City of Calexico

Past Overspending and Ongoing Administrative Deficiencies Limit Its Ability to Serve the Public

October 20, 2022

2021-805

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

Our office's audit of the city of Calexico (Calexico)—conducted as part of our high-risk local government agency audit program—concluded that Calexico faces significant risks related to its financial and operational management.

For several years, the city council approved spending despite indications that the city's budgets were based on unreliable financial data. As a result, the city's general fund was in a deficit from fiscal years 2014–15 through 2018–19. Since then, Calexico has maintained a positive fund balance in its general fund. However, its reserves are below the minimum level recommended to mitigate the risks of revenue shortfalls and unanticipated expenditures. Calexico also has inadequate processes for allocating the resources it requires to operate efficiently and identifying how it will generate sufficient revenue. For example, to sustain existing operations over the next four fiscal years, the city projects that it must generate additional revenue of up to $1.3 million annually, yet it lacks a plan for doing so. Calexico also presents its budget in English only—a format that limits the engagement of its residents, the vast majority of whom speak Spanish.

The city has not addressed known administrative deficiencies that prevent the public from benefiting from some funding. Because of its past mismanagement of housing grants, Calexico is prohibited from using more than $780,000 in federal pandemic-related grant funds it was recently awarded. The California Department of Housing and Community Development has repeatedly notified the city of grant mismanagement findings since 2014, but past city management did not disclose to the city council the unresolved status of those findings, obscuring the urgent need to address them.

Respectfully submitted,

MICHAEL S. TILDEN, CPA

Acting California State Auditor

HIGH-RISK ISSUES

| ISSUE | |

|---|---|

| Calexico Has Not Taken Steps To Help Ensure Financial Stability | |

| The city's current financial condition resulted from its past overspending and poor budgeting practices | |

| Calexico has not adopted certain best practices for reducing the risk of financial distress | |

| The city has forgone potential revenue by not regularly updating service fees | |

| The City Lacks a Robust, Accessible Budget Process | |

| Shortsighted budget practices have resulted in additional costs and missed opportunities to provide services | |

| Calexico presents its budget in a format that limits its residents' engagement | |

| Calexico's Unresolved Administrative Deficiencies Have Led to Frozen Grant Funds and Compromised the City's Operations | |

| The public is not benefiting from some pandemic relief funds because of the city's mismanagement of grants | |

| The city's operations have been compromised by a lack of staff prepared to fill key roles | |

| Appendices | |

| Appendix A—Actions HCD Has Directed Calexico to Take to Correct Deficiencies and Comply With Grant Requirements | |

| Appendix B—The State Auditor's Local High-Risk Program | |

| Appendix C—Scope and Methodology | |

| Agency Response | |

| City of Calexico | |

| California State Auditor's Comments on the Response From the City of Calexico | |

Risks the City of Calexico Faces

The city of Calexico (Calexico) faces several significant risks related to its financial and operational management. In June 2021, our office sought and obtained approval from the Joint Legislative Audit Committee (Audit Committee) to conduct an audit of Calexico under our high‑risk local government agency audit program (local high-risk program). This program authorizes the California State Auditor's Office (State Auditor) to identify local government agencies that are at high risk for potential waste, fraud, abuse, or mismanagement or that have major challenges associated with their economy, efficiency, or effectiveness.

We identified that Calexico might be at high risk during our annual evaluation of audited financial statements and unaudited pension‑related information from more than 470 California cities. Table 1 summarizes our analysis of Calexico's risk indicators for fiscal years 2018–19 to 2020–21. We conducted an initial assessment and concluded that the city's circumstances warranted an audit. Following the Audit Committee's approval, we began our audit of the city in March 2022.

Table 1

Calexico Has Exhibited Indications of High Financial Risk

| Fiscal Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Indicator | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 |

| Overall Risk | High | High | High |

| General Fund Reserves | High | High | High |

| Debt Burden | High | High | High |

| Liquidity | High | High | High |

| Revenue Trends | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Pension Obligations | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Pension Funding | Moderate | Moderate | Low |

| Pension Costs | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Future Pension Costs | Moderate | High | High |

| Other Post‑Employment Benefit (OPEB) Obligations | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| OPEB Funding | High | High | High |

Source: Auditor's Local Government High‑Risk Dashboard and analysis of risk indicators based on Calexico's audited financial statements.

See https://auditor.ca.gov/local_high_risk/dashboard‑csa to view the interactive dashboard and learn more about our local high‑risk program.

During the past decade, ill‑advised decisions created a financial crisis that continues to affect Calexico. For several years, the city overspent because its city council approved spending despite indications that the city's budgets were based on unreliable financial data. As a result, the city's general fund was in a deficit from fiscal years 2014–15 through 2018–19. Calexico has taken some steps to improve its financial condition. For example, in June 2016 it loaned $3.5 million from its wastewater fund to its general fund and began reducing expenditures to address the general fund's deficit. It has since paid off the loan, and it has restored and maintained a positive fund balance in its general fund since fiscal year 2019–20. However, the city has not adopted certain policies that could help it avoid making future budget decisions based on inaccurate or incomplete financial data.

Moreover, some policies Calexico has adopted do not fully align with best practices to mitigate the risk of financial distress. For example, the city has a policy to reserve the minimum level of financial resources in its general fund that are generally recommended to mitigate the risks posed by revenue shortfalls and unanticipated expenditures. However, the city's history suggests that this level of reserves may not be sufficient and that it requires further analysis. In addition, the city has forgone potential revenue by not regularly updating the fees it charges for city services, some of which may no longer fully cover the city's cost to provide services.

Calexico's processes for identifying the resources it requires and how it will obtain those resources are not adequate. The city has identified that it must generate additional revenue of up to $1.3 million annually to sustain existing operations. However, it lacks a plan for accomplishing that desired goal through economic development. In fact, it has planned for economic development to occur through the actions of staff it has yet to hire. Further, by not expending resources to maintain and operate its existing facilities, the city has already incurred increased costs and missed opportunities to provide some services to residents.

Calexico also presents its budget in a format that limits its residents' engagement in its budget process. The vast majority of the city's residents speak Spanish at home and, according to census data, more than half of the Spanish‑speaking population speaks English less than very well. Residents have asked that more information be presented in Spanish. However, Calexico presents its key public budgetary documents in English only.

Finally, because of its past mismanagement of housing grants, Calexico is unable to use funding it was awarded that could benefit the public. The city may also have to repay funds that the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) awarded in the past. The city has resolved neither the issues HCD identified nor some other administrative deficiencies that the State Controller's Office (SCO) brought to its attention in 2019. For example, although the SCO identified Calexico's lack of succession planning as a concern, the city has not taken steps to prepare its staff to fill key roles. The city's struggle to do so has led to operational shortcomings, including an inappropriate fee transaction and a need to hire a consultant to assist the finance department with basic accounting tasks. Because of these financial and operational challenges, we determined that the city is at high risk for potential waste, fraud, abuse, or mismanagement and therefore should implement a variety of corrective actions to address its risk factors.

Recommendations

The following are the recommendations we made as a result of our audit. Descriptions of the findings and conclusions that led to these recommendations can be found in the sections of this report.

Legislature

To reduce barriers to civic engagement, the Legislature should consider encouraging or requiring all municipal governments to make key portions of public budgetary documents, such as proposed and adopted budgets, available in a sufficient number of languages to ensure that at least 75 percent of their residents can obtain the documents in their primary languages.

