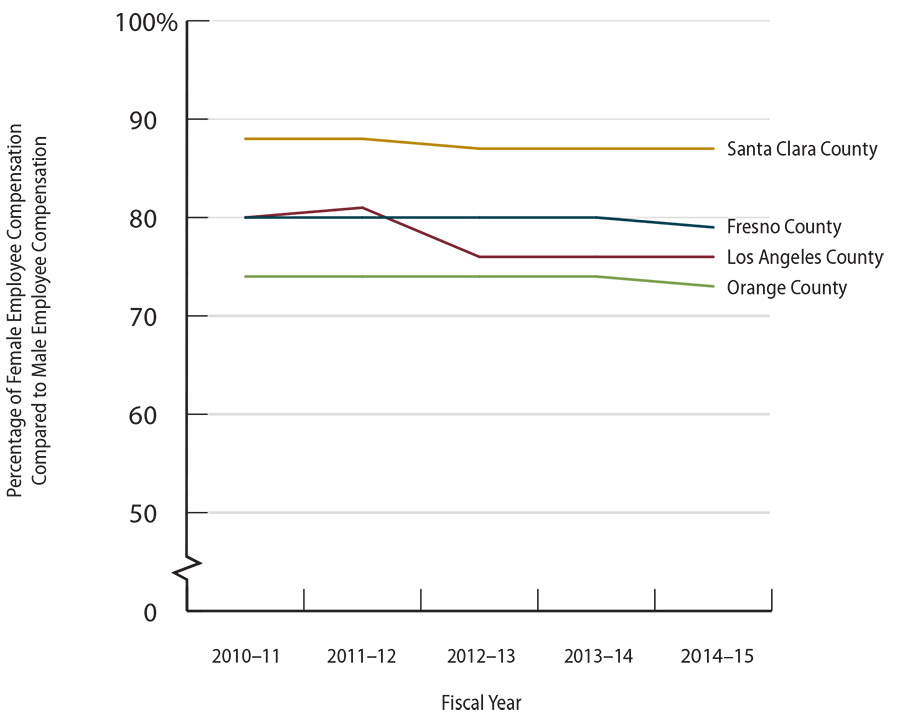

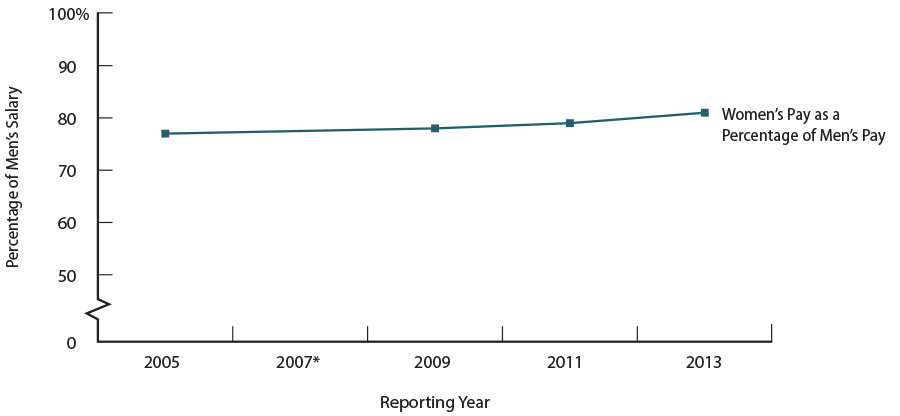

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2012 American women who worked full-time earned on average less than 77 cents for every dollar earned by their male counterparts. In other words, the aggregate pay gap between the wages of men and those of women (regardless of job classification) was roughly 23 percent. Our review of the pay data for Fresno, Los Angeles, and Orange counties (three of the four counties we visited) provided a similar result when we evaluated total average compensation, which includes salaries, employee benefits, and additional payments, such as overtime and paid leave, for certain full-time county employees.6 In Santa Clara County the pay gap was less: female employees earned, on average, between 87 percent and 88 percent of what male employees earned. The data also show that the aggregate wage gap has widened slightly at each of the four counties over the most recent five fiscal year period data was available. In fact, this measure of the pay gap in Los Angeles County grew from 20 percent in fiscal year 2010–11 to 24 percent in fiscal year 2014–15.

When evaluating the differences in average total compensation between male and female employees working in the same job classification or in groups of classifications with similar total compensation amounts, we found that there are more classifications for which men earned more than women, and that men more often held higher-compensated jobs. For nearly 4,000 county job classifications, we calculated the average total compensation for the full-time employees in each classification, regardless of gender, and assigned each classification and its employees into 13 different pay strata.7 Doing so allowed us to identify potential male-versus-female pay differences across low-paying to highly compensated county classifications. The results for fiscal year 2014–15 showed that the difference in average total compensation between male and female employees—regardless of how well compensated the position—varied between less than 1 percent and nearly 9 percent.

The Gender-Based Pay Gap Has Widened Marginally at the Four Counties We Visited, and Men Held More Jobs in the Higher-Paying Classifications

As shown in Figure 3, women earned between 73 percent and 88 percent of the aggregate pay men earned, without accounting for the specific jobs held, from fiscal years 2010–11 through 2014–15. Figure 3 also shows that this pattern has persisted over this five-year period with no clear positive trend at any county toward achieving higher levels of pay equality. In fact, the figure shows that the aggregate wage gap has slightly widened at each of the four counties. For example, in fiscal year 2010–11, Fresno County’s female employees earned roughly 80 percent of what male employees earned, but by the end of fiscal year 2014–15, female employees were earning just 79 percent of male employees’ pay. In Los Angeles County, female employees also earned roughly 80 percent of male employees’ average total compensation in fiscal year 2010–11, but this figure had dropped to 76 percent by the end of fiscal year 2014–15.

Figure 3

Average Total Compensation of Female Employees as a Percentage of Average Total Compensation of Male Employees

Fiscal Years 2010–11 Through 2014–15

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of personnel and payroll data obtained from Fresno County’s PeopleSoft Human Capital Management System, Los Angeles County’s eHR Personnel and Timekeeping System, Orange County’s County-wide Accounting and Personnel System, and Santa Clara County’s Human Resource Payroll System.

Notes: Average total compensation includes pay and benefits tracked in the counties’ personnel and payroll systems, such as regular pay, overtime pay, and employer contributions to health benefits and retirement.

This figure includes only full-time employees who were active in a single job classification for the entire fiscal year. We limited our analysis to that group of employees to mitigate the effects of midyear promotions, transfers, or other actions that can influence salary amounts and pay differences. However, our analysis for Los Angeles County may include some employees who took a leave of absence during the fiscal year because the county does not remove its employees from active status in its personnel and payroll system when they take a leave of absence.

