Chapter 2

The State Bar of California Dedicated a Significant Portion of Its Funds to Purchasing a Building in Los Angeles and Did Not Fully Disclose Critical Financial Information

Chapter Summary

The State Bar of California’s (State Bar) primary mission is the protection of the public through its attorney discipline system. However, the State Bar’s financial priorities over the past six years did not consistently reflect that mission: Rather than using its financial resources to improve its attorney discipline system, the State Bar dedicated a significant portion of its funds to purchase and renovate a building in Los Angeles in 2012. Although the Legislature approved $10.3 million for this building, the State Bar ultimately spent approximately $76.6 million on it. Facilitating this purchase required the State Bar to transfer $12 million between its various funds, some of which its Board of Trustees (board) had set aside for other purposes. For example, the State Bar paid for renovations, including information technology (IT) upgrades, to the Los Angeles building in part by using funds its board had designated for new IT systems, even though the State Bar’s strategic plan identified the new systems as a high priority.

The ultimate responsibility for ensuring that the State Bar spends funds prudently rests with the board, which should have ensured that the State Bar’s decision to purchase the Los Angeles building was justified and financially beneficial. However, the State Bar did not fully communicate its questionable financial decisions regarding this new building to the board because it never presented its board with comprehensive cost estimates of purchasing versus leasing a building. Moreover, only four months before it purchased the Los Angeles building, the State Bar informed the Legislature in an annual report that a building would cost $26 million—a third of the $76.6 million the State Bar ultimately paid. In addition, the State Bar could offer no evidence that it informed the Legislature of its final decision to purchase the Los Angeles building even though state law required it to do so. As a result, key decision makers and stakeholders lacked the information necessary to make informed financial decisions related to the purchase of the Los Angeles building or to understand its impact on the State Bar’s other financial priorities.

The State Bar’s fund balances over the last six years indicate that the revenues from annual membership fees exceeded the State Bar’s operational costs, which gave the State Bar the flexibility to purchase the Los Angeles building. Although the purchase of the building decreased the State Bar’s available fund balances, we found that these balances are again beginning to increase, calling into question whether the revenues the State Bar collects are reasonable. However, the State Bar has not conducted certain long‑term planning—such as a thorough analysis of its revenues, operating costs, and future operational needs—that would justify the revenues it collects. Because the Legislature must authorize the State Bar to collect membership fees, which fund a significant portion of its operations, on an annual basis, long‑term planning is difficult. Thus, a funding cycle that gives the State Bar a greater certainty of funding—for example, a biennial funding cycle—could enhance its ability to engage in long‑term planning.

The State Bar Made Questionable Financial Decisions When Purchasing Its Los Angeles Building

State law requires that public protection be the State Bar’s highest priority, and we believe that includes the responsibility to spend revenues in such a way so as to protect the public from attorneys’ unlawful or inappropriate acts. However, the State Bar has not sufficiently met its responsibilities. In particular, rather than using its available fund balances to improve its attorney discipline system—such as ensuring that the staffing levels for its discipline‑related functions are adequate—the State Bar spent $76.6 million to purchase and renovate a building in Los Angeles. Moreover, the State Bar purchased this building without a thorough cost‑benefit analysis and used some funds designated for new IT projects and other board‑restricted funds.

The State Bar Used Fund Balances and Resources Set Aside for Other Purposes to Purchase and Renovate a Building in Los Angeles

In 2012 using various sources of funds, including fund balances that had been growing over time, the State Bar purchased and renovated a new building located in downtown Los Angeles, as shown in Figure 10, spending a total of approximately $76.6 million. In anticipation of the State Bar’s Los Angeles lease expiring in January 2014, the Legislature had approved a temporary five‑year $10 special assessment charged to members between 2009 and 2013 as a means to pay for the financing, leasing, construction, or purchase of a building in Southern California. According to the acting executive director, the last time the Legislature authorized the State Bar to collect a $10 building special assessment was in 1986, and at that time the purpose of the assessment was to cover the cost of the State Bar’s properties. When the State Bar again sought a special assessment in 2008, it did not provide the Legislature with any analyses of the estimated cost to purchase a new building in Southern California. Ultimately, the special assessment collected between 2009 and 2013 generated only $10.3 million—about $66 million short of the final cost of the Los Angeles building.

Figure 10

Map of Los Angeles Building

Source: Google Maps, 845 South Figueroa Street, Los Angeles, CA 90017.

