CalOptima Health

It Has Accumulated Excessive Surplus Funds and Made Questionable Hiring Decisions

May 2, 2023

2022-112

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of certain aspects of the budget, services and programs, and organizational changes of the Orange County Health Authority, referred to as CalOptima Health (CalOptima). CalOptima is the sole Medi-Cal managed care plan in Orange County and serves nearly one million members. We determined that CalOptima accumulated surplus funds it should have used to improve services, retained a larger share of funds obtained through a process known as intergovernmental transfer (IGT) than other managed care plans we reviewed, and did not follow best practices when hiring for some executive positions.

CalOptima had accumulated more than $1.2 billion in unrestricted funds as of June 2022. It set aside $570 million of these funds as a reserve, which we determined was prudent, but the remaining $675 million represent surplus funds. An Orange County ordinance requires CalOptima to implement a financial plan that provides for using surplus funds on specific purposes, such as improving benefits, but CalOptima does not have a plan for spending all of its surplus funds and has struggled to use them in a timely manner. CalOptima also retained a larger share of IGT funds than other managed care plans we reviewed. Although it allocated a significant portion of its retained IGT funds for health care initiatives focused on members experiencing homelessness, it did not consistently monitor the effective use of those funds.

CalOptima’s executive turnover rate was higher than those of other managed care plans we reviewed, and it has hired several executives in recent years. However, it did not follow best practices when hiring three of six executives we reviewed, and one of its former board members may have violated state law when he entered into an employment contract to serve as the organization’s chief executive officer. CalOptima lacked a written policy that could have guided its approach to hiring in these instances. As a result of its practices, CalOptima has limited its ability to attract and select the most qualified candidates, and it has opened itself to criticism about the objectivity, appropriateness, and transparency of its hiring process.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CMS | Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

| CRDD | Capitated Rates Development Division |

| DHCS | Department of Health Care Services |

| GFOA | Government Finance Officers Association |

| HHI | Homeless Health Initiatives |

| HR | human resources |

| IGT | intergovernmental transfer |

Summary

California participates in the federal Medicaid program through its California Medical Assistance Program, known as Medi‑Cal. In Orange County, the Orange County Health Authority, referred to as CalOptima Health (CalOptima), is the sole Medi‑Cal managed care plan and serves nearly one million members, the majority of whom are beneficiaries of Medi‑Cal. CalOptima’s funding comes primarily from the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), which makes monthly payments to CalOptima based on per‑member rates for the provision of covered services. A process known as intergovernmental transfer (IGT) allows DHCS to increase the rates paid to managed care plans like CalOptima using federal matching funds. The IGT process involves a partnership between managed care plans and other government entities (funding partners). CalOptima’s board of directors (board) directed it to implement this IGT process in 2011. Since then, CalOptima has continued to use the IGT process, and it currently has five funding partners.

CalOptima Has Accumulated Surplus Funds It Should Have Used to Improve Services

As of June 2022, CalOptima had accumulated more than $1.2 billion in unrestricted funds. An Orange County ordinance requires CalOptima to implement a financial plan that includes the creation of a prudent reserve and provides that if surplus funds accrue they shall be used for specified purposes such as improving benefits. CalOptima’s board designated an amount for its reserve that is consistent with an established practice for government reserves, and CalOptima has set aside sufficient funds to meet the board’s requirements. However, beyond satisfying this reserve requirement, CalOptima had accumulated an additional $675 million of surplus funds as of June 2022. Notwithstanding the requirements in the Orange County ordinance, CalOptima’s reserve policy does not specify what it will do with such surplus funds, and it has struggled to spend them in a timely manner.

See our recommendations for improving this area of CalOptima’s operations.

CalOptima Retained a Larger Share of IGT Funds Than Other Managed Care Plans

Until recently, CalOptima retained approximately 30 percent of IGT funds, substantially more than the percentages agreed to by other managed care plans we reviewed and their funding partners. As of June 2022, CalOptima held $90 million in unused IGT funds. CalOptima allocated a significant portion of IGT funds for health care initiatives focused on members experiencing homelessness, but it did not consistently monitor the effective use of those funds.

See our recommendation for improving this area of CalOptima’s operations.

CalOptima Did Not Follow Best Practices When Hiring for Some Executive Positions

A former CalOptima board member may have violated a state law that prohibits public officials from being financially interested in certain contracts when he entered into an employment contract with CalOptima to serve as its chief executive officer (CEO). In addition, CalOptima does not have a written policy describing its hiring process. CalOptima hired a significant number of new executives in recent years, but for three of the six executives we reviewed, it did not follow the hiring process its human resources department described to us, and in some instances its actions were not consistent with its publicly stated plans for hiring executives. For example, it did not conduct national searches for two consecutive CEOs, as it said it would. By not doing so, CalOptima’s board limited its ability to attract and select the most qualified candidates and opened itself to criticism about the objectivity, transparency, and appropriateness of its hiring process.

See our recommendations for improving this area of CalOptima’s operations.

Other Areas We Reviewed

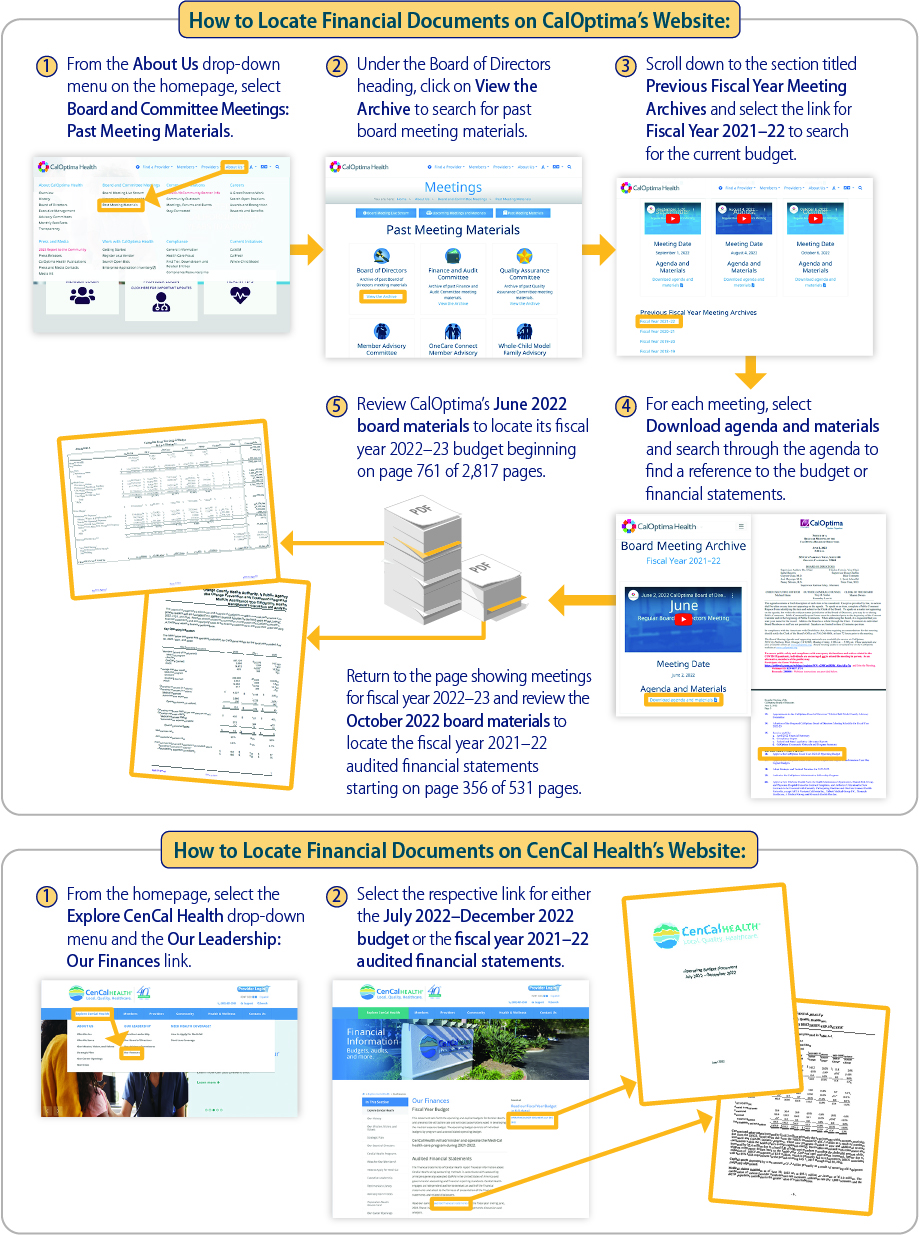

We also reviewed other areas of CalOptima’s operations, including its efforts to investigate reports of misconduct and ensure an atmosphere free from fear of retaliation, the actions it has taken to ensure timely access to care, and the accessibility of financial information on its website.