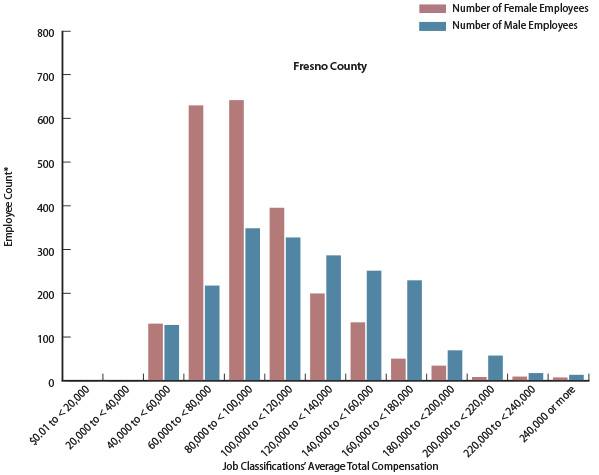

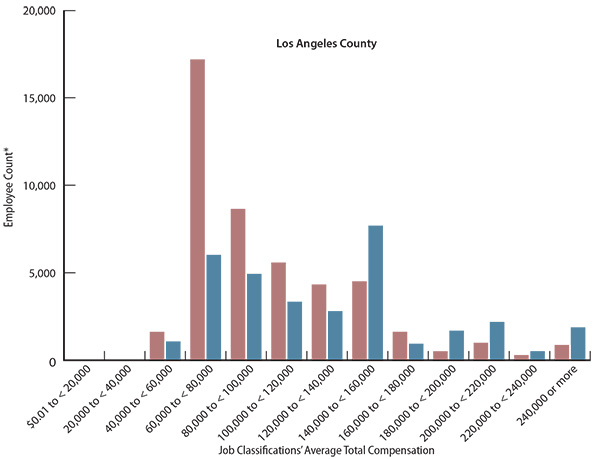

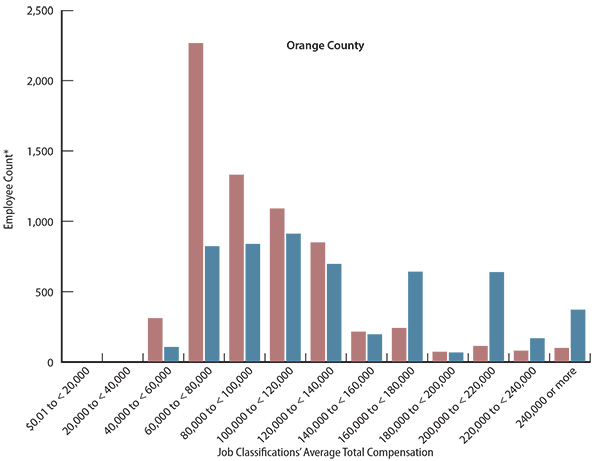

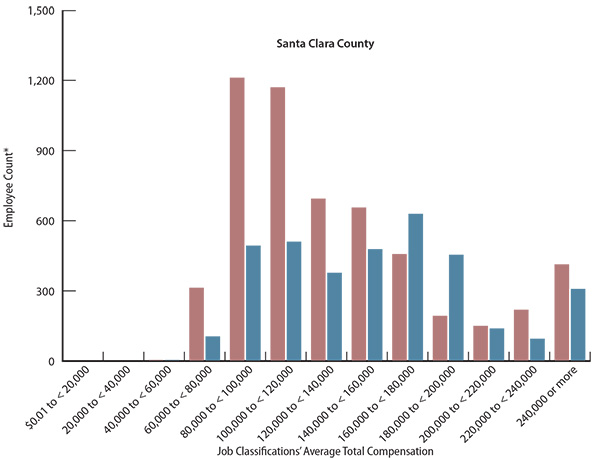

Achieving greater levels of pay equality depends not only on men and women earning equal amounts in the same classification, it also requires men and women to occupy equally both lower and more highly compensated positions. Our analysis found—as shown in Figure 4 for fiscal year 2014–15 at Fresno, Los Angeles, and Orange counties—no such equality because more men than women tended to occupy the highly compensated county classifications. Generally, we found that men outnumbered women in county job classifications for which the average total compensation was greater than $160,000, even though women accounted for between 54 percent and 60 percent of all full-time employees whose records we reviewed. However, the one exception was Santa Clara County, which had more women than men in the top three salary ranges.

When we reviewed Santa Clara County’s underlying data to understand why it appeared so different from the other three counties’ data, we found that it had a significant number of highly compensated individuals employed in health care positions, such as physicians and nurses. Of the 411 women and 306 men in the highest salary range we reviewed—classifications with average total compensation of $240,000 or more—we determined that Santa Clara County had 74 female nurses of varying types and a higher number of female physicians (118) relative to male physicians (104). On the other hand, for the three other counties we visited, we found that the top salary ranges included many law enforcement and fire positions, which were overwhelmingly filled by men. For example, for fiscal year 2014–15, Los Angeles County had 622 full-time fire captains, and the average compensation for that position was nearly $245,200. Of those 622 individuals, only four were female. Similarly, at Orange County, in fiscal year 2014–15, 551 individuals worked full-time in the position of deputy sheriff II. This position had an average total compensation of more than $210,000 per year; however, only 49 of those 551 individuals were women.

Figure 4

Distribution of Female and Male Employees Working in Low- to High-Paid Job Classifications

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of personnel and payroll data obtained from Fresno County’s PeopleSoft Human Capital Management System, Los Angeles County’s eHR Personnel and Timekeeping System, Orange County’s County-wide Accounting and Personnel System, and Santa Clara County’s Human Resource Payroll System.

Notes: Average total compensation includes pay and benefits tracked in the county’s personnel and payroll system, such as regular pay, overtime pay, and employer contributions to health benefits and retirement.

This figure includes only full‑time employees who were active in a single job classification for the entire fiscal year. We limited our analysis to that group of employees to mitigate the effects of midyear promotions, transfers, or other actions that can influence salary amounts and pay differences. However, our analysis for Los Angeles County may include some employees who took a leave of absence during the fiscal year because the county does not remove its employees from active status in its personnel and payroll system when they take a leave of absence.

* The employee counts represent individuals in jobs in which the average total compensation falls within the salary ranges shown. For example, 17 Orange County employees (regardless of sex) worked as cashiers for the entire fiscal year and the average total compensation for all 17 employees was nearly $66,000, with the lowest paid employee earning $55,000 and the highest more than $80,000. All 17 employees still appear within the $60,000 to < $80,000 range because the total average compensation for a cashier was nearly $66,000.

In Specific Classifications or Groups of Classifications With Similar Compensation, Male Employees Often Make More Than Their Female Counterparts

We focused our review on specific job classifications or groups of job classifications with similar compensation and found that men often earned more than women on average. We saw 78 classifications across the four counties that had disparity levels of 20 percent or greater. In 56 of these classifications, men earned more than women. In 22 of the 78 classifications, women had higher salaries. Those 78 classifications accounted for roughly 4 percent of all job classifications in the four counties and less than 2 percent of the county employees included in our analysis. For the five classifications with both high disparity levels and a significant number of employees (or more than 20), two of the five were in Los Angeles County and pertained to fire-fighting positions. These two positions were significantly different from the remaining 76 classifications as they each had more than 600 male employees and six or fewer female employees. The other three classifications were in Santa Clara County and had no such commonality because they pertained to stock clerks, clinical nurses, and aides to the county’s board of supervisors. Table 2 provides the overall distribution of county job classifications by level of gender-based pay disparity. The table shows more classifications in which men earned more than women: men earned more in 843 classifications, while women earned more in 492 classifications. However, when we looked at the total population of employees making up the 1,855 classifications shown in Table 2, we found that for 71 percent of the employees, the difference in pay between men and women in the same position varied by no more than 5 percent.

| COUNTY | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEVEL OF PAY DISPARITY BY GENDER | FRESNO | LOS ANGELES | ORANGE | SANTA CLARA | TOTAL | TOTAL WITH DISPARITY GREATER THAN 20 PERCENT | ||

| Number of job classifications in which women earn more by these percentages: | >30% | 0 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 12 | 22 | |

| >20–30% | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 10 | |||

| >10–20% | 10 | 61 | 8 | 23 | 102 | |||

| >5–10% | 13 | 91 | 19 | 37 | 160 | |||

| >2–5% | 20 | 116 | 33 | 39 | 208 | |||

| Subtotal of job classifications in which women earn more than men | 492 | |||||||

| Number of job classifications with pay disparities of 2% or less for either gender | 50 | 269 | 105 | 96 | 520 | |||

| Number of job classifications in which women earn more by these percentages: | >30% | 0 | 15 | 0 | 6 | 21 | 56 | |

| >20–30% | 3 | 25 | 1 | 6 | 35 | |||

| >10–20% | 15 | 102 | 20 | 37 | 174 | |||

| >5–10% | 16 | 161 | 47 | 59 | 283 | |||

| >2–5% | 27 | 173 | 61 | 69 | 330 | |||

| Subtotal of job classifications in which men earn more than women | 843 | |||||||

| Total job classifications with both genders | 155 | 1,025 | 297 | 378 | 1,855 | |||

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of personnel and payroll data obtained from Fresno County’s PeopleSoft Human Capital Management System, Los Angeles County’s eHR Personnel and Timekeeping System, Orange County’s County-wide Accounting and Personnel System, and Santa Clara County’s Human Resource Payroll System.

Notes: The analysis shown above is based on average total compensation, which includes pay and benefits tracked in the counties’ personnel and payroll system, such as regular pay, overtime pay, and employer contributions to health benefits and retirement.

This table includes only full-time employees who were active in a single job classification for the entire fiscal year. We limited our analysis to that group of employees to mitigate the effects of midyear promotions, transfers, or other actions that can influence salary amounts and pay differences. However, our analysis for Los Angeles County may include some employees who took a leave of absence during the fiscal year because the county does not remove its employees from active status in its personnel and payroll system when they take a leave of absence.