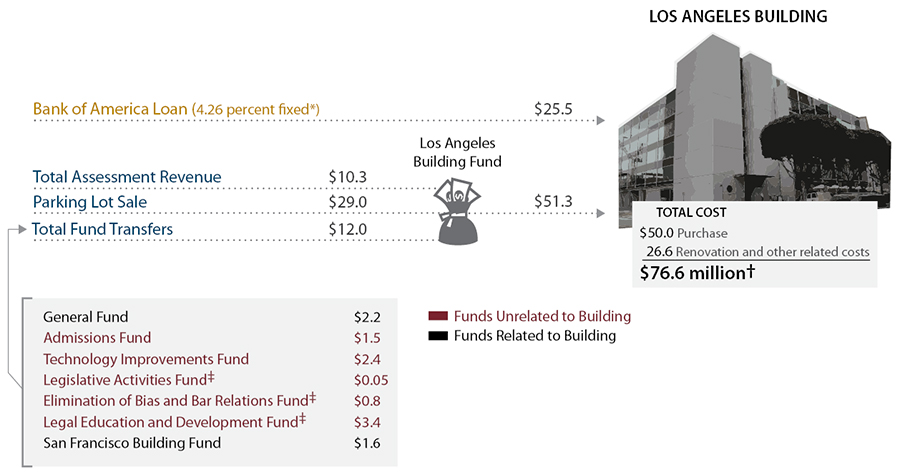

To finance the remaining cost of the Los Angeles building, the State Bar secured a $25.5 million loan, sold a parking lot in Los Angeles for $29 million, and engaged in a series of fund transfers amounting to $12 million, as shown in Figure 11 below. Two of the transfers—$1.6 million from the San Francisco Building Fund and $2.2 million from the State Bar’s general fund—were reasonable uses of funds to help purchase the Los Angeles building, given the purposes of those two funds. However, our analysis found that approximately $8.2 million of the $12 million that the State Bar transferred from other funds to pay for its new building came from funds whose purposes bore little relation to the Los Angeles building. For example, in 2013 the State Bar transferred $4.3 million from the Administration of Justice Fund, which includes funds to pay for programs that seek to eliminate bias in the judicial system and legal profession and increase participation by attorneys who are underrepresented in the State Bar’s administration and governance, fund legal education and development services, and also fund legislative activities. In another example, in 2012 the State Bar transferred $1.5 million to the Los Angeles Facilities Fund from the Admissions Fund, which receives fees from individuals taking the State Bar examination and which the State Bar uses to pay for expenses related to developing and administering the examination. Finally, the State Bar made three transfers totaling $3.1 million in 2012 to fund its IT plan, and subsequently in 2013 transferred $2.4 million from its Technology Improvements Fund to its Los Angeles Facilities Fund. Without receiving these three transfers, the Technology Improvements Fund would not have had enough funding to make the transfer to the Los Angeles Facilities Fund.

Figure 11

Financial Resources the State Bar of California Used to Purchase Its Los Angeles Building

(In Millions)

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of data from the State Bar of California’s (State Bar) accounting system and the State Bar’s audited financial statements for 2012 and 2013.

* The State Bar must maintain $4.6 million as a debt service reserve fund per the loan agreement, which it maintains in its Public Protection Fund.

† According to the State Bar, the total cost of the building as of December 2014 was $74.6 million. However, it was unable to reconcile the difference between that amount and the $76.6 million we cited above. Therefore, we used the amount reported in the audited financial statements.

‡ The Administration of Justice Fund includes the Legislative Activities Fund, Elimination of Bias and Bar Relations Fund, and Legal Education and Development Fund.

In a January 2015 report to the board, the State Bar acknowledged that it made excessive fund transfers totaling $5.8 million for the purpose of purchasing the Los Angeles building, including transferring board‑restricted funds. It specifically cited its $1.5 million transfer from the Admissions Fund and a $4.3 million transfer from the Administration of Justice Fund, which it considered to be a loan. The acting executive director stated that the $1.5 million transfer from the Admissions Fund was justified because a large portion of admission staff works in the Los Angeles building. However, the acting executive director could not explain how the State Bar determined that the $1.5 million was a reasonable amount to transfer, nor could he provide analysis to support the other transfers. He indicated that the former chief financial officer—who no longer works at the State Bar—was more knowledgeable about the fund transfers. Subsequently, after we began inquiring about these transfers, the State Bar repaid the $4.3 million to the Administration of Justice Fund in April 2015, which it made effective as of December 2014. The acting general counsel explained that the State Bar repaid the funds to avoid the interest costs for the remaining term of the loan.

