Chapter 1

Department Websites Do Not Fully Comply With State Accessibility Standards

Key Points

» The four department websites we reviewed are not fully accessible under applicable web accessibility standards. Many of the accessibility violations we identified are of critical severity, meaning that elements of these websites were completely inaccessible to users with disabilities.7

» Because of some critical accessibility violations that occur under certain conditions, users with disabilities are not able to complete core online tasks that three departments offer. For example, a violation on the State of California Franchise Tax Board’s (Franchise Tax Board) website prevents users who cannot use a mouse from creating an online account—a required step in submitting tax returns online.

» California’s web accessibility standards are out of date and do not reflect current best practices for ensuring accessibility for persons with disabilities. The most up-to-date standards are designed to be consistent with future technologies. Thus, we believe that it is important for the Legislature to amend state law to require compliance with more up-to-date standards issued by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C).

Department Websites Are Not Fully Accessible Under State Mandated Standards

We evaluated the websites of four departments to determine whether the sites comply with web accessibility standards designed to ensure that persons with disabilities can access and navigate those sites. As discussed in the Introduction, California requires that state governmental entities’ websites comply with Section 508 of the federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973, as amended (Section 508) and that agencies reporting to the governor and state chief information officer must comply with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) version 1.0.8 To evaluate the accessibility of each department’s website, we identified a specific service each department offers through its website and reviewed the key pages of the department’s website that support that service against the relevant criteria for each department.9 In performing this review, our web accessibility consultant (consultant) identified violations of accessibility standards that occurred on individual web pages, as well as common accessibility violations—violations that occurred in similar or identical ways across multiple pages. One example of a common violation is an accessibility issue located in a website’s header or footer, which would be present on many web pages throughout the site. To avoid double-counting common violations, we counted each of them as a single violation affecting a single page, although each of these violations represents issues occurring across multiple pages. Table 5 shows the total number of pages we reviewed at each department as well as the number of those pages on which our consultant found individual and common violations.

What a Violation’s Severity Means for Individuals With Disabilities

Critical: Makes underlying content completely inaccessible to users.

Serious: Results in serious barriers for users, making some content inaccessible.

Moderate: Results in some barriers to users, but does not prevent them from accessing fundamental content.

Source: Our web accessibility consultant’s definitions of the severity levels assigned to each accessibility violation that testing identified on departments’ websites.

All four department websites we reviewed have violations of accessibility standards that make it difficult for users with disabilities to successfully navigate the sites, but the violations vary in how severely they affect users. Our consultant assigned a severity level to each violation based on its effect on a user’s ability to interact with the specific element of the web page that contained the violations. The text box defines the different levels of severity. A violation of critical severity is one that makes the underlying content completely inaccessible to persons with disabilities. One example of a critical violation affecting persons with disabilities who navigate the Internet by keyboard alone would be if a website did not provide visual cues to those users indicating where on a web page they were navigating. Such a violation would make it prohibitively difficult for these users to navigate a website. By comparison, a moderate violation, such as a violation in which a decorative image is improperly programmed for screen readers, creates barriers for individuals with disabilities but does not prevent them from accessing the web page’s content. In this particular example, the violation could cause a screen reader user to be aware of that image but not know that the image was purely decorative and did not contain useful information. As a result, the violation could confuse the user, but would not make the page’s content completely inaccessible. Table 6 shown below shows the number and proportion of violations at each severity level found at each department. The departments varied in the overall severity of their accessibility violations, but many of the accessibility violations we identified are of critical severity, meaning that elements of these websites were completely inaccessible to users with disabilities.

| California Community Colleges | California Department of Human Resources | Covered California | State of California Franchise Tax Board | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pages reviewed | 58 | 78 | 57 | 70 |

Pages with distinct violations* |

27 |

38 |

55 |

40 |

Pages with common violations† |

3 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

Source: California State Auditor’s review of the results of accessibility testing conducted by our web accessibility consultant (consultant).

Note: For the purposes of this table, we use the term violation to mean noncompliance with an accessibility standard a department’s website was expected to conform to because of state law or a grant or contract agreement. In this table, we did not include violations of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 1.0 that our consultant advised are so out of date that department efforts to comply with them might be inefficient. However, the table does include violations of WCAG 1.0 that were not outdated.

* Distinct violations of accessibility standards our consultant identified that occur on individual web pages.

† Common violations of accessibility standards are violations that are present in similar or identical ways across multiple pages throughout the site. In this table, we report each common violation as occurring on a single web page, even though the violation affects each page on the website where it is present. As a result, the number of pages with violations at each department is understated. Additionally, because distinct and common violations can both occur on the same web page, the number of pages with distinct and common violations in the table cannot be summed to calculate the total number of web pages with one or more violations at a department.

