Introduction

Background

The federal government provides grant funding to states to provide children with disabilities a free and appropriate public education and has established, through the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), the requirements for the state programs that it funds. In accordance with IDEA, these programs include two main components: special education and related services. Special education is specially designed instruction, which is provided at no cost to the parents, to meet the needs of a student with a disability. Related services include transportation and other developmental, corrective, and supportive services that are required to help students with disabilities benefit from special education. These related services can include mental health services, such as psychological services and counseling services. This audit is focused on the mental health services provided to students within California's special education program and changes to state law that affected how these services are provided to students.

Organization of the State’s Special Education Program

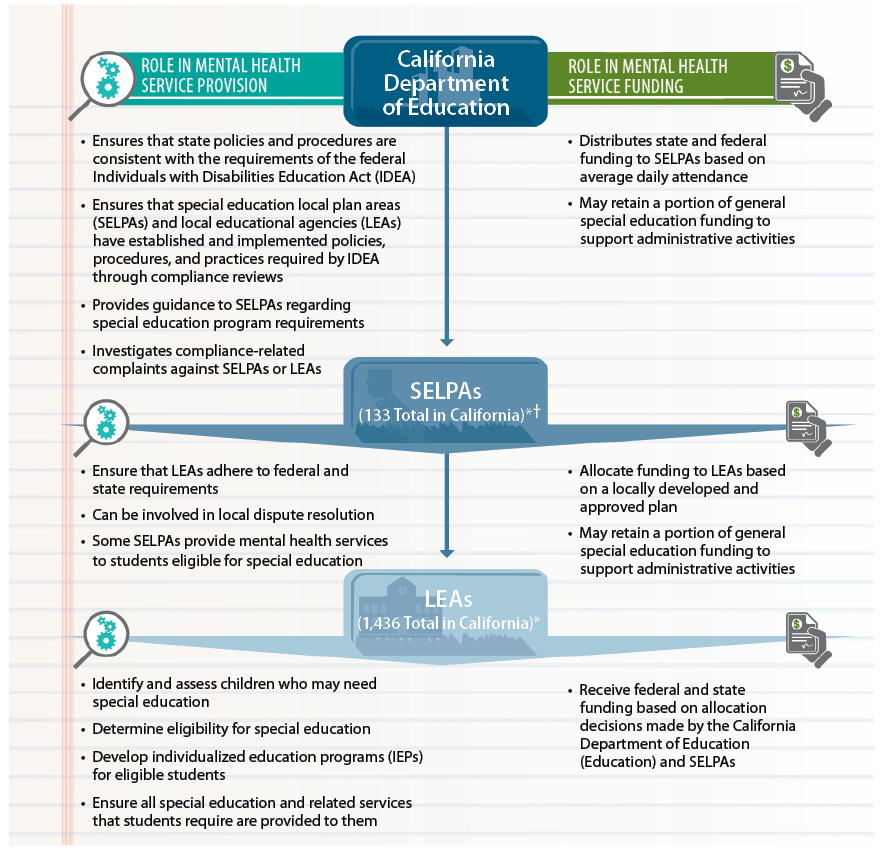

The California Department of Education (Education) oversees and supervises California’s public education system under the direction of the superintendent of public instruction. The State Board of Education (Board) is California’s state educational agency for elementary and secondary education and is responsible for ensuring that the State meets the requirements that IDEA assigns to state educational agencies. The Board fulfills this responsibility through Education. In this role, Education ensures that California’s special education program meets federal requirements and collects and reports data to the public about the special education program, among other responsibilities.

As shown in Figure 1, Education investigates complaints, performs compliance reviews, and distributes federal and state funds to special education local plan areas (SELPAs). SELPAs are single school districts, multiple school districts, or a district joined with the county office of education to provide special education and related services. Each SELPA comprises one or more local educational agencies (LEAs), a category in California consisting of school districts and some county offices of education and charter schools. LEAs are responsible for ensuring that students receive their required special education and related services.

Figure 1

Organization of Special Education in California

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of Title 20 United States Code, sections 1411, 1412, 1413, and 1415; Title 34 Code of Federal Regulations, Section 300.151; California Education Code, sections 56836.01, 56836.02, 56836.07, and 56836.08; Education’s website; interviews with staff at selected SELPAs.