Irrespective of the State Bar’s explanations for the fund transfers, it does not have a policy to prevent it from transferring revenues to unrelated funds or using them for unrelated purposes. As described in the Introduction, except for the general fund, each of the State Bar’s funds either has a specific board‑defined purpose or acts as a repository for revenues collected for a specific statutory purpose. We believe sound policies and procedures to use transferred revenues only for their originally intended purpose would prevent the questionable uses of funds. The State Bar plans to develop these policies and procedures by July 2015.

The State Bar also made a troubling financial decision related to the Los Angeles building purchase when it used $4.6 million from its Public Protection Fund as collateral for the $25.5 million loan it used to buy the building. The State Bar created the Public Protection Fund to assure continuity of its attorney discipline system and other essential public protection programs in the event that state law should ever cease to authorize it to collect membership fees. Currently, the State Bar’s 15‑year loan agreement requires it to maintain a $4.6 million deposit as a debt service reserve—which the State Bar maintains in the Public Protection Fund—until it repays the loan. Because this fund had a $6.5 million fund balance as of December 2014, only $1.9 million would have been available at that time to support the operation of the discipline system should the State Bar have been unable to assess fees for a year. Further, according to the acting general counsel, if the State Bar were to default on the $25.5 million loan for the Los Angeles building, it would lose the $4.6 million in the Public Protection Fund—money that is critical to ensuring public protection related to the attorney discipline system in the event of a financial emergency.

The State Bar Did Not Sufficiently Justify Its Decision to Purchase the Los Angeles Building

The State Bar might have been able to justify the purchase of its Los Angeles building by performing a thorough cost‑benefit analysis to demonstrate that purchasing the building was more financially beneficial than continuing to lease space. However, it did not perform a cost‑benefit analysis before receiving board approval to purchase the building, and its April 2012 report to the Legislature on its preliminary plans for Southern California facilities underestimated the total cost of the purchase and renovation by more than $50 million.

Moreover, the State Bar did not adequately consider whether the purchased building would meet its long‑term staffing needs. In April 2012 the State Bar estimated that its Los Angeles operations could be housed in a 100,000‑ to 105,000‑square‑foot building, less than the 121,000 square feet it was occupying at the time. The building the State Bar ultimately purchased was 111,000 square feet. As we discussed in Chapter 1, the chief trial counsel told us that she would like to hire more staff in Los Angeles, but along with budget and recruiting difficulties, there is not adequate space in the new building to accommodate additional staff.

According to the acting executive director, the State Bar wanted to use the special building fee assessment to purchase a new building, if feasible. As previously discussed, this building assessment generated $10.3 million in revenue. The legislation adopting the $10 building assessment required that the State Bar rebate its members the full amount collected if it did not enter into an agreement to purchase a new building in Southern California by January 2014. We would have expected the State Bar to ask for an extension on this required rebate rather than purchasing a building that it did not have sufficient cash to purchase; however, the acting general counsel did not know whether the State Bar previously asked for an extension.

The State Bar’s decision to purchase the Los Angeles building also substantially limited its ability to provide a rebate to members to reduce its fund balances. Reducing the State Bar’s fund balances through member rebates has historical precedent: The Legislature required the State Bar to rebate each member $10 in 2012, for a total of approximately $2.2 million, because the State Bar’s general fund had a large surplus. After purchasing the Los Angeles building, the State Bar’s capital assets increased from $32 million to $102 million, or 219 percent. At the same time, its unrestricted fund balance for all funds decreased from $29.7 million to $8.5 million, or 71 percent, from 2011 through 2013. The unrestricted balance—prior to the decrease—may have otherwise been available to rebate to the State Bar’s members.

The State Bar Failed to Implement Its IT Strategic Plan

The fund transfers to the Los Angeles Facilities Fund may have also hindered the State Bar from implementing all elements of its IT strategic plan. The State Bar’s 2012–16 strategic plan (strategic plan) stated that the State Bar would retire and replace all four of its main software applications, including its Discipline Case Tracking System, by 2016. In total, the State Bar listed six IT projects in its strategic plan, which the text box describes, for an estimated cost of $9.6 million. Between 2011 and 2013 the State Bar used funds collected from a $10 fee assessment authorized by the Legislature to fund those IT projects and to upgrade IT infrastructure. The IT fee generated $5.2 million over those three years. In addition, in 2012 the State Bar transferred $1.2 million from its former Discipline Fund to pay for the Office of the Chief Trial Counsel’s case management system, $1 million from the Admissions Fund to pay for the admissions system, and $944,000 from the general fund to pay additional costs. In total, these sources provided the State Bar with $8.3 million—about $1.3 million less than the $9.6 million it needed to fully fund the IT strategic plan.

