Introduction

Background

The University of California (UC) and the California State University (CSU) are the two public university systems in California. UC was created by an 1868 statute as a public, state-supported, higher education institution, whereas the CSU system was established among individual existing colleges in 1982. UC has 10 campuses, and the CSU has 23 campuses throughout the State. The University of California Office of the President (UCOP) and the CSU Office of the Chancellor (Chancellor’s Office) oversee and support their respective systems.

The California State Constitution exempts state-owned property and property used exclusively for state colleges and universities, which include the UC and CSU campuses, from property taxation.2 Although individual campuses initiate property acquisitions, properties acquired by CSU campuses are owned by the CSU Board of Trustees, and properties acquired by UC campuses are owned by the UC Regents. However, for readability, throughout the report we refer to property acquisitions as properties having been acquired by an individual campus. When a CSU or a UC campus acquires taxable property or leases a property exclusively for educational purposes, generally that property no longer produces property tax revenue unless the campus subsequently leases or sells that property to a party whose property is not exempt from taxation. As a result of these tax exemptions, when universities expand their campuses by acquiring properties that formerly were taxable, the corresponding local governments may experience a decrease in revenue from property taxes.

Local governments, such as cities and counties, generally provide fire and emergency medical services to the campuses we reviewed. Funding for local fire departments comes primarily from the local governments’ general funds. The local governments’ general fund revenue can come from several sources, such as property taxes, sales taxes, hotel taxes, and the collection of fines related to parking and moving violations. For example, the city of San Diego’s fiscal year 2015–16 budget identified nearly $1.3 billion in general fund revenue, with approximately $470 million coming from property taxes. Because the properties that the UC and CSU campuses own are tax‑exempt, those properties generally do not contribute directly to the property tax revenue streams that fund their local governments’ fire and emergency services. Because property tax revenue is an important source of income for cities and counties, large reductions in the amount of property taxes each year could reduce the funds available for allocation to fire departments for fire and emergency medical services.

Counties Assess Property Taxes and Allocate Them to Local Governments

Campus Reviewed and the Corresponding Local Government Entity Providing Fire and

Emergency Services

California State University, Chico:

City of Chico

California State University, Dominguez Hills:

Los Angeles County

California State University, San Diego:

City of San Diego

California State University, San José:

City of San José

California State University, Stanislaus:

City of Turlock

University of California, Berkeley:

City of Berkeley

University of California, Merced:

Merced County

University of California, Santa Barbara:

Santa Barbara County

Sources: California State Auditor’s interviews with campus staff and review of relevant documents.

Real property in California is generally subject to property taxation, although state law exempts some types of property, such as property owned by the State or property used exclusively for religious worship. State law requires each county to impose a property tax rate of 1 percent. Property is taxed on its taxable value, which is determined according to provisions of Proposition 13, which voters approved in 1978, and subsequent state law. For example, if in a given fiscal year the tax rate is 1 percent and the value of a piece of property acquired in that fiscal year is $100, the property tax on that property would generally be $1 for that fiscal year. Except for certain property that the State Board of Equalization assesses, each county’s assessor is responsible for establishing the taxable value of all property subject to property tax in that county, and that value can vary over time and is subject to limits established in state law. The county assessor calculates property value by increasing the initial assessed value at the time of purchase by 2 percent or the annual inflation rate, whichever is less. The taxable value is the lesser of this amount or the market value of the property. For example, if the market value of the property described above increased to $105 the next fiscal year, and if the inflation rate were 2.5 percent, state law would limit the taxable value increase to only 2 percent, resulting in a taxable value of $102.

Although state law requires each county to impose a 1 percent property tax rate, state law generally prohibits other local entities from imposing additional property taxes except in specified circumstances. One exception authorizes a county or other local entity in a county to impose an additional property tax so that the entity can make annual payments for certain voter‑approved debt. For example, in Los Angeles County, properties are subject to taxation by a number of taxing agencies, such as cities, school districts, and special districts. As a result, the property tax rate can be a little more than the 1 percent specified in state law. For instance, the property tax rate for some tax rate areas in Los Angeles County was 1.12 percent for fiscal year 2014–15.

Each county collects all property taxes imposed in its jurisdiction and apportions the revenue collected to the different local entities within the county. State law generally requires that each local entity be apportioned property tax revenue equal to what it received in the prior fiscal year plus its proportional share of any change in this revenue. For example, a city receives only a portion of all the property taxes collected on properties within its boundaries because the county, school districts, and any relevant special districts also each receive a portion of that property tax revenue.