* The total number reported is as of October 2015, although this number will vary over time.

† The number of SELPAs includes state agencies (state‑operated programs) that are identified as SELPAs for administrative purposes.

Members of an Individualized Education Program Team

- The parents or guardians of a child with a disability.

- At least one of the child’s regular education teachers.

- At least one of the child’s special education teachers or special education providers.

- A representative of the local educational agency (LEA) who is qualified to provide or supervise special education and who knows about the resources the LEA has available to provide to students.

- An individual who can interpret the instructional implications of student evaluations.

- Other individuals who have knowledge or expertise regarding the child, at the discretion of the parent or agency.

- The child, when appropriate.

Sources: Title 20 United States Code, Section 1414.

Federal law requires LEAs to evaluate children in all

areas of suspected disability to determine whether they are eligible for special education and related services, including mental health services, and the nature of the student’s educational needs. To be eligible, a student must be found to have a disability and require special education and related services as a result of that disability. For every student who is eligible, LEAs are required to develop an individualized education program (IEP). The IEP is a core element of IDEA and, as such, it is integral to the purpose of IDEA, which is to ensure that a free and appropriate public education is available to students with disabilities. The IEP must describe, among other things, the effects of the student’s disability on educational performance, the student’s educational goals, and the special education and related services the student will receive to assist in his or her educational progress. An IEP team develops the IEP for each student. As shown in the text box, the IEP team includes the student’s parents or guardians and teachers, as well as other representatives from the LEA. According to data maintained by Education, in the 2014–15 school year nearly 14 percent of those students with an IEP received a mental health service as part of the IEP.

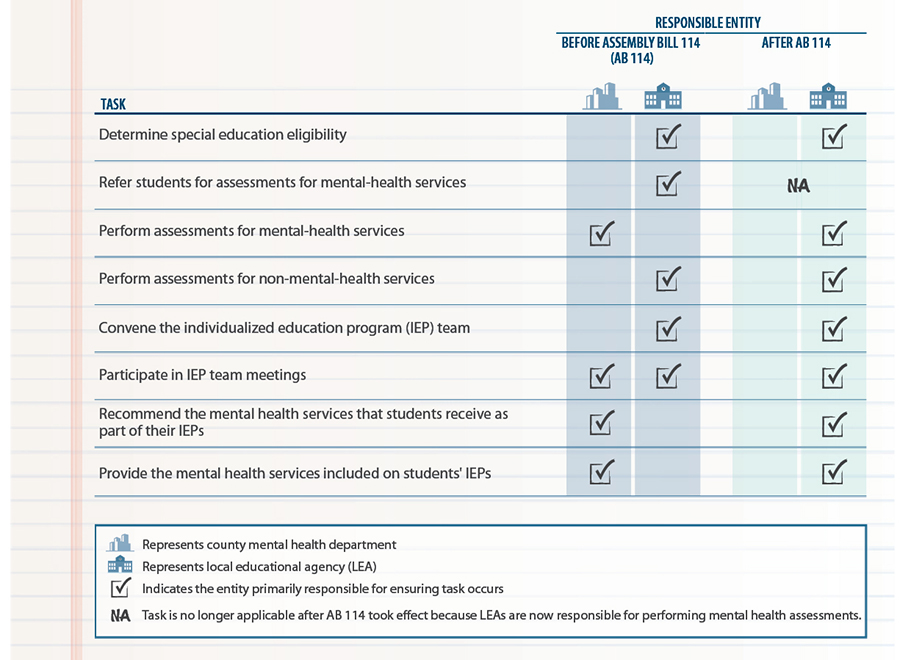

The Passage of Assembly Bill 114

Through June 2011 state law required county mental health departments to conduct an assessment of the social and emotional status of a student and recommend the related services required to help the student.Through June 2011 state law required county mental health departments to conduct an assessment of the social and emotional status of a student and recommend the related services required to help the student.4 After the county representatives presented their recommended services to the IEP team, the representatives of the LEA who were a part of the IEP team were required to adopt the county recommendation as their own after reviewing and discussing it. The county was also required to provide the mental health services that were included in a student’s IEP.