See our recommendations for improving one of these areas of CalOptima’s operations.

Agency Response

CalOptima stated that it cannot fully concur with all of our findings and recommendations because the time frame of the audit does not account for recent leadership actions over the past year. It also stated that it has already rectified many of the changes recommended in the audit, and it concurred or partially concurred with each of the individual findings.

We did not make recommendations to address findings that CalOptima demonstrated it had already resolved, as we explain in our comments on CalOptima’s response to our report.

Introduction

Background

The federal Medicaid program, which the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) oversees, provides medical assistance to certain low‑income individuals and families who meet eligibility requirements. California participates in the federal Medicaid program through its California Medical Assistance Program, known as Medi‑Cal. California’s Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) is the state agency responsible for administering Medi‑Cal, and state law identifies county welfare departments as the agencies responsible for Medi‑Cal’s local administration.

Key Facts About CalOptima

(October 2022)

| Fiscal year 2022–23 budgeted revenue | $4 billion |

| Fiscal year 2022–23 budgeted expenses | $4 billion |

| Total number of members | 938,000 |

| Number of Medi-Cal members | 920,000 |

| Provider network | 1,500 primary care physicians 9,200 specialists |

Source: CalOptima’s website and budget documents.

In 1993 Orange County created the Orange County Health Authority, referred to as CalOptima Health (CalOptima), and it is the sole Medi‑Cal managed care plan in Orange County. A managed care plan is a health care delivery system, such as a health maintenance organization, that typically receives a flat prepaid rate for each member enrolled in the plan and provides services to those members through a defined network of health care providers. As established in Orange County ordinance, CalOptima’s purpose is to negotiate exclusive contracts with DHCS and arrange for the provision of health care services to qualifying individuals in the county who lack sufficient annual income to meet the cost of health care. Its stated mission is “to serve member health with excellence and dignity, respecting the value and needs of each person.” Governance of CalOptima is vested in a board of directors (board) consisting of 10 individuals who are each required to have a commitment to a health care system that seeks to improve access to high‑quality health care for those CalOptima serves. As the text box shows, nearly all of CalOptima’s members are Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. CalOptima offers additional programs that serve a smaller number of members who qualify for both Medi‑Cal and Medicare.

Funding for Medi-Cal

Both the federal and state governments fund the costs of Medi‑Cal. As a Medi‑Cal managed care plan (managed care plan), CalOptima’s revenue is primarily provided by DHCS, as Table 1 details, in the form of payments that include money from both state and federal sources. DHCS data indicate that, on average, about 30 percent of the funds that DHCS paid to CalOptima during the period we reviewed were provided by the State and 70 percent were provided by the federal government.Although it was not possible to fully reconcile DHCS’s data to CalOptima’s financial statements, the difference is less than 3 percent of the proportion of state or federal funds. In addition to this difference, according to the chief of DHCS’s Capitated Rates Development Division, the data do not reflect all of the payments that DHCS will eventually make for these periods, especially for more recent fiscal years. He also stated that the data do not reflect rate revisions that are in the process of being made, system updates that will affect the split of federal and state funding, or some adjustments to payments that are processed outside of this system. CalOptima was not able to confirm these amounts. CalOptima’s controller stated that he is unable to say how much of the funding CalOptima receives from DHCS is state funding and how much is federal funding. This is likely because, according to the assistant chief of DHCS’s Capitated Rates Development Division (CRDD assistant chief), DHCS does not distinguish for the plan what portion of the payments is from state funds and what portion is from federal funds. Table 1 also shows the amount of funds CalOptima received from CMS. Those funds were for the additional programs serving a smaller number of members who qualify for both Medi‑Cal and Medicare that we mention above.

Table 1

Most of CalOptima’s Revenue Is Received in the Form of Combined State and Federal Funds

| CALOPTIMA FUNDING SOURCES | FISCAL YEAR 2019–20 | FISCAL YEAR 2020–21 | FISCAL YEAR 2021–22 | FISCAL YEAR 2022–23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State and Federal Funds Received From State Agencies (DHCS)* | $3.521 billion (92%) |

$3.804 billion (92%) |

$3.865 billion† (91%) |

$3.652 billion† (91%) |

| Federal Funds Received From a Federal Agency (CMS) | 312 million (8%) |

344 million (8%) |

360 million (9%) |

350 million (9%) |

| Private Funds | ‡ |

‡ | None | None |

| Totals | $3.833 billion | $4.148 billion | $4.225 billion | $4.002 billion |

Source: CalOptima’s audited financial statements for fiscal years 2019–20 through 2021–22, CalOptima’s fiscal year 2022–23 budget, and interviews with CalOptima and DHCS staff.

* When DHCS pays a managed care plan such as CalOptima, DHCS does not distinguish for the plan what portion of the payment is from state funds and what portion is from federal funds.

† Less than 0.1 percent of these funds are provided by the California Department of Aging.

‡ CalOptima received a small amount of member funds (less than $7,000).

In accordance with the contract between CalOptima and DHCS, DHCS makes monthly payments to CalOptima on behalf of each Medi‑Cal member. DHCS makes these payments in amounts that are based on per‑member rates for the provision of covered services (rates). DHCS can also establish an upper and lower limit (rate range) for the rates. For example, the rate range for DHCS’s monthly payments to CalOptima for an adult member from January through December 2022 was from $246 to $262 approximately. According to the CRDD assistant chief, DHCS typically sets base rates for managed care plans at or near the lower limit of the rate range. If plans participate in the process that we describe below, however, he said that DHCS has paid up to the upper limit of the range. Then, according to CalOptima’s chief operating officer, CalOptima contracts with providers of Medi‑Cal services at negotiated rates to provide services to its members.

To enable managed care plans to compensate providers of Medi‑Cal health care services and to support the Medi‑Cal program, state law allows DHCS to operate the Voluntary Rate Range Program. Under this program, DHCS may increase the rates paid to managed care plans like CalOptima from the lower limit of the rate range to the upper limit of the rate range. Through the program, DHCS may accept what is known as an intergovernmental transfer (IGT). DHCS then obtains federal matching funds to the full extent permitted under federal law. This report refers to the process DHCS administers under its Voluntary Rate Range Program as the IGT process.

The IGT process involves a partnership between managed care plans and participating government entities (funding partners). To begin this process, DHCS requests proposals from managed care plans to participate in the IGT process, and it requires the plans to contact potential funding partners to determine their interest in and desired level of participation in the IGT process. Through the IGT process, which Figure 1 depicts, the interested funding partners voluntarily transfer funds to DHCS (IGT contribution). State law specifies that DHCS is generally required to assess an additional 20 percent fee on the value of a funding partner’s IGT contribution to reimburse DHCS for administering the IGT process and for support of the Medi‑Cal program.

Figure 1

The IGT Process Provides Increased Funding to Pay for Medi‑Cal Costs

Source: State law, IGT contracts and agreements, and DHCS internal correspondence.

* Assumes a 1:1 federal match and a managed care plan retention rate of 2 percent.

Figure 1 description:

Figure 1 is a diagram that illustrates the IGT funding process. The figure shows four steps in the process. In the first step, funding partners voluntarily transfer funds plus, if required, a 20 percent administrative fee to DHCS. In the second step, DHCS obtains federal matching funds from CMS. In step 3, DHCS pays the IGT funds, which include both the funding partners' original contribution and federal matching funds, to the managed care plan as part of its rates. Finally, in step 4, the managed care plan pays the IGT funds to providers designated by the funding partners. The plan’s agreements with the funding partners may allow it to retain a portion of the funds. The figure also lists the amounts paid and received by each party for a $100 contribution to the IGT process assuming a 1 to 1 federal match and a managed care plan retention rate of 2 percent. In this example, the funding partners pay in a contribution of $100, and an administrative fee of $20. CMS contributes $100 in federal matching funds, which results in a total of $220 paid in. From this $220, the funding partners receive $198, DHCS receives $20, and the managed care plan retains $2. The source for the information in Figure 1 is state law, IGT contracts and agreements, and DHCS internal correspondence.