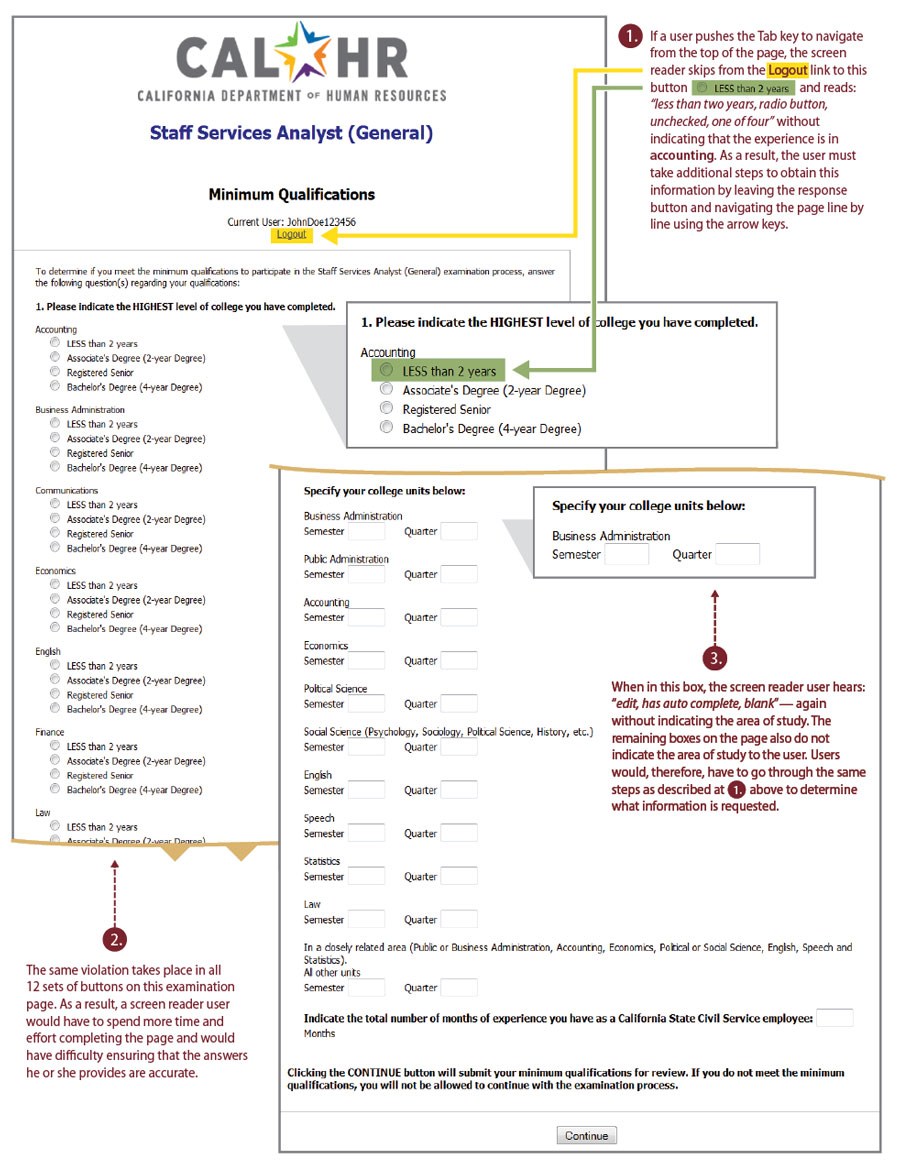

One critical violation on the California Department of Human Resources’ (CalHR) Careers in California Government website (jobs site) concerns the areas on the exam form for state employment as a staff services analyst in which users must enter responses to exam questions. These areas were not always properly labeled so that they were connected to the corresponding exam questions. When these areas are properly labeled, a visually impaired user’s screen reader will read the question the user needs to answer as he or she tabs into the response area. Instead, on the exam we reviewed, persons using screen readers would need to leave the unlabeled response area and use other methods, such as browsing the surrounding text on the web page line by line with the keyboard’s arrow keys, to try to determine what information they should enter. Before entering the information, the user would then need to navigate back into the response area using the Tab key. However, because the area was not properly labeled, the user could not be certain the response area was the one he or she left earlier. A similar critical violation on the same exam affects buttons that those taking the exam must use to answer questions. Both of these violations are common violations and occur throughout the exam we reviewed. Figure 3 illustrates how often these violations occur on a sample page of the exam.

| California Community Colleges | California Department of Human Resources | Covered California | State of California Franchise Tax Board | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity | Distinct Violations* | Common Violations† | Distinct Violations* | Common Violations† | Distinct Violations* | Common Violations† | Distinct Violations* | Common Violations† |

Critical |

26 | 2 | 26 | 7 | 287 | 18 | 17 | 7 |

Serious |

64 | 2 | 384 | 16 | 644 | 15 | 20 | 4 |

Moderate |

6 | 6 | 29 | 0 | 1,425 | 1 | 54 | 1 |

Source: California State Auditor’s review of the results of accessibility testing conducted by our web accessibility consultant (consultant).