We further examined how often county job classifications had either men or women earning higher average total compensation than did employees of the opposite gender. When analyzing each county’s pay data, we grouped classifications falling into certain salary ranges based on the earnings of the individuals holding those positions. We arranged each classification—and its male and female employees—into one of 13 different salary ranges (or strata) based on each classification’s average total compensation. We found that roughly 50 percent to 60 percent of all county classifications had men as the higher-earning gender. Table 3 lists, by pay strata, how many county classifications had either men or women earning higher average total compensation than members of the opposite gender earned. For example, Table 3 demonstrates that at Fresno County men earned more than women in 12 of the 17 classifications in which the average total compensation was $240,000 or greater in fiscal year 2014–15.

After comparing the results shown previously in Figure 4—illustrating the distribution of female employees across different compensation levels—with Table 3, we see that women often occupy classifications at lower levels of compensation, yet men still have the higher average total compensation in more of those same classifications. For example, Table 3 shows that Los Angeles County has more classifications in which men earn more than women across all pay strata. When looking specifically at classifications in Los Angeles County with average total compensation between $80,000 and less than $100,000, men earned higher average total compensation in 201, or 64 percent, of those classifications, while women earned more in 114, or 36 percent, of the classifications. However, the data for Los Angeles County show that 8,609 women, or 64 percent of 13,506 employees, fall under those same classifications compared to 4,897 men, or 36 percent. Similarly, in Fresno County, men earned more than women in 41, or 58 percent, of the 71 classifications, with average total compensation ranging between $80,000 and less than $100,000; however, 640, or 65 percent, of the 987 full-time employees in those same classifications were women. Finally, in Santa Clara County, where there were more women than men in nearly all salary strata and where women represented 60 percent of the full-time workforce we reviewed, men earned the higher average total compensation in 499, or 52 percent, of the 960 different county classifications.

| NUMBER OF JOB CLASSIFICATIONS IN WHICH FEMALE EMPLOYEES OR MALE EMPLOYEES HAD HIGHER AVERAGE TOTAL COMPENSATION | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRESNO COUNTY | LOS ANGELES COUNTY | ORANGE COUNTY | SANTA CLARA COUNTY | ||||||||||

| JOB CLASSIFICATIONS WITH AVERAGE TOTAL COMPENSATION BETWEEN | FEMALE | MALE | FEMALE | MALE | FEMALE | MALE | FEMALE | MALE | |||||

| 1 | $240,000 or more | 5 | 12 | 89 | 200 | 3 | 27 | 49 | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 220,000 to < 240,000 | 6 | 3 | 26 | 29 | 3 | 5 | 22 | 26 | ||||

| 3 | 200,000 to < 220,000 | 4 | 7 | 28 | 37 | 1 | 2 | 23 | 24 | ||||

| 4 | 180,000 to < 200,000 | 6 | 10 | 27 | 51 | 3 | 3 | 39 | 44 | ||||

| 5 | 160,000 to < 180,000 | 9 | 15 | 58 | 65 | 3 | 11 | 52 | 60 | ||||

| 6 | 140,000 to < 160,000 | 16 | 30 | 67 | 106 | 11 | 21 | 57 | 87 | ||||

| 7 | 120,000 to < 140,000 | 25 | 33 | 95 | 137 | 20 | 67 | 53 | 59 | ||||

| 8 | 100,000 to < 120,000 | 22 | 30 | 111 | 184 | 45 | 68 | 83 | 72 | ||||

| 9 | 80,000 to < 100,000 | 30 | 41 | 114 | 201 | 60 | 71 | 71 | 67 | ||||

| 10 | 60,000 to < 80,000 | 41 | 32 | 124 | 137 | 59 | 39 | 12 | 14 | ||||

| 11 | 40,000 to < 60,000 | 13 | 18 | 22 | 31 | 10 | 8 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 12 | 20,000 to < 40,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 13 | 0.01 to < 20,000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Totals | 177 | 231 | 761 | 1,180 | 218 | 322 | 461 | 499 | |||||

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of personnel and payroll data obtained from Fresno County’s PeopleSoft Human Capital Management System, Los Angeles County’s eHR Personnel and Timekeeping System, Orange County’s County-wide Accounting and Personnel System, and Santa Clara County’s Human Resource Payroll System.

Notes: Average total compensation includes pay and benefits tracked in the county’s personnel and payroll system, such as regular pay, overtime pay, and employer contributions to health benefits and retirement.

This table includes only full-time employees who were active in a single job classification for the entire fiscal year. We limited our analysis to that group of employees to mitigate the effects of midyear promotions, transfers, or other actions that can influence salary amounts and pay differences. However, our analysis for Los Angeles County may include some employees who took a leave of absence during the fiscal year because the county does not remove its employees from active status in its personnel and payroll system when they take a leave of absence.

If a job classification only has one gender, we count that gender as earning more.

█ = In most positions in this compensation range, women earned more, on average, than men earned.

█ = In most positions in this compensation range, men earned more, on average, than women earned.

When looking at groups of job classifications that have low to high levels of total average total compensation, we also found that the differences in compensation between men and women ranged from less than 1 percent to nearly 9 percent. Moreover, we found that the difference in pay between men and women was often less than 4 percent, as shown in Table 4. For example, in job classifications with total average compensation of $240,000 or more at Orange County, men’s average pay was $268,122, while women in the same classifications earned, on average, $265,165—a difference of roughly 1.1 percent. After comparing average total compensation of both men and women in various classifications spanning 13 different compensation ranges at four different counties—52 different compensation ranges in total—we identified three salary ranges in which the difference in average pay between male and female employees exceeded 4 percent.

| FRESNO COUNTY | LOS ANGELES COUNTY | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JOB CLASSIFICATIONS WITH AVERAGE TOTAL COMPENSATION BETWEEN | AVERAGE TOTAL COMPENSATION | PERCENTAGE DIFFERENCE IN AVERAGE TOTAL COMPENSATION | AVERAGE TOTAL COMPENSATION | PERCENTAGE DIFFERENCE IN AVERAGE TOTAL COMPENSATION | |||||

| FEMALE | MALE | FEMALE | MALE | ||||||

| 1 | $240,000 or more | $304,389 | $292,430 | 4.1% | $286,633 | $288,685 | 0.7% | ||

| 2 | 220,000 to < 240,000 | 225,632 | 230,597 | 2.2 | 228,689 | 236,588 | 3.5 | ||

| 3 | 200,000 to < 220,000 | 206,772 | 210,585 | 1.8 | 203,683 | 210,561 | 3.4 | ||

| 4 | 180,000 to < 200,000 | 184,816 | 189,213 | 2.4 | 184,433 | 183,886 | 0.3 | ||

| 5 | 160,000 to < 180,000 | 168,077 | 173,649 | 3.3 | 169,192 | 170,912 | 1.0 | ||

| 6 | 140,000 to < 160,000 | 146,705 | 148,342 | 1.1 | 146,652 | 159,513 | 8.8 | ||

| 7 | 120,000 to < 140,000 | 127,885 | 130,128 | 1.8 | 128,586 | 128,785 | 0.2 | ||

| 8 | 100,000 to < 120,000 | 110,148 | 110,596 | 0.4 | 112,904 | 114,811 | 1.7 | ||

| 9 | 80,000 to < 100,000 | 87,797 | 87,606 | 0.2 | 88,794 | 91,888 | 3.5 | ||

| 10 | 60,000 to < 80,000 | 67,659 | 67,903 | 0.4 | 69,223 | 69,873 | 0.9 | ||

| 11 | 40,000 to < 60,000 | 51,834 | 52,586 | 1.5 | 55,470 | 55,770 | 0.5 | ||

| 12 | 20,000 to < 40,000 | 0 | 0 | NA* | 0 | 32,728 | NA† | ||

| 13 | 0.01 to < 20,000 | 0 | 0 | NA* | 0 | 7,991 | NA† | ||

| ORANGE COUNTY | SANTA CLARA COUNTY | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JOB CLASSIFICATIONS WITH AVERAGE TOTAL COMPENSATION BETWEEN | AVERAGE TOTAL COMPENSATION | PERCENTAGE DIFFERENCE IN AVERAGE TOTAL COMPENSATION | AVERAGE TOTAL COMPENSATION | PERCENTAGE DIFFERENCE IN AVERAGE TOTAL COMPENSATION | |||||

| FEMALE | MALE | FEMALE | MALE | ||||||

| 1 | $240,000 or more | $265,165 | $268,122 | 1.1% | $304,051 | $330,172 | 8.6% | ||

| 2 | 220,000 to < 240,000 | 232,336 | 237,610 | 2.3 | 227,252 | 228,087 | 0.4 | ||

