Bellflower Unified School District

Has Not Used Its Significant Financial Resources to Fully Address Student Needs

June 23, 2022

2021-108

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

Located in Los Angeles County, the Bellflower Unified School District (Bellflower) has amassed a significant financial reserve—as much as $83 million in fiscal year 2020–21, which far exceeds the minimum amount the State requires. Bellflower consistently has not spent the amount it and its Board of Education (board) had determined was necessary to provide services to its students. Over the last six years, Bellflower could have used some of its available funding to address students’ needs and ensure that it consistently and adequately provided special education services to its students with disabilities.

The imbalance between budgeted and actual spending results, in part, because the district has not clearly communicated its actual spending and available funding to the board, which has reduced the board’s ability to provide effective leadership and oversight. Meanwhile, Bellflower’s students’ math test scores on statewide assessments were below average, and although Bellflower’s graduation rate was higher than the state average, many graduating students were not prepared for college or careers.

Bellflower also has not consistently provided required services and support to students with disabilities. According to decisions the Office of Administrative Hearings issued, Bellflower did not assess students who demonstrated indicators of need or did not provide the services that students’ Individualized Education Programs called for. By not providing these mandated services, the district deprived students of their rights to access equal education.

Finally, the district did not always comply with laws intended to ensure transparency, such as not responding to requests for public records and not consistently complying with open meeting laws. To address these concerns, we made several recommendations to improve Bellflower’s processes.

Respectfully submitted,

MICHAEL S. TILDEN, CPA

Acting California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| CPA | certified public accountant |

| FCMAT | Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team |

| GFOA | Government Finance Officers Association |

| IEP | Individualized Education Program |

| LCAP | local control and accountability plan |

| LCFF | local control funding formula |

Summary

Audit Hightlights…

Our audit of the Bellflower Unified School District highlighted the following:

- » Bellflower has not clearly communicated its financial position, which limits its board’s ability to see that the district has spent less than it budgeted to meet student needs.

- Its financial reserves have grown to $83 million, which is significantly higher than the minimum amount the State requires.

- » The district has not consistently provided mandated services to students with disabilities.

- Administrative Hearings’ decisions on formal complaints show that Bellflower had not assessed students and had not provided the services and updates called for in students’ IEPs.

- » Bellflower did not adequately mitigate disruptions to students’ education during the pandemic.

- The district did not directly communicate with its students’ families about distance learning until late July 2020.

- » The district has not consistently complied with transparency laws.

- Bellflower did not always respond to public records requests as it was required to do, nor did it respond thoroughly and in a timely manner.

- It limited transparency and the public’s opportunity to address the board when it did not disclose required information about its closed sessions.

Results in Brief

Located in Los Angeles County, the Bellflower Unified School District (Bellflower) is overseen by a five‑member Board of Education (board). The board selects a district superintendent and together they set the district’s direction and ensure its accountability to the public. Although Bellflower has had a 15 percent decline in student enrollment since fiscal year 2015–16, its annual general fund revenue has generally remained steady. Nonetheless, Bellflower has consistently spent less than the amounts that its board has approved in its annual budget to meet the needs of its students. Further, the district’s reports to its board and the public have understated its growing financial reserves, which—at $83 million in fiscal year 2020–21—are significantly larger than the minimum amount that the State requires.

Bellflower has not clearly communicated its actual financial position and spending to its board, limiting the board’s ability to provide effective oversight and ensure that the district is meeting the needs of its students. Bellflower spent from 9 percent to 31 percent less than it budgeted in each of the last six fiscal years. In other words, it repeatedly did not spend what it and its board had determined was necessary to provide the services its students required. Bellflower stated that it has used a conservative approach toward budgeting and spending to prepare for worst‑case scenarios. However, we are concerned that its current students may not be receiving services they need under this approach. For example, Bellflower’s students’ scores on the most recent available statewide math tests were below California’s average. Further, the California Department of Education (Education) website indicated that only 39 percent of Bellflower’s graduating students were prepared for college or careers in fiscal year 2018–19.