DHCS then obtains federal matching funds based on the amount of the funding partners’ IGT contributions, and it pays the total amount of the IGT contributions and federal matching funds (IGT funds) to managed care plans. It does so by increasing the rates within the established rate range and paying the IGT funds as part of the rates it pays to managed care plans for Medi‑Cal services. The IGT process thus results in more revenue available to pay for the costs of Medi‑Cal services. The funding partners that participate in the IGT process may receive IGT payments for services they provide themselves, or they may designate a provider to receive the IGT payments.

CalOptima’s board directed it to implement the IGT process in 2011. At that time, CalOptima anticipated expanding its Medi‑Cal membership as a result of early implementation of components of the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Affordable Care Act). Under the Affordable Care Act, eligibility for Medi‑Cal expanded to include nearly all non‑elderly adults with incomes at or below 133 percent of the federal poverty level. CalOptima identified that the IGT process could generate matching funds needed to leverage federal funding for members added through this expansion (expansion members), and its board approved entering into an agreement with the University of California Irvine Medical Center as its initial funding partner in the IGT process.

CalOptima’s IGT Funding Partners

as of December 2022

- University of California Irvine Medical Center

- First 5 Orange County, Children and Families Commission

- County of Orange Health Care Agency

- City of Orange Fire Department

- City of Newport Beach Fire Department

Source: CalOptima board meeting agenda materials, CalOptima correspondence, funding partners’ websites, and interviews with CalOptima staff.

Since then, CalOptima has continued to use the IGT process, and additional funding partners have elected to participate in the process. State law allows a broad range of government entities to elect to participate in the IGT process and transfer funds in support of Medi‑Cal. The text box shows CalOptima’s five current funding partners.

ISSUES

CalOptima Has Accumulated Surplus Funds It Should Have Used to Improve Services

Key Points

- CalOptima accumulated surplus funds of $675 million in excess of its designated reserves instead of spending those surplus funds as county ordinance specifies.

- CalOptima’s reserve policy was consistent with recommended practices and was similar to the policies of other managed care plans we reviewed, but its surplus funds exceeded the reserve amount set in policy by a greater degree than we observed at similar entities.

As of June 2022, CalOptima’s Surplus Funds Exceeded the Amount of Its Designated Reserves by $675 Million

The Orange County ordinance that created CalOptima requires it to implement a financial plan that includes the creation of a prudent reserve. The reserve policy that CalOptima’s board adopted specifies that it maintain board‑designated reserves of no less than 1.4 months and no more than 2.0 months of certain revenues, which is similar to financial practices recommended by the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA). CalOptima’s audited financial statements describe the funds it has set aside for these reserves as its board‑designated assets. Throughout this report, we present the amount of these funds as CalOptima’s reserves, as CalOptima has stated in various public and board documents. As of June 30, 2022, CalOptima had accumulated more than $1.2 billion of combined reserves and surplus funds—with the surplus being unrestricted funds available for CalOptima’s use that are in excess of its reserves. However, the $675 million in surplus funds should have been used to improve services.

From 2014 to 2022, CalOptima’s reserves increased from $156 million to $570 million, as Figure 2 shows, in part because its membership increased by nearly 50 percent and its revenues increased by a larger proportion—more than 110 percent. However, during the same period, CalOptima’s surplus funds increased by an even larger amount, from $142 million to $675 million. In total, these reserves and surplus funds are equal to 3.5 months of CalOptima’s revenues.

Figure 2

CalOptima’s Surplus Funds Have Significantly Exceeded Its Reserves for Several Years

Source: CalOptima’s audited financial statements for fiscal years 2013–14 through 2021–22.

Note: We obtained the amounts for CalOptima’s reserves from its audited financial statements. To calculate the amount of surplus funds for each year, we subtracted the amount of its reserves from the amount of its unrestricted net position.

Figure 2 description:

Figure 2 is a combination line graph and area chart that shows the amounts of CalOptima’s reserves and surplus fund balances as of June 30 each year from 2014 to 2022. The figure illustrates the significant increase in CalOptima’s surplus funds in recent years. The vertical axis of the chart shows the dollar amount in millions from 0 to $1,500 while the horizontal axis shows the years from 2014 to 2022. A blue line and blue area under the line show the amount of CalOptima’s reserves over this period, while a green line shows the amount of CalOptima’s combined reserves and surplus funds—the amount of funds held in excess of the reserves—over the same time. A yellow area fills the space between the blue and green lines and represents CalOptima’s surplus funds. The figure shows that beginning in 2014, CalOptima had $156 million in reserves, and $298 million in combined reserves and surplus funds. The yellow area between the two lines on the graph shows that CalOptima had about $142 million in surplus funds in 2014. The figure then shows that in 2015, CalOptima’s reserves increased sharply to about $460 million, and that CalOptima had only a small amount of surplus funds—about $30 million to $40 million—for the next few years. Specifically, the figure shows that CalOptima had about $460 million in reserves and $490 million in combined reserves and surplus funds in 2015, $476 million in reserves and $518 million in combined reserves and surplus funds in 2016, and $535 million in reserves and $564 million in combined reserves and surplus funds in 2017. Then from 2018 to 2022, the green line representing CalOptima’s combined reserves and surplus funds makes a series of steady increases, with the sharpest increase between 2020 and 2021. During the same period the blue line representing CalOptima’s reserves stays about the same. Specifically, CalOptima had about $538 million in reserves and $625 million in combined reserves and surplus funds in 2018, $560 million in reserves and $804 million in combined reserves and surplus funds in 2019, $585 million in reserves and $878 million in combined reserves and surplus funds in 2020, $589 million in reserves and $1.16 billion in combined reserves and surplus funds in 2021, and $570 million in reserves and $1.25 billion in combined reserves and surplus funds in 2022, as the figure indicates. As a result of these increases, the yellow area between the lines representing CalOptima’s surplus funds goes from about $30 million in 2017 to $675 million in 2022. The source for the amounts shown in Figure 2 is CalOptima’s audited financial statements for fiscal years 2013–14 through 2021–22. A note explains that we obtained the amounts for CalOptima’s reserves from its audited financial statements, and to calculate the amount of surplus funds for each year, we subtracted the amount of its reserves from the amount of its unrestricted net position.

State law requires CalOptima and most managed care plans to maintain a minimum level of financial equity, and contracts between DHCS and managed care plans to provide Medi‑Cal services also require the managed care plans to maintain that amount of financial equity. However, this amount may not be enough to meet the plans’ needs in the event of unforeseen circumstances. In CalOptima’s case, the amount of financial equity required was equal to less than 10 days of revenues as of June 2022. By contrast, the GFOA recommends that governments maintain reserves equal to no less than two months of their annual revenue or expenditures. Thus, CalOptima’s decision to establish a policy with a reserve level higher than the minimum amount of financial equity that state law and its contract with DHCS require was a prudent choice.

According to CalOptima’s chief financial officer (CFO)—who began her current tenure at CalOptima in 2014 and her current position in 2019—the board‑designated reserve level is sufficient to meet regulatory requirements and to allow CalOptima to meet its obligations in the event of unexpected circumstances. Therefore, CalOptima does not appear to need a larger reserve.

Although CalOptima has maintained reserves that satisfy the requirements in county ordinance, it has not complied with other elements of county ordinance regarding its use of surplus funds that are in excess of its reserve. The Orange County ordinance that requires CalOptima to implement a financial plan including a prudent reserve also requires the financial plan to provide that if additional surplus funds accrue, those additional funds shall be used to expand access, improve benefits, or augment provider reimbursement, or for a combination of those purposes. CalOptima’s board adopted a policy for reserve funds that took effect in 1996, and in 2012 the reserve level was set at no less than 1.4 months and not more than 2.0 months of certain CalOptima revenues; this upper range is consistent with the GFOA’s recommendation for government reserves.