| 3 | 200,000 to < 220,000 | 207,684 | 210,621 | 1.4 | 208,823 | 213,317 | 2.2 | ||

| 4 | 180,000 to < 200,000 | 193,647 | 193,341 | 0.2 | 187,717 | 188,790 | 0.6 | ||

| 5 | 160,000 to < 180,000 | 164,884 | 166,758 | 1.1 | 166,024 | 171,332 | 3.2 | ||

| 6 | 140,000 to < 160,000 | 149,038 | 151,131 | 1.4 | 147,206 | 151,779 | 3.1 | ||

| 7 | 120,000 to < 140,000 | 130,189 | 132,470 | 1.8 | 128,848 | 130,219 | 1.1 | ||

| 8 | 100,000 to < 120,000 | 107,737 | 109,215 | 1.4 | 107,915 | 108,097 | 0.2 | ||

| 9 | 80,000 to < 100,000 | 89,371 | 90,641 | 1.4 | 90,739 | 89,416 | 1.5 | ||

| 10 | 60,000 to < 80,000 | 68,688 | 67,597 | 1.6 | 77,218 | 75,637 | 2.1 | ||

| 11 | 40,000 to < 60,000 | 58,822 | 58,725 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | NA* | ||

| 12 | 20,000 to < 40,000 | 0 | 0 | NA* | 0 | 0 | NA* | ||

| 13 | 0.01 to < 20,000 | 0 | 0 | NA* | 0 | 0 | NA* | ||

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of personnel and payroll data obtained from Fresno County’s PeopleSoft Human Capital Management System, Los Angeles County’s eHR Personnel and Timekeeping System, Orange County’s County-wide Accounting and Personnel System, and Santa Clara County’s Human Resource Payroll System.

Notes: Average total compensation includes pay and benefits tracked in the county’s personnel and payroll system, such as regular pay, overtime pay, and employer contributions to health benefits and retirement.

This table includes only full-time employees who were active in a single job classification for the entire fiscal year. We limited our analysis to that group of employees to mitigate the effects of midyear promotions, transfers, or other actions that can influence salary amounts and pay differences. However, our analysis for Los Angeles County may include some employees who took a leave of absence during the fiscal year because the county does not remove its employees from active status in its personnel and payroll system when they take a leave of absence.

█ = Women earned more, on average, than men did.

█ = Men earned more, on average, than women did.

* Not applicable because there were no female or male county employees in positions averaging this amount of total compensation.

† Not applicable because there were no female county employees in positions averaging this amount of total compensation.

Significant Pay Disparities Within Job Classifications Often Occurred Because of County Workers’ Full-Time Versus Part-Time Employment

Although we found no evidence of gender discrimination pertaining to employee pay, our review of 161 county employees working in 46 job classifications revealed a multitude of factors that can result in differences in pay among employees working within the same job classification. These factors included the following: the starting salary for each employee in his or her current county job, which can often be influenced by prior pay in a previous county job; the length of time spent by the employee in his or her current job; and whether the employee worked full-time or part-time during the entire fiscal year. Our review of 46 job classifications found that the disparities in pay were often influenced by a combination of these factors, while part-time versus full-time employment was the single most significant factor.8

To understand why differences in salary exist and to determine which, if any, of the above factors contribute the most to pay disparities between men and women, we examined groups of employees within the same job classification and county department (regardless of full-time status) from fiscal year 2014–15. Our review focused on 46 job classifications that had at least 20 or more employees and that had at least five from each gender. The classifications we selected for review included ones where the disparity in pay varied from as little as 2 percent to as much as 75 percent, with many displaying variances of 20 percent or more. However, upon closer review, we determined that the most significant reason for these high pay disparities within the job classifications resulted from employees who were either working part time or less than a full year within the classification. For example, we saw one instance where a female deputy public defender I’s annual salary was roughly $26,000 less than her male counterpart’s salary, despite having similar time on the job; however, the difference was caused by the female employee’s decision to take six months off without pay. To compensate for employees who either did not work an entire year or worked only part time, we recalculated the pay disparity in each of the 46 job classifications based on employees who worked full-time in each classification during fiscal year 2014–15 and earned at least the expected minimum annual salary. Following this recalculation, the pay disparities often dropped to less than 2 percent, with no single classification having a disparity of over 10 percent.

With pay disparities between the genders often occurring at 2 percent or less, we next attempted to determine what other factors significantly contributed to the remaining pay disparities by reviewing the salary earnings for 161 employees in these 46 job classifications. We primarily selected employees who earned at least the minimum salary amounts for their classifications and identified employee records for review based on attributes that could be indicative of inappropriate pay disparities, such as employees who had worked within a classification for similar amounts of time but earned different amounts of regular pay, and employees who worked within a classification for a short time but earned pay that was beyond the normal hiring rate.

The results of our review found that of the remaining factors, no single factor contributed the most to the remaining pay disparities. Instead, we observed certain county pay practices that can, but do not always, lead to one employee earning more than another in a particular job classification. For example, we frequently observed county employees obtaining a starting salary that was above the normal recruiting rate—occurring for 106, or 66 percent, of the 161 employees whose records we reviewed—because the employee had transferred or promoted from another county job. As discussed later in the report, counties have these rules to ensure their employees do not take a pay cut when they transfer or promote into a higher position. For example, in Los Angeles County, we reviewed the salary placements for two employees within the senior board specialist classification. We noted a male and female employee who promoted into this classification on the same day, but the male employee initially earned a monthly salary of $4,773, whereas the female employee initially earned a monthly salary of $4,521—5.3 percent less. The male employee’s new monthly salary of $4,773 was based on his previous salary of $4,521 per month in his previous county job, whereas the female employee had previously earned $4,282 per month in her last job with the county. We calculated that the male employee and female employee in our example each earned a 5.6 percent increase as a result of their promotions, and we determined that this raise was consistent with the county’s policies for promotions at the time. Although the county’s application of the policy was consistent with its rules, it yielded different salary levels in this instance based on the employees’ individual salary histories as opposed to their gender.

We also saw that county employees who changed jobs within the county did not always receive starting pay that was higher than the amounts earned by new county employees. For example, Santa Clara County hired a new employee for an attorney position at the third salary step because of his previous experience as a trial attorney, while an existing county employee promoted into the same job classification at the lower first salary step.

Aside from considering prior pay, we also frequently observed instances where the county set salaries for new employees at the minimum salary step (or hiring rate), occurring in 28 of the 48 new employees we reviewed. Thus, when we compared employees who entered a classification as a new hire to those who entered due to transfers or promotions, the new employees, at times, earned less. For example, Los Angeles County hired a new county employee as a welfare fraud investigator trainee at the first salary step and at the same time hired three others—each of whom had previously held other county jobs—at higher salary rates when compared to the new employee. For 11 of the 48 new employees, we also noted that counties established starting pay above the normal hiring rate in order to address recruiting challenges such as employment shortages within a particular classification. For example, Los Angeles County’s data show that the difference between men’s pay and women’s pay in the deputy public defender I position was nearly 30 percent, or less than 1 percent if we exclude employees who worked less than the entire fiscal year. We selected a male and female deputy public defender I to compare because the male employee had less time served in the position, yet earned more than his female counterpart in fiscal year 2014–15. However, upon closer review, we determined that, at the time when the male employee was hired in June 2014, the Los Angeles County Chief Executive Officer (chief executive officer) had authorized an adjusted minimum rate for the deputy public defender I position at step 6—or $6,018 per month—in order to assist the Public Defender’s Office’s recruitment and retention efforts. However, when the female employee was hired, earlier in February 2014, this adjusted hiring rate was not in effect and so the hiring rate at that time was only $5,255 per month. The difference in these two employees’ salaries did not depend on their gender; rather, the different dates on which they were hired created the disparity. We also noted that the chief executive officer’s memo required that all employees earning below the step 6 salary rate of $6,018 per month be advanced, and we saw evidence that the female deputy public defender I’s salary was adjusted retroactively.

Counties are also able to pay new county employees at a higher salary step for those employees who exceed minimum qualifications and we found that counties placed 9 of 48 new employees (three men and six women) at a salary level that was beyond the minimum hiring rate. For example, we selected the clinical social worker I classification in Orange County and compared two employees with similar years of service in the classification, noting that the female employee earned over $10,000 more during fiscal year 2014–15 than the amount earned by the male employee during the same period. However, when we reviewed the salary information, we found that the female employee was hired at a step 7 salary rate because of her two years of previous experience in the same position as a contractor with the county. On the other hand, the male employee promoted into the same job classification at the minimum salary rate, step 1 from another county position. Orange County’s policies allow its hiring mangers to request special salary step placement for an employee whose previous experience enables him or her to make a greater contribution to the county. The application of the policy is at the discretion of the hiring manager based on his or her assessment of the new employee’s qualifications.