In June 2011 the governor signed into law Assembly Bill 114 (AB 114) (Chapter 43, Statutes of 2011), which changed how mental health services become part of an IEP and the parties responsible for providing those services. The governor's proposal to make LEAs responsible for providing the mental health services in IEPs stated that doing so would lead to greater cost containment and create a stronger connection between services and student educational outcomes. The portions of AB 114 relevant to special education took effect in July 2011 and nullified the portions of state law that made the counties responsible for conducting assessments, recommending mental health services to be included on a student's IEP, and providing those services. This change made LEAs responsible for conducting student mental health assessments, presenting the assessments to IEP teams, and providing all services in IEPs. Figure 2 shows the responsibilities that LEAs and county mental health departments had before and after AB 114 took effect.

Figure 2

Key Responsibilities Under State Special Education Law Before and After Assembly Bill 114 Took Effect

Education has published guidance to assist LEAs in understanding the options available for mental health services since AB 114 took effect. This guidance states that an LEA can hire mental health professionals, such as social workers and psychologists, and provide services through these staff. State regulations establish minimum qualifications for individuals who provide mental health services that vary depending on the type of services the individual provides. An LEA may also contract out some or all of these duties to a community mental health provider, another qualified professional, or the county mental health department.

Funding for Special Education and Mental Health Services

In several of the years preceding AB 114, counties received state funds to provide mental health services to students with IEPs. Under this model, counties could also submit reimbursement claims to the State for additional costs, with some limitations, that they incurred related to providing the mental health services included in a student’s IEP. In October 2010, through a line-item veto, the governor struck the funding appropriated to reimburse counties for providing mental health services included in IEPs during previous years. When he vetoed the funding, the governor stated that it was part of his effort to maintain a prudent General Fund reserve. This action suspended the state mandate for county mental health departments to provide mental health services included in IEPs.

After the reimbursement model was suspended, the Legislature allocated a specific amount of funding to Education to distribute directly to SELPAs for the provision of mental health services. Education also reminded LEAs that, due to the suspended mandate, under federal law they were responsible for providing the mental health services included in student IEPs. Later in that fiscal year, the Legislature appropriated additional funding to assist LEAs in providing these services. This funding was meant to cover the costs that LEAs incurred for mental health services in fiscal year 2010–11 while the state mandate to provide mental health services was suspended.

Since AB 114 took effect in July 2011, funds from federal and state sources have supported the provision of mental health services to students with IEPs. Education receives these funds and distributes them to SELPAs mostly based on average daily attendance.5 Therefore, SELPAs with LEAs that have a higher average daily attendance receive more funding than those with lower average daily attendance. Education designates a portion of California’s federal special education funding specifically for the purpose of providing mental health services to special education students. In addition, the State has dedicated part of its own special education funding for the same purpose. Funds from these two funding sources are considered restricted and can be used only for mental health services called for in students’ IEPs (mental health funding). Education distributes this mental health funding to SELPAs, which then allocate it to their LEAs. In addition, Education distributes general special education funding (special education funding) to SELPAs. This special education funding is not limited to any one purpose within the special education program. In other words, SELPAs and LEAs are free to use this funding to pay for mental health services for students if they choose, but they may also use it for other purposes related to special education. Finally, LEAs can also use their unrestricted general funding to pay for mental health services that special education students require, or LEAs may use this funding for other activities beyond their special education program.

In addition to these sources of funding, LEAs have access to another funding source. For all students who are eligible for the California Medical Assistance Program (Medi-Cal), LEAs can avail themselves of the LEA Medi-Cal Billing Option program through the California Department of Health Care Services (Health Care Services). This program provides federal reimbursements for 50 percent of the allowable costs of certain direct services to students, including some mental health services.

Mental Health Services Available Through Another Program

Students may also receive mental health services through the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) program. This program can provide services for children who are eligible for full-scope Medi-Cal benefits.6 According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, EPSDT is designed to ensure that children receive early detection and care, so that health problems are averted or diagnosed and treated as early as possible. The federal program requires that all medically necessary screening and treatment services be provided to individuals under the age of 21 years. These services include screening to detect physical and mental health conditions and any related treatment that would be required to address these conditions. Students do not need to be eligible for special education to receive mental health services through the EPSDT program.