CalOptima’s board established this reserve level to comply with state requirements, maintain CalOptima’s health care delivery system during short‑term crises, and protect CalOptima’s long‑term financial viability. The policy allows CalOptima staff to use the reserves to provide payments to providers and vendors in the event of a delay in CalOptima’s receipt of revenues from the State. However, this policy does not specify, as the county ordinance requires, what CalOptima will do with any surplus funds it accumulates that are not part of its reserve.

By June 2022, CalOptima had combined reserves and surplus funds equivalent to 3.5 months of revenues, considerably more than the reserves its policy specifies, as Figure 3 shows. These surplus funds represent $740 per member that CalOptima should have used as specified in county ordinance for purposes such as expanding access. CalOptima could have done so, for example, by incentivizing providers to serve additional CalOptima members. The most significant increases in surplus funds have occurred since June 2017, when there was less than $29 million in surplus funds. Between then and June 2022, this surplus increased to $675 million.

Figure 3

Since 2018 CalOptima’s Combined Reserves and Surplus Funds at Fiscal Year‑End Have Exceeded the Maximum Level Established in Its Policy

Source: CalOptima’s audited financial statements for fiscal years 2013–14 through 2021–22, its reserve policy, and interviews with its controller.

Note: According to its controller, CalOptima keeps its reserve funds in specified investment accounts, and it has not transferred additional funds into those accounts since 2017. However, because CalOptima’s revenue increases and decreases over time, the number of months of revenue the reserve funds represent will change over time if CalOptima takes no action.

* Although CalOptima had surplus funds sufficient to meet the reserve requirement in fiscal year 2013–14, it had not yet transferred the funds into accounts for that purpose.

Figure 3 description:

Figure 3 is a stacked column chart that represents the amounts of CalOptima’s reserves and surplus funds from 2014 to 2022 as an equivalent number of months of revenue. The vertical axis of the chart shows the months of revenue as of June 30 each year, which ranges from 0 to 3.5 months, while the horizontal axis shows the years from 2014 to 2022. Dashed horizontal lines across the chart at 1.4 months and 2.0 months, with a shaded area between them, indicate CalOptima’s range of reserves. A text box on the chart with an arrow pointing to this region explains that CalOptima’s reserve policy specifies that CalOptima maintain reserve funds of no less than 1.4 and no more than 2.0 months of certain annual revenue. For each year from 2014 to 2022 there are two stacked columns; a blue column on the bottom representing CalOptima’s reserves for the given year, and a yellow column on top of the blue column representing CalOptima’s surplus funds. The figure shows that at fiscal year-end in 2014, CalOptima had less than one month of reserves, which is below the range in the policy, but that its combined reserves and surplus funds equaled about 1.8 months of revenues, which is within the range. The blue columns on the figure show that CalOptima’s reserves doubled in 2015, and that from 2015 to 2017 CalOptima’s reserves remained at 1.8 months of revenue. The yellow columns stacked on top of the blue columns show that the combined total of the reserves and surplus funds were about 1.9 to 2.0 months of revenue during those three years. This indicates that both CalOptima’s reserves, and its combined reserves and surplus funds, were within the range specified by its policy during this time. In 2018, the figure shows that CalOptima had 1.9 months of reserves, which is within the policy range, but its combined reserves and surplus funds were equal to 2.2 months of revenue, which exceeds the maximum specified by the policy. During the next four years CalOptima’s months of reserves decreased slightly, though staying within the range of the policy, while its combined reserves and surplus funds increased considerably to almost double the policy range. Specifically, in 2019 CalOptima had 1.9 months of reserves, and 2.8 months of combined reserves and surplus funds, a considerable increase from 2018. In 2020 reserves stood at 1.8 months, while combined reserves and surplus funds were 2.7 months, a slight decrease from the prior year. However, while CalOptima’s months of reserves decreased slightly again in 2021 to 1.7 months, its combined reserves and surplus funds jumped sharply to 3.4 months. Finally, the figure shows that in 2022 CalOptima had 1.6 months of reserves, but 3.5 months of combined reserves and surplus funds, significantly more than the 2.0 month maximum its policy specifies. The source of the information in Figure 3 is CalOptima’s audited financial statements, its reserve policy, and its controller. A note indicates that according to its controller, CalOptima keeps its reserve funds in specified investment accounts, and it has not made any additional investments into its reserve accounts since 2017. However, because CalOptima’s revenue increases and decreases over time, the number of months of revenue the reserve funds represent will change over time if CalOptima takes no action.

CalOptima’s reserves and surplus funds increased for several reasons. From June 2014 through June 2017, some of the increase was because of the Medi‑Cal expansion program that started on January 1, 2014, in response to the Affordable Care Act. CalOptima’s CFO explained that during 2014 and 2015, CalOptima’s reserves increased due to expansion members. She stated that DHCS set the rates it paid managed care plans for expansion members using assumptions based on other types of members such as seniors and persons with disabilities, and that after implementing the program, the expansion population turned out to be more comparable to the Medi‑Cal adult population. Essentially, DHCS overpaid managed care plans for the cost of caring for the expansion members. The CFO said that the payments for this population resulted in CalOptima's having a higher‑than‑usual margin of revenue over expenditures—or profit—for expansion members until DHCS reduced the rates for expansion members beginning in 2015.In 2018 DHCS took steps to recoup excess payments that managed care plans received for covering newly eligible expansion members, including $102 million from CalOptima, as we described in our April 2019 report titled Department of Health Care Services: Although Its Oversight of Managed Care Health Plans Is Generally Sufficient, It Needs to Ensure That Their Administrative Expenses Are Reasonable and Necessary, Report 2018‑115. Beginning in fiscal year 2018–19, a variety of other factors contributed to the increases in CalOptima’s surplus funds. Table 2 lists some of the factors identified in CalOptima’s audited financial statements that contributed to the increase in its surplus funds from fiscal years 2018–19 through 2021–22. According to the CFO, some of the significant contributing factors were related to the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Table 2

Several Factors Contributed to the Increase in CalOptima’s Surplus Funds Since 2019

| FISCAL YEAR | CONTRIBUTING FACTORS | INCREASE IN SURPLUS FUNDS (IN MILLIONS) |

|---|---|---|

| 2018–19 | Increased revenues from rate increases, IGT transfers, the California Healthcare, Research and Prevention Tobacco Tax Act of 2016 (Proposition 56); nearly $44 million in investment income; and lower medical expenses. | $157 |

| 2019–20 | Increased revenues from the addition of a new program—the Whole Child Model—and Hospital Directed Payments, IGT transfers, Proposition 56; and $43 million in investment income. | 49 |

| 2020–21 | Increased revenues because of an enrollment increase of 9.4 percent that, according to CalOptima’s CFO, was because of the COVID‑19 pandemic and the suspension of the Medi‑Cal eligibility redetermination and disenrollment process. In addition, the CFO cited lower health care expenses for the newly enrolled members than for other members of the Medi‑Cal population and some delayed or deferred nonurgent services. CalOptima also earned $6 million in investment income. | 280 |

| 2021–22 | Increased revenues from an enrollment increase of 8.6 percent, increased rates for new Medi‑Cal programs, and COVID‑19 testing and treatment services. However, these additional revenues were partially offset by investment losses of $20 million. | 102 |

Source: CalOptima’s audited financial statements for fiscal years 2018–19 through 2021–22 and interviews with its CFO.

The CFO noted that she was not directly familiar with the county ordinance requiring CalOptima to implement a financial plan that provides for the expenditure of surplus funds, and she does not know why CalOptima did not adopt such a policy or include that provision in its board‑designated reserve policy. The CFO did agree that such a formal policy would be helpful. However, she also suggested that she believes that CalOptima’s board did not interpret the county ordinance as requiring CalOptima to have a policy or comprehensive spending plan for using surplus funds. She explained that, instead of a policy or spending plan, CalOptima staff have brought various items to the board for action to spend portions of surplus funds.