Finally, for seven of the 161 employee records we reviewed, we determined that while the job classification of physician was the same, each employee had different medical specialties or other circumstances that made them difficult to compare. For example, we reviewed two physicians (a man and a woman) who each worked full-time and were hired during the same month and year into the same medical department at the Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, but they earned different rates of pay, with the male physician earning $149.04 per hour, or roughly $310,000 annually, and the female physician earning 13 percent less, or $129.81 per hour, a rate that totals nearly $270,000 annually. However, the male physician specialized in gastroenterology, and the female physician specialized in cardiology, making these two positions difficult to compare. In general, the smaller remaining pay disparities we identified were the result of multiple pay practices in the counties that—taken together—cause employees, regardless of gender, to earn different amounts.

Counties Applied Some Aspects of Their Hiring and Promotions Processes Equally, but Their Rationales for Selecting Successful Candidates Remain Unclear

As part of our audit, we examined whether the four counties we visited consistently followed key hiring and promotional rules for both male and female candidates. We examined 240 different hiring or promotional decisions (60 for each county) over a two-year period covering fiscal years 2013–14 and 2014–15. We evaluated in particular whether the counties engaged in a competitive recruitment process, whether the successful candidate achieved sufficiently high scores on competitive hiring exams, whether both male and female candidates were successful on these exams, and whether both men and women were contacted for hiring interviews. However, although there was sufficient documentation of the process leading up to the hiring decisions, three of four counties did not always document why they ultimately chose certain candidates over others.

For county employees appointed to classified positions or for those governed by counties’ merit system rules (as described in the Introduction), all four counties treated male and female candidates equally during the parts of the hiring and promotions we reviewed.9 Counties frequently followed competitive hiring practices to fill vacant classified positions, placed more women than men on certified eligibility lists, and contacted more women than men for hiring interviews. However, the counties often did not maintain documentation explaining their rationales for choosing particular candidates over others who were also qualified for the positions. According to the county policies and practices we observed in Fresno, Los Angeles, and Orange counties, county management does not expect documentation of such decision making. As a result, for many of the hiring decisions we reviewed at these counties, the rationale for selecting a particular candidate over others who competed for the positions was unclear and hindered a more thorough evaluation of whether employers were objectively selecting men and women based on job-related criteria. In contrast, the policies and practices at Santa Clara County do require such documentation and provide a model or best practice that, in our view, should be used by other counties. Employers are not required under federal or state law to document why they choose particular candidates over others for employment, and the State’s regulations governing the counties’ merit-based personnel systems do not cover this important topic.

The first element of the hiring and promotions process we evaluated at each of the four counties was the extent to which they engaged in a competitive recruitment process to fill their vacancies. All four counties had the general expectation in their personnel rules that competition would be the standard process for filling classified positions. Of the 240 hiring and promotional decisions we collectively reviewed at the four counties, 195 decisions pertained to the counties filling a classified position. During our review, we found that the counties engaged in a competitive hiring process for 154, or 79 percent, of those 195 classified hiring decisions, such as by issuing hiring announcements seeking qualified candidates and describing the counties’ evaluation methods for selecting candidates. The announcements clearly provided applicants with an understanding of the minimum requirements for the position, and, at times, any other desirable qualifications that the county was looking for when attempting to fill the vacant position. All of the advertisements we reviewed also provided potential applicants with additional information about the hiring process, such as the application filing periods, the ways to apply, and the times and places of examination, when necessary.

For the remaining 41 of 195 classified positions for which the county did not follow a competitive process, we concluded that the counties had made decisions to forgo competition that were consistent with their local policies and procedures. For example, Fresno, Orange, and Santa Clara counties generally had policies that were variations on the idea that competition for certain classified positions was not needed for promotions that are within a series of related classifications (or positions), such as promotions from a position as human resources assistant I to a human resources assistant II. This practice was the most common reason for the lack of competition for classified positions, occurring in 33 of the 41 instances in which competition did not take place. In these cases, the three counties generally determined that the employee in the lower-level position had attained the skills necessary for advancement to the next level and promoted that individual.10 For example, in Orange County, we reviewed a promotional decision for an employee moving from social worker I to social worker II. Orange County determined that an employee had demonstrated sufficient skill and ability to warrant promotion to the next classification within the “social worker” series, and our review of the employee’s file noted that the employee met the minimum qualifications six months experience as a social worker I with Orange County, and the employee’s supervisor recommended her for the social worker II position.

In the remaining eight of 41 cases in which competition did not occur for a classified position, the counties’ decisions still appeared appropriate as they pertained to instances when employees were temporarily promoted to a position in order to provide extra help, or when the appointment was the result of various other personnel decisions, such as the lateral transfer of an existing employee between positions or the rehiring of a former employee who was previously laid off, among other reasons. Regardless, we did not see any evidence that the decision to avoid competition disadvantaged female employees. In fact, for the 41 instances in which counties did not follow competitive processes for classified positions, female employees were appointed to the positions in 30 instances, or for 73 percent of the vacancies.

For each of the 154 competitive hiring or promotional decisions we reviewed for classified employees, we also examined whether the successful candidate had passed screening exams to warrant further advancement in the county’s hiring process. In addition, we examined how many men versus women successfully passed these screening exams for placement on certified eligibility lists and whether we saw evidence that roughly equal numbers from both male and female employees were being contacted for hiring interviews. According to our review, all 154 candidates who were ultimately successful in securing county employment had passed the counties’ initial screening exams. For example, according to Santa Clara County’s merit system rules, candidates must receive a cumulative score of 70 percent to be considered potentially competitive for a position. Continuing the example, the candidate we selected for review not only passed the accounting assistant examination but also attained one of the highest scores. His high examination score placed him on the eligible list and qualified him for a final interview.

In addition to our observation that the 154 winning candidates passed their screening exams, Table 5 shows that, regardless of who ultimately obtained employment, women were often successful at both getting on certified eligibility lists and receiving hiring interviews. In fact, the four counties placed more women than men, on average, on these lists and more often interviewed female candidates for the hiring decisions we reviewed. The results shown in Table 5 seem largely consistent with the overall demographics of the employees at the four counties included in our audit. Based on county records, women represent between roughly 54 and 60 percent of each county’s workforce.

| FRESNO COUNTY | LOS ANGELES COUNTY | ORANGE COUNTY | SANTA CLARA COUNTY | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVERAGE NUMBER | AVERAGE PERCENTAGE | AVERAGE NUMBER | AVERAGE PERCENTAGE | AVERAGE NUMBER | AVERAGE PERCENTAGE | AVERAGE NUMBER | AVERAGE PERCENTAGE | |

| Candidates on counties' certified eligibility lists for classified positions | ||||||||

| Female | 21 | 65% | 21 | 65% | 21 | 65% | 21 | 65% |

| Male | 9 | 29 | 30 | 45 | 16 | 34 | 6 | 38 |

| Total of averages* | 32 | 94% | 66 | 100% | 46 | 98% | 16 | 82% |

| Candidates who received interviews for classified positions† | ||||||||

| Female | 13 | 60% | NA† | NA† | 10 | 58% | 5 | 50% |

| Male | 7 | 33 | NA† | NA† | 7 | 41 | 5 | 50 |

| Total of averages* | 22 | 93% | NA† | NA† | 17 | 99% | 10 | 100% |

Source: California State Auditor’s review of Fresno, Los Angeles, Orange, and Santa Clara counties’ hiring records for 154 competitive hiring and promotional decisions for classified employees.

* The average number and average percentage may not add to the correct number or to 100 percent because we could not determine candidates’ sex based on written records.

† Not all counties are required to maintain data regarding the number of candidates interviewed for a particular job classification, and Los Angeles County generally did not maintain such records for the competitive hiring and promotional decisions related to the 51 classified positions we reviewed.