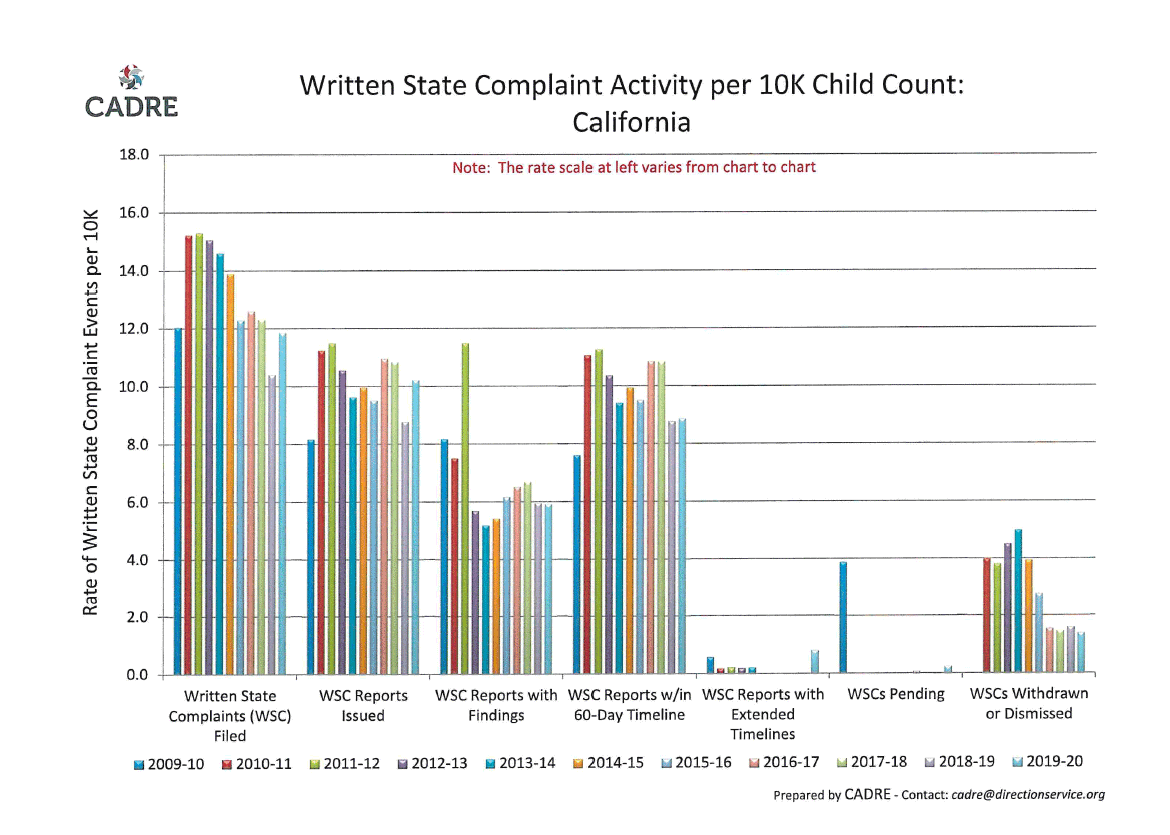

Moreover, Bellflower has not consistently provided required services and support to students with disabilities. An indicator of this inconsistent support is the substantiated complaints that parents have made about Bellflower. When a student’s parents or guardians are unable to resolve issues related to special education with a school district, they can file a complaint that may be heard by the Office of Administrative Hearings (Administrative Hearings) in the Department of General Services. Administrative Hearings decided 15 cases involving complaints with Bellflower in the past five years—a disproportionally high number compared to other school districts that serve more students with disabilities. In 14 of the 15 complaints involving Bellflower, Administrative Hearings ruled that the district did not comply with one or more areas of special education law. Specifically, Administrative Hearings determined that Bellflower did not change services or make accommodations for students who were struggling to access their education, did not include measurable goals in students’ special education programs, or did not perform evaluations to determine whether students required special education services when it had evidence that such evaluations were warranted. Education also found instances of noncompliance when it investigated complaints that Bellflower had violated special education laws.

Bellflower also did not adequately mitigate disruptions to education caused by the COVID‑19 pandemic. After closing its schools for in‑person instruction beginning in March 2020, the district did not directly communicate with its students’ families about distance learning until four months later, in late July 2020. Further, it did not take steps to adequately mitigate learning loss for English learners, foster youth, students who were experiencing homelessness, and students receiving special education services. For example, many parents who are not fluent in English expressed frustration during the school closures that they were unable to help their children learn because the district had not translated their children’s assignments and education platforms.

Finally, Bellflower has not always complied with state laws that require transparency and has missed opportunities to improve its communication with the public. For example, the district did not respond to three of the 10 requests for public records we reviewed that it received in 2021, which is a violation of the California Public Records Act (Public Records Act). With four of the remaining seven requests, the district did not respond within the required time frame, did not adequately fulfill the public records request as required, or both. Bellflower also limited transparency and the public’s opportunity to address the board on closed session meeting topics when it did not comply with requirements to disclose certain information about its closed sessions. Moreover, the district did not always indicate where members of the public could review key planning documents before scheduled public meetings, which it must do according to state law. When the district is not transparent, it limits the public’s ability to participate in its decision making and provide informed feedback on its plans to improve student performance and increase student success.

Agency Comments

Although the district disagreed with some of our conclusions, it agreed to work with its board to discuss our recommendations and formulate action plans for continued improvement.

Recommendations

The following are the recommendations we made as a result of our audit. Descriptions of the findings and conclusions that led to these recommendations can be found in the Audit Results section of this report.

To ensure that it provides its board with an accurate accounting of its available funds, Bellflower should improve its budgeting practices by December 2022. Specifically, the district should evaluate its spending to date every month and more accurately estimate the planned expenditures it includes in its budgets.