The CFO said she believes that when CalOptima does spend surplus funds, it has spent them for the purposes that the county ordinance specifies. However, regardless of whether the surplus funds it has spent were used for the purposes established in the county ordinance, CalOptima has spent only some of those funds and has not established a financial plan for using the remainder to expand access, improve benefits, or augment provider reimbursement, or for a combination of those purposes, as the county ordinance requires.

When CalOptima has identified projects for using surplus funds, it has struggled to spend the funds in a timely manner. For example, CalOptima’s strategic plan for 2020 to 2022 describes committing enhanced funding for health initiatives to benefit members experiencing homelessness. However, as of June 2022—more than three years after CalOptima’s board authorized it to spend $100 million of its surplus funds for those initiatives—CalOptima had allocated approximately $60 million of that total and spent only $34 million. The CFO explained that CalOptima encountered several challenges that slowed down the implementation of new programs and initiatives, challenges that included multiple competing priorities from DHCS and CMS, higher than usual rates of staff turnover and vacancies, and the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Some of the Ways Managed Care Plans Can Use Surplus Funds to Benefit Their Members

- Provide medical services or benefits not normally covered by Medi-Cal, such as community health workers and medically necessary home modifications.

- Pay for medical services when providers are not equipped to bill the responsible party, such as voluntary inpatient detox care that counties are responsible for funding.

- Improve data about members’ medical history by obtaining the medical records for care they received outside of the U.S.

- Make supplemental payments to providers for performing the services associated with certain medical procedure codes that are linked to plans’ quality scores, such as preventive health screenings.

- Offer members incentives, such as gift cards, if they receive health screenings or vaccinations.*

- Pay providers incentives for keeping later hours or opening on additional days, accepting more Medi-Cal patients, or setting aside specific days and times for seeing Medi‑Cal patients.

- Make supplemental payments for certain services only provided by specialists to incentivize those specialists to treat Medi‑Cal patients.

Source: The chief of managed care quality and monitoring at DHCS.

* Subject to DHCS approval.

Regardless of whether these challenges fully explain CalOptima’s struggle to spend the funds it did allocate for this purpose, there were hundreds of millions of dollars in additional surplus funds for which CalOptima did not even identify a purpose. The chief of managed care quality and monitoring at DHCS detailed a number of other ways that managed care plans such as CalOptima can use surplus funds to benefit their members, some of which we present in the text box. At a minimum, CalOptima could have begun the process of spending the surplus funds by allocating them for some of the ideas that the DHCS chief described to us, such as making supplemental payments to providers for certain medical procedures or providing them with incentives for keeping later hours or accepting more Medi‑Cal patients. Devoting funds for these purposes might have addressed CalOptima’s rising surplus more promptly and might have improved access and quality of care for its members.

According to CalOptima’s chief executive officer (CEO), he cannot speak to why CalOptima accumulated surplus funds and did not use them sooner, but in December 2022 CalOptima’s board approved more than $240 million in new allocations. Allocating these funds for a specific purpose is an important step; nevertheless, allocations alone will not reduce CalOptima’s surplus. If CalOptima struggles to spend them, as it has in the past, the surplus may continue to grow. Moreover, according to information the CEO shared with the board in March 2023, CalOptima still had more than $400 million in surplus funds that had not been allocated.

CalOptima’s Reserve Policy Was Similar to Those of Other Managed Care Plans

Other Managed Care Plans We Reviewed

As part of our review, we compared CalOptima’s financial reserves, percent of IGT funds retained, executive management salaries, executive credential requirements, and executive turnover rate to those of the managed care plans listed below. We selected the managed care plans based on their member enrollment, revenues, geographic location, and type. These plans’ reserve policies each specify a certain number of months or days for their reserves, unlike the range of months specified in CalOptima’s policy.

- Central California Alliance for Health

Counties served: Merced, Monterey, and Santa Cruz

Type of plan: Public—county organized health system

Reserve specified by policy: 3 months* - Community Health Group

Counties served: San Diego

Type of plan: Private—not-for-profit

Reserve specified by policy: 4 months† - Inland Empire Health Plan

Counties served: Riverside and San Bernardino

Type of plan: Public—established by local initiative

Reserve specified by policy: 60 days† - Partnership HealthPlan of California

Counties served: 14 Northern California counties

Type of plan: Public—county organized health system

Reserve specified by policy: 60 days†

Source: Managed care plans’ websites, reserve policies, and interviews with managed care plans’ staff.

* Months of reserves based on the amount of certain revenues described as the premium capitation.

† Months of reserves based on monthly operating expenses.

Although CalOptima had accumulated significantly more unspent funds as of June 2022 than its reserve policy allowed, the reserve policy itself appears reasonable. To determine whether CalOptima’s reserve policy was reasonable, we compared it to the reserve policies of four other managed care plans, as the text box describes. We found that CalOptima’s policy was similar to the other plans’ policies and that the purposes of the reserve described in those policies were generally similar. When we spoke with staff at the other plans, the reasons they cited for the level of reserves they established in their policies were generally consistent and included the following considerations:

- The possibility of late Medi‑Cal payments.

- Differences between when they receive Medi‑Cal payments from the State and when they pay their providers.

- Improving their ability to respond to unexpected costs and cash flow issues associated with changes in coverage and enrollment growth in the Medi‑Cal program.

- Other unexpected circumstances.

CalOptima’s CFO described similar reasons for the level of reserves defined in CalOptima’s policy and said that she reviews the policy annually and recommends changes to CalOptima’s board if necessary. As we noted above, although the CFO believes the level of reserves established by the current policy is sufficient, CalOptima has surplus funds that significantly exceed that amount.

Other managed care plans have maintained amounts of funds that more closely align with their reserve policies. Since 2018 CalOptima’s combined reserves and surplus funds have exceeded the range its policy specifies, at times by a considerable amount, as we show in Figure 3. To determine how other plans compare to CalOptima, we compared each plan’s combined reserves and surplus funds—on a per‑member basis for the plan’s two most recently audited fiscal years—to that plan’s reserve policy. Because DHCS pays different rates to different managed care plans, two plans with reserve policies requiring the same number of months of reserves are likely to have different reserve amounts per member. Nevertheless, as Figure 4 shows, CalOptima’s combined reserves and surplus funds per member exceeded its policy by a greater degree than any of the other plans we reviewed.

Figure 4

CalOptima Exceeded Its Designated Reserves to a Greater Extent Than Other Managed Care Plans Exceeded Theirs

Source: Managed care plans’ audited financial statements and reserve policies.

Note: CalOptima and Central California Alliance for Health base their reserves on the amounts of certain revenues, and the three other plans base their reserves on their operating expenses.

* The reserve amount shown for CalOptima is 2.0 months—the maximum amount its policy specifies.

Figure 4 description:

Figure 4 is a clustered column chart that compares the amount of combined reserves and surplus funds per member, to the maximum reserve established in policy per member, for CalOptima and four comparable managed care plans. The vertical axis of the chart shows dollars per member from 0 to $1800, while the horizontal axis shows the fiscal year ending month and year for each plan’s two most recently audited fiscal periods. Across the top of the chart are the names of the five managed care plans, and just below these are the number of months or days of reserves each plan’s policy specifies. From left to right these are: CalOptima, which policy specifies 1.4 to 2.0 months of reserves; Central California Alliance for Health, 3 months; Community Health Group, 4 months; Partnership HealthPlan of California, 60 days; and Inland Empire Health Plan, 60 days. A note indicates that CalOptima and Central California Alliance for Health base their reserves on the amounts of certain revenues, and the three other plans base their reserves on their operating expenses. Also, the reserve amount shown for CalOptima is 2 months—the maximum amount its policy specifies. For each plan there are two pairs of columns; one pair for each fiscal period. For each pair, the blue column shows the maximum reserve established in policy per member, while the teal column shows the amount of combined reserves and surplus funds per member at fiscal year-end. For CalOptima, the figure shows that for the fiscal year ending June 2021, the maximum policy reserve of 2 months of revenue was about $820 per member, while the combined reserves and surplus funds were $1380. For 2022 the maximum policy reserve was $770, while the combined reserves and surplus funds were $1360. For Central California Alliance for Health, at fiscal year ending December 2020, the maximum policy reserve of 3 months of revenue was about $900 per member, while the combined reserves and surplus funds were $1130. At fiscal year ending December 2021, the policy amount was $1020, while the combined reserves and surplus funds were $1400. For Community Health Group, at fiscal year ending December 2020, the maximum policy reserve of 4 months of operating expenses was about $1290 per member, while the combined reserves and surplus funds were $1620. The following year Community Health Group’s maximum policy reserve was $1490 while combined reserves and surplus funds were $1290. For Partnership HealthPlan of California, at fiscal year ending June 2021, the maximum policy reserve of 60 days of operating expenses was about $880, while the combined reserves and surplus funds were $930. The following year Partnership’s maximum policy reserve was $830, while combined reserves and surplus funds were $1040. Finally, at fiscal year ending December 2020, Inland Empire Health Plan’s maximum policy reserve of 60 days of operating expenses was about $710 per member, while its actual combined reserves and surplus funds was just $570. At fiscal year ending December 2021, Inland Empire’s maximum policy reserve was $720, while combined reserves and surplus funds were $680. By clustering the two pairs of blue and teal columns for each plan, the figure demonstrates that CalOptima’s surplus funds per member exceeded its designated reserves to a greater extent than those of other managed care plans did for their two most recently audited fiscal periods. The source of the information in Figure 4 is managed care plans’ audited financial statements and reserve policies.

