Introduction

Background

To help mitigate the overpumping of groundwater in southeastern Los Angeles County, the public voted to establish the Central Basin Municipal Water District (district) in 1952 under the Municipal Water District Law of 1911. The district’s founders realized they would have to curtail the region’s use of relatively inexpensive yet diminishing local groundwater by providing it with imported water. The district’s stated mission is to exercise the powers given to the district under its establishing act, utilizing them to the benefit of parties within the district and beyond. The district’s mission includes acquiring, selling, and conserving imported water and other water that meets all required standards and furnishing it to customers in a planned, timely, and cost‑effective manner that anticipates future needs.

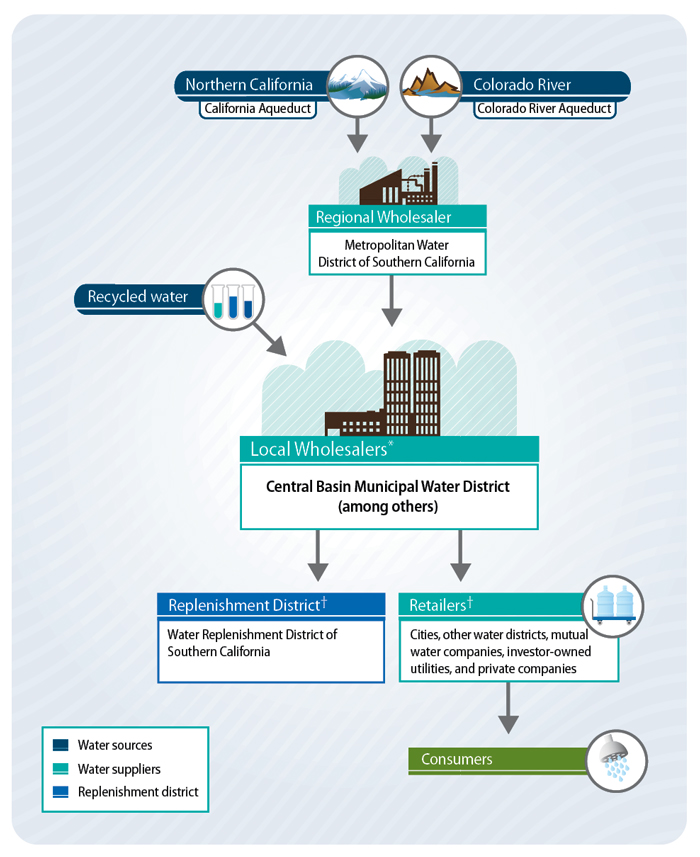

In 1954, the district became a member agency of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (Metropolitan), an agency that provides the Southern California region with water that it imports from Northern California and from the Colorado River. The district purchases the imported water from Metropolitan and wholesales it to cities, mutual water companies, investor‑owned utilities, and private companies. Further, the district supplies water for groundwater replenishment and provides the region with recycled water for municipal, commercial, and industrial use. Figure 1 provides an overview of the system of water supply and delivery in Southern California.

Figure 1

Central Basin Municipal Water District’s Role in Water Delivery

Sources: Documents obtained from the websites of the named entities.

* Members of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (Metropolitan).

† Nonmembers of Metropolitan.