Note: For the purposes of this table, we use the term violation to mean noncompliance with an accessibility standard a department’s website was expected to conform to because of state law or a grant or contract agreement. In this table, we did not include violations of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 1.0 that our consultant advised are so out of date that department efforts to comply with them might be inefficient. However, the table does include violations of WCAG 1.0 that were not outdated.

* Distinct violations of accessibility standards our consultant identified that occur on individual web pages.

† Common violations of accessibility standards are violations that are present in similar or identical ways across multiple pages throughout the site. We report each common violation as occurring only once in this table, even though each represents multiple individual violations occurring throughout the respective website.

As a result of these violations, users taking the exam with the assistance of a screen reader could be forced to spend more time and effort to complete it than if the exam complied with state accessibility standards. Further, because it was unclear what the questions require, the risk is higher that users may inadvertently respond to exam questions with incorrect information. Incorrect answers to exam questions could cause applicants who would otherwise have attained eligibility for employment to miss an employment opportunity. The development supervisor for CalHR’s jobs site indicated that the exam we reviewed was an older exam and that he was not aware of it ever having been tested for accessibility.

Figure 3

California Department of Human Resources, Staff Services Analyst Exam Accessibility Violations

Source: California Department of Human Resources’ online staff services analyst exam.

Staff at CalHR were aware of similar issues affecting another job exam over a year ago but did not fully address all of the barriers in that exam or conduct a review of other exams at that time. In February 2014 the CalHR web manager reviewed an employment exam for an office technician position after the department received a complaint about the exam. After his review, the web manager noted that questions on the exam were missing labels, making it difficult for screen reader users to know how to respond. However, when we asked about these issues in March 2015, the development supervisor for CalHR’s jobs site indicated that only some of the violations on that exam had been addressed. The supervisor stated that he assumed that the issues had been fixed since the developer for that job exam had been notified of the issues. The supervisor also stated that after discovering the issues with this exam, CalHR did not review other exams. If CalHR had done so, it may have known that similar issues existed on the exam we reviewed as part of this audit. Instead, CalHR was unaware that this exam had accessibility violations until we found them.

Community Colleges has already addressed a critical violation on its OpenCCCApply website (online application) that blocked some users from knowing whether they had completed all required components of the online college application. The online application form contains tabs for each page of the application, and these tabs include check mark symbols that indicate the user has successfully completed that page. In addition, the online application allows users to pass through pages of the application without fully completing them. However, at the time of our review the check mark symbols were missing text alternatives that screen readers need in order to interpret them for a visually impaired user. Therefore, this efficient way of knowing whether an application is complete was not available to screen reader users. As a result, if a screen reader user had intentionally or unintentionally skipped over a portion of the application, he or she would not be alerted that the application was incomplete until the last application page. Further, these users would have greater difficulty than others in determining which specific pages were missing required information, as they might have had to review the entire application to identify where exactly information was missing. The database that Community Colleges uses to track issues with its online application shows that a user complained about this violation in February 2015, shortly after our review of the online application the previous month. When we asked Community Colleges about the violation, the technology center’s chief technology officer stated that the feature with the check mark symbols had been part of the online application since it was first released in November 2012 but was not tested for accessibility. To its credit, after receiving the complaint, Community Colleges addressed the violation in an update to the online application in February 2015. However, had the department appropriately tested the application for accessibility, it could have corrected the problem earlier and prevented it from potentially affecting college applicants.

Our consultant also identified significant numbers of serious accessibility violations at all four departments. Although these violations do not make content completely inaccessible to persons with disabilities, they present serious barriers to using the site in a way that is comparable to the experience of persons without disabilities. For example, our consultant found a serious violation on Covered California’s website that prevents users from skipping over repetitive content each time they visit a new page on the site. Section 508 standards require that websites provide users with a method for skipping repetitive navigation links. Such links may appear at the top of each individual web page on a website. This standard helps ensure that websites are accessible to persons with disabilities who navigate the Internet with the keyboard alone, such as persons with motor disabilities. Covered California’s site provides a link that, if placed correctly on the site, would allow users to skip to the main content of each page. However, due to where this link is currently placed, keyboard-only users must navigate through all the repetitive links in the website’s header before they can access it, unnecessarily adding to the time it takes those users to access the main content of the web page. Because the link appears after all the repetitive content on the page, it provides no practical benefit to users and does not satisfy the Section 508 requirement.