Recommendations

To ensure that it uses its existing surplus funds for the benefit of its members and to comply with county ordinance, by June 2024 CalOptima should create and implement a detailed plan to spend its surplus funds for expanding access, improving benefits, or augmenting provider reimbursement, or for a combination of these purposes. This plan should be reviewed by its board and approved in a public board meeting.

To comply with county ordinance and to ensure that in the future it does not accumulate surplus funds in excess of its reserve policy, by June 2023 CalOptima should adopt a surplus funds policy or amend its policy for board‑designated reserves to provide that if surplus funds accrue, CalOptima will use those funds to expand access, improve member benefits, or augment provider reimbursement, or for a combination of these purposes. The policy should require that the board review the amount of surplus funds each year when it receives CalOptima’s audited financial statements and direct staff to create an annual spending plan subject to the board’s approval to use those funds within the next 12 months.

CalOptima Retained a Larger Share of IGT Funds Than Other Managed Care Plans

Key Points

- CalOptima’s excessive surplus funds resulted, in part, from IGT funds that CalOptima retained and did not spend for purposes it had identified, such as providing supplemental payments to its Medi‑Cal providers.

- CalOptima historically retained a significantly larger percent of IGT funds than other managed care plans we reviewed, but as of August 2022, it retains only 2 percent of those funds, and it recently reported that its board has allocated substantially all of its remaining IGT funds to various programs.

- CalOptima allocated IGT funds for initiatives addressing the health needs of members experiencing homelessness. However, its efforts to monitor the success of the programs it funded were inconsistent.

CalOptima Retained IGT Funds It Could Have Used to Help Support Health Care Access for Its Members

Some Services That CalOptima’s Funding Partners Provide to Medi-Cal Members With IGT Funds

- Testing for sexually transmitted diseases, as well as counseling and prevention services.

- Diagnosis, treatment, and case management for members with tuberculosis.

- Perinatal substance abuse nursing services.

- Health assessment team for members experiencing homelessness.

- Emergency transportation services provided by city fire departments.

- Senior health outreach and prevention program services.

- Inpatient, outpatient, and emergency medical services.

Source: Letters of interest submitted to DHCS by CalOptima and its funding partners.

As the Introduction established, the purpose of the IGT process is to increase payments to managed care plans, enabling them to more fully compensate providers of Medi‑Cal services and support the Medi‑Cal program. CalOptima’s funding partners use IGT funds to pay for a variety of services, such as those the text box lists. From fiscal years 2012–13 through 2021–22, CalOptima received $815 million in IGT funds, of which it distributed $582 million to its funding partners and retained $233 million. The rates at which CalOptima retains these funds are defined in the contracts CalOptima executes with its funding partners. For example, for the round of IGT funding it received during fiscal years 2020–21 and 2021–22, CalOptima and its funding partners agreed that it would retain 31.35 percent of the IGT payments it received from DHCS.

Until recently, CalOptima retained a substantially higher percentage of IGT funds than the other managed care plans we reviewed. The amount CalOptima retained from IGTs, which it acknowledged was unique among its peers statewide, averaged nearly 30 percent of total IGT funds received from fiscal years 2012–13 through 2021–22. The other plans we reviewed each retained 10 percent or less during a recent period we reviewed, as Figure 5 shows. In fact, one managed care plan we reviewed did not retain any IGT funds. By retaining a smaller percentage of the IGT funds, the other managed care plans were able to pass on a larger portion of the revenue they received to their funding partners for compensating providers and for supporting the Medi‑Cal program, which are the goals of the IGT process.

Figure 5

CalOptima’s IGT Contracts Allowed It to Retain Significantly More Funds Than Comparable Managed Care Plans’ IGT Contracts

Source: Managed care plans’ IGT contracts with funding partners and interviews with staff at the managed care plans.

Figure 5 description:

Figure 5 is a column chart that indicates the percentage of IGT funds that that contracts allowed CalOptima and four comparable managed care plans to retain from funds paid for services provided from July 2019 through December 2020. The figure shows that CalOptima’s contracts allowed it to retain 31 percent of the IGT funds, which is significantly more than any of the other plans included in the figure. Specifically, Partnership HealthPlan of California’s contracts allowed it to retain 10 percent; Community Health Group and Central California for Health each had contracts that allowed them to retain 2 percent; and Inland Empire Health Plan’s contracts allowed it to retain 0 percent of the IGT funds. The source of the percentages presented in Figure 5 is managed care plans’ IGT contracts with funding partners and interviews with staff at the managed care plans.

Beginning in August 2022—shortly after this audit began—CalOptima altered its policy to retain only 2 percent of the IGT funds it receives from DHCS excluding the amount the funding partners initially contributed and, with its funding partners, amended the current IGT funding contracts to reflect this change. During the meeting at which the board approved this policy change, the CEO stated that other plans were retaining less and that he thought reducing CalOptima’s rate of retention was the right thing to do. Nevertheless, a significant portion of CalOptima’s surplus funds were made up of IGT funds it had retained in the past. Although CalOptima has spent more than half of the IGT funds it retained, as of June 2022, it still held $90 million in unused IGT funds, as Figure 6 shows. At that time, these unused IGT funds accounted for 13 percent of CalOptima’s surplus funds. This portion of the surplus resulted from CalOptima's retaining IGT funds at a comparatively high rate and from its failure to spend these funds in a timely manner.

Figure 6

CalOptima Had Not Spent $90 Million of the $233 Million in IGT Funds It Retained Since Fiscal Year 2012–13 (as of June 2022)

Source: CalOptima IGT revenue, disbursement, and expenditure data.

Figure 6 description:

Figure 6 consists of a pair of donut charts which detail the amount of IGT funds CalOptima has disbursed, retained, and spent since fiscal year 2012-13. The larger of the two donut charts details the distribution of the $815 million in total IGT funds that CalOptima has received since fiscal year 2012-13 and shows that it disbursed $582 million of these funds to funding entities, while CalOptima retained $233 million. The second donut chart details CalOptima’s spending by fiscal year of the $233 million of IGT funds it retained. This smaller chart shows that from fiscal years 2012-13 through 2017-18 CalOptima spent $27 million in retained IGT funds; in fiscal year 2018-19 it spent $6 million; in fiscal year 2019-20 CalOptima spent $23 million of IGT funds it retained; in fiscal year 2020-21 it spent $52 million; and finally in fiscal year 2021-22 CalOptima spent $35 million of the $233 million of IGT funds it had retained since fiscal year 2012-13. Together these amounts add up to $143 million. The chart shows that after spending these amounts, as of June 2022 CalOptima still had a balance of $90 million in unspent IGT funds it had retained since fiscal year 2012-13. The source for the amounts in Figure 6 is CalOptima IGT revenue, disbursement, and expenditure data.

Entirety of CalOptima’s Explanation to DHCS of How It Intended to Use Retained IGT Funds:

“CalOptima intends to retain approximately 34 percent of the transaction. These additional retained funds will be used to provide Board-approved programs/initiatives which are Medi‑Cal covered services that benefit Orange County’s Medi‑Cal beneficiaries.“

Source: CalOptima’s IGT funding proposal sent to DHCS in December 2017.