However, the State Bar did not use some of these funds for their designated purposes. Rather, it used $2.4 million in funds it originally designated for its new member system and IT contingencies to pay for a technology package of audio‑visual equipment, a security system, and an office acoustical system at the Los Angeles building. The documents that the State Bar provided to the board related to this transfer do not include any justification for changing the use of these funds. According to the acting executive director, the State Bar has delayed the new member system, in part, until it identifies another funding source. The senior director of the State Bar’s Office of Information Technology (senior IT director) stated that the State Bar has not completed the IT strategic plan for a variety of reasons, including changes in leadership and project management since 2012. Further, he stated that the State Bar encountered scope changes on the first project it started because the project was larger than estimated. The senior IT director noted that the Office of the Chief Trial Counsel’s case management system—one of the State Bar’s highest IT priorities—has suffered from a variety of delays because of scope, leadership, and project management changes. He believes that the State Bar will complete the Office of the Chief Trial Counsel’s case management system in 2016.

As a result of these decisions, the State Bar does not have enough remaining funds to complete the six IT projects it identified in its strategic plan. As shown in Table 9, as of December 2014 the State Bar had not completed any of the projects and had spent only a total of $1.52 million on them, even though it began collecting the IT fee over four years ago. The acting executive director stated that the State Bar is working on a funding plan to ensure that it completes the IT projects. As of December 2014 the State Bar had only $5.81 million available for IT projects, but needs at least $8.14 million to complete all six proposed IT projects.

| 2012–16 Strategic Plan Costs | Project Budget | Actual Expenditures as of December 2014 | Minimum Project Costs Remaining | Percentage of Budget Remaining | Percentage of Work Remaining* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Office of the Chief Trial Counsel’s Case Management System | $1.90 | $0.67 | $1.23 | 65% | 60% |

| State Bar Court’s Case Management System | 1.20 | 0.13 | 1.07 | 90 | 70 |

| Admissions System | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 | 100 | 95 |

| Member Records and Billing System | 1.90 | 0 | 1.90 | 100 | 100 |

| Systems Integration | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| Content and Document Management System | 0.90 | 0.36 | 0.54 | 60 | 40 |

| Online E‑Portal | 0.40 | 0 | 0.40 | 100 | 95 |

| Contingency† | 1.00 | 0 | 1.00 | 100 | NA |

| Totals | $8.14 | ||||

| REMAINING FUNDS AVAILABLE | The State Bar of California (State Bar) needs at least an additional $2.33 million to complete the projects in its information technology (IT) strategic plan. | ||||

| 2014 Technology Improvements Fund Balance | |||||

| 2014 Information Technology Special Assessment Fund Balance | |||||

| Total available funds | $5.81 | ||||

Sources: State Bar’s accounting system and its February 2012 State Bar Five‑Year Strategic Plan 2012–16.

NA = Not applicable.

* These percentages are estimates from the State Bar’s senior director of IT, as of April 2015.

† The Contingency budget is a reserve the State Bar included in the budget to accommodate variations in project costs.

The State Bar Did Not Adequately Communicate Its Financial Decisions to the Board or the Legislature

The ultimate responsibility for ensuring that the State Bar spends funds prudently rests with the board. We, therefore, would have expected the board to ensure that the State Bar’s decision to purchase the Los Angeles building was justified and financially beneficial. However, the State Bar did not adequately communicate its financial decisions to the board, limiting its ability to provide appropriate oversight. Further, the State Bar did not fully communicate its financial decisions to the Legislature, and as a result, decision makers lacked the information necessary to understand the impact of the purchase of the Los Angeles building.

The State Bar Did Not Give Its Board Adequate Information to Understand the Full Cost of the Los Angeles Building

The State Bar did not provide its board with enough information to understand the costs and benefits of purchasing or leasing a new building, to identify the full cost of the Los Angeles building, or to understand the fund transfers that the State Bar ultimately made to purchase the Los Angeles building. Although state law and board rules give the board the authority to make financial and property decisions related to the State Bar—including transferring funds among the State Bar’s various funds—the board cannot make informed, thoughtful decisions if it does not have adequate information.

According to the director of general services (services director) for the State Bar, who acted as the project manager of the Los Angeles building purchase and renovation, the State Bar presented the board only with options to buy a building rather than also including options to lease space. Our review of the State Bar’s communication with its board supports the services director’s statement. Specifically, the State Bar’s communication with its board about the Los Angeles building included the following:

- August 2012: The board’s operations committee authorized staff to proceed with an offer to purchase the Los Angeles building, not to exceed a $50 million purchase price and a total cost of $70 million to acquire, renovate, and improve the property for tenancy.