Calexico

To ensure that Calexico's leadership acts promptly to prevent potential deficit spending, by January 2023 the city should adopt a policy that allows the city council to approve its annual budget only if it has audited financial statements for the most recently completed fiscal year, a general ledger that identifies current fund balances, and a current bank reconciliation when city staff present the annual budget. If the city council does not approve the annual budget, the policy should require the city council to suspend nonessential spending until the budget is approved.

To ensure that the city has sufficient unrestricted reserves in its general fund to adequately mitigate risks posed by revenue shortfalls and unanticipated expenditures, by January 2023 it should conduct an analysis to determine whether the minimum level of reserves established in its current policy is sufficient and, if not, it should revise its policy to reflect a more prudent level.

To make clear when it should use general fund reserves and how it will maintain the appropriate general fund reserves level, by January 2023 the city should amend its reserves policy to define conditions warranting such use and to specify how the reserves should be replenished when the balance drops below the level prescribed.

To ensure that it has sufficient liquidity to meet disbursement requirements throughout the year, before adopting its fiscal year 2023–24 budget, the city should forecast its cash needs throughout the fiscal year and maintain a sufficient level of cash assets in the general fund to pay for that fund's expenditures as they occur.

To reduce constraints on its ability to sustain existing service levels and hire new staff, by January 2023 city management should present the city council with options for reducing the city's OPEB liability and actions the city could take to achieve such a reduction by the start of fiscal year 2023–24, including requiring active employees who will be eligible to receive benefits to contribute to the city's OPEB trust fund.

To ensure that city fees and rates are sufficient to pay for the costs of providing services, the city should do the following by January 2023:

- Define in policy how frequently the city should conduct fee and rate studies, clearly identify who is responsible for initiating these studies and making fee adjustments, and identify methods of oversight to ensure that the studies and authorized fee adjustments take place.

- Conduct studies of any fees and rates that require updates per the policy.

To reduce the risk that it will alter fees without city council approval, by January 2023 the city should provide training to staff on how to assess fees.

To ensure that it collects enough revenue to pay for the cost of providing water during a shortage, the city should ensure that its next water rate study considers and, to the extent consistent with legal requirements, incorporates best practices for conservation pricing options, such as tiered rates or seasonal rates and special drought rates.

To improve its ability to allocate limited resources in the most cost‑effective manner and in alignment with its goals for serving the public, the city should do the following before developing its fiscal year 2023–24 budget:

- Develop a detailed plan for generating the revenue it needs to maintain services to the public, including five‑year projections of revenue and expenditures that account for both the expected costs of current operations and planned expansions to operations, such as opening the new recreation center.

- Revise its budget‑change process to require departments to specify the financial and service‑related risks and benefits of approving or denying requests for increasing a department's appropriation of funds or reallocating appropriated funds.

To facilitate its residents' participation in the budget process, the city should establish a policy before developing the fiscal year 2023–24 budget to make key portions of public financial documents, including proposed and adopted budgets, available in a sufficient number of languages to ensure that at least 75 percent of residents can obtain the documents in their primary languages.

To ensure continuity of city operations and services, by April 2023 the city should identify essential tasks, develop a comprehensive succession plan, and provide cross‑training that prepares key staff—especially those in the finance department—to fulfill essential duties in the event of turnover or other absences.

To demonstrate its commitment to employee development and competence, the city should do the following by January 2023:

- Ensure that every city employee has received a written performance evaluation within the past 12 months or, for each probationary employee, that one is scheduled according to the city's policy.

- Establish procedures to hold staff who directly supervise others accountable for providing regular written performance evaluations in accordance with city policy.

To ensure that the city is able to use the grant funds awarded by HCD in a timely manner, by January 2023 the city should submit a corrective action plan to HCD and by April 2023 take all other necessary steps to address the deficiencies that HCD identified.

To ensure that the city has the capacity to address outstanding noncompliance with grant requirements and to manage complex HCD grant programs, by April 2023 the city should implement HCD's direction to use unspent funds to hire a dedicated employee or consultant to address HCD's outstanding findings and manage HCD grant projects.

To ensure that the city council and city residents are aware of issues preventing the use of grant funds, by January 2023 the city should revise its grant management policy to require that staff responsible for managing grants publicly inform the city council of any findings of noncompliance with grant requirements and provide regular updates until the entity that issued the findings has given the city written notice that those findings are fully resolved.

Agency's Proposed Corrective Action

Calexico generally agreed with our recommendations. The city did not submit a corrective action plan as part of its response, but we look forward to receiving the plan by December 19, 2022. At that time, we will assess the specific actions it has undertaken or plans to take to address the conditions that caused us to designate it as high risk.

Introduction

Background

Calexico is located approximately 100 miles east of San Diego on the U.S–Mexico border in southern Imperial County and had nearly 40,000 residents as of 2020. It is a general law city and is therefore subject to the State's general law that governs municipal affairs.Unlike a charter city, which has authority to adopt ordinances and regulations regarding municipal affairs that may be inconsistent with state law that is otherwise applicable to cities, a general law city's ordinances and regulations cannot conflict with the State's general laws. For fiscal year 2021–22, Calexico's budget authorized the equivalent of 166 full‑time city employees to provide services to the public, including law enforcement, fire protection, recreational activities, public facility and infrastructure operation and maintenance, and building safety and inspection services. The city operates under a council‑manager form of government: residents elect officials to a five‑member city council serving staggered four‑year terms; the council members, in turn, appoint a city manager to carry out the council's policies and provide the city with day‑to‑day administrative direction. The city manager, with the assistance of the city's finance director, is also responsible for developing the city's budget. The city council is required to adopt a budget no later than its first regularly scheduled meeting in July each year.

Calexico's current city manager started in the position in July 2022 and as of October 2022, the city is in the process of recruiting a finance director, a position it has filled on an interim basis since February 2022.

Calexico's Financial Resources

Calexico significantly depleted its financial resources during the past decade. The city's annual general fund expenditures exceeded its revenue each year from fiscal years 2012–13 through 2015–16. This overspending exhausted the city's unrestricted general fund reserves balance (general fund reserves). Figure 1 shows Calexico's unrestricted general fund reserves, which decreased by millions of dollars annually from fiscal years 2013–14 through 2015–16. In particular, the general fund reserves were at a deficit from fiscal years 2014–15 through 2018–19. After fiscal year 2015–16, Calexico began rebuilding its general fund reserves and by the end of fiscal year 2020–21, it had a balance of $1.9 million. However, despite this recent positive trend, its general fund reserves remain below the minimum level the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) recommends that governments maintain.

Figure 1

Despite Recent Improvement, Calexico's Fiscal Year 2020–21 General Fund Reserves Were Still Millions Less Than They Were Several Years Earlier

Source: Calexico's audited financial statements for fiscal years 2011–12 through 2020–21.

Figure 1 description:

A bar chart shows the level of Calexico's general fund reserves for the period from fiscal year 2011-12 through fiscal year 2020-21. The fiscal year 2020-21 general fund reserves rebounded to nearly $2 million in fiscal year 2020-21, after having been below zero between fiscal years 2014-15 and 2018-19. At their lowest, the general fund reserves were negative $4 million in 2015-16. The fiscal year 2020-21 general fund reserves were still millions less than they had been at their peak of about $7 million in fiscal year 2012-13.

During recent years, multiple factors—including Calexico's low general fund reserves—have consistently indicated that the city is at high risk of financial distress, as Table 1 shows. Overall, Calexico has limited financial resources and significant liabilities. Specifically, it has a low general fund reserves balance and lacks liquidity—that is, assets that are readily available for spending such as cash and short‑term investments. The city also has not set aside enough funds to fully pay for retirement benefits—pensions and other post‑employment benefits (OPEB)—that its former and current employees have earned. These unfunded liabilities place pressure on the city's limited financial resources.