Note: CalOptima used substantially similar language to describe its rationale for retaining similar percentages of IGT funds in five proposals it submitted to DHCS that collectively covered the period of July 2015 through December 2020.

Although CalOptima submitted its proposal to retain IGT funds to DHCS, DHCS’s oversight of the retention rate is limited. CalOptima’s IGT proposals to DHCS have provided very general descriptions of what it intends to do with the retained funds, as demonstrated by the excerpt from the proposal it submitted to DHCS in 2017 shown in the text box. However, under federal regulations DHCS is generally not permitted to direct a managed care plan’s expenditures under its contract with the managed care plan to provide Medi‑Cal services. According to the CRDD assistant chief, for that reason DHCS has not provided any guidance to CalOptima about the percentage or purpose of the IGT funds CalOptima retains.

CalOptima initially made statements suggesting that it had retained IGT funds to spend them on the needs of Medi‑Cal beneficiaries and individuals without insurance. CalOptima proposed to its board in 2011 that the IGT funds it intended to retain could be used to increase coverage of uninsured individuals, to make supplemental payments to its Medi‑Cal providers, or to provide additional financial support to those Medi‑Cal providers whose patient load is geared toward serving Medi‑Cal beneficiaries or the uninsured. Then, in 2012 when CalOptima proposed to its board that it amend a contract with a consultant who was identifying options for using its retained IGT funds, it also stated that it was seeking input from various stakeholders and some of its contracted health networks on potential uses of its retained IGT funds.

Notwithstanding the statements it made to its board regarding its intentions to use these funds, the amount of unspent IGT funds that CalOptima retained grew over the next 10 years. The amount of IGT funds CalOptima received from DHCS increased from approximately $40 million in fiscal year 2012–13 to nearly $129 million in fiscal year 2019–20. Because of CalOptima’s decision to retain a relatively large percentage of IGT funds it received, the amount retained increased as well. However, in each year from fiscal years 2013–14 through 2021–22, it spent less than half of the prior year’s cumulative balance of retained funds.

The reasons CalOptima gave us for not spending these funds more rapidly were not compelling. The CFO stated that in the past three years, CalOptima has increased spending of funds retained from IGTs, but it has encountered challenges that slowed down the implementation of programs to utilize IGT funds. Among the challenges she cited were the COVID‑19 pandemic, other competing priorities, changes in the senior leadership team, and challenges securing its board’s authority to develop programs and spend the IGT funds. Although we acknowledge that such challenges could affect CalOptima’s spending, it maintained a significant and increasing amount of unspent IGT funds for many years. Not only did this fund balance grow for years before the pandemic occurred and during the tenures of various leaders, but CalOptima had approximately a decade to identify that it was not spending the funds it was retaining as fast as it received them and to identify priorities for spending those funds.

Further, CalOptima’s accumulation of unspent IGT funds does not align with the requirements it imposes on its funding partners. Most of CalOptima’s agreements with its funding partners or their designated providers require them to return overpayments if they do not use IGT funds rapidly. Four of the five contracts it made in September 2020 define overpayments as the amount of IGT payments in a given state fiscal year that exceed the providers’ costs of providing services to CalOptima Medi‑Cal members in that fiscal year; those contracts require the funding partners to return the overpayments to CalOptima within 60 days. In contrast, at the end of fiscal year 2021–22, CalOptima itself still had unspent IGT funds it had retained from as long ago as fiscal year 2014–15.

CalOptima did take several steps during 2022 to address the balance of IGT funds it had retained. As we discuss previously, CalOptima’s board has reduced the amount that CalOptima will retain in the next IGT process to only 2 percent. In addition, in December 2022, CalOptima's board allocated the remaining unallocated funds from the most recent IGT process, and its staff presented reports to the board’s finance and audit committee in March 2023, showing that the board had allocated substantially all of its retained IGT funds to various programs. Together, the successful execution of these activities should minimize the balance of CalOptima’s unspent IGT funds. Further, if CalOptima were to implement our recommendation that it adopt or amend its policies to require its board to annually review the amount of its surplus funds, the board would be aware of any future accumulation of unspent IGT funds.

CalOptima Was Inconsistent in Monitoring the Effectiveness of Its Homeless Health Initiatives

CalOptima’s Guiding Principles for

Homeless Health Initiatives

Transparent and Inclusive—CalOptima shall foster transparency in homeless health spending by regularly engaging stakeholders to gather ideas and feedback.

Compliant and Sustainable—CalOptima shall spend funds on allowable uses only, with the strict rule that certain funds must be used for Medi-Cal-covered services for Medi‑Cal members.

Strategic and Integrated—CalOptima shall support programs that honor the unique needs of the homeless population while integrating into the existing delivery system.

Defined and Accountable—CalOptima shall identify measures of success and develop incentives to boost accountability in any new homeless health initiative.

Source: CalOptima board meeting materials and minutes.

CalOptima has allocated a significant portion of retained IGT funds for health care initiatives focused on its members experiencing homelessness. In April 2019, CalOptima’s board designated $100 million for Homeless Health Initiatives (HHI funds) to address the health of those members. Appendix A provides details on 10 such initiatives. In December 2019, the board approved the general guiding principles for using HHI funds that the text box shows. The fourth guiding principle specifically describes establishing measures of success to increase accountability. However, as we detail below, our review of a selection of Homeless Health Initiatives found that CalOptima did not consistently establish such measures for its initiatives.

The requirement to establish measures of success aligns with best practices established by the federal government. For example, the U.S. Government Accountability Office indicates that effective performance management helps improve outcomes in various areas, including health care. It has established a framework for implementing programs and delivering services that includes setting annual and long‑term goals and measuring progress toward those goals. Similarly, the framework for effective program evaluation established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) incorporates indicators and measures to determine whether a program is being implemented as expected and achieving its outcomes. It also notes that outcomes must be precise, documentable, and measurable.

Before it began designating funds for Homeless Health Initiatives, CalOptima established a process for applying for IGT funds (IGT application process). The IGT application process incorporated requirements that aligned with federal guidance and the principles that CalOptima’s board subsequently established for the use of HHI funds. For example, the application form that CalOptima used for projects seeking IGT funds in 2016 indicates that applicants should describe how they will know the project was successful, what type of data will be used to measure success, and approximately how long it will take to determine whether the project has been successful. In addition, the review form for these applications prompts CalOptima’s reviewers to score the applications on categories that include whether the objectives are effective and measurable. According to CalOptima’s executive director for Medi‑Cal and CalAIM (executive director), CalOptima did not use the IGT application process for HHI funds. However, because HHI funds come from CalOptima’s retained IGT funds and because of the board’s guiding principles, we expected to see a similar application process and requirements for HHI funds. Alternately, had CalOptima chosen to use its existing IGT application process, it is likely it would have more consistently identified measures of success and the data necessary to measure progress toward them.

We reviewed seven of the 10 initiatives that CalOptima supported with HHI funds and found that in two instances, CalOptima did have measures of success, and it tracked related data. For example, CalOptima’s contract with one participating health center established a requirement for certain clinical field teams to respond to calls from its homeless response team. The contract includes a requirement for the health center to respond to the calls within a specific amount of time, which is a measurable level of performance or metric of success (metric), and CalOptima collected data that it could use to determine whether clinical field teams achieved that metric.

However, in other instances CalOptima did not follow the principle that its board had created of establishing measures of success. Of the seven initiatives that we reviewed, five did not have defined metrics or did not provide data related to the metric, as Table 3 illustrates. For instance, as of June 2022 CalOptima’s board had allocated $4 million in HHI funds to its Homeless Clinic Access Program to, among other things, compensate clinics for providing preventive and primary health care services at locations including shelters. Although CalOptima collects data on the number of individuals served through this initiative, the executive director explained that CalOptima did not identify a metric because this was a new initiative, and it was difficult for CalOptima to know what the volume of individuals seen would be. Nonetheless, the data CalOptima provided for this initiative included factors for which it could have established a metric, such as the number of hours offered at locations each month. By not establishing a metric for this initiative, CalOptima is not well positioned to evaluate the effectiveness of this program for improving health care for members experiencing homelessness.