Finally, for those 154 competitive hiring decisions, we attempted to review documents explaining each county’s rationale for choosing the successful candidate at the time the hiring or promotional decision was made. Understanding each county’s rationale is critical, in our view, to evaluating whether county employers are treating men and women equally by basing selection decisions on objective and job-related criteria. Unfortunately, county officials could only provide evidence explaining why they chose the successful candidates, or, alternatively, why they did not select other candidates in just 39, or 25 percent, of the 154 competitive hiring or promotional decisions we reviewed. For those hiring decisions that included a rationale, Santa Clara was the county that most often documented why certain candidates were selected over others, doing so in all 26 of the competitive hiring and promotional decisions we reviewed. Santa Clara County’s documentation often notes the deficiencies of the unsuccessful candidates. For example, the documentation included a statement that an applicant for an accountant assistant position lacked experience using SAP accounts payable software. Santa Clara County’s Human Resources Practices Manual instructs hiring managers that “[they] must be able to show appropriate justification for all hiring decisions,” further requiring that managers “be certain that the candidate selected is objectively the most qualified, or at least equally qualified according to the criteria set.” Perhaps more importantly, Santa Clara County’s manual provides examples of appropriate and inappropriate rationales regarding candidate selection. Most of the “appropriate” rationales focus on ways to explain why a candidate was not chosen, such as by documenting the following: “Not selected, qualifications were good, but did not have direct experience in a medical setting, while other applicants did.” Examples of inappropriate rationales cited in Santa Clara County’s manual include such statements as the following: “Not selected, not as qualified as candidate selected.”

However, not all counties have the same expectations as those of Santa Clara County. We found that Los Angeles County’s merit system rules do not establish a requirement that hiring managers document their rationale for selecting a particular individual over other eligible candidates from a certified eligibility list. We saw that the hiring managers in individual county departments often did not maintain such records, and as a result, we were unable to evaluate the hiring departments’ hiring rationales for 41 of the 51 hiring decisions we reviewed. When providing an explanation for the limited documentation, one hiring manager in the county’s Department of Public Social Services indicated that performing selection interviews and documenting the results and rationale behind the hiring decision are not required under the county’s hiring rules. Other managers within Los Angeles County provided similar explanations. For example, according to the human resources manager at the Los Angeles County’s registrar and clerk’s office, civil service rules do not require the hiring authority to interview a specific number of candidates, and county hiring managers may appoint any reachable candidate without going through a formal selection interview process. Explaining her position further, this manager stated that all candidates who can be contacted for hiring interviews are all equally eligible for appointment under the county’s hiring rules. In our view, this makes proper documentation even more important because there should be a valid reason for selecting the successful candidate.

Fresno County’s personnel rules require department heads to maintain records of employment selections, including comments relative to the qualifications of the eligible candidate selected, but they do not require departments to document the justification for why one candidate was selected over another. When we reviewed the hiring and promotional files at Fresno County, available documentation for the selection process was often limited to hard copy interview notes and information contained in an electronic application system called NeoGov. For eligible candidates who received interviews, the NeoGov system provided such limited information as “rejected–not selected” without further information explaining the reasons for the rejections. Orange County’s recruitment rules and policies similarly do not establish an expectation that hiring managers document why they chose a particular male or female candidate over others from the eligible candidate pool. As in Fresno County, Orange County also uses the NeoGov system, and its records identify who was offered the position but not the reason why—or why the hiring manager did not choose other candidates who were interviewed.

Even though neither federal nor state employment law explicitly requires employers to document why they choose particular candidates over others when making employment decisions, if challenged, employers must successfully demonstrate that the decision to hire an individual (or not to hire another) was not the result of a discriminatory employment practice. We believe Santa Clara County’s policies establish a best practice to limit counties’ risk against such claims. We also believe that it is reasonable to expect that hiring managers have some legitimate basis for selecting candidates and that managers document these decisions, which could be used to defend a hiring decision if challenged. Although county officials may claim that all candidates who can be interviewed from certified eligibility lists are “equal” in terms of their qualifications, those male and female candidates who are not selected may disagree. Ultimately, documentation needs to show a nondiscriminatory basis for all candidate selections.

Finally, our audit also reviewed 45 unclassified positions, 39 of which were executive-level appointments to positions that received salaries (not including benefits or other forms of compensation) of at least $120,000 per year. These unclassified positions were exempt from the merit system rules that we describe earlier. For example, the newly elected Fresno County district attorney appointed an assistant district attorney. This at-will employee was a former chief deputy district attorney and did not undergo the same competitive process generally required for the county’s classified employees before appointment—nor was she required to do so. Unlike classified employees, at-will employees are not entitled to civil service status, and they may be terminated at the discretion of the employer at any time, so long as it is for a lawful reason. As in the case of selection for classified positions, selection of candidates to fill unclassified positions usually does not require the counties to justify these hiring decisions. Nevertheless, we found that counties did document the reasons for selecting certain candidates—or for not choosing other candidates—in three of 45 unclassified selections we reviewed. However, because of the lack of documentation for the hiring decisions for most of those at-will positions, we were prevented from reviewing the number of male and female candidates interviewed, or determining whether the counties were objectively selecting men and women based on job-related criteria.

Counties’ Salary-Setting Decisions Complied With Their Policies, but Factors Other Than Employees’ Abilities Influenced Salary Levels

One of our audit objectives was to evaluate whether the four counties we visited complied with laws and local policies regarding the salary-setting process. Although neither federal nor state law expressly mandates how employers should set employee salaries, each county has established a set of rules governing how employee pay is determined, and we observed that the four counties follow those local rules. For new employees appointed to classifications with incremental salary steps within a salary range, the counties we reviewed often had rules requiring that employees be paid the minimum rate unless an employee possessed unusual or unique qualifications. County hiring managers decide when to request a higher salary for a new employee whose qualifications are beyond the minimum required for the position. In other cases, salary determinations can be the result of undocumented negotiations between the employee and the county that result in the employee receiving a pay amount that is within a broad salary range.

For each of the salary-setting decisions we reviewed for 240 employees (108 men and 132 women), we identified each employee’s salary amount, evaluated whether the salary was set at or above the minimum amount established for the particular position, and determined the reasons—to the extent possible—why any employee was paid more than the minimum salary for the classification. We also looked for evidence of whether employees of one gender or the other more often received pay above the minimum rate.

The results of our review found that a county’s decision regarding whether to offer a higher salary amount to an employee was based on a variety of factors that may have nothing to do with the employee’s skills or abilities. Such considerations that are external to the candidate can include the following: the number of qualified candidates in the labor market, whether the county has strictly enforced policies of only hiring new county employees at the minimum salary rate, and whether the salary-setting decision is for an existing county employee who is transferring or promoting into a new county classification, in which case the new salary amount can be influenced by what he or she earned in the prior county classification.

The data from our selection showed that women were more likely than men to begin county employment at the minimum salary rates for their positions (79 percent of women versus 63 percent for men). Nevertheless, both genders benefitted roughly equally from county pay practices that consider prior pay upon transfer or promotion, with 80 percent of the women and 83 percent of the men receiving starting salary rates above the minimum amounts.

Women Were More Likely Than Men to Begin County Employment at Minimum Salary Levels, and Factors Other Than Ability Can Influence What Salary Rates Are Offered

The four counties we visited have compensation policies that generally, but do not always, direct new employees to start at step 1 of the salary schedule for their classification. Nevertheless, these policies could place both men and women at a disadvantage when their qualifications exceed the minimum requirements for the position. Of the 240 salary decisions we reviewed, 57 pertained to cases in which the employee was new to county service and was entering a county classification with the pay based on a salary schedule with a minimum and maximum amount and incremental salary steps between both endpoints. County policies permit hiring managers to consider paying new county employees above step 1 in certain circumstances, such as when the employee possesses unusual qualifications, including relevant education, experience, and training, that are above the minimum required qualifications of the classification. As shown in Table 6, the four counties established the starting salary at the minimum step for 42 of 57 employees we reviewed. We also found that, depending upon the education, previous experience, and recruiting challenges associated with the candidates, 15 of the 57 new employees were hired at higher than the base step. Of these 15 employees hired above their respective minimum rates, seven were men and eight were women. Table 6 shows that women were hired at minimum salary rates in 30, or 79 percent, of the 38 cases we reviewed, and men were hired at minimum salary rates for 12, or 63 percent, of the 19 cases we reviewed.

| GENDER | COUNTIES' NEW HIRES WHO STARTED | TOTAL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT MINIMUM SALARY STEP | ABOVE MINIMUM SALARY STEP | ||||||

| NUMBER | PERCENTAGE OF GENDER | NUMBER | PERCENTAGE OF GENDER | ||||

| Female | 30 | 79% | 8 | 21% | 38 | ||

| Male | 12 | 63% | 7 | 37% | 19 | ||

| Totals | 42 | 15 | 57 | ||||

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of salary decisions for newly hired employees at Fresno, Los Angeles, Orange, and Santa Clara counties appointed to positions with a salary-step schedule.