Calexico's budget for fiscal year 2022–23 includes $162.4 million in citywide expenditures. It includes balanced general fund revenue and expenditures of $18.7 million, respectively. The majority of the city's general fund revenue comes from property and sales taxes, including a temporary voter‑approved sales tax (temporary sales tax). In addition to the general fund expenditures for the various categories that Figure 2 shows, the citywide expenditures include $116.7 million for capital projects, such as improvements to streets and parks, and $6.6 million for payments to satisfy debt obligations—for example, interest payments. The budget also includes $20.4 million for other salaries, benefits, and operations outside the general fund. Those operations include enterprise services, such as the city's airport and its water and wastewater services, which are financed primarily from user fees and charges for the services.

Figure 2

Calexico Budgeted $18.7 Million in General Fund Expenditures for Fiscal Year 2022–23

(in millions)

Source: Calexico's fiscal year 2022–23 budget.

Note: This figure does not show how the city allocates $3.4 million from a temporary sales tax. A portion of this tax is transferred to the general fund to sustain operations and is reflected in the figure above. However, another portion pays for debt service on bonds issued to fund capital projects and is not included in the figure above.

Figure 2 description:

Calexico budgeted $18.7 million in general fund expenditures in fiscal year 2022-23, grouped into the following categories:

- Police – $6.1 million

- Fire – $5.7 million

- Administration and Finance – $2.3 million

- Public Works – $1.3 million

- Community Services – $1.2 million

- Planning and Building – $1.1 million

- Retiree Medical – $900,000

- Housing – $100,000

Calexico Has Not Taken Steps to Help Ensure Financial Stability

The City's Current Financial Condition Resulted From Its Past Overspending and Poor Budgeting Practices

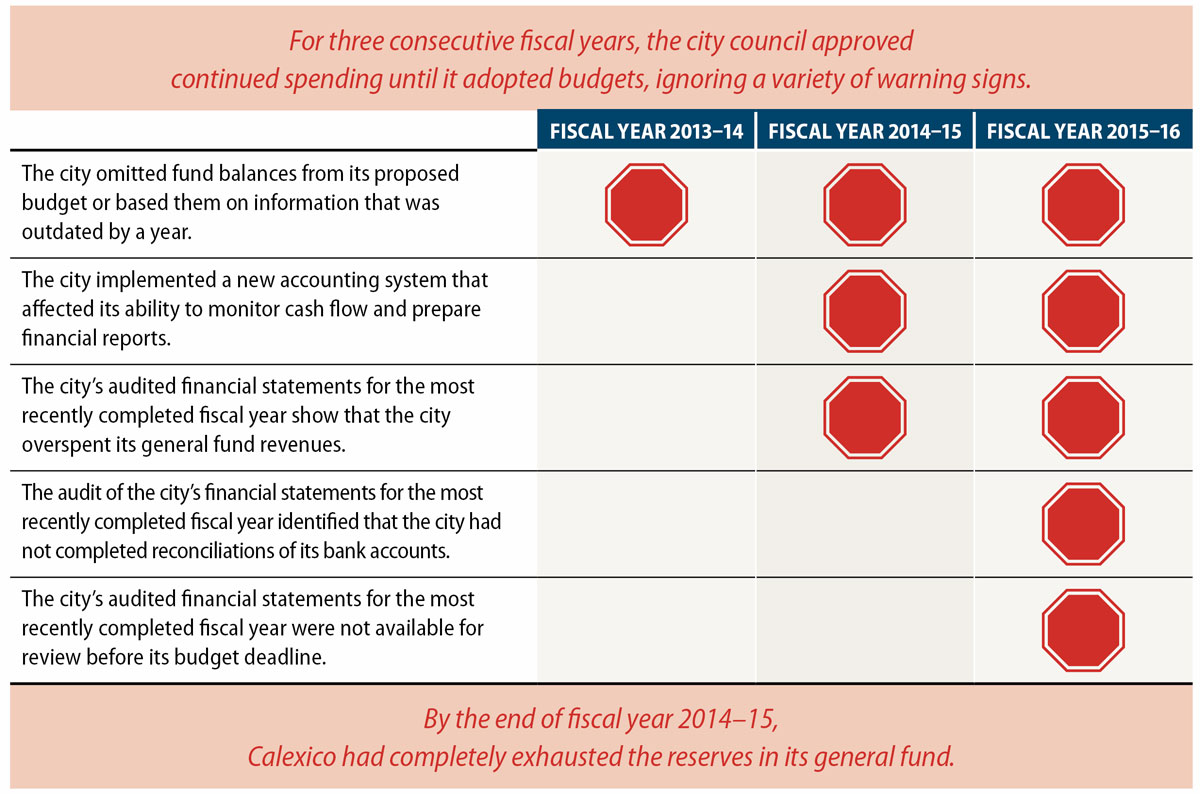

From fiscal years 2012–13 through 2015–16, Calexico engaged in a pattern of spending more from its general fund than it received in revenue, causing a deficit in its general fund and a financial crisis. City leaders could have avoided that deficit—and the resulting financial constraints that still limit the city's public services today—by following prudent financial practices. The GFOA, whose mission is to promote excellence in state and local government financial management, recommends that, when faced with financial crises, one of the first things cities should do is slow their cash outflow and find ways to rebalance their budgets. For example, a city could defer capital spending, start charging fees for services it provided for free in the past, or reduce personnel costs through short‑term hiring freezes and mandatory unpaid furloughs. Such steps would also be prudent for a city that cannot determine whether its spending exceeds its revenue. However, as shown in Figure 3, during some years Calexico's city council ignored warning signs that it did not have accurate information about the city's financial status when making budgetary decisions. In June 2016, when the city council eventually adopted a budget that addressed the city's general fund deficit, it had to make operating cuts and incur debt totaling $3.5 million to do so.

Calexico could have avoided taking on debt by obtaining reliable information and reducing spending instead of passing budgets based on incomplete or outdated information. According to its financial management consultant (financial consultant), the city was in the process of transitioning to a new accounting system at that time, and it accounted for payments in the new system's general ledger but accounted for revenue in the old system's general ledger. Consequently, the city did not have a single source of information from which it could report on its financial condition. Additionally, the financial consultant stated that the city had to find a new banking institution, its bank reconciliations were not current, and it was unable to track its cash position. Although some council members questioned the validity of the budgets during those years, the city council continued to approve budgets with similar spending levels. In one year, the city council simply approved continued spending throughout most of the year without adopting a budget instead of requiring reduced spending until city staff addressed the underlying issues that obscured the council's view of the city's financial position.

Figure 3

Calexico Did Not Heed Warning Signs That Its Budgets Were Based on Questionable Financial Information

Source: SCO's 2019 report on Calexico's internal control system, Calexico's budgets and audited financial statements for the fiscal years listed, and city council meeting minutes.

Figure 3 description:

For three consecutive fiscal years, the city council approved continued spending until it adopted budgets, ignoring a variety of warning signs.

- In fiscal years 2013-14, 2014-15, and 2015-16, the city omitted fund balances from its proposed budget or based them on information that was outdated by a year.

- In fiscal years 2013-14 and 2014-15, the city implemented a new accounting system that affected its ability to monitor cash flow and prepare financial reports.

- In fiscal years 2013-14 and 2014-15, the city's audited financial statements for the most recently completed fiscal year show that the city overspent its general fund revenues.

- In fiscal year 2015-16, the audit of the city's financial statements for the most recently completed fiscal year identified that the city had not completed reconciliations of its bank accounts.