Table 3

CalOptima Was Not Consistent in Its Approach to Monitoring Selected Homeless Health Initiatives

| HOMELESS HEALTH INITIATIVE* | DEFINED A METRIC FOR SUCCESS | PROVIDED RELATED DATA |

|---|---|---|

| Recuperative Care | X | X† |

| Clinical Field Teams | ✔ | ✔ |

| Homeless Response Team | X | ✔ |

| Homeless Coordination at Hospitals | X | X |

| Homeless Clinic Access Program | X | ✔ |

| Vaccination Intervention and Member Incentive Strategy | ✔ | ✔ |

| Enhanced Medi‑Cal Services at the Be Well OC Regional Mental Health and Wellness Campus | X | ✔ |

Source: CalOptima’s contracts with its Homeless Health Initiative service providers, Homeless Health Initiative outcome data, CalOptima position descriptions, CalOptima desktop procedures, materials presented to CalOptima’s board, and interviews with CalOptima staff.

* See Appendix A for information on each initiative’s purpose and amount of funds spent as of June 2022.

† We obtained spreadsheets related to this initiative from CalOptima, but according to the executive director, CalOptima did not track data for the initiative. The project manager who provided the spreadsheets explained that they did not show outcomes but were invoices for reimbursement of eligible recuperative care stays. She explained that the spreadsheets allowed CalOptima to only reimburse for stays that were eligible.

CalOptima did even less to establish measures of success and track the data to monitor the impact of other initiatives that we reviewed. For example, CalOptima allocated $2 million in HHI funds annually for five years to its Homeless Coordination at Hospitals initiative, which is intended to help hospitals with the increased costs associated with discharge planning requirements and to help facilitate the coordination of services for homeless individuals with other providers and community partners. As Table 3 shows, CalOptima did not provide data related to this initiative. When we asked for documentation of the outcomes for this initiative, the executive director explained that she was not aware of any outcomes for it. The only outcome for this program that was described to us was provided by the chief operating officer, who said that the outcome was executing contract amendments to include the supplemental funds. Therefore, the only metric that CalOptima established was to distribute funds, and it did not establish an expectation or measure for how those funds would improve the health of its members.

If CalOptima did not expect that there would be improvements to its members’ health as a result of the funds spent for this purpose, it is unclear why it chose to allocate funds to this initiative. Further, if there are outcomes that CalOptima does not measure because it is difficult to do so, CDC best practices suggest that programs can be evaluated through the use of indicators relating to any part of the program, including input, process, and outcome indicators. For example, CalOptima might have measured the number of homeless members for whom hospitals developed discharge plans that included referrals to other agencies. Without metrics to measure and monitor, it is not clear whether this initiative—which represents 10 percent of the total HHI funds—has achieved tangible results aimed at improving health care for members experiencing homelessness.

Causes of Monitoring Inconsistencies

- CalOptima viewed IGT funds as different from HHI funds, and thus for Homeless Health Initiatives it did not use a process that required the identification of a measure of success and relevant data.

- CalOptima wanted to distribute HHI funds in the fastest and most flexible way possible to ensure the greatest impact in the fastest time frame.

- Some initiatives were difficult to implement, and CalOptima focused on making funds available to serve a broad purpose instead of establishing a metric of success for the use of funds that might have discouraged participation in the initiatives.

- CalOptima does not have a policy governing its approach to monitoring the use of HHI funds.

- Different CalOptima leaders were responsible for the various initiatives and did not take the same approach to monitoring them.

Source: CalOptima’s executive director for Medi-Cal and CalAIM.

CalOptima described a number of reasons for its inconsistent monitoring of these initiatives. The executive director was not a part of CalOptima when it developed these initiatives, but she shared her understanding of these reasons, which the text box describes. She also said that although CalOptima does not currently have a policy to do so, she believes that to ensure the responsible and equitable use of HHI funds, CalOptima should consistently establish metrics for success of those initiatives and measure progress towards those metrics.

Housing and Homelessness Incentive Program

A voluntary DHCS incentive program–effective January 2022–intended to support delivery and coordination of health and housing services by doing the following:

- Rewarding managed care plans for developing the necessary capacity and partnerships to connect their members to needed housing services.

- Incentivizing managed care plans to take an active role in reducing and preventing homelessness.

DHCS requires managed care plans that participate in the program to provide information on performance goals and measures, and payment to managed care plans is based, in part, on the achievement of program measures.

Source: DHCS All Plan Letter 22-007.

Without a policy, CalOptima’s decisions to establish monitoring for individual initiatives that used HHI funds were made inconsistently and appear to have been dependent on external requirements or individual staff decisions. For example, in September 2022 CalOptima’s board allocated $40 million of the HHI funds for DHCS’s new Housing and Homelessness Incentive Program, which the text box describes. Payments to managed care plans through this program are based, in part, on specific metrics, such as the number of members experiencing homelessness who received at least one of the managed care plan’s housing‑related services. In January 2023, CalOptima solicited proposals to fund $36.5 million worth of projects in Orange County to mitigate the impact of homelessness, and according to the executive director, in March 2023 the board approved grant agreements for 34 of the 66 proposals received. The executive director also stated that her team is establishing metrics for newer initiatives, such as CalOptima’s Street Medicine initiative, which we describe in Appendix A. Nevertheless, a policy formalizing an appropriate and consistent approach to monitoring the use of HHI funds would help CalOptima ensure that the steps its executive director is taking will continue in the event of a change in leadership from executive turnover, the frequency of which we discuss further in the next section.

Recommendation

To ensure that it can determine whether funds allocated to initiatives intended to improve the health of CalOptima members experiencing homelessness are accomplishing their intended purpose, by June 2023 CalOptima should develop a policy that requires it to do the following when spending those funds or allocating funds for that purpose in the future:

- Establish one or more goals for the use of the funds.

- Establish one or more metrics signifying the successful accomplishment of its goals.

- Measure progress toward the established metric and provide the board with periodic updates on the effectiveness of its use of funds based on those measurements.

CalOptima Did Not Follow Best Practices When Hiring for Some Executive Positions

Key Points

- A former CalOptima board member appears to have violated a state law that prohibits public officials from being financially interested in certain contracts when he entered into an employment contract with CalOptima to serve as its CEO in 2020.

- CalOptima has experienced higher executive turnover than the other managed care plans we reviewed, and it lacks a written policy governing its process for hiring employees. Further, it did not follow best practices or the process it verbally described to us when it hired three of the six executives we reviewed.

CalOptima’s Board Likely Improperly Hired One of Its Own Members to Serve as the Organization’s CEO

A former CalOptima board member appears to have violated state law when he entered into a contract with CalOptima to serve as its interim CEO. Government Code section 1090 generally prohibits state and local officers or employees from being financially interested in any contract made by them in their official capacity or by any boards of which they are members. Courts have found that the purpose of this law is not only to strike at actual impropriety but also the appearance of impropriety. In March 2020, CalOptima’s then‑CEO (CEO 1) announced his pending resignation effective May 2020, and the board subsequently selected one of its members to serve as the interim CEO (CEO 2) and entered into an employment contract with him. Based on the requirements in law and holdings in court cases related to this issue, CEO 2 had a financial interest in this contract, and it does not appear that any exception to the prohibition contained in Government Code section 1090 is applicable. Therefore, it appears that he was prohibited from entering into the employment contract. Despite this fact, CalOptima’s board materials indicate that CalOptima’s chief legal counsel at the time concurred with the board’s action, and the board materials do not contain a record of his raising a legal objection to the contract.

CalOptima’s current legal counsel stated that without a formal investigation, he did not know of any reason why this contract would not be considered a violation of law. However, he also confirmed that CalOptima’s legal counsel at that time no longer works for CalOptima, that none of the current members of CalOptima’s board were regular members of its board at that time, and that the employee involved (CEO 2) no longer works for CalOptima. Nevertheless, when CalOptima’s board chose to hire one of its own members to be the CEO, it created the appearance that the board was acting in the best interest of the individual involved rather than the best interests of the individuals CalOptima serves. Because of our concerns regarding the possible violation of state law, we have referred this matter to the Fair Political Practices Commission.