To understand whether counties were consistently assigning the minimum rate to both men and women based on their qualifications and experience, we made further inquiries for some of the 42 employees where the counties assigned the minimum pay. Specifically, we identified 13 instances in which it initially appeared, in our view, that the new employees’ professional background and educational experience exceeded the minimum requirements for the classification.

When evaluating county decisions to pay only the minimum amount, we reviewed five salary decisions (all female employees) in Fresno County, two salary decisions (one male employee and one female employee) in Orange County, three decisions (one male employee and two female employees) in Los Angeles County, and three decisions (one male and two female employees) in Santa Clara County. In response to our inquiries about these 13 salary decisions, county officials from all four counties provided various explanations for establishing the employees’ pay at the minimum rates, citing such factors as the lack of difficulty in recruiting for the positions in question or the lack of support for higher starting salaries given policies to pay at the minimum rate. For example, a female employee at Santa Clara County was hired for a clinical nurse II position and the minimum requirement for the position was that the successful candidate possess at least one year of acute care experience and possess a valid California registered nurse license. The individual who was hired in this case seemingly exceeded these requirements by possessing 11 years of experience as an operating room nurse, which was noted in her application materials. The county justified the minimum salary level for the employee by stating that the county received many applications for this classification from candidates who met or exceeded the minimum qualifications; therefore, the county did not consider this applicant’s years of experience to constitute “unusual qualifications” warranting a salary above the minimum. We confirmed that there were three other eligible candidates on the certified eligibility list for this nursing position, making them all competitive for the position.

At Fresno County, we identified five female employees who appeared to have qualifications above the position’s minimum requirements. In answer to our inquiry, a county personnel analyst indicated that department heads do not routinely ask for a higher pay rate for new hires (regardless of qualifications), as they have been instructed to offer the minimum salary rate. Further, the Fresno official noted that it is not unusual for individuals who far exceed the minimum qualifications to apply for and accept entry-level positions at the minimum salary rate. When we followed up with the remaining two counties—Orange and Los Angeles—county officials often indicated that applicants for the positions in question were not difficult to recruit.

Although paying the minimum rate for new county employees was common in the selection of employee records we reviewed, 15 new employees (seven men and eight women) received pay rates above the minimum amounts for their particular classifications. As we did in our review of employees who were paid at the minimum amount, we attempted to determine whether counties were consistently providing higher pay to these male and female employees based on their education and other job-related professional experience. We reviewed records for the 15 employees who were paid above the minimum rate: six in Orange County, five in Santa Clara County, with Los Angeles County accounting for the remaining four employees. We saw no consistent pattern among these 15 employees—their associated classifications included attorneys and information technology workers, among others. For 12 of the 15 pay decisions, county officials were able to show us the internal requests and approvals from county human resources managers authorizing the higher pay amounts. In the three other cases, Orange County could not locate the support and approval for the higher pay. For 11 of 12 justifications and approvals, counties cited that the reason for the higher starting salary amounts was the hiring manager’s conclusion that the candidate’s professional or educational background was particularly impressive and relevant to the position.

For example, Los Angeles County hired a male information technology specialist I above step 1. The county justified the decision by citing the employee’s extraordinary education and work experience in a related field. In another instance, Santa Clara County hired a female regional planner at salary step 3 and justified the decision based on the candidate’s relevant master’s and bachelor’s degrees in architecture and urban planning, along with her nearly five years of relevant experience. We reviewed the two employees’ resumes and concluded that their experience exceeded the position’s minimum qualifications. We also noted that, for three of the six employees who Orange County brought in above the minimum rate, the county cited the employees’ merit, experience, education, and recruiting difficulties on their salary justifications and these decisions were consistent with their county policies. For example, the county justified its hiring of a surveyor above the minimum rate by describing the candidate’s prior work experience in the field and discussed the difficulty in finding well-qualified candidates. The county stated that it had recently made offers of employment to three candidates for four vacant positions, all of whom declined the offer due to the increased demand for surveyors in the region.

A less common reason why counties paid new employees above the minimum rate was the belief that the candidate would not accept a lower amount, a situation that occurred for two of the 12 cases we reviewed. For example, the higher salary step request from Orange County’s Health Care Agency cited the likelihood that a candidate for a clinical social worker II position would reject the employment offer if she was not hired at $31.28 per hour (the normal hiring rate is $25.17 for the position).

Despite counties’ policies allowing hiring managers to use discretion when making salary decisions, we did not see any instances of sex-based discrimination in the counties’ salary-setting decisions for the new employees that we reviewed. Salary decisions were often based on the employees’ qualifications and experience; however, we also noted that what an employee earns is not always dependent on their qualifications. Some of the counties indicated that many of the positions that we were questioning were not difficult to recruit for even though the candidates exceeded the job’s minimum qualifications.

Female Employees in Our Selection Were Less Likely to Receive Salaries Above the Midpoints of the Salary Ranges for Positions With Negotiated Salaries

The data in our selection show that women were less likely than men to receive starting salaries above the midpoints of broad-range salary schedules. Of the 240 salary decisions we evaluated, 54 involved employees who were either newly employed or who had transferred or promoted into a county classification for which the salary amount fell within a broad range without any incremental salary steps. For some county employees in this group, the salary amount could be the result of negotiations and thus could not be explained by a particular county policy, such as those that require a certain percentage increase over prior pay upon an existing employee’s promotion or transfer. Neither federal nor state laws expressly require that counties document how they determine salary amounts for those that are negotiated and the four counties similarly do not require such documentation. The difference between the minimum and maximum salary in these broad-range positions can be large. For example, as of April 2015, the broad-range salary for the position of chief deputy director at the Los Angeles County’s Department of Public Works has a span of $96,744, with the minimum salary of $188,370 and a maximum capped at $285,114. Additionally, the salary range for the chief child psychiatrist position in Fresno County spanned $127,608, with a minimum salary of $122,408 and a maximum salary of $250,016. We analyzed how often the 54 employees (30 men and 24 women) received salary amounts above the midpoint of the salary range.

Based on our review of 39 employees receiving salaries above the midpoint, 28 were from Orange and Santa Clara counties. The data show that women were less likely than men to obtain a salary above the midpoint. Specifically, 24, or 80 percent, of 30 male employees and 15, or 63 percent, of 24 female employees successfully negotiated or otherwise received salaries above the midpoint of the salary range. We attempted to identify any trends in the types of positions in our review where employees entered either above or below the salary midpoint, but none emerged. Employees who were attorneys or who were employed as the chief, director, or administrative manager of some county function had salaries that were both above and below the salary midpoints for their positions.

All Four Counties Had Policies That Considered Prior Salaries When County Employees Transferred or Promoted Into New County Classifications

Some advocates for greater pay equity argue that an employer’s consideration of an employee’s prior salary from a different classification can perpetuate pay disparities, noting that women have historically earned less than their male counterparts. Although state law does not expressly prohibit an employer from requesting or considering a candidate’s salary background, in 2015 California’s Legislature approved a bill that would have prohibited employers from seeking a candidate’s salary history. That bill was vetoed and a similar bill is now pending. In federal government, the U.S. Department of Personnel Management recently advised federal hiring managers against using an employee’s prior salary as the sole basis for determining current pay, noting that such a practice could hurt those who are returning to the workforce after an extended absence.

The four counties we visited each had salary-setting policies that expressly require consideration of prior pay when existing county employees transfer or promote into a different county classification. Some of the counties we visited stated that having such policies helps them to retain existing employees, to promote their upward mobility, and to ensure that employees are not penalized financially when changing classifications within the county. For example, when explaining Los Angeles County’s perspective, the compensation division manager stated that not having such a rule and requiring all employees to promote or transfer at the minimum salary rate of the new classification would likely cause some employees (men and women alike) to incur pay cuts when they change positions because the salary ranges between employees’ previous and current county classifications could overlap. To prevent such occurrences, each of the four counties we visited had variations of a policy ensuring that county employees earn at least the same amount, if not more, when they transfer or promote into a different county position.