- In fiscal year 2015-16, the city's audited financial statements for the most recently completed fiscal year were not available for review before its budget deadline.

By the end of fiscal year 2014–15, Calexico had completely exhausted the reserves in its general fund.

The city's mismanagement of the budget process culminated in significant overspending in fiscal year 2014–15. In that year's budget, the city budgeted for spending its temporary sales tax revenue for two different purposes. According to the city's financial consultant, the city manager prepared the capital sections of the budget, which committed the temporary sales tax revenue to pay for costs in the capital program, while the finance director prepared the general fund sections of the budget, which committed the same revenue to pay for staff salaries. Because the budget's general fund summary did not include all of the detailed expenditure subtotals, neither city staff nor the city council recognized this budgeting error. Had the budget's general fund summary included those subtotals and added them together, it would have shown, as Figure 4 demonstrates, that actual budgeted expenditures totaled at least $2.4 million more than the erroneous summary of expenditures that the budget presented. This amount also exceeded budgeted revenues by at least $2.4 million. Consequently, by approving the apparently balanced fiscal year 2014–15 budget, the city council actually authorized significant overspending.

Figure 4

The City's Fiscal Year 2014–15 General Fund Budget Summary Did Not Include at Least $2.4 Million of Expenditures Contained in the Budget Details

Source: Calexico's fiscal year 2014–15 budget.

* Total general fund expenditures may be as much as $1.3 million more than we calculated from the budget details. However, we were unable to conclusively determine from the city's budget whether the $1.3 million was included in the budget summary.

Figure 4 description:

Calexico's 2014-15 general fund budget summary presented $17.4 million in total general fund expenditures. However, according to auditor calculations, the budget details included $19.8 million in total general fund expenditures – a difference of $2.4 million.

Ultimately, the city had to take steps to address its deficit, including borrowing funds and cutting spending as the GFOA recommends. Calexico's budget for fiscal years 2015–16 and 2016–17—a two‑year budget that it adopted in June 2016, nearly a year after its budget deadline—included a $3.5 million loan from its wastewater fund to its general fund to provide the general fund with sufficient liquidity. This budget still projected a nearly $4 million deficit, and the city council directed the city manager to reduce staffing if he was unable to balance the budget through other means. The city ultimately did reduce staffing and is still deferring many of its departments' requests for new funding in its fiscal year 2022–23 budget, including nearly all of their requests for new staff. Although the city paid off the loan from its wastewater fund a year earlier than anticipated, during the loan period it incurred interest costs of nearly $200,000 that the city council might have avoided by reducing spending sooner. According to its financial consultant, the city has demonstrated fiscal control through the use of quarterly budget reports that the finance department now presents to the city council. Nevertheless, according to the city's interim finance director, the city has not adopted policies to ensure that it has certain financial documentation, such as audited financial statements for the most recent fiscal year, at the time it makes budgetary decisions.

Calexico Has Not Adopted Certain Best Practices for Reducing the Risk of Financial Distress

Calexico does not currently have sufficient general fund reserves to adequately mitigate the risks posed by revenue shortfalls and unanticipated expenditures. The GFOA recommends that, at a minimum, governments maintain general fund reserves of no less than two months of regular general fund operating revenues or expenditures. However, the GFOA further states that a government's particular situation often may require reserves that significantly exceed this recommended minimum level. In July 2022, Calexico adopted a policy effective for fiscal year 2022–23 to maintain reserves equal to the GFOA minimum recommended level, but it does not anticipate reaching that level until June 2027. Additionally, the policy does not define the specific conditions warranting the reserves' use or describe how the city will replenish the fund if necessary should the balance fall below the level prescribed, which the GFOA also recommends.

Calexico's history suggests that the policy's reserves level may not be sufficient and that it requires further analysis. The city has overspent its budgeted expenditures in a number of the past years. In one fiscal year alone, Calexico overspent its revenue by more than $3.4 million, an amount nearly equal to the $3.5 million it now proposes to hold in reserves. Another reason it may be prudent for Calexico to maintain larger reserves is that it may need to repay certain amounts that it was awarded by a state agency, as we describe later.

The nature of Calexico's existing reserves balance also poses a concern. The GFOA recommends that a city perform ongoing cash forecasting to ensure that it has sufficient liquidity to meet disbursement requirements throughout the year. If at any point a city does not maintain sufficient cash in the general fund to pay for expected costs, it must borrow—resulting in additional expenditures to service the debt—or it may be unable to pay for those costs, which could affect its ability to deliver essential services to residents. However, Calexico's financial statements show that at the end of each fiscal year from 2014–15 through 2020–21, it did not have any liquid assets in its general fund, such as cash or short‑term investments. At the end of fiscal year 2020–21, its general fund reserves consisted almost entirely of amounts that it was owed but had not yet collected. Consequently, the city engaged in short‑term borrowing from its special funds to maintain its operations. For example, the city borrowed nearly $1.2 million from special revenue funds during fiscal year 2020–21.

The city asserted that it lacked cash in its general fund at year-end because it did not cash a check promptly. In May 2021, Imperial County issued Calexico a check for $1.6 million in tax revenue. However, according to the city's interim finance director, the city was unable to cash the check in June 2021, before the end of the fiscal year, because the initial check was lost in the mail. The city's financial consultant further explained that the check was not cashed because of a communication error between Imperial County and the city and that, had the city deposited the check, interfund borrowing would not have been recorded on its audited financial statements and the city would have reported a cash balance in its general fund. However, even if the city had done so, its liquidity level would still have represented a high risk that it would be unable to pay its bills on time without borrowing from other funds.

Further complicating the city's ability to increase its reserves and improve its liquidity is its $39 million OPEB liability. The GFOA recommends that governments prefund OPEB liabilities by creating a qualified trust fund and contributing amounts to the trust fund over time. In most cases, employers can make long‑term investments through such a trust fund to cover these obligations, which should ultimately result in a lower total cost for providing post‑employment benefits. However, Calexico did not set aside annual contributions to offset its unfunded OPEB liability until fiscal year 2020–21. The city began budgeting such amounts in fiscal year 2020–21 but, according to the city's financial consultant, it did not place these amounts into a restricted trust account. Thus, the city's actions did not align with the GFOA's guidance or the Government Accounting Standards Board's requirements for prefunding. As a result, Calexico's financial statements for that year reported that the city's policy was still to fund OPEB costs on a pay‑as‑you‑go basis. In July 2022, after we discussed this issue with the city's interim finance director and its financial consultant, the city adopted a policy to create a trust fund and prefund its OPEB liability. It also budgeted a $242,000 contribution to the qualified trust fund in fiscal year 2022–23, which is consistent with the actuarial projections the city commissioned.

Despite the adoption of this more prudent approach, the city's unfunded OPEB liability remains a significant financial risk. According to the financial indicators used in our dashboard, Calexico's OPEB funding will represent a high risk until the city has enough assets to fund more than 70 percent of its employees' post‑employment benefits—currently expected to occur around 2049, according to the city's actuarial projections. Calexico's recent budgets acknowledge that pension and OPEB obligations are a constraint on its ability to sustain existing service levels or add new staff. However, the city has not taken another important action related to its OPEB liability that could ease this constraint.

The GFOA recommends that governments consider requiring employee contributions to fund OPEB liabilities. Calexico currently does not make OPEB benefits available to employees hired on or after July 1, 2008, with the exception of police officers. However, it does not require employees who will receive these benefits to contribute toward their future costs. In contrast, the city does require employees to contribute toward their pensions and, as Table 1 indicates, pension funding is now a low-risk issue for the city. The city's financial consultant stated that in her experience, OPEB costs are most commonly managed or negotiated by adjusting the retiree benefit level or the retiree contribution, and not by having active employees contribute to OPEB. She also indicated that, generally speaking, it is easier to negotiate cost sharing with employees for a current benefit such as health care or a portable benefit such as a pension than it is for a future retiree health care benefit that might not be transferable if an employee changes employers.