- September 2012: In a closed session the State Bar presented the board’s operations committee with cost comparisons for purchasing three different buildings in downtown Los Angeles. This presentation estimated that the State Bar would need no more than $15 million for tenant improvements. However, although the presentation asserted that leasing would cost about twice the annual operating costs of purchasing a new building, the State Bar did not include any actual cost estimates of future leasing options. Moreover, this cost comparison was not presented to the board until a month after it had authorized the State Bar to purchase the selected building in Los Angeles and had approved the building’s purchase price and budget for tenant improvements in August 2012.

- October 2012: According to the services director, the State Bar gave the full board a presentation similar to the one presented to the board’s operations committee and the board amended the State Bar’s budget to include the Los Angeles building purchase and estimated tenant improvements costs. However, this was a month after the State Bar completed the building purchase.

Thus, the information presented to the board did not support the notion that purchasing a building would be less expensive than leasing one. Further, the State Bar’s initial estimate that tenant improvements would cost no more than $15 million was incorrect. By 2015 this cost had increased to nearly $21 million due to refinement of the initial estimate and the State Bar’s decision to make technology upgrades to the Los Angeles building.

Moreover, the State Bar did not always provide the board with enough information to make informed decisions about the fund transfers it made to purchase the Los Angeles building. Although our analysis confirmed that the board approved the transfers to the Los Angeles Facilities Fund, on one occasion the State Bar did not fully inform the board about which funds it transferred. Specifically, in January 2013 the board approved a resolution allowing the State Bar to make transfers of up to $4.5 million to the Los Angeles Facilities Fund from a fund it called the “Administration of Justice Fund.” However, the State Bar instead transferred $4.3 million from three different funds: $782,000 from the Elimination of Bias and Bar Relations Fund, $3.5 million from the Legal Education and Development Fund, and $52,000 from the Legislative Activities Fund. According to the former budget director, the State Bar combines these three funds under the umbrella category of Administration of Justice Fund for budget purposes because the three funds are for substantially similar uses. However, the board policy manual that defines each of the State Bar’s funds does not indicate that the State Bar combined these funds into an Administration of Justice Fund. Based on the documentation the State Bar provided to the board, the board would not know which funds the State Bar used to purchase the Los Angeles building.

As described earlier, in January 2015 State Bar staff acknowledged that some of the transfers to the Los Angeles Facilities Fund involved board‑restricted funds and suggested that the board reverse the transfers. For example, the State Bar suggested that the board reverse a $1.5 million transfer from the Admissions Fund to the Los Angeles Facilities Fund that it approved in 2012. The board had previously restricted the spending of funds from the Admissions Fund to expenses related to administering the requirements for admission to the practice of law in California. According to the acting executive director, the staff’s suggestion to reverse the transfer caused the board members to question the State Bar’s lack of transparency when reporting to the board as opposed to the propriety of the fund transfer, and consequently the board had not taken any action to reverse the transfer as of April 2015. Both the acting executive director and the vice president of the board stated that the board can supersede the restrictions it places on funds. However, the meeting minutes do not provide evidence that the board openly discussed superseding a previous fund restriction when approving the transfer from the Admissions Fund.

Further, the board needs to have full and complete information to make informed financial decisions. According to the current board treasurer, the most recent annual budget proposal the State Bar submitted to the board in January 2015 was inadequate because it lacked cost‑center‑level detail. He explained that the board directed the State Bar to submit a more detailed budget, similar to what the State Bar submits to the Legislature, because the budget the board approves should be comparable to the budget the State Bar provides to the Legislature. In response to the board’s direction, in March 2015 the State Bar submitted to the board a more detailed budget with expenditures by cost center. Also in March 2015, the board’s executive committee released for public comment a draft rule adopting an open records requirement for the State Bar, including financial records. According to the board treasurer, this rule would allow public access to the State Bar’s financial records, which the public does not currently have.