After analyzing the results of our consultant’s review, we provided each department with supporting details about each violation our consultant identified, including those we report on in this chapter. Subsequently, Covered California, CalHR, and Franchise Tax Board claimed that they began addressing some of the violations we identified. However, as described in the Introduction, our review did not include a comprehensive examination of any of the reviewed departments’ entire web presence. Instead, we focused on the pages in support of a service each department offers online. It is possible that the types of violations we describe in this section, as well as violations that were not present in the reviewed websites, exist in other areas of each department’s online presence that we did not review. Departments could guard against the risk that similar accessibility violations exist elsewhere on their websites by reviewing the violations we found, noting whether and where they are likely to occur throughout the rest of their online presence, and following up to correct the violations where they do occur.

Some Accessibility Violations We Found Present Particular Burdens to Users

For three of the department websites we reviewed, certain critical accessibility violations could, under some circumstances, prevent users from completing core online tasks. As discussed in the previous section, our consultant defined critical accessibility violations as violations that make the underlying content completely inaccessible to persons with disabilities. Moreover, we found that particular critical violations at Community Colleges, Covered California, and Franchise Tax Board could, under certain conditions, prevent users from accessing the content they need to complete the core online tasks we tested at those departments. As with the other accessibility violations we discuss in this report, these violations affect users with specific types of disabilities, and because our consultant used a specific model and version of web browser and screen reader when performing the accessibility testing, users of different models or versions may not experience these violations in the same way and may be able to navigate past them.10 However, our consultant used the most recent version of the Mozilla Firefox (Firefox) web browser that was available at the time to test the accessibility of the departments’ websites. Firefox is a free browser software used by more than 500 million people worldwide. Therefore, the violations our consultant found are likely to affect a significant number of disabled users.

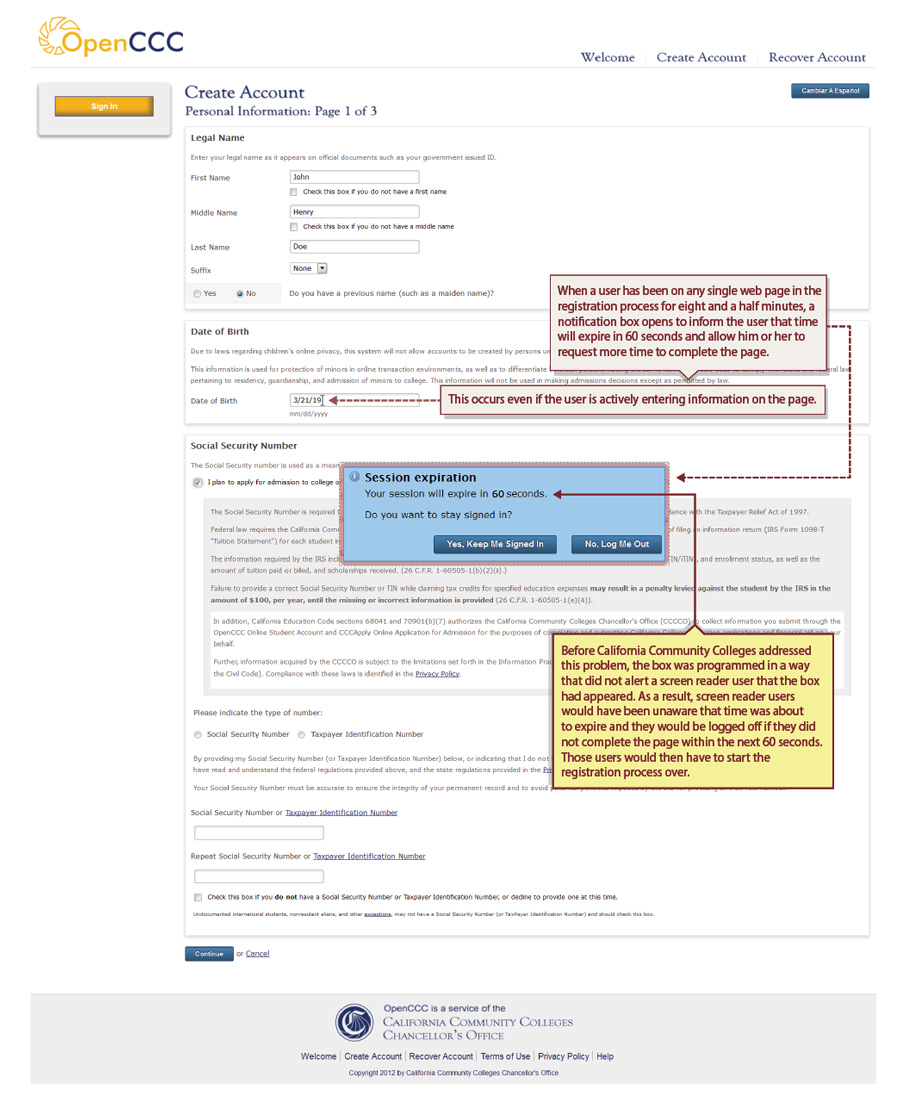

In order to complete Community Colleges’ online application, users must first register for an account. To register, users are required to complete a series of pages by entering personal information and establishing a password and security questions. If a user takes more than eight and a half minutes to complete any of these pages, the application opens a time‑out notification indicating that the application will log the user off in another 60 seconds unless he or she selects a button inside the notification box indicating that he or she wants to continue completing the account registration. This occurs even if the user is actively navigating around a page and entering information. If time expires, the application logs the user out of the registration, and the information the user has entered up to that point is lost. Users must restart the registration process from the beginning if they are timed out in this manner.