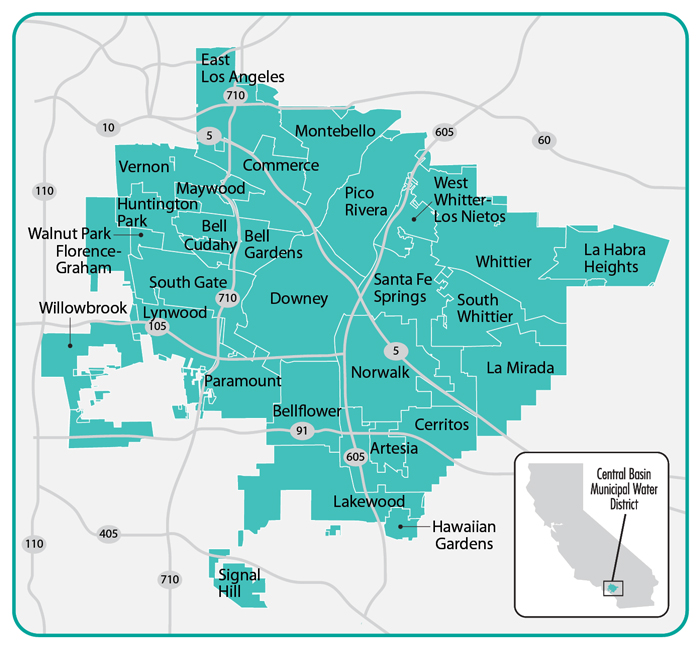

The district currently serves a population of more than two million people in 24 cities in southeast Los Angeles County and in some unincorporated areas of the county. Its mission statement indicates that it provides leadership, support, advice, and information on water issues to the people and agencies within and outside its boundaries, as appropriate. For example, the district supplies information on drought‑conservation measures to the public and provides water education courses and materials to students. According to its comprehensive annual financial report, the district’s 227‑square‑mile service area used approximately 241,000 acre‑feet of water in fiscal year 2013–14.1 Figure 2 shows the district’s boundaries and the cities included within those boundaries.

Figure 2

Central Basin Municipal Water District’s Service Area

Source: Central Basin Municipal Water District’s website.

The District’s Governance and Administration

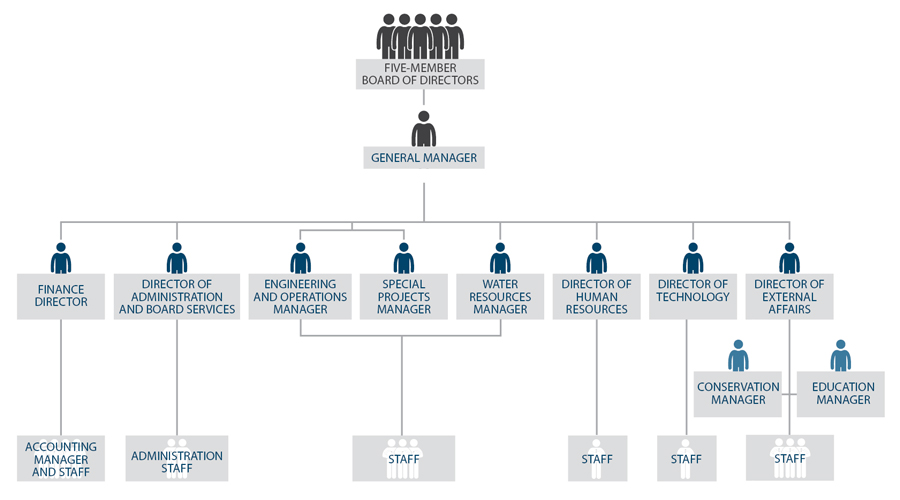

A five‑member board of directors (board) governs the district. Each board member represents one of five divisions within the district and is elected to a four‑year term by the voters within that division. No limits exist on the number of terms a board member may serve; according to the district’s website, the longest‑serving member of the board was in his fifth four‑year term as of September 2015. Board elections are nonpartisan and held during November general elections.2 According to state law, the board is ultimately responsible for the performance of the district’s powers, privileges, and duties. Toward this end, the district’s administrative code states that the board’s responsibilities include ensuring that the district is managed well, determining its objectives and policies, approving its annual budget, and appointing its general manager. As we discuss further in Chapter 3, board members receive compensation for their service in the form of a payment for each day they attend meetings and other events on district business. They also receive medical and other health benefits equivalent to those of full‑time employees of the district.

The general manager is the chief executive of the district and is responsible to the board for the district’s administrative affairs. The general manager prepares and recommends the district’s annual budget, hires its employees, and manages its day‑to‑day operations, among other duties. As of July 2015 the district had a total of 23 authorized positions, including the general manager. Figure 3 presents the organization of the district.

Figure 3

Central Basin Municipal Water District Organizational Chart

Source: Central Basin Municipal Water District’s website.

For more than 15 years the district shared administration with a companion organization, the West Basin Municipal Water District (West Basin). West Basin performs similar functions to the district but for communities in southwest Los Angeles County. Between 1990 and 2006 the two districts shared staff and an office building. However, in 2006 West Basin took action to end the partnership. West Basin purchased the office building, and the district relocated its headquarters to the City of Commerce, California.