We reviewed 180 salary-setting decisions made for fiscal years 2013–14 through 2014–15 for employees appointed to positions with a salary-step payment structure. We noted that for 123, or 68 percent, of those decisions, the employees had either transferred or been promoted into a different county classification. As shown in Table 7, for 100, or 81 percent, of the 123 salary-setting decisions that resulted in starting pay above the minimum salary step, we found that 80 percent of women and 83 percent of men started above the minimum salary step.

| GENDER | NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES WHO STARTED A NEW CLASSIFICATION | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT THE MINIMUM SALARY STEP | ABOVE THE MINIMUM SALARY STEP | ||

| Female | 14 | 55 | 69 |

| Male | 9 | 45 | 54 |

| TOTALS | 23 | 100 | 123 |

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of salary decisions for employees at Fresno, Los Angeles, Orange, and Santa Clara counties who are paid under a salary-step schedule.

When employees change classifications as a result of a transfer, and not a promotion, the four counties’ policies require employees to maintain their existing pay levels, which can also result in county employees entering their new classifications at a pay rate that is above the minimum amount. For example, at Santa Clara County, we found two individuals who began work on the same day as account clerk IIs at the county’s Social Services Agency, but they started with significantly different salaries. One individual—a woman who was also a new county employee—was paid at the minimum salary rate (or hiring rate) of $41,456 per year. The second employee (also a woman) had transferred from within the county and, due to earning a higher salary in her previous classification as an office specialist III, began work as an account clerk II earning $50,019 per year (salary step 5). Although both employees had the same amount of time in the new position, the two employees’ salaries were different by more than 20 percent. Clearly, the employees’ gender was not the cause of the disparity since both employees were women; rather, the cause was the county’s policy of using the existing county employee’s prior salary when establishing her current pay.

Such county pay policies, while beneficial to existing county employees, effectively reward the employee for prior service with the county (a form of seniority-based pay) and this additional pay above the minimum amount following a promotion or transfer may or may not bear any relationship to that employee’s actual ability to perform the work relative to others in the same classification. Put another way, in our previous example, it is entirely possible that the new county employee earning the minimum $41,456 per year is just as productive in performing the work of an account clerk II as the county veteran earning $50,019 per year.

During our audit, we attempted to understand whether seniority-based pay systems needed to be based on a particular classification (or group of similarly related classifications) or whether they could be more broadly applied to prior service with the employer, as appears to be the case with the four counties we reviewed. State and federal laws are not that specific or prescriptive in terms of how seniority-based pay systems must work. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has advised that employers who rely on a seniority system as a defense must be able to demonstrate that the seniority-based system was adopted without discriminatory intent, has predetermined criteria for measuring seniority that has been communicated and is consistently applied to all employees, and is, in fact, the entire basis for the difference in compensation. We observed that counties had described in local ordinances or countywide personnel rules how salary amounts are to be calculated when existing employees change classifications. Further, as discussed earlier, we saw evidence that both male and female county employees benefited from these pay policies in practice.

Nevertheless, employers who use prior salary when establishing a new employee’s pay may risk further perpetuating pay inequities. The federal courts are split on whether an employee’s prior salary can ever serve as the sole basis for a pay disparity. The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which is the appeals court that California must follow, has held that the Federal Pay Act does not impose a strict prohibition against the use of prior salary as one of several factors an employer may use to arrive at a employee’s salary and that it may constitute a legitimate business reason for a pay differential. Other circuit courts, however, have taken a different position. In December 2015, the federal District Court for the Eastern Division of California held that an employer’s reliance on an employee’s prior salary as the sole basis for a salary differential conflicts with the Federal Pay Act, stating that “a pay structure based exclusively on prior wages is so inherently fraught with the risk that it will perpetuate a discriminatory wage disparity that it cannot stand, even if motivated by a legitimate business purpose.” This ruling allowed a female plaintiff to continue her litigation against a county superintendent of schools.

For the Few Cases We Identified, Counties Often Found That Gender-Based Pay Equity Complaints Lacked Merit, but the Frequency of Such Complaint Filings Is Unclear

Our audit could not quantify definitively how often the four counties we visited received complaints pertaining to pay or promotional disparities based on gender. The counties we visited do not specifically track gender-based wage and promotional complaints, and neither federal nor state law currently requires that they specifically track this information. All four counties we visited had developed their own local policies to promote equal employment opportunities and to prevent and respond to alleged instances of discrimination in the workplace. These local policies frequently encouraged county employees to file complaints—with their own county department or with a designated county office—when alerted to potential violations of county equal pay policies.

However, the counties’ processes for recording and tracking employee complaints were not always centralized, making it difficult to determine the universe of equal-pay complaints that were filed by county employees. Except for Los Angeles County, in three of the four counties we visited, local officials provided us with various lists of complaints, each covering different time periods or types of complaints, or they were maintained by different county officials. Further, we noted that the counties we visited do not label complaints at a level of detail that would allow for the easy identification of those involving potential violations of equal-pay laws. County complaint forms themselves often included only a checkbox for the complainant to mark for the protected characteristic (such as “gender” or “sex”), while an open-text field provided the complainant with an opportunity to provide more specifics on the nature of the complaint (that is, whether the complaint was wage-related or involved some other concern). As a result, we used our professional judgment to identify complaints that appeared to pertain to gender equity issues with respect to wages or promotional opportunity, and then review how the counties investigated and resolved those complaints.

Table 8 provides information on the total number of complaints that each county received from fiscal years 2010–11 through 2014–15 regardless of the protected characteristic (such as gender, age, ethnicity, etc.). The table also shows that of these total complaints, relatively few complaints appeared to us to allege gender-based discrimination regarding wages or promotional advancement. When searching for these types of complaints, we filtered the counties’ complaint logs based on sex or gender, and when possible, searched for key words such as “wage” and “salary” within the narrative section describing the complaint. In Los Angeles County we identified 21 pertaining to wage and promotional discrimination based on sex or gender. We identified these 21 complaints (which Los Angeles County had received from fiscal years 2011–12 through 2014–15) after performing keyword searches on more than 12,000 complaints. In the other three counties, we could only find seven or fewer complaints that appeared relevant to our audit. However, limitations with the data made it difficult to definitively quantify how often county employees filed gender-based pay equity complaints with their employers, so the actual number of these types of complaints filed may be higher. Nevertheless, of the 36 complaints we identified in Table 8 that appeared to us to allege gender-based discrimination regarding wages or promotional advancement, 10 complaints are still under investigation, 25 complaints were not substantiated, and one was substantiated; however, this complaint is still in litigation and therefore, we are not able to discuss the specifics of the allegation.

| FRESNO COUNTY (JULY 2010–JUNE 2015) |

LOS ANGELES COUNTY (JULY 2011–JUNE 2015) |

ORANGE COUNTY (APRIL 2011–JUNE 2015) |

SANTA CLARA COUNTY (JULY 2010–APRIL 2015) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of complaints identified on complaint logs we reviewed | 368 | 12,463 | 416 | 1,427 | |

| Auditor-identified cases pertaining to wage or promotional discrimination (based on gender) | 4 | 21* | 4 | 7 | |

| Female complainant | 1 | 11 | 4 | 5 | |

| Male complainant | 1 | 11 | 4 | 5 | |

| Outcomes of complaint investigations | |||||

| Complaint Still Under Investigation | 0 of 4 | 10 of 21 | 0 of 4 | 0 of 7 | |

| Complaint Not Substantiated | 4 of 4 | 11 of 21 | 4 of 4 | 6 of 7 | |

| Complaint Substantiated | 0 of 4 | 0 of 21 | 0 of 4 | 1 of 7 | |

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of county-provided complaint logs and review of source documents for cases we identified as pertaining to gender-based wage or promotional discrimination at the counties of Fresno, Los Angeles, Orange, and Santa Clara.

* In Los Angeles County, we identified 21 complaints that appeared relevant to our audit. To provide context, we note that Los Angeles County recorded that 5,195, or 41 percent, of more than 12,463 total complaints pertained to discrimination, of which 2,182 contained enough information to warrant review by the County Equity Investigations Unit. Of the 2,182 complaints that the county designated as warranting investigations, 401 related to gender.

The most common type of complaint we identified was one in which a county employee alleged that he or she was denied a promotion based on his or her sex, a complaint that occurred in 31 of the 36 complaints we reviewed. For example, a Fresno County employee claimed discrimination based on sex, race, color, and national origin when applying for a new position. The complainant alleged that members of the opposite sex who had less experience were hired. In response, Fresno County’s legal counsel compiled a report detailing the complaint and concluded that it was unsubstantiated. The report documented how many applicants were male and female, as well as the ethnicity and the ranking of the applicants. The report also informed the complainant of the right to file an appeal with the Department of Fair Employment and Housing or the EEOC. Finally, the legal counsel’s report noted that the complainant was subsequently hired into the position.