To ensure that its board has a clear understanding of the district’s financial position and of the unassigned funds available for programs and services for students, Bellflower should, by August 2022, revise its process for presenting its budget to the board for approval. The revised process should require district staff to present a financial overview that compares year‑to‑date budget amounts to year‑to‑date actual spending amounts.

To increase transparency, the board should, by August 2022, adopt a policy for Bellflower to have its financial auditor present the district’s annual audited financial statements at a board meeting, along with an explanation of the district’s financial health. Further the policy should also require the financial auditor to present the budget‑to‑actual comparison from the district’s audit report and require district staff to explain variances.

To ensure that Bellflower is not underinvesting in its current students, the board should adopt a general fund reserve policy by August 2022 that establishes a healthy but reasonable reserve amount (target reserve) for the district. It should require Bellflower’s staff to use the target reserve when determining funding available for the services the district provides, and staff should ensure that the budget presents any actions necessary to maintain the target reserve.

To ensure that it is providing consistent and adequate services to its students with disabilities, Bellflower should review all its current Individual Education Programs (IEPs) before December 2022. As part of its review, the district should validate that student IEPs comply with legal requirements and that it is providing the services listed on the IEPs. In the future, the district should, as part of its annual review of IEPs, ensure that the IEPs comply with legal requirements and that it is providing the services listed on the IEPs. Bellflower should also take steps to ensure that it has a robust process for identifying students who may have a disability and to appropriately and promptly evaluate those students.

To ensure that it provides consistent and adequate services to all students with disabilities, by October 2022 Bellflower should develop a process to review any instances of noncompliance that either Administrative Hearings or Education identifies, determine the reason for that noncompliance, and establish protocols to address similar problems in the future.

To ensure that Bellflower is prepared in the event of school closures in the future, by October 2022 Bellflower should amend its contingency plan to define roles and responsibilities for district staff, including identifying staff who will be responsible for communicating about school closures and distance learning as well as how those communications will be disseminated. Additionally, Bellflower should include in its contingency plan the district’s method for ensuring that it provides equitable access to distance learning for English learners, foster youth and youth experiencing homelessness, and students receiving special education services.

To ensure that it complies with the Public Records Act, Bellflower should do the following by August 2022:

- Respond appropriately, including redacting confidential information as authorized or required by state law, to the requests we identified in which the district did not provide all the requested documents.

- Require that staff involved in responding to requests receive Public Records Act training.

- Develop formal detailed procedures to ensure that staff track and respond to all requests for records in full compliance with the Public Records Act.

- Establish policy and procedures to retain accurate records and supporting documentation to demonstrate its full compliance with all requirements of the Public Records Act.

To ensure that its board meetings comply with all Ralph M. Brown Act requirements, Bellflower should do the following by August 2022:

- Establish a process to verify that its board meeting agendas include an accurate listing of all closed session topics the board expects to discuss, including required descriptions.

- Offer the opportunity for members of the public to directly address the board before or during consideration of each action item on the agenda and ensure that meeting minutes reflect the comments received.

To ensure compliance with state laws and to improve transparency and communication with the public, Bellflower should do the following by August 2022:

- Before all board meetings, provide the board and the public with the same documentation, such as detailed reports of expenditures and full information on budget revisions, except to the extent such information is confidential and exempt from public disclosure by state law.

- Include its local control and accountability plan and achievement plans as part of the agenda that it posts online for any board meetings in which it intends to discuss the plans.

Introduction

Background

The Bellflower Unified School District (Bellflower) is located in south Los Angeles County and operates 10 elementary schools, two high schools (both grades seven through 12), one continuation high school, one home education academy, and one community day school. Bellflower’s Board of Education (board) consists of five members who are elected by the community to provide leadership and citizen oversight of the district and to ensure that the district is responsive to the values, beliefs, and priorities of the community. The board selects a superintendent to oversee the district’s day‑to‑day operations. Together, the board and superintendent work to set the direction for the district, establish its organizational structure, and ensure its accountability to the public.

Bellflower’s Student Population

Bellflower enrolled 10,700 students in fiscal year 2020–21.

- More than 70 percent, or 7,700 students, were eligible for free or reduced-price meals.

- About 17 percent, or 1,800 students, were designated English language learners.

- About 15 percent, or 1,600 students, had disabilities.

Source: California Department of Education.

Bellflower’s student enrollment for fiscal year 2020–21 was 10,700, a decline of 15 percent from fiscal year 2015–16. The text box provides information about the students Bellflower serves. As Figure 1 shows, state and county enrollments also fell during this period, albeit by smaller percentages. News media sources have reported concerns recently regarding declining enrollment across the State, including declines of more than 15 percent at some school districts, which has spurred the Governor and the Legislature to consider changing how the State funds education to mitigate fiscal impacts of declining enrollment. However, as of this report, no changes to the state funding process have been made.

Figure 1

Bellflower’s Enrollment Has Dropped Each Year Since Fiscal Year