Depending on a child’s eligibility for special education and the dedicated mental health programs that the State and counties offer, more than one entity may be mandated to provide a child with mental health services. In contrast to the special education eligibility requirements, eligibility for Medi-Cal services for low-income families and individuals under 21 is based on medical need rather than educational need. Therefore, children who are eligible for both the special education program and one or more of California’s mental health programs may receive mental health services from either their county mental health department, the LEA at which they attend school, or both.

SELPAs and LEAs Selected for Review on this Audit

Our audit included four SELPAs and LEAs, as well as information we obtained from county mental health departments where the SELPAs we reviewed were located. To select the SELPAs we would review, we considered a variety of information, including the number of LEAs in the SELPA, the number of compliance complaints on record at Education for each SELPA, the number of mental health services offered by the LEAs within each SELPA over time, information related to the use of mental health funding, and the geographic location of the SELPA in the State. At each SELPA with multiple LEAs, we selected the LEA within the SELPA that provided the greatest total number of mental health services between 2010 and 2013, as indicated in its reports to Education. Table 1 shows the SELPAs we selected and their corresponding LEAs and counties.

Table 1

Special Education Local Plan Areas and Local Educational Agencies Selected for Review

| SPECIAL EDUCATION LOCAL PLAN AREA (SELPA) | CORRESPONDING LOCAL EDUCATIONAL AGENCY (LEA) |

CORRESPONDING COUNTY |

|---|---|---|

Source: California State Auditor’s analysis of information from the California Department of Education website.

Scope and Methodology

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee (audit committee) directed the California State Auditor to review the State’s use of mental health funds and provision of mental health services to students. Specifically, we were directed to review the effects of AB 114. Table 2 lists the objectives that the audit committee approved and the methods used to address those objectives.

| Audit Objective | Method |

|---|---|

| 1. Review and evaluate the laws, rules, and regulations significant to the audit objectives. |

Reviewed relevant laws, rules, regulations and other background materials related to the provision of mental health services both before and after they were affected by Assembly Bill 114 (AB 114). |

2. Review and evaluate the California Department of Education’s (Education) responsibilities with respect to the oversight and administration of federal and state special education law as it relates to mental health issues. Determine whether the State is complying with relevant laws, regulations, and policies in monitoring funding streams and outcomes for students with mental health issues. |

Interviewed staff at Education and reviewed documents to determine what oversight activities Education performs. Mental health services are one form of related services that must be provided to students with disabilities when such services are required for the students to benefit from special education. Federal law does not specify how the State will meet the requirement to provide mental health services but instead requires states to provide special education and related services to children with disabilities. Therefore, we reviewed Education’s compliance with these more general requirements. We determined that the federal government has accepted Education’s plan for general oversight of the special education program and that Education is performing the key tasks that it outlines in that plan. For each of the special education local plan areas (SELPAs) visited under objective 4 and each of the local educational agencies (LEAs) visited under objective 8, reviewed the documentation that the SELPA or LEA submitted to Education to show that the entity met the federal maintenance of effort requirements. We determined that Education had ensured the entities we reviewed met the federal requirement to maintain the same level of funding from one year to the next. Reviewed Education’s activity related to data collection and reporting and compared it to key federal and state requirements. We determined that Education complies with these requirements. |

| 3. Review and evaluate the impact on the number of students with disabilities placed in residential programs both in-state and out-of-state, before and after the enactment of AB 114. To the extent possible, provide information on the reasons students are placed in these programs, and determine whether those reasons have changed over a five-year period. |