This time-out notification process was inaccessible for some visually impaired users at the time of our review. Due to the way the notification box was programmed, screen reader software did not identify the box when it appeared, and therefore users were not alerted to its presence. As a result, screen reader users would have been unaware that time was about to expire, and they would be logged off if they did not complete the application page in the following 60 seconds. At that point, these users would have to begin the registration process again and would experience the same problem again if they did not more quickly complete the registration pages. Figure 4 shown below illustrates the issue screen reader users would have with the time-out notification. Because registration is a required step in the online application process, this violation could have prevented some screen reader users from being able to submit an application to college.

Figure 4

California Community Colleges, Account Creation Accessibility Violation

Source: California Community Colleges’ OpenCCCApply online account creation page.

Community Colleges has now addressed this accessibility violation, but the violation illustrates shortcomings in its approach to accessibility testing. The Community Colleges technology center’s chief technology officer indicated that the time-out feature was added to the online application in December 2014 but that it was not tested for accessibility before being made available to the public. As a result, he became aware of this issue only after receiving a complaint from a screen reader user in February 2015. The chief technology officer also stated that all such updates to the website should include accessibility testing, but acknowledged that the technology center did not have a formal plan for completing accessibility testing on updates to its online application. We verified that, since discussing the issue with Community Colleges, the violation has been addressed and the notification box is functioning properly for screen readers.

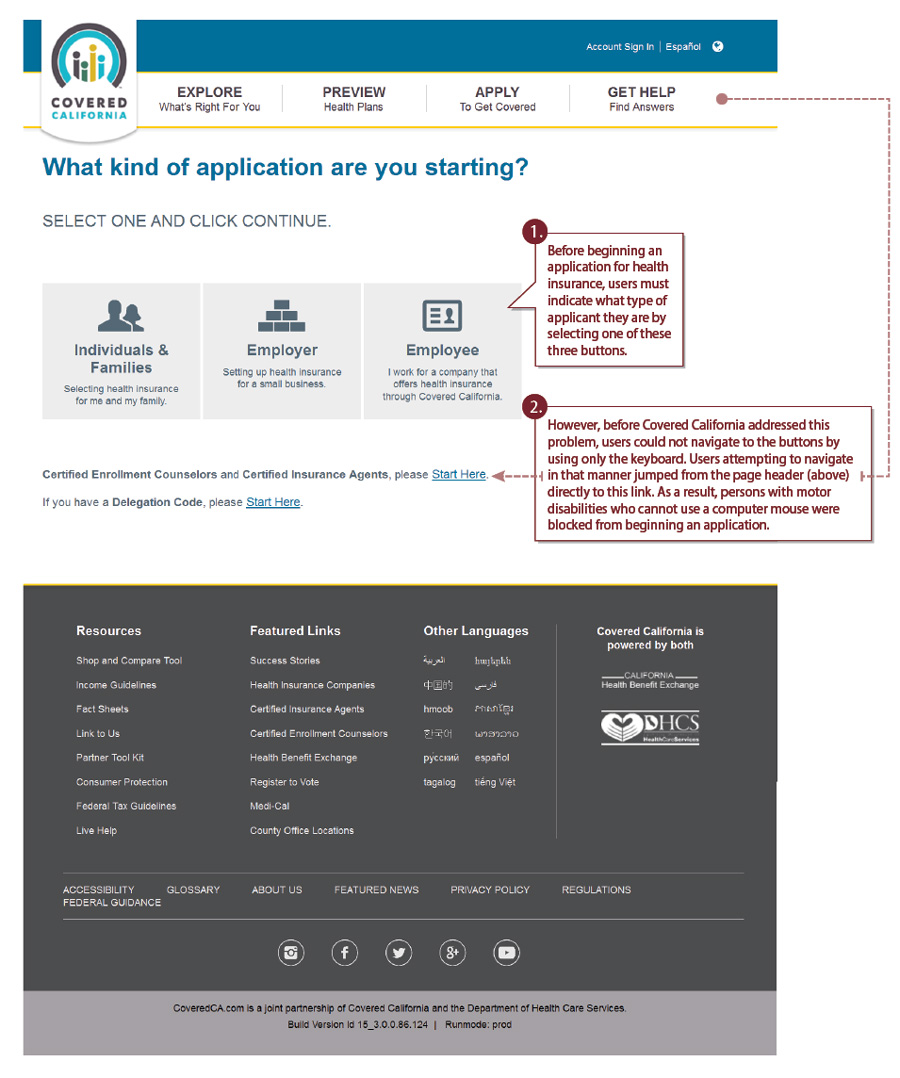

At Covered California, our review identified a critical violation that prevented keyboard-only users from applying for health insurance on the Covered California website. Figure 5 shown below illustrates this violation. Before starting an application for health insurance, users must identify what type of applicant they are: individual or family, employer, or employee. The Covered California website provides a button for each of these three options. However, users were not able to navigate to those buttons using the keyboard alone. As a result, persons with motor disabilities who are unable to use a computer mouse could not begin the application process.