The State Bar Did Not Fully Inform the Legislature of the Purchase of the Los Angeles Building

When it approved the $10 increase in State Bar fees in 2008 so that the State Bar could acquire a building in Southern California, the Legislature required the State Bar to submit annual reports over the five‑year period the fee increase was in place. Specifically, state law required the State Bar to report annually to the Legislature its preliminary plans for determining whether to construct, purchase, or lease a new office location in Southern California. However, the State Bar did not appropriately apprise the Legislature of its plan to purchase the Los Angeles building or that the purchase and other related costs had significantly increased. In its April 2012 report to the Legislature—four months before the board approved the purchase of the building—the State Bar estimated that the Los Angeles building would cost $26 million for the purchase and renovation of the building and relocation of staff. The report cited three potential funding sources for the building’s purchase: approximately $10.1 million in revenue collected from the $10 special building assessment included on its members’ annual fee statements, a $16 million long‑term loan, and an unstated amount from the sale of a parking lot the State Bar owned in Los Angeles. The 2012 report indicated that “it appears likely that the proceeds [of the parking lot sale] would enable the State Bar to extinguish most or all of the remaining loan balance and thus own its Los Angeles building outright.” After purchasing the Los Angeles building, the State Bar submitted two reports to the Legislature in February 2013 and 2014 that mentioned the building purchase; however, neither identified that the $26 million estimate it had earlier reported to the Legislature had soared to $76.6 million.

Most troubling is the fact that the State Bar could offer no evidence that it informed the Legislature of its decision to purchase the Los Angeles building, even though state law required it to do so. Specifically, in addition to requiring it to report annually on preliminary plans, state law required the State Bar’s board to submit its proposed decision and cost estimate to the Legislature’s Assembly and Senate judiciary committees at least 60 days before entering into any agreement for the purchase of a building in Southern California. The acting general counsel confirmed that the State Bar did not submit the required written report, asserting that it instead reported the proposed purchase verbally to several legislative staff. The acting general counsel also explained that the State Bar provided the legislative staff with a printed presentation showing the Los Angeles building the State Bar had chosen and other cost options, but he was unable to locate a copy of this handout.

Moreover, the State Bar did not accurately or fully communicate the status of the IT strategic plan to the Legislature. State law required that the State Bar report to the Legislature on the use of its $10 IT special assessment fee by April 1 of each year. However, the April 2013 report did not accurately reflect the actual status of the State Bar’s IT projects. For example, the State Bar reported to the Legislature that it had not started the member records and billing system (member system) replacement project but planned to complete it by 2015. However, three months later, the State Bar requested that the board approve a $2.4 million fund transfer from the Technology Improvements Fund by redirecting funds that it had “earmarked for the replacement of the [member system] in 2015” and IT contingencies to pay for technology improvements for the new Los Angeles building. According to board documents, making this transfer “could delay the replacement of that system if the [State Bar] is unable to identify other resources for the project.”

In addition to the reports related to the $10 IT assessment fee, state law required the State Bar to report annually on the status of its strategic plan implementation. However, in its 2014 report to the Legislature on the strategic plan’s status, the State Bar did not communicate that it had redirected $2.4 million in funding designated to develop the member system and IT contingencies to pay for technology improvements for the new Los Angeles building, as discussed previously. Instead, the 2014 report stated that the State Bar still intended to fully implement the new member system. According to the senior IT director, the State Bar has not yet sought new funding sources for the member system because it does not plan to begin its development until after completion of three other IT systems: the Office of the Chief Trial Counsel’s case management system, the State Bar Court’s case management system, and the admissions system. As a result, it is unclear when it will replace the existing member system. Moreover, the State Bar’s 2013 and 2014 reports did not include how much funding the State Bar had available and how much it had spent to date on each IT project.

The State Bar’s Fund Balances Indicate that Revenue From Annual Membership Fees Exceeded the State Bar’s Operational Costs

The State Bar’s fund balances over the last six years indicate that the revenues from annual membership fees exceeded the State Bar’s operational costs. As we discussed earlier in this chapter, using the accumulated fund balances and other sources, the State Bar purchased a $76.6 million building in Los Angeles, even though the State Bar did not sufficiently justify the purchase. Although that decision decreased the State Bar’s unrestricted fund balance from $29.8 million in 2011 to $8.6 million in 2013, it is again beginning to increase: the unrestricted balance grew from $8.6 million in 2013 to $20.2 million in 2014. As shown in Table 3 in the introduction, the State Bar maintained a combined fund balance of approximately $138 million in 2014, representing its 26 funds—the equivalent of about one year of its operating expenditures.

This trend suggests a continuous incongruence between the State Bar’s revenues and expenditures. A potential explanation is that the level of the State Bar’s membership fee has not taken into account the growth in the number of State Bar members. Specifically, the State Bar’s total expenditures have decreased by 4 percent over the past six years, while its membership fee revenues have increased steadily by about 12 percent. Even though the membership fee increased only slightly for active members, rising from $410 to $420 over the same time period, the outpacing of fee revenues collected compared to expenditures is more likely the result of a 10 percent increase in the number of paying State Bar members—from 205,000 members in 2009 to 226,000 in 2014. If the number of members joining the State Bar continues to grow, the growth in revenues from the membership fee will likely continue to outpace the growth in expenditures. In turn, the State Bar’s fund balances will also continue to grow.