Requiring active employees to contribute toward their OPEB benefits could be more equitable for future employees, and doing so would help ensure that OPEB costs are prefunded. The GFOA states that one of the advantages of prefunding OPEB benefits—in other words, financing them as they are earned—is equity. Specifically, requiring active employees to contribute toward their future OPEB costs makes those who will receive the benefits responsible for financially supporting them, thereby preventing a transfer of the costs into the future that must be paid for by individuals who will not receive the benefits. However, according to the city's interim finance director, the city has not negotiated with active employees to contribute to their future OPEB costs. Therefore, it has not determined how difficult it would be to negotiate cost sharing with employees for these costs.

The City Has Forgone Potential Revenue by Not Regularly Updating Service Fees

Fees and Rates We Examined

- Water and sewer rates: Charges for residential, commercial, manufacturing, and industrial use of water and sewer services.

- Citywide user fees: Fees for city activities and services performed for an individual, business, or group, such as building and planning fees for permits and inspections.

- Airport fees: Fees for airport services including hangar rentals, parking, ramp use, and service calls.

- Emergency medical services fees: Fees charged for ambulance services and medical supplies.

- Development impact fees: Fees that finance the cost of public improvements; public services; and community amenities resulting from new development, such as fire and police facilities.

Source: City ordinances and resolutions, fee schedules, fee studies, and the city's website.

Calexico has not consistently reviewed and updated all of its fees and rates, and at times it has not charged sufficient amounts to cover the costs of certain services it provides. Under state law, a city can impose fees to cover the reasonable cost of providing services. We reviewed the five categories of city fees and rates shown in the text box to determine whether they align with city ordinances and when the city most recently performed a study of the cost of providing the related services. We found that Calexico has not updated some of its fees for many years.

Calexico's outdated fees and rates may not fully cover the cost of certain services. The GFOA recommends that governments adopt policies that define, among other things, how often cost‑of‑service studies (fee and rate studies) will be undertaken. According to several city staff, Calexico lacks such policies, and although significant inflation has occurred that likely increased the city's costs of providing services, many of the city's fees and rates that we examined were last updated many years ago, as Figure 5 shows. Past fee and rate studies identified that certain charges were insufficient to cover the city's costs. For example, when Calexico last performed a citywide user fee study in 2009, it projected that at the rates then current, the general fund was annually subsidizing more than $5.3 million in costs for services provided by various city departments. Although the city did approve temporary adjustments to some building and planning fees for part of fiscal year 2021–22, these adjustments have since expired, and the city has not implemented a permanent update to many of its building and planning fees during the past 13 years. Accordingly, it is likely that the city is subsidizing the cost of providing these services.

The city's funds for specific water, sewer, and airport revenues and expenditures are vulnerable to revenue shortfalls that could affect the general fund if the city does not regularly study and update the associated fees and rates. Calexico's 2009 citywide user fee study projected that the city would subsidize airport services at a cost of approximately $46,000 for that year, most likely through the general fund. The city's public works manager indicated that although the study recommended an increase in airport fees, the city did not adopt the increases at that time. Further, hangar rental fees, which the city describes as a primary revenue source for the airport, are the same as they were 30 years ago.

Figure 5

Despite Significant Inflation, Some Fees and Rates Are More Than a Decade Old

Source: City staff, fee studies, city fee schedules, city ordinances, city council resolutions, and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index.

* The city approved a development impact fee schedule in 2006. At some point after 2006, the city made a modest increase to these fees, but the current city clerk does not know when this increase took place and was not able to locate documentation of the adjustment.

† The city temporarily adjusted certain building and planning fees in 2021 and 2022; however, these adjustments expired in July 2022.

Figure 5 description:

The graph shows that inflation, based on the increase in the consumer price index, has risen significantly over the last 30 years, between 1992 and 2022. However, several of the city's fees and rates were updated more than a decade ago. Airport hangar rates were last updated in 1992. In 2006 the city approved a development impact fee schedule. At some point after 2006, the city made a modest increase to these fees, but the current city clerk does not know when this increase took place and was not able to locate documentation of the adjustment. Similarly, citywide user fees were updated in 2009, though the city temporarily adjusted certain building and planning fees in 2021 and 2022 – adjustments that expired in July 2022. Emergency medical services fee were updated in 2018, and water and sewer rates received their latest update in 2022.

Despite the importance of ensuring that fees are sufficient to pay for the costs of providing services, the interim finance director did not know why the city has not adopted a policy or established timetables for how often staff should conduct fee and rate studies. The public works manager directed us to the fiscal year 2022–23 budget, which includes amounts budgeted for wastewater and water rate studies in fiscal years 2022–23 and 2024–25, respectively, but not for a comprehensive study that would address the other fees we examined. The city manager stated that she is working on a request to hire a contractor to complete a comprehensive user fee and development impact fee study, and she will request an allocation of federal grant funding from the city's American Rescue Plan Act money to fund it. Nevertheless, without a policy describing the circumstances that should trigger updates of user fee studies and fee schedules, there is a risk that the city will not regularly conduct these studies in the future.

In addition to updating its rates more regularly, Calexico should consider possible changes in its supply and use of water when developing its water rates. Although in July 2022 the city was scheduled to impose the last of five annual water rate increases recommended by a 2018 study, this rate structure may not provide sufficient revenue in the future. Before the 2018 study, the city had not conducted a water and sewer rate study since 2006, and the cost of distributing potable water and collecting and treating wastewater had increased significantly since the city modified the rates in 2009.

Calexico obtains its water from a source that is dwindling. The Colorado River is the city's sole source of water, and in August 2022, the federal government announced that Lake Mead—a key reservoir in the Lower Colorado River Basin—will operate in a Level 2 shortage condition in 2023. Although California was not required to make reductions in Colorado River water use as a result of this shortage determination, the Governor and various water districts had already called for residents of certain Southern California cities and counties to reduce water use amid the ongoing drought. According to the consultant who prepared Calexico's water shortage contingency plan (water plan), if Calexico residents reduced water use by 25 percent, which is within the range of the recommended reductions, the city's water fund revenue from residential customers would decrease by an estimated $969,000 per year, or nearly a third of the $3 million it budgets for its water fund reserves.

As required by law, the city adopted a water plan that includes multiple strategies to mitigate water use during shortages, and its water rate structure includes a fixed charge that is intended to cover the city's fixed operational costs and stabilize revenue during a shortage. However, its rate structure does not align with certain best practices for drought response. In particular, Calexico's plan does not employ conservation pricing—such as lawfully enacted tiered, seasonal, or special drought rates—that could help to reduce demand in the event of water supply cuts. The public works manager believes that the city did not consider conservation pricing in its 2018 rate study because it began charging for all of the water that customers actually use instead of allowing them up to 3,000 cubic feet of water each month for the fixed amount they pay, as it had in the past. City staff assumed that changing the rate structure in this way would incentivize ratepayers to use less water. Nevertheless, to ensure that the city has sufficient revenue to supply water in the event of reduced demand, it would be prudent for the city to consider implementing additional drought‑response best practices going forward, such as special drought rates.