At the time of our review in February 2015, Covered California had recently made changes to this page of its website. However, Covered California did not test these changes for how they might affect the accessibility of its website. As a result, it was not aware that the new version of the page was inaccessible to users with certain disabilities and blocked those users from applying for health insurance. After we brought this violation to its attention, Covered California fixed the violation through an update to its website in May 2015.

Figure 5

Covered California, Application Accessibility Violation

Source: Covered California’s online account creation page.

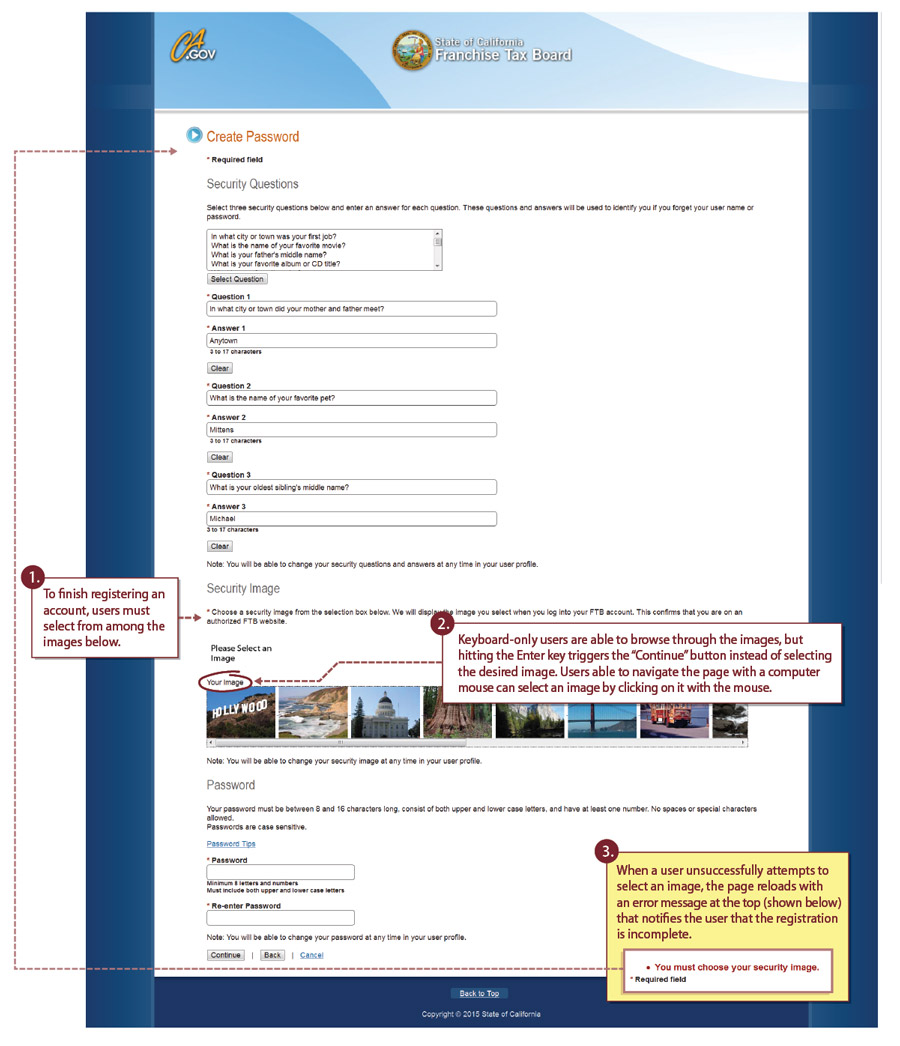

Our review also identified a violation in the registration process for Franchise Tax Board’s CalFile application that could prevent some users from being able to complete and file their California tax returns online. When registering for an account, users must choose a security image that will be associated with their account going forward. Users with motor disabilities who navigate the Internet by using only a keyboard are unable to select this required image. Specifically, when one of these users navigates to an image and presses the Enter key to select it, the website submits the incomplete registration page rather than selecting the image. The website then notifies the user that he or she must select an image in order to complete the registration process. Figure 6 illustrates this error. If users are unable to register with the Franchise Tax Board, they cannot use CalFile to file their tax returns online.