Maintaining a reasonable fund balance would allow the State Bar to ensure that it charges its members appropriately for the services they receive. Other than a policy its board adopted in November 2013 that instituted a general fund policy of two weeks’ operating expenditures, which we believe is too low given the uncertainty of its membership fee revenue each year, the State Bar does not have policies or procedures that justify or govern its total fund balances. However, according to its former acting chief financial officer, the State Bar is currently developing these policies. The Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA)—a professional association of public officials dedicated to enhancing and promoting the professional management of government financial resources—cited a general best practice related to fund balances that could benefit the State Bar. Specifically, the GFOA noted that an appropriate fund balance in an entity’s general fund should be no less than two months of operating revenues or expenditures.

To provide the State Bar with an example of what its fund balances should be based on the GFOA guidance, we computed the equivalent of two months’ worth of expenditures the State Bar averaged over our six‑year audit period and compared the result to the State Bar’s 2014 fund balances. Because the State Bar’s 26 funds generally serve different purposes and are funded from different sources, we conducted this analysis by grouping these funds into the following four general categories based on their purpose and funding source:

- Funds that support the State Bar’s general operating activities, including its general fund, the San Francisco Building Fund, and the Technology Improvements Fund.

- Funds that provide a public benefit, such as indigent services and attorney assistance programs.

- Funds that are supported by a specific fee or their own revenue sources apart from the annual membership fee, such as the admission fee for the State Bar examination.

- Funds that are either legally restricted or otherwise unavailable, such as the Client Security Fund and Los Angeles Facilities Fund. Some of these funds we considered unavailable because they are invested in capital assets. As we show in Table 10, the State Bar’s 2014 fund balances exceed the GFOA’s recommended fund balances in all of the categories, and the State Bar maintains the majority of the excess fund balances in the fourth category of legally restricted funds or funds that are otherwise unavailable because they are invested in capital assets.

| Category 1 | Category 2 | Category 3 | Category 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Operating Activities | Indigent client services and attorney assistance | Funds Supported by Specific Fees or other revenue sources | Legally restricted or otherwise unavailable | |

| 2014 actual fund balance | $22.9 | $6.7 | $20.9 | $87.5 |

| Best practice fund balance | 10.8 | 3.4 | 4.6 | 3.9 |

| Difference | (12.1) | (3.3) | (16.3) | (83.6) |

| Number of months of operating expenses | 4 months | 4 months | 9 months | NA |

| Total fund balance available, categories 1 through 3 |

Sources: California State Auditor’s analysis of the State Bar of California’s audited financial statements for 2009 through 2014.

NA = Not applicable.

Based on our analysis, we believe the State Bar needs to evaluate the revenue it receives and the services it provides for the first three categories. In particular, the first category—general operating activities—exceeds the recommended fund balance by $12.1 million, and we believe this presents an opportunity for the State Bar to work with the Legislature to reassess the membership fees to better align with the State Bar’s actual operating costs so that the fund balances do not continue to increase.

The State Bar indicated that it has planned uses for the fund balances in the first category. For example, the acting executive director stated that the State Bar has approximately $7.3 million in building improvements planned over the next four years for its San Francisco building, including fire and life safety system upgrades; elevator modernization; and heating, ventilation, and air conditioning upgrades. Taking into consideration the State Bar’s planned projects, the acting executive director stated that the State Bar expects a deficit in available funds in the first category. Be that as it may, it is likely the State Bar would have been able to fully fund these improvements if it had not used some of its funds that support operating activities for the purchase and renovation of its Los Angeles building, as we discussed earlier in this chapter.

The fund balance for the second category indicates that the State Bar may be able to expand the services it currently provides that serve a public benefit. However, the acting executive director does not believe that this category contains excess funds that could potentially be available for additional programs—unless the revenue sources increase. Specifically, the acting executive director noted that a portion of the funds in this category are devoted to administering grants that help fund legal services programs serving indigent Californians, and to the extent that these revenue resources increase, the State Bar will administer the increased amount. In addition, he stated that funds in this category support the Lawyer Assistance Program and relations with local, national, and international bar associations. Nevertheless, this category contained a $6.7 million fund balance at the end of 2014—$3.3 million over the GFOA’s recommended best practice amount.