Examples of Certain Fees

Adjusted for Inflation

Development impact fee:

Fire facilities fee for a single family residential unit

- Fee in 2006 $689

- Current fee charged $712

- Fee increased by 69% according to construction cost index increase since 2006 $1,164

User fee:

Building permit standard hourly rate

- Fee in 2009 $229

- Current fee charged $229

- Fee increased by 41% according to consumer price index increase since 2009 $323

Source: Analysis of city fee schedules, city ordinances, city council resolutions, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index for urban consumers in the San Diego region, and Engineering News-Record Construction Cost Index.

Further, in several instances, Calexico has not followed the prescribed methodology for increasing certain fees as city ordinances require. For example, according to a city ordinance, development impact fees shall be automatically adjusted annually according to a formula based on a specific construction cost index. However, the city has not updated its fee schedule to reflect these automatic annual adjustments. Similarly, city ordinance requires the finance director to adjust the master user fee schedule, which includes building and planning fees, annually for inflation, but these adjustments have not taken place. The city's interim finance director stated that she was not aware of the city ordinances providing for these annual adjustments.

It was not possible to determine from its audited financial statements the actual amount of revenue Calexico collects from these specific fees because the city combines revenue from various fees in those statements. Accordingly, we were not able to estimate how much additional revenue it could have received had it made annual adjustments to specific fees. However, the development impact fees being charged are nearly 70 percent less than they should be based on changes in the construction cost index, as our example in the text box details.We did not perform a fee study for Calexico and therefore do not opine on whether, if the city had complied with its ordinance requiring annual adjustments for these fees, the increased fees would exceed the city's costs. Past fee studies have indicated that when these fees are insufficient to cover the costs of providing the associated services, the city's general fund must subsidize the difference. Consequently, the city should ensure that it fully recovers the cost of the services it provides and complies with city ordinances related to updating fees.

Please refer to the Recommendations section to find the recommendations that we have made to address these areas of risk to the city.

The City Lacks a Robust, Accessible Budget Process

Shortsighted Budget Practices Have Resulted in Additional Costs and Missed Opportunities to Provide Services

Calexico's budgeting and spending processes are less effective than they could be because they do not include detailed plans and an adequate consideration of future needs. For example, the city has not adequately planned for the costs of operating a recreation facility it plans to build. In 2020 the State awarded Calexico $8.5 million in grant funding to construct, among other things, a new multipurpose gym. According to the city's recreation manager, the city currently uses the Calexico Unified School District's gym, but availability at this space is not guaranteed and the school district has first priority for its use. In theory, having its own gym would allow the city to enhance recreational opportunities for residents. However, according to the recreation manager, there is currently no plan to staff the gym or establish a user fee to support the cost of doing so, and the gym may not be in full operation when it opens unless the recreation department receives additional funding and staffing. The city's fiscal year 2022–23 budget projects that for each of the next five fiscal years, the city's expenditures will be similar to its revenues. However, according to the interim finance director, the projected expenditures do not include the staffing costs of operating the gym. Thus, it is not clear how the city can afford to operate the gym once it has been built.

Calexico's lack of actions to identify and allocate the resources it needs to operate its facilities already affects the public. More than 20 percent of the city's households do not have a broadband Internet subscription—nearly double the statewide average—and the city has the highest unemployment rate in the county. The city has recognized that providing access to broadband Internet, computers, and training in its libraries is critical for education and employment opportunities. It also recently proposed using federal grant funding from the American Rescue Plan Act to provide underserved sectors of the community with expanded broadband access. However, the city already has a technology center providing free Wi‑Fi and Internet‑connected computers, but it does not offer access to these resources because of insufficient staffing. The Carnegie Technology Center (technology center) is a branch of the city library which, according to the library manager, houses 16 of the library department's 36 public computers. According to the library manager, residents want the technology center to be open to the public, yet there is currently no formal plan to do so, and the library's budget is insufficient to hire enough people to staff it.

Calexico has recognized that it needs additional revenue in the near future, but it has not identified how it will generate that revenue or who is responsible for implementing a plan of action. The city's 2021 strategic plan established a long‑term objective of increasing city revenues through economic development and other methods to pay the city's debts, improve staffing levels, and maintain city facilities. Nevertheless, the strategic plan does not identify how the city will implement this objective, the priority level it represents, or the party responsible for putting it into action. Calexico's neglect of this issue is significant, as its plans for future fiscal stability are based on this additional revenue. According to its fiscal year 2022–23 budget, the city projects that it will need additional revenue from new economic development of $900,000 to $1.3 million annually in the coming years to sustain existing staffing and services, as Figure 6 shows. However, when we discussed the city's economic development efforts with the city manager, she stated that with the city's current budget and staffing, she does not anticipate the city promoting new development. Yet without this additional revenue, according to the city's five‑year budget projection, its revenues will not keep pace with expected expenditures.

Figure 6

To Sustain Existing Operations, Calexico Will Need to Generate More Than $4.4 Million in New Revenue Over the Next Four Fiscal Years

Source: Calexico's fiscal year 2022–23 budget.

Figure 6 description:

In order to sustain existing operations, the city of Calexico projects it will need to generate new revenue in each of the next four fiscal years. In 2023-24, it projects it must generate about $900,000 in new revenue. In 2024-25, this number rises to a little over $1 million. In fiscal year 2025-26, the city must generate nearly $1.2 million in new revenue, and about $1.3 million in 2026-27.

Although it is relying on revenue from new economic development to balance its future budgets, the city is not moving forward on that development. Since fiscal year 2017–18, each of Calexico's annual budgets has included a goal for its economic development director (development director) and city manager to develop and implement an aggressive strategic campaign to improve the city's economic position. However, the development director position—which the city deems vital to its overall economic recovery—is not an authorized position in the city's fiscal year 2022–23 budget and before that, according to the human resources and risk management director (HR manager), it had been vacant since July 2020. The city also established an advisory body in 2009 to advise the city council on budgetary issues and provide it with a financial plan for the city. The city ordinance establishing the advisory body does not impose qualifications relating to financial knowledge or experience of the members who serve on it. It also does not specify the details of the financial plan the advisory body should develop. This advisory body has met six times since the beginning of 2020 but according to the city clerk, it did not provide a financial plan during that time.

When we discussed the city's economic development plans with current staff, they had no documentation of efforts by the former city manager—who was previously the city's development director—to increase revenue or improve the city's economic position. Further, according to the current city manager, without a development director and other key staff, the city is struggling to promote development projects and business activity that Calexico's economy needs, but it is not possible for the city to hire for these positions because of budgetary limitations.

Not only has the city neglected to identify how it will obtain the resources it needs to maintain current operations, but its inadequate consideration of the risks associated with not maintaining its facilities has also resulted in increased costs. Specifically, according to the city's fire chief, the roof of one of its two fire stations has needed repairs since it was damaged in 2014. He stated that before he became the chief, the fire department submitted a budget request to repair the roof damage. However, when we visited Calexico in May 2022, the roof still had not been repaired. Figure 7 shows the unrepaired roof and subsequent water damage to the interior of the fire station. According to the chief, the city has delayed repairing the roof because of budgetary constraints, and although the current cost to repair or replace the damaged roof tiles is about $27,000, it will cost at least an additional $55,000 to address water damage to the ceiling and drywall caused by the leaking roof.

Although the city has a process for amending its final budget that allows departments to request additional funding or to reallocate approved funding for a different purpose, it does not direct them to identify the financial or service‑related risks of denying the request. Had the city assessed the risk of delaying these repairs when it was first informed of the damage, it might have considered the possibility that subsequent damage would occur if it did not perform the repairs and have chosen to fix the fire station roof promptly.