Franchise Tax Board’s accessibility lead analyst stated that the account registration software is distinct from the CalFile software and has not been tested for accessibility since December 2012. Results from the 2012 testing indicate Franchise Tax Board knew about some keyboard navigation issues at that time but did not identify this particular violation. The accessibility lead analyst stated that she could not be sure why her test report did not identify this issue but suggested that changes to the software or web browser updates since 2012 could have caused it. She also stated that keyboard users do not encounter this violation when using web browsers other than the browser our consultant used to test the website. Nonetheless, as we described in the previous section, our consultant used a widely used web browser when conducting its testing. As a result, violations affecting this browser could affect many persons with disabilities.

Another critical violation our consultant found on Franchise Tax Board’s CalFile application could prevent some persons with disabilities from submitting their completed tax returns as the website instructs. Before submitting completed tax returns online, Franchise Tax Board directs users to review a PDF file that summarizes the information they have entered throughout the return process and certify that it is accurate. However, the PDF file that Franchise Tax Board presents to users is not fully accessible, preventing visually impaired screen reader users from being able to review the tax form. As a result, those users cannot verify that they have entered all their tax information correctly before submitting their tax returns. If users submitted their tax returns without reviewing the accuracy of the information, they would violate the Franchise Tax Board’s instructions and risk submitting an inaccurate return.

Figure 6

State of California Franchise Tax Board, Account Creation Process Accessibility Violation

Source: State of California Franchise Tax Board’s online account creation page

Despite knowing about this accessibility issue for more than two years, Franchise Tax Board has not implemented a solution that would provide comparable access to users with disabilities. Accessibility testing documents at Franchise Tax Board indicate that staff have known about this violation since at least December 2012 and are aware of how it affects users with disabilities. According to the manager who oversees CalFile, this issue was not given a higher priority because Franchise Tax Board believed that a disabled user could seek assistance from a third party to review the tax form, and it assumed that users would not submit their tax returns online unless they had found a way to review its content. Although users may be able to seek outside assistance in filing their taxes, placing this requirement on disabled users does not provide them comparable access to CalFile, which is a stated purpose of Section 508. The manager indicated that Franchise Tax Board has considered modifying this step in the online filing process so that users would not need to rely on the PDF copy of the tax form, but it has not yet done so. The manager also stated that Franchise Tax Board had hoped to find a way to adapt the PDF so it would be accessible, but it has not been able to do that. An email provided by Franchise Tax Board’s accessibility lead analyst indicates that in November 2014 staff at Franchise Tax Board attempted to make the PDF accessible but were unsuccessful in that effort. According to the manager, Franchise Tax Board plans to address this accessibility violation when it releases its next version of CalFile in January 2016.

California’s Accessibility Standards Have Not Been Modernized

California’s website accessibility standards are outdated and do not reflect current best practices for ensuring comparable access for persons with disabilities. As shown in Figure 1 on the Introduction page, the W3C updated its WCAG standards in 2008 to version 2.0. The Information Organization, Usability, Currency, and Accessibility Working Group, which recommended California adopt WCAG 1.0 in 2006, recognized that technology changes rapidly and in its recommendations document emphasized the importance of evaluating and updating the State’s accessibility standards as needed. However, California has not revised its 2006 policy that requires websites to comply with WCAG 1.0 standards for departments and agencies reporting to the governor and the state chief information officer.

According to the W3C, the WCAG 2.0 standards have certain key advantages over the 1.0 version. Specifically, it has stated that the WCAG 2.0 standards apply more broadly than the 1.0 standards to different types of web technologies and are also designed to be consistent with future technologies. The W3C has also stated that the 2.0 standards are more testable, allowing website providers to better ensure that their sites are accessible. In contrast, some of the WCAG 1.0 standards are unclear or difficult to enforce, according to the federal Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board (Access Board), which issued the Section 508 standards. For example, one standard requires websites to use the clearest and simplest language appropriate for the content of the site. The Access Board did not include this as a Section 508 standard; instead determining that this standard was difficult to enforce because a requirement to use the simplest language can be very subjective.

The WCAG 2.0 standards specify testable criteria that organizations can use to determine whether their websites conform to the standards. For example, one such criterion is that text on a web page can be doubled in size without using assistive technology and without loss of the page’s content or functionality. There are three conformance levels in the WCAG 2.0 standards: A (the lowest level of conformance), AA, and AAA (the highest level of conformance). A website conforming to the AAA level of the WCAG 2.0 standards must meet more stringent accessibility criteria than a website that conforms to either the A or AA level. The W3C does not recommend that organizations adopt the AAA conformance level as policy for their entire website because it is not currently possible to satisfy the related criteria for some types of web content.