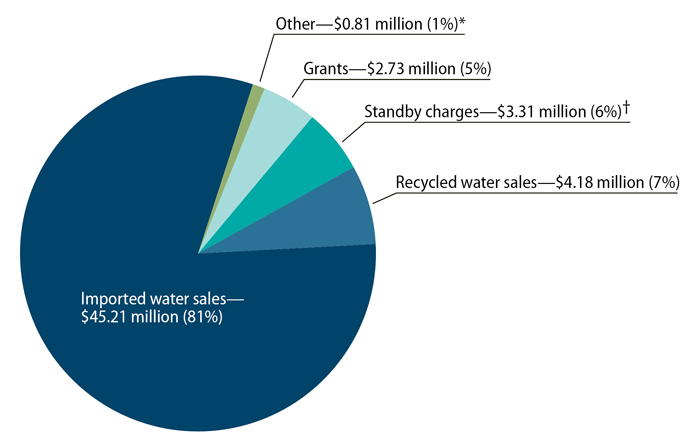

District Revenue

The district’s primary source of operating revenue is the sale of imported water and, to a lesser degree, recycled water. Figure 4 shows the distribution of district revenue by source during fiscal year 2014–15. Its revenue from the sale of imported water was about $45 million, or 81 percent of its total revenues, in fiscal year 2014–15, while its sales of recycled water accounted for about $4 million, or 7 percent of its total revenues, in the same period.

Figure 4

Central Basin Municipal Water District’s Revenue Sources by Major Category

For Fiscal Year 2014–15

Source: Central Basin Municipal Water District’s (district) fiscal year 2014–15 draft financial statements as of October 2015.

* The district derives other revenues from deliveries of treated water, investment income, and other miscellaneous sources.

† Standby charges are imposed by the district on landowners and used by the district to help pay its debt service costs on its water recycling facilities and the purchase of its headquarters building.

The district’s other significant source of revenue is standby charges that the district imposes on landowners with the annual approval of its board. Los Angeles County includes the charge on each property owner’s property tax bill. The standby charge’s purpose is to minimize the effects of the drought on the area through the construction of recycled water distribution systems that could provide an alternative source of water. The district currently uses revenue from the standby charges to pay debt service on the debt it issued to finance the construction of its water recycling facilities, as well as to pay for the acquisition of its headquarters building. The district’s standby charges accounted for about $3 million, or 6 percent of its total revenues, in fiscal year 2014–15.

Recent Scrutiny of the District

The district and its board have come under scrutiny in recent years. News reports have alleged that the district misused public funds, including that it established a legal trust fund in a manner that violated state open meeting law, that it inappropriately reimbursed meal expenses, and that it engaged in inappropriate contracting practices and employment practices. We address these allegations in this report. In addition, the district has been involved in a number of lawsuits over the past several years. Although many of these lawsuits have been settled or dismissed, a small number related to the district’s employment practices are still pending.

In October 2014 the County of Los Angeles Department of Public Works published a report on the district that sought to ensure it addressed its ongoing problems so that it could continue to provide water and service to its customers. The report recommended an independent management audit of the district’s operations and included a discussion of the process necessary to dissolve the district and transfer its functions to another entity. We discuss this report further in Chapter 1.

Scope and Methodology

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee (audit committee) directed the California State Auditor’s office to perform an audit of various aspects of the district’s operations, including its contracting, expenditures, strategic planning, financial viability, and human resources. Table 1 includes the audit objectives the audit committee approved and the methods we used to address them.

| Audit Objective | Method | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Review and evaluate the laws, rules, and regulations significant to the audit objectives. | We reviewed relevant state laws and regulations. |

| 2 | Assess whether the Central Basin Municipal Water District (district) has appropriate policies, processes, and oversight for various aspects of its operations. Specifically, perform the following covering the five‑year period from 2010 to 2015: a. Assess whether the district’s board of directors (board) has sufficient policies and practices to guide its spending decisions. In addition, determine whether the board exercises sufficient oversight regarding expenditures. |

For our audit period of July 1, 2010, through June 30, 2015:

|

| b. Assess whether the district has sufficient processes and controls to ensure expenditures and other financial activities are appropriate. |

|

|

| c. Review the district’s contracting procedures and determine whether they are consistent with applicable contracting requirements and with procedures used by other municipal water districts. From a selection of contracts, determine whether the district complied with the applicable laws, policies, and regulations. |

|

|

| d. Assess whether the district has adequate resources and policies to address personnel matters, including the conduct of its board members. |

|

|

| e. Assess whether the district operates transparently, including complying with laws governing public meetings, public records, and fee‑setting, and whether it publicly reports on all its spending. |