The city's delay in addressing the damage has resulted in other costs in addition to the repairs. Specifically, in August 2022 the city council approved emergency expenditures of up to $60,000 for a temporary mobile home to house firefighters. According to the city manager, the city took this action because the fire station is currently uninhabitable because of mold that has accumulated for several years. According to the fire chief, the mold is caused by water leaks from the unrepaired roof and, as a result, the city is currently housing firefighters at its other fire station on the east side of town. Because firefighters are now concentrated in one area, the city manager and fire chief expressed concern that residents on the west side of town may experience significant delays to emergency services in some circumstances. The city manager informed us that the city now plans to house firefighters in temporary mobile housing in the parking lot of the damaged fire station for at least two years, and it is in the process of determining if it should demolish or repair the fire station.

Figure 7

Calexico's Delay in Repairing a Fire Station Resulted in Additional Damage

Source: Auditor observation of Calexico's Fire Station Number 2 and interviews with city staff.

Figure 7 description:

In this set of three photos of a fire station, the first two display an unrepaired roof, and the third shows that this lack of repairs led to subsequent water damage to the interior of the building.

Calexico Presents Its Budget in a Format That Limits Its Residents' Engagement

Calexico presents its key financial documents exclusively in English, which creates a language barrier that can limit the civic involvement of many of its residents. Although English is California's official language, the GFOA recommends that cities strive for broader consumption and greater comprehension of the budget document, because the budget identifies the services to be provided and the rationale behind key decisions. Calexico's three most recent annual budgets have included several items that the GFOA recommends to assist readers, such as summaries, a consistent format, and charts and graphs to more clearly illustrate important points. However, Calexico has not addressed one critical characteristic of its population: according to U.S. Census Bureau data for 2020, nearly 96 percent of Calexico residents primarily speak Spanish at home, and more than half of the Spanish‑speaking population speaks English less than very well. Despite these facts, the city currently presents its proposed and adopted budgets in English only.

Calexico has experienced strong civic involvement when it communicates in both English and Spanish. For example, in May 2021, the city distributed a community survey in both English and Spanish to solicit input for the city's strategic plan, and the city noted in the strategic plan that it believed it had an extraordinary response rate from residents. Despite the level of engagement it experienced through this process, Calexico continues to present its budget and other related documents exclusively in English.

Recent comments from residents illustrate that their desire to participate in the budget process is hampered by a language barrier. Figure 8 illustrates some of the concerns about language accessibility that residents have raised during city council meetings. The city manager does not anticipate any issues with establishing a policy to present key financial documents, such as proposed and adopted budgets in the primary language of the city's residents. According to her, doing so may cost more, but she believes it is important that the city be transparent because residents do not currently have access that allows them to participate in city meetings.

Figure 8

Some Calexico Residents Have Raised Concerns About Language Accessibility During City Council Meetings

Source: Auditor transcription of Calexico city council meetings in December 2020 and June 2022.

Figure 8 description:

This figure shows various speech bubbles with comments from Calexico residents who have raised concerns about language accessibility and inclusivity in city council meetings.

- "I would like to support and push for bilingual meetings. It's simple logic; the majority of the city grew up with Spanish as their first language ... How do you expect citizens to exercise their rights if they can't understand?"

- "I'd like to ask why isn't there an agenda in Spanish ... There are people that only speak Spanish … since we are a mostly Spanish-speaking community, you could at least have a separate form for Spanish speakers or people that only understand Spanish. That would be very helpful ... It's more inclusive to the community."

- "So I want to encourage that inclusivity is put at the forefront when these fiscal decisions are made. There's a large Spanish-speaking population here in Calexico … but I think that in order for the Spanish-speaking population to be able to contribute to the important discussions about COVID and about the urgent items that will be discussed at the immediate meetings, it will be essential that our Spanish-speaking population is also able to engage in this discussion."

- "I want to encourage us ... [to] focus on ensuring ... transparency, community engagement and input, and accessibility at the forefront when making these budgetary decisions ... Make it more accessible. Make it in the language that people understand. Make them as accessible as possible because I know it's really hard for folks to engage ..."

Although Calexico has a particularly high percentage of residents who speak a language other than English at home, the Legislature may wish to address language barriers that affect public participation in budget processes among municipal governments throughout the State. As Figure 9 shows, more than 40 percent of the State's residents speak a language other than English at home, a rate that is double the national average. Further, California has the highest percentage of individuals in the country who self‑identify as speaking English less than very well. Municipal governments could be encouraged to present key portions of budgets in both English and other languages. Specifically, if they presented this information in the languages that a majority of their residents speak at home, they could improve public participation. In turn, this participation could improve the public's perception of government performance and the value the public receives from its government.

Figure 9

Many Californians Speak a Language Other Than English at Home

Source: U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey's 2020 five‑year estimates.

Figure 9 description:

A map of the United States highlights California and Calexico. It shows that 22 percent of the United States population speaks a language other than English at home. In California, 44 percent of the population and speaks a language other than English at home and in Calexico this increases to 96 percent of the population.

Please refer to the Recommendations section to find the recommendations that we have made to address these areas of risk to the city.

Calexico's Unresolved Administrative Deficiencies Have Led to Frozen Grant Funds and Compromised the City's Operations

The Public Is Not Benefiting From Some Pandemic Relief Funds Because of the City's Mismanagement of Grants

Because of Calexico's past mismanagement of certain grants, the State has prohibited the city from using funds it was awarded to benefit its residents and small businesses. The California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) awarded the city more than $780,000 in federal grant funds from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) in 2021 and 2022. These funds were awarded to pay for city improvements and assist community members affected by the pandemic, as Figure 10 shows. However, HCD has prohibited Calexico from spending these funds until the city takes action to resolve past findings and concerns related to grants from other programs through which HCD provides federal housing and community development funds to local governments.

Figure 10

Calexico's Mismanagement of Past Grants Has Delayed Federal Funding Recently Awarded for the Public's Benefit

Source: Calexico's program guidelines and grant application forms for the public, city council agenda items, grant agreements with HCD, grant award letters from HCD, and correspondence with HCD.

Figure 10 description:

HCD awarded CARES Act funds for a variety of purposes in order to benefit the public, including:

- $171,000 in May 2021 to pay for low-income residents' essential utilities.

- $341,000 in November 2021 to provide loan assistance to small businesses affected by the pandemic.

- $101,000 in December 2021 to improve public health sanitation infrastructure.

- $170,000 in February 2022 to repair a local fire station.

Funds from these awards will not be available to the city until it resolves HCD's outstanding findings and concerns related to past grants.

HCD has notified the city that its management of grant programs was deficient on multiple occasions over the past several years, but the city has not taken sufficient corrective actions. As Figure 11 details, in November 2014, HCD discussed with Calexico the results of its review of the city's management of funds from the federal Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program. During that review, it identified several deficiencies, such as noneligible expenditures, the city's inability to demonstrate effective loan portfolio management, inaccurate program income reporting, and noncompliance with various federal regulations. In addition to requesting revised program income reports, HCD also directed the city in 2015 to reconstruct its accounting records since at least 2010 to demonstrate whether the city used any grant funds for ineligible costs and, if so, what portion of the funds it must repay.

HCD reminded the city of these deficiencies multiple times over the next few years. In 2018 HCD notified the city that it had received the SCO's report on single audit findings for fiscal years 2015–16 and 2016–17, which included findings related to the federal HOME Investment Partnerships Program (HOME) contract awarded to the city. HCD directed the city to correct deficiencies for both grant programs, but the city has not done so. In April 2022, HCD notified the city that it would not be able to access funds from the CARES Act CDBG program—which is intended to help governments prevent, prepare for, and respond to the spread of COVID‑19—until it had resolved HCD's outstanding findings.