The Access Board has considered adopting the WCAG 2.0 standards as a replacement for the Section 508 standards. In 2010, the Access Board issued an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking that proposed updating the existing Section 508 standards for web accessibility with slightly modified versions of the WCAG 2.0 standards. In response to public concern that the slightly modified standards were potentially confusing, the Access Board later reissued the draft proposed rule and incorporated the WCAG 2.0 standards in their entirety up to the AA conformance level. More recently, in February 2015, the Access Board issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking that incorporated the WCAG 2.0 standards, at the AA level of conformance, as a replacement for the existing Section 508 standards. As of April 2015, the Access Board was scheduled to close public comment on this proposed rule on May 28, 2015.

To further compare the WCAG 1.0 and 2.0 standards, we reviewed the departments’ websites against the WCAG 2.0 standards at the AA conformance level. We did not identify any state law or policy that would require the departments we reviewed or any other state department to meet the WCAG 2.0 standards. Nonetheless, we found that the vast majority of violations of the Section 508 and WCAG 1.0 standards also represent missed opportunities for accessibility under WCAG 2.0. For example, earlier in this chapter we described a violation on a CalHR employment examination where, due to improper labeling, screen reader users would not have exam questions read aloud to them. This was a violation of a WCAG 1.0 standard that CalHR is currently required to meet. However, the labeling problem also does not meet a WCAG 2.0 standard. Our consultant advised us that some of the WCAG 1.0 standards violated do not perfectly align with the corresponding 2.0 standards. As a result, it is possible that departments, in complying with current state standards, could apply outdated techniques for providing accessible websites that would leave them short of the WCAG 2.0 standard. In other words, despite the overlap we observed between many WCAG 1.0 and 2.0 standards, there is still benefit in clearly defining which of these two standards state departments should be required to meet.

We believe it is important that California update its accessibility requirements to bring them in line with the most up-to-date accessibility standards. Currently, that would mean requiring state departments to comply with the WCAG 2.0 standards. According to the W3C, most websites that conform to the WCAG 1.0 standards should not require significant changes to comply with WCAG 2.0. Therefore, the additional cost of any change to the state accessibility standards is likely to be minimal for departments that already comply with the current state requirements. Because changes in technology are ongoing, it is also important that the State make every effort to prevent its accessibility standards from again becoming outdated in the future. CalTech, as the State’s lead department for matters related to information technology, could help the State keep its accessibility policy up to date by monitoring WCAG standards and alerting policymakers to any further revisions the W3C makes to those standards. After we discussed this matter with her, CalTech’s chief deputy director of policy stated that she sees a role for CalTech in monitoring emerging web accessibility standards and that CalTech could notify the Legislature in the future if commonly accepted standards changed significantly enough that California should adjust what standards it requires.

Recommendations

Legislature

To maximize the accessibility of California’s websites, the Legislature should amend state law to require that all state websites conform to WCAG 2.0 standards at compliance level AA in addition to the Section 508 standards.

To help ensure that California’s accessibility standards remain current, the Legislature should amend state law to require CalTech to monitor commonly accepted accessibility standards and apprise the Legislature of any changes to those standards that California should adopt.

Departments

To ensure that they address barriers to the accessibility of their websites for persons with disabilities, each of the four departments should, no later than December 1, 2015, correct the accessibility violations we found during our review.

No later than December 1, 2015, each department should develop a plan to determine whether the accessibility violations we identified exist on other portions of their online presence that we did not include in the scope of our review. At Community Colleges this should include any web presence managed by its technology center. Once this plan is executed, the departments should correct violations wherever they find them and do so no later than June 1, 2016.

Footnotes

7 For the purposes of this report, we use the term violation to mean noncompliance with an accessibility standard a department’s website was expected to conform to because of state law or a grant or contract agreement.Go back to text

8 The WCAG 1.0 standards are individual testable checkpoints that organizations can use to review their websites for accessibility.Go back to text

9 Covered California is not subject to the policies issued by the state chief information officer, who is the director of the California Department of Technology (CalTech), and as such would not be required to follow WCAG 1.0. We assessed Covered California against Section 508 standards and a more up-to-date version of the WCAG standards that we discuss in the Introduction—WCAG 2.0. This is because Covered California’s contract with the vendor that developed and maintains the California Healthcare Eligibility, Enrollment, and Retention System required that the vendor provide a product that complied with accessibility standards issued by the W3C. At the time Covered California entered into this agreement, the most up-to-date version of those standards was WCAG 2.0. Additionally, it is unclear whether California Community Colleges (Community Colleges) is required to follow policies issued by the state chief information officer. However, the Community Colleges’ Chancellor’s Office requires that web-based materials developed by its technology center comply with WCAG 1.0 standards. Accordingly, we assessed Community Colleges’ online application against those standards.Go back to text

10 See the Scope and Methodology table, Objective 5(a) on the Introduction page, for details on the software our consultant used.Go back to text