|

|

| 3 | Assess whether the district’s expenditures and revenues are reasonable. Specifically, perform the following covering the five‑year period from 2010 to 2015: a. To the extent possible, assess the reasons for any trends in revenues generated through customer rates during the past five years. |

|

| b. For major categories of expenditures, assess the reasons for any major trends, including those expenditure trends related to legal matters and those not directly related to the district’s primary mission. |

|

|

| c. For a sample of expenditures, determine whether they were legally allowable, reasonable, and consistent with the mission of the agency. |

|

|

| 4 | To the extent the district has a strategic plan, determine the following: a. Whether the strategic plan contains goals and objectives that support the mission of the organization. b. How often the district evaluates its success in achieving its goals and objectives, and updates the strategic plan to reflect changes, including changes in regulatory requirements, goals, and milestones. |

|

| 5 | Assess whether the district has qualified staff to manage its operations. Specifically, perform the following: a. To the extent possible, determine whether technical staff has sufficient qualifications and resources to adequately maintain its infrastructure over the long term. |

|

| b. To the extent possible, assess the qualifications and sufficiency of the district’s management staff responsible for essential operations. |

|

|

| c. Identify the total compensation of each member of the board of directors and top managers. |

|

|

| d. Determine whether the total compensation received by each of the district’s top managers is comparable to that received by top managers in similar public agencies or municipal water districts in the region. |

|

|

| 6 | Assess the district’s financial viability and control environment. Specifically, for the five‑year period from 2010 to 2015, determine the following: a. Whether the district retained a qualified, independent auditor for its annual financial audits and whether completed audits were publicly available. |

|

| b. What deficiencies were reported by its independent auditor and how the district has addressed such deficiencies. |

|

|

| c. How often the district changed auditors and the reasons for changing auditors. |

|

|

| d. The district’s debt ratio coverage for bond commitments and the reasons for any year in which the ratio fell below the generally accepted level. |

|

|

| e. To the extent possible, assess whether the five‑year trends in revenues and expenditures indicate long‑term financial viability. |

|

|

| 7 | Review and assess any other issues that are significant to the district’s operations and management. |

|

Sources: The California State Auditor’s analysis of Joint Legislative Audit Committee audit request 2015‑102 and information and documentation identified in the table column titled Method.

Assessment of Data Reliability

In performing this audit, we relied upon reports generated from the information systems listed in Table 2. The U.S. Government Accountability Office, whose standards we are statutorily required to follow, requires us to assess the sufficiency and appropriateness of computer‑processed information that is used to support our findings, conclusions, or recommendations. Table 2 shows the results of this analysis.

| Information System | Purpose | Method and Result | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Basin Municipal Water District’s (district): – New Logos Database data, for the period July 2012 through June 2015 – Master Accounting Series 90 data, for the period July 2010 through June 2012 |

To make a judgmental selection of expenditures |

• This purpose did not require a data reliability assessment. Instead, we needed to gain assurance that the population of expenditures was complete for our review purposes. • We obtained reasonable assurance by comparing total disbursements presented on the expenditure lists to the district’s monthly bank reconciliations or payment register reports. |

As part of our audit work, we identified certain transactions not present on the district’s expenditure lists. Nevertheless, we noted that these lists materially agreed with monthly bank reconciliations or payment register reports, and were thus adequate to use for selecting expenditures for review. |

| To calculate per diem payments the district made to its board members | To determine accuracy, we judgmentally selected 50 board‑approved per diem payments from the district’s records and compared them to claim forms detailing the meetings board members attended. To determine completeness, we reviewed district records and noted directors generally received per diem payments in each pay period between July 2010 and June 2015. | Sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this audit. | |

|

The district’s: – New Logos Database data, for the period July 2012 through June 2015 – Access Database data, for the period July 2010 through June 2012 |

To make a judgmental selection of contracts | This purpose did not require a data reliability assessment. Instead, we needed to gain assurance that the population of contracts was complete for our review purposes. To determine completeness, we haphazardly selected 39 contracts from the district’s files and ensured they were present in either the New Logos or Access database, as appropriate. | Complete for the purposes of this audit. |

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of various documents, interviews, and data obtained from the district.

Footnotes

1 An acre‑foot of water is approximately 326,000 gallons, which the district states is enough to meet the water needs of two average families in and around their homes for one year. Go back to text

2 In 2012 the district received approval from Los Angeles County to change its election to June for that year only. Go back to text