As the timeline in Figure 11 indicates, former city management did not publicly disclose Calexico's inability to access funds. In February 2019, Calexico's assistant city manager (who subsequently served as city manager until April 2022) announced to the city council during a public meeting that Calexico had been awarded HOME funds. However, he did not disclose that use of these funds was contingent on the city's resolution of HCD's findings. In reality, the city was prohibited from spending the funds because it had not resolved HCD's past concerns. As of July 2022, Calexico still had not resolved these concerns, despite paying contractors to help it do so. To address some of HCD's findings, the city obtained services from an accounting firm with which it had an existing contract for forensic accounting services. In August 2018, the accounting firm told the then‑assistant city manager that it had prepared program income reports, which was one of the services related to addressing these findings for which the city paid the firm at least $173,000. However, HCD did not receive the reports until April 2022, when city staff submitted them. The city's director of planning and building services indicated that after the reports were submitted, HCD informed the city that the reports did not resolve the findings.

The city's efforts to address these findings were hampered by its inadequate contract management. In 2019 the SCO reported that Calexico had not adequately overseen its contract with the accounting firm whose services proved inadequate to resolve HCD's findings. The SCO determined that the city had not amended its original contract to reflect changes to the level of services that the city requested for addressing HCD's findings. In addition, the SCO found that the city approved and paid invoices from this contractor that lacked sufficient detail about the services rendered. The city also contracted with a consultant in July 2018 to address the grant deficiencies HCD had identified. The city paid this other consultant approximately $37,000 but according to the city manager, the services the consultant provided also did not resolve any of HCD's findings.

Figure 11

HCD Repeatedly Informed Calexico of Noncompliance Issues That a Former City Manager Did Not Disclose Were Unresolved

Source: Correspondence between HCD and city staff, grant documentation, and video recordings of city council meetings.

Figure 11 description:

2014

- September – HCD reviewed Calexico's CDBG grant program.

- November – Noncompliance Notification Number #1 – HCD discussed the results with city staff.

- December – Noncompliance Notification Number #2 – HCD directed the city in writing to stop all CDBG expenditures.

2015

- June – City Manager Change #1

- August – Noncompliance Notification Number #3 – HCD discussed the results of a follow-up review with city staff.

- September – City Manager Change #2

- December – Noncompliance Notification Number #4 – HCD provided the city a monitoring report describing its findings and requested corrective actions.

2016

- June – City Manager Change #3

2017

- December – City Manager Change #4

2018

- May – Noncompliance Notification Number #5 – HCD identified the SCO's HOME program findings and directed the city to take corrective actions.

- September – Noncompliance Notification Number #6 – HCD identified the SCO's repeat HOME program findings and directed the city to take corrective actions.

2019

- February

- HCD awarded the city HOME funds, under the condition that it resolve all outstanding findings before spending any funds.

- The assistant city manager told the city council that HCD had awarded the city HOME funds and it could offer HOME funds to Calexico residents.

2020

- July – City Manager Change #5 – The assistant city manager became the city manager.

2021

- Early December – Noncompliance Notification Number #7 – HCD informed the city of a variety of conditions it must comply with in order to access CARES Act funds, including hiring a dedicated employee or consultant to resolve outstanding findings.

- Mid-December – The city manager described CARES Act-funded small business loans to the city council. He stated that HCD had issued a formal award notice and that the city was following HCD's requirements, but did not disclose HCD's outstanding findings.

2022

- January – The city manager stated to the city council that HCD had given the city the opportunity to hire a grant coordinator to assist with HCD programs but did not disclose HCD's outstanding findings.

- April

- City Manager Change #6

- Noncompliance Notification Number #8 – HCD advised the interim city manager that the city could not access CARES Act funds until it resolved the outstanding findings.

- July – City Manager Change #7 – The current city manager disclosed to the city council that the city had not resolved outstanding findings and could not access HCD grant funds.

Many of the corrective actions that HCD directed Calexico to take are still outstanding. According to HCD's community development branch chief, the city must create a corrective action plan and reconstruct its accounting records to address HCD's findings. As the text box shows, it will also need to contract with a consultant or dedicate city staff to manage HCD grants. As a result, the city will incur additional costs or investment of staff time before it is able to access the HCD funds. Appendix A summarizes the corrective actions the city needs to take to resolve all of HCD's findings.

Key Steps Calexico Must Take to Access HCD CARES Act Grant Funding

- Submit to HCD and obtain approval of a corrective action plan that describes the city's efforts to address findings HCD communicated to the city in 2015 and 2018.*

- Use unspent grant funds to hire a consultant or dedicated staff to address all outstanding HCD project monitoring findings and manage HCD grants.

- Provide progress updates during weekly meetings between HCD representatives, the city manager, and the consultant or dedicated staff.

Source: Correspondence between HCD and Calexico and interviews with HCD and Calexico staff.

* Appendix A describes the specific actions HCD directed Calexico to take in 2015 and 2018.

Although HCD has demonstrated that it is willing to work with Calexico to address the findings, the city may have a substantial liability associated with the HCD grants to which the original findings relate. In 2015 HCD advised the city that it must repay any noneligible costs that it had charged to the grants and that it must do so using nonfederal funds. Consequently, the current city manager expects that the city will need to repay a portion of the HCD grants from its general fund. Although the city was still working to determine the repayment amount as of September 2022, HCD's review of the CDBG program required corrective actions for program activity dating back to 2010. HCD has indicated that it is willing to restore the city's access to grants once it demonstrates it is taking corrective actions, including beginning to repay these funds.

Calexico did not make progress toward addressing its noncompliance with HCD's grant programs because of a number of factors. The current city manager indicated that previous city staff lacked knowledge and familiarity with these complex grant programs, leading to financial mismanagement and continued failure to address noncompliance. Further, had the city developed a transition plan to address these types of issues when the city experienced turnover, she believes that it could have resolved the noncompliance sooner. However, by not disclosing the ongoing nature of the city's noncompliance to the city council, past city management obscured the need to urgently address HCD's findings so that the public could begin benefiting from grant funds.

The City's Operations Have Been Compromised by a Lack of Staff Prepared to Fill Key Roles

Turnover and vacancies in key leadership positions have exacerbated Calexico's challenges, including its current grant management issues, and they pose an ongoing risk. The GFOA encourages governments to develop strategies for succession planning, placing a high priority on addressing succession planning risks associated with essential positions such as many finance positions. However, when the SCO reviewed the city's system of internal controls for fiscal years 2015–16 and 2016–17, it found that the finance department did not have a succession plan. In January 2019, the SCO recommended to the city that it develop such a plan. Calexico's 2021 strategic plan also identified the city's lack of succession planning as a threat to its ongoing operations and one of the city's highest priorities for action. Nevertheless, according to the city's HR manager, as of May 2022, the city still lacked a succession plan.

Because the city has not planned for succession, the individuals responsible for developing its fiscal year 2022–23 budget did not have training to do so. In early 2022, the city's fire chief and a manager in its finance department (finance manager) temporarily assumed the duties of the vacant city manager and finance director positions, respectively. Those temporary duties included the critical task of overseeing the development and preparation of the city's annual budget. Both also continued performing their regular duties—which, according to the finance manager, in her case already included covering three of the eight authorized positions for the city's finance department. Despite the significance of these responsibilities, both individuals stated that they did not receive written guidance on how to complete the duties of the interim roles they assumed. The fire chief stated that he had only brief conversations with the previous city manager to guide him because the previous city manager quickly exited the position.