Analyzed summary data regarding the number of students who received residential treatment services before and after AB 114 took effect from 2010–11 through 2014–15. Interviewed staff at Education and the SELPAs and LEAs we reviewed to determine their perspective on the trends in residential placements over this five‑year period. At each SELPA visited under objective 4, selected students who were in residential treatment in school year 2010–11 and reviewed subsequent individualized education programs (IEPs) for each student to determine whether the reasons for placement changed, whether the district documented the consideration of potential harmful effects of placement, and whether the district documented a rationale for placing the student into a more restrictive environment. At three SELPAs, we selected five students apiece for review. At the other SELPA, we selected all of the students who met our criteria, which resulted in us reviewing three students. Interviewed staff at LEAs to determine reasons for residential placement when those reasons were not documented in a student’s IEP document. |

| 4. From a selection of at least four SELPAs, review and assess the complaint process and determine whether each SELPA’s process is effective, including whether the SELPA makes parents, guardians, and students aware of the complaint process. Further, for a selection of complaints from each of the SELPAs, determine whether the process for addressing complaints was followed. |

As shown in Table 1, selected Mt. Diablo Unified School District (Mt. Diablo), Long Beach Unified School District (Long Beach), Riverside County Special Education Local Plan Area (Riverside), and South East Consortium for Special Education (South East). Reviewed federal and state laws and regulations to determine what information should be provided to parents, guardians, and students regarding complaint processes, and how frequently. Interviewed SELPA staff to determine the entities’ procedures for providing notice of complaint processes to parents. Evaluated up to three IEP documents apiece for 15 students at each SELPA and determined whether the IEP documents showed that parents, guardians, or the students were offered the procedural safeguard notice. Obtained seven complaint records pertaining to each SELPA, and evaluated whether the appropriate processes were followed. |

| 5. For a five-year period, using the SELPAs identified in objective 4, provide the following information, to the extent possible, disaggregated by students for whom an IEP identifies as emotionally disturbed, students whose IEP may also call for mental health services, and students receiving mental health services who qualify or do not qualify for the California Medical Assistance Program (Medi‑Cal) services: | |

a. Compare the number of students each SELPA served under Assembly Bill 3632 (AB 3632) to the number served under AB 114. |

Obtained data from Education and analyzed the number of students with mental health services in their IEP in years 2010–11 through 2014–15 at the four SELPAs identified under objective 4. Using data from Education and data from the California Department of Health Care Services, identified the number of students with an IEP that included mental health services, the number who were eligible for Medi‑Cal, and the number whose IEP identified them as emotionally disturbed, by year, and the number at each SELPA visited. This information is presented in the Appendix of this report. Statewide, compared the number of students with mental health services in their IEP to the total number of students with IEPs. Calculated the rate at which each SELPA continued to provide mental health services to students from one year to the next before and after AB 114 took effect. |

b. Determine whether the type and frequency of service, and the providers of services, changed under the transition from AB 3632 to AB 114. |

Obtained data from Education and determined the following:

|

c. For a selection of students served under AB 3632, determine whether their IEPs were changed as the result of the SELPAs’ transition to AB 114. To the extent possible, assess whether the IEP changes were allowable and the reason was documented. |

Selected 15 students from each SELPA identified under objective 4 who received at least one mental health service through their 2010–11 IEP. Reviewed subsequent IEPs for these students to determine if the mental health service levels changed and whether the reasons for those changes were recorded in the IEP document. Interviewed staff and reviewed other available information at the LEAs where these students attended school to determine the reasons for changes to services when those reasons were not recorded in the students’ IEP documents. |

| 6. To the extent possible, determine whether changes in treatment were made by service providers as a result of the transition from the AB 3632 to the AB 114 process.. |

Identified a staff member at each of the LEAs reviewed under objective 8 who provided mental health services before and after AB 114 became effective. Interviewed those staff members to determine the factors that influence treatment decisions and whether the transition to AB 114 affected mental health treatment. Determined that, according to the staff we interviewed, methods of treatment were not changed as a result of AB 114. |

| 7. Determine whether the State has a mechanism in place to evaluate the transition from AB 3632 to AB 114. |

Interviewed staff at Education to determine whether Education completed an evaluation of the transition to AB 114 and whether they were aware of any other transition evaluations. According to Education’s associate director of special education, Education analyzed the status of the transition to provide policy guidance and support to LEAs though the AB 114 Workgroup and devoted extra resources to track and analyze data, monitor complaints, develop and vet policy guidance, and administer funding. We reviewed materials from Education’s website that show it performed some of these activities. However, we saw no evidence that Education performed an evaluation to determine whether the transition was effective. The associate director noted that the 2011 budget bill did not direct Education to perform this type of analysis and that the Legislature did not provide Education funding for one. Reviewed AB 114 to determine whether it contains a requirement to evaluate the transition in mental health service provision and determined that it does not. |

| 8. Identify state and federal funding sources for mental health services for students with disabilities for the past five fiscal years. Further, for the SELPAs selected for objective 4 and from a selection of LEAs, compare their mental health budgets to their costs. Determine the source of funds the SELPAs used to pay for any excess mental health costs. |

Reviewed Education’s summary of funding sources for mental health services and verified that the information in that summary matched the annual budget act for fiscal years 2010–11 through 2014–15. Identified any additional funding sources through our review of SELPA and LEA budgets, revenues, and expenditures as described below. Reviewed California State Controller reports regarding the amounts counties claimed in reimbursements for their fiscal year 2010–11 mental health costs. Obtained financial information from the SELPAs we visited in objective 4 and a selection of one LEA at each SELPA as shown in Table 1. Because two of the SELPAs we reviewed, Mt. Diablo and Long Beach, are single-LEA SELPAs, we reviewed a total of six entities’ fiscal records. Compared the budgeted expenditures, actual revenue, and actual expenditures that each entity recorded for its restricted mental health funding for fiscal years 2010–11 through 2014–15. Determined that Riverside and South East did not spend more than they received in mental health funding in the fiscal years we reviewed. Interviewed staff at each LEA to determine how the LEA covers any excess costs to provide mental health services through an IEP. Interviewed program and financial staff at each LEA and SELPA to determine how each entity used available Medi‑Cal funding to pay for services. |

| 9. For the selection of LEAs identified in objective 8, review and assess the following: | |

a. Each LEA’s process for hiring mental health services staff, including how each LEA ensures the staff are qualified. In addition, for LEAs that contract for services, determine the qualifications of the mental health services providers, identify who the providers are, and determine who is responsible for contracting these services. To the extent possible, compare the qualifications of licensed and nonlicensed LEA employees and contracted services providers (that is, nurses, therapists, psychologists, etc.). |

Reviewed state regulations to determine what qualifications are required to provide mental health services to students. Interviewed LEA staff to determine LEA procedures for hiring mental health service providers and for contracting for mental health services, including whether those procedures include verification that staff and contracted personnel meet the requirements in state regulations for providing specific mental health services. At each of the four LEAs we reviewed under objective 8, judgmentally selected five staff mental health providers and five contracted mental health personnel. Interviewed SELPA or LEA staff to determine what specific mental health services each selected staff or contracted personnel member provided to students. Determined whether the selected providers met the qualifications required by state regulations. Compared the qualifications of selected mental health staff to those of contracted mental health personnel. |

b. Review and assess each LEA’s process for identifying students needing a special education assessment for mental health services, including the criteria for denying an assessment for mental health services. |

Reviewed relevant federal and state laws and regulations related to activities for identifying students who require assessment, known as child find activities. Also reviewed child find policies and procedures we identified through other states’ education departments and online research to identify best practices related to child find. Obtained and reviewed the child find policies for each SELPA and LEA we reviewed and compared those policies to the relevant laws and regulations to ensure the policies contained key activities. Also reviewed the policies of each SELPA and LEA we visited to identify whether they included any best practices that we had found. Interviewed staff at the SELPAs and LEAs we reviewed and obtained documentation of the activities they perform to demonstrate compliance with their stated policies and procedures. Reviewed federal regulations to determine the requirements for denying special education assessments, including the required components of notice of a denial of an assessment. Interviewed staff at each LEA to determine whether the LEAs had denied a mental health assessment in school year 2014–15. Determined that among our four selected LEAs, two LEAs, East Side Union High School District and Murrieta Valley Unified School District, had not denied any mental health assessments in 2014–15. We reviewed the reason why Long Beach would deny assessments and found that reason consistent with federal law. Determined that Mt. Diablo had no specific criteria for denying assessment requests. Therefore, we reviewed a judgmental selection of five of Mt. Diablo’s denials from 2014–15 and determined that all of the denials we reviewed complied with the key components of the federal requirements. |

c. Review and assess how each LEA measures and tracks the outcomes for students receiving mental health services. |

Identified the key outcome indicators in Education’s state performance report that are relevant to students receiving mental health services. Interviewed staff at each LEA to determine how the LEA tracks the outcomes for those students against the key performance indicators we identified. Assessed the practices and procedures for gaps that would cause the LEA to inadequately track the outcomes for these students. Interviewed staff at Education regarding its tracking of outcomes for students who received a mental health service through an IEP. |

| 10. To the extent possible, compare the number of students with diagnosed mental health issues in California to the number of students actually receiving services as part of an IEP. |

Searched for and reviewed available estimates of the number of school aged children in California with diagnosed mental health issues. Using data we obtained from Education, determined the total number of students in California whose IEP states that they will receive mental health services. |

| 11. Review and assess any other issues that are significant to providing mental health services to students. |

At the county mental health department that corresponds to the SELPAs selected in objective 4, we reviewed the available service records for the students that we selected for review under objective 5(c) for a three-year period. Interviewed staff at the county mental health departments to determine how to match county mental health services with the services listed on student IEP documents. Determined whether county mental health departments provided additional services to each of the selected students beyond what was included in the students’ IEPs. |

Sources: California State Auditor analysis of Joint Legislative Audit Committee audit request number 2015-112, and information and documentation identified in the table column titled Method.

Assessment of Data Reliability

In performing this audit, we obtained electronic data files extracted from the information systems at Education and Health Care Services. The U.S. Government Accountability Office, whose standards we are statutorily required to follow, requires us to assess the sufficiency and appropriateness of the computer processed information that we use to support our findings, conclusions, and recommendations. Specifically, we obtained student and service data from Education’s California Special Education Management Information System (CASEMIS) for the period from July 1, 2009, through June 30, 2015. For each school year, we used these data to identify students with an IEP and, for those students, whether their IEP included mental health services or residential treatment services, or indicated an emotional disturbance disability. Further, we used these data to compare the type, frequency, and providers of mental health services before and after the implementation of AB 114. To evaluate these data, we performed data set verification procedures and electronic testing of key data elements and did not identify any significant issues. However, we did not perform accuracy and completeness testing of the CASEMIS data because the source documents required for this testing are stored at various locations throughout the State, making such testing cost prohibitive. Thus, we determined that Education’s CASEMIS data were of undetermined reliability for the purposes of this audit. Although this determination may affect the precision of the numbers we present, there is sufficient evidence in total to support our audit findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

Additionally, we obtained Medi Cal eligibility data from Health Care Services’ Fiscal Intermediary Access to Medi Cal Eligibility system (beneficiary eligibility system) for the period from January 1, 2009, through June 30, 2015. We used these data to identify Medi Cal eligibility for students in the special education program. To evaluate these data, we performed data set verification procedures and found no errors. We also performed electronic testing of key data elements and found no issues in the fields used for this analysis. However, we did not perform accuracy and completeness testing of the beneficiary eligibility system data because the source documents required for this testing are stored at various locations throughout the State, making such testing cost prohibitive. Thus, we determined that Health Care Services’ beneficiary eligibility system data were of undetermined reliability for the purposes of this audit. Although this determination may affect the precision of the numbers we present, there is sufficient evidence in total to support our audit findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

Footnotes

4 The legislation that gave rise to this model of service provision was Assembly Bill 3632 (AB 3632) (Chapter 1747, Statutes of 1984), which was signed by the governor in September 1984. This mandate was suspended for fiscal year 2010–11, when the governor used a line-item veto to eliminate funding for the AB 3632 mandate.Go back to text

5 In fiscal years 2011–12 and 2012–13, according to the requirements of the state budget act, Education distributed some federal funds based on a different formula that incorporated information from Education’s California Special Education Management Information System..Go back to text

6 Individuals who are eligible for full-scope Medi-Cal services are eligible for the full range of Medi-Cal benefits, allowing for the most comprehensive Med-Cal coverage.Go back to text