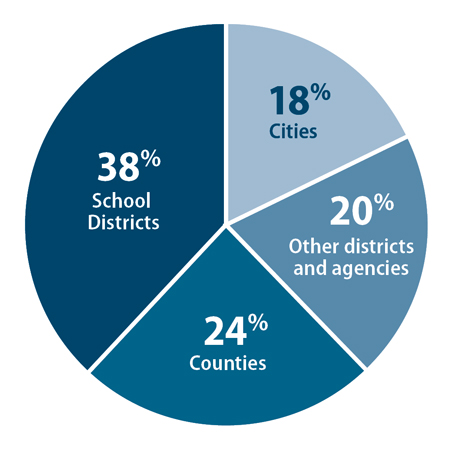

Because the property taxes that a county collects on properties located within a city are apportioned to multiple local entities, growth or reduction in these property taxes helps or hurts multiple local governments and districts but in varying dollar amounts. Figure 1 shows the proportion of property taxes each type of local government received in fiscal year 2014–15 as a result of this county-by-county process.

Figure 1

Proportion of Statewide Property Taxes That Each Type of Local Government Received

Source: Legislative Analyst’s Office article titled “Local Governments’ Services & Their Property Tax Revenue”, December 16, 2015.

Note: A city, a county, or a special fire district may provide fire and emergency medical services depending on the location of the entity receiving the services.

Local Governments Provide Emergency Fire and Medical Services to the Campuses We Reviewed

Although the UC and CSU campuses do not pay property taxes, they generally receive certain services from their local governments. Specifically, each of the UC and CSU campuses we reviewed receives fire and emergency medical services from either the city or the county where they are located. For example, according to the associate vice president of real estate, planning and development at CSU San Diego, the city of San Diego provides fire and emergency services to the campus. On the other hand, UC Santa Barbara, which is located in an unincorporated area, receives fire and emergency medical services from Santa Barbara County. The text box on page 6 names the local government that provides fire and emergency medical services to the campuses we reviewed.

Scope and Methodology

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee (audit committee) directed the California State Auditor to perform an audit of selected UC and CSU campuses to identify property tax revenue losses to local governments because of expansions by the CSU and UC campuses. The audit committee also asked us to identify any related increases in funding for local fire departments that provide safety services to campuses and their surrounding communities to offset such tax revenue losses. Table 1 lists the audit’s objectives and the methods we used to address them.

| Audit Objective | Method | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Review and evaluate the laws, rules, and regulations significant to the audit objectives. | Reviewed the relevant laws, regulations, and other background materials applicable to property taxes and the provision of fire and emergency medical services to California State University (CSU) and University of California (UC) campuses. |

| 2. | Determine the CSU and UC policies, procedures, and practices for engaging with the local community or other regional association of governments before approving any property acquisition, construction, or expansion project for campus use. |

Using campus accounting records, identified all acquisition and construction projects completed between January 1, 2010, and June 30, 2015, and performed the following at each campus:

|

| 3. | For the past five fiscal years, determine the budgetary allocations made by the CSU and UC systems to a selection of four CSU and three UC campuses for the provision of fire protection and emergency medical services to the campuses and their surrounding communities. |

|

| To the extent possible, identify all properties that have been acquired or constructed by a selection of four CSU and three UC campuses since January 1, 2010. Using this information, determine the following: | Because the four selected CSU campuses had very few, if any, acquisitions, we reviewed acquisitions at one additional campus—CSU Chico—that the Chancellor’s Office identified as having multiple property acquisitions since January 1, 2010. For these five CSU campuses and the three UC campuses, we performed the following:

|

|

| a. The current assessed value of all the property. |

|

|

| b. In cases where the CSU or UC campus has acquired property that was previously private, the estimated loss of property tax revenue associated with the property. |

For each previously taxable property acquired between January 1, 2010, through June 30, 2015, we obtained the following property tax information from the relevant county assessor’s, tax collector’s, or auditor controller’s office:

Using the information obtained, we calculated the estimated property tax loss to the local government where the acquiring campus is located using both the assessed value of the property and the property’s acquisition price. Compared the estimated property tax revenue loss since the time of acquisition to the total property revenue for the relevant local government over the same period. To estimate the property tax impacts of exemptions granted to campuses that leased otherwise taxable property, we did the following:

Using information obtained from the relevant county tax collector’s or auditor-controller’s offices, calculated the estimated total countywide property tax impact of each campus’s lease exemptions in fiscal year 2014–15. To estimate the property tax impacts of campus-owned properties that are leased to private third parties and are therefore taxable we obtained the following property tax information from the relevant county assessor’s, tax collector’s, or auditor controller’s office:

|

|

| 5. | Determine whether any CSU or UC campus has an existing contract, agreement, or any other in lieu payment arrangement with its neighboring fire agency to offset the revenue loss to that agency due to campus property acquisitions, construction, or expansions. |

|

| 6. | For a selection of four CSU and three UC campuses, determine whether the local government that hosts the campus or its property has placed a local tax measure on the ballot since January 1, 2010, to pay for public safety services. |

For each of the seven originally selected campuses, performed the following:

|

| 7. | Review and assess any other issues that are significant to the audit. For the seven originally selected campuses, performed the following: |

|

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of Joint Legislative Audit Committee audit request number 2015-106 and information and documentation identified in the table column titled Method.

Methods to Address Data Reliability

In performing this audit, we obtained electronic data files extracted from the information systems listed in Table 2. The U.S. Government Accountability Office, whose standards we are statutorily required to follow, requires us to assess the sufficiency and appropriateness of computer-processed information that we use to support our findings, conclusions, or recommendations. Table 2 describes the analyses we conducted using data from these information systems, our methodology for testing them, and the conclusions we reached as to the reliability of the data. Although these determinations may affect the precision of the numbers we present, we found sufficient evidence in total to support our audit findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

| Information System | Purpose | Method and Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Four California State University (CSU) Campuses—CSU Dominguez Hills, CSU Stanislaus, CSU Chico, and CSU San José PeopleSoft CSU campuses’ accounting data for fiscal years 2009–10 through 2014–15 |

|

|

Complete for the purpose of this audit. |

|

California State University, San Diego (San Diego State) Oracle San Diego State’s accounting data for fiscal years 2009–10 through 2014–15 |

|||

|

University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley) PeopleSoft UC Berkeley’s accounting data for fiscal years 2009–10 through 2014–15 |

|||

|

University of California, Merced (UC Merced) University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Financial System UC Merced’s accounting data for fiscal years 2009–10 through 2014–15 as maintained by UCLA's financial system |

|||

|

University of California, Santa Barbara (UC Santa Barbara) UC Santa Barbara Mainframe Com‑Plete Services UC Santa Barbara’s accounting data for fiscal years 2009–10 through 2014–15 |

|||

|

County Assessors, Collectors, and Auditor‑Controllers Property tax assessment, billing, and allocation systems Property tax assessments and collections for fiscal years 2009–10 through 2014–15 |

|

We did not perform accuracy and completeness testing on these data because testing the number and variety of data systems used in this audit would be cost-prohibitive. | Undetermined reliability for the purposes of this audit. Although these determinations may affect the precision of the numbers we present, there is sufficient evidence in total to support our audit findings and conclusions. |

|

UC Berkeley Tri-Tech Records Management System Fire and emergency medical incidents involving the local fire department for fiscal years 2009–10 through 2014–15 |

To identify any trend in the number of fire and emergency medical incidents at UC Berkeley involving the local fire department. | We did not perform accuracy and completeness testing on these data because testing the number and variety of data systems used in this audit would be cost-prohibitive. | Undetermined reliability for the purposes of this audit. Although these determinations may affect the precision of the numbers we present, there is sufficient evidence in total to support our audit findings and conclusions. |

|

County of Merced Fire Department Computer Aided Dispatch System Fire and emergency medical incidents involving the local fire department for fiscal years 2009–10 through 2014–15 |

To identify any trend in the number of fire and emergency medical incidents at UC Merced involving the local fire department. | We did not perform accuracy and completeness testing on these data because testing the number and variety of data systems used in this audit would be cost-prohibitive. | Undetermined reliability for the purposes of this audit. Although these determinations may affect the precision of the numbers we present, there is sufficient evidence in total to support our audit findings and conclusions. |

Sources: California State Auditor's analysis of data obtained from selected California State University and University of California campuses, and the offices of county assessors, county collectors, and county auditor-controllers.

Footnotes

2 According to UC’s tax manager, when UC purchases property for investment purposes, generally through a limited liability corporation, it is not exempt from property taxation in California. Go back to text