The fund balance for the third category suggests the State Bar may have opportunities to decrease the amounts it charges members for specific services or to expand the services it provides with these funds. In particular, this category exceeds the recommended fund balance by $16.3 million, or four and a half times the recommended best practice amount. Again, the State Bar does not believe it has excess funds in this category. For example, the acting executive director stated that the Admissions Fund—which receives support from various sources including applicant fees, fees for study aids, and interest income—has no excess funds because the State Bar directs them to the admissions process and the cost of this process continues to rise. However, because the State Bar used some of the funds in this third category to purchase the Los Angeles building, it may again choose to use them for purposes other than what the acting executive director described.

Even though the State Bar disagrees that it has excess available revenue in these three categories, the State Bar needs to conduct a thorough analysis of its revenues, operating costs, and future operational needs to support this assertion. However, as we described in Chapter 1, the State Bar has not conducted a critical piece of this analysis—a workload analysis—to determine the level of staffing needed in its discipline system. If the State Bar conducts a workload analysis that concludes it needs more staff to operate the discipline system, the State Bar should devote more of its monetary resources to accomplishing that goal. The State Bar should also examine its use of contractors and temporary employees, which provide more staffing flexibility but can be more costly than employing permanent staff, to ensure that those expenditures are necessary and justified.

Because the Legislature must authorize the State Bar to collect membership fees, which fund a significant portion of its operations on an annual basis, the type of long‑term planning we suggest is challenging. As mentioned in the Introduction, more than half of the State Bar’s general operating activities—including its discipline functions—are financed through membership fees. According to the acting executive director, the reality of the State Bar’s funding creates problems for long‑term planning, staff stability, and staff recruiting because the State Bar has no assurance of future annual revenues beyond the existing year, which in turn demands that the State Bar have funds on hand to cover a loss or decrease in funding. According to the acting executive director, any regular funding cycle that would give the State Bar certainty of funding for a multiyear period would enhance its ability to engage in longer‑term planning on staffing levels and other operational cost needs.

Recommendations

To ensure that it spends revenues from the membership fee appropriately, the State Bar needs to implement policies and procedures to restrict its ability to transfer money between funds that its board or state law has designated for specific purposes.

To ensure that it can justify future expenditures that exceed a certain dollar level, such as capital or IT projects that cost more than $2 million, the State Bar should implement a policy that requires accurate cost‑benefit analyses comparing relevant cost estimates. The policy should include a requirement that the State Bar present the analyses to the board to ensure that it has the information necessary to make appropriate and cost‑effective decisions. In addition, the State Bar should be clear about the sources of funds it will use to pay for each project.

To justify any future special assessment that the State Bar wants to add to the annual membership fee, the State Bar should first present the Legislature with the planned uses for those funds and cost estimates for the project for which the State Bar intends to use the special assessment.

To ensure that it adequately informs the Legislature about the status of the IT projects in its strategic plan, the State Bar should annually update the projects’ cost estimates, their respective status, and the funds available for their completion.

To ensure that the State Bar’s fund balances do not exceed reasonable thresholds, the Legislature should consider putting a restriction in place to limit its fund balances. For example, the Legislature could limit the State Bar’s fund balances to the equivalent of two months of the State Bar’s average annual expenditures.

To provide the State Bar with the opportunity to ensure that its revenues align with its operating costs, the Legislature should consider amending state law to, for example, a biennial approval process for the State Bar’s membership fees rather than the current annual process.

To determine a reasonable and justified annual membership fee that better reflects its actual costs, the State Bar should conduct a thorough analysis of its operating costs and develop a biennial spending plan. It should work with the Legislature to set an appropriate annual membership fee based upon its analysis. The first biennial spending plan should also include an analysis of the State Bar’s plans to spend its current fund balances.

We conducted this audit under the authority vested in the California State Auditor by Section 8543 et seq. of the California Government Code and according to generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives specified in the scope section of the report. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Respectfully submitted,

ELAINE M. HOWLE, CPA

State Auditor

Date: June 18, 2015

Staff:

John Baier, CPA, Audit Principal

Kathleen Klein Fullerton, MPA

Brianna J. Carlson

Matt Gannon

Joshua Hooper, CIA, CFE

IT Audit Support:

Michelle J. Baur, CISA, Audit Principal

Ben Ward, CISA, ACDA

Kim L. Buchanan, MBA, CIA

Richard W. Fry, MPA, ACDA

Shauna M. Pellman, MPPA, CIA

Legal Counsel:

Stephanie Ramirez‑Ridgeway, Sr. Staff Counsel

For questions regarding the contents of this report, please contact Margarita Fernández, Chief of Public Affairs, at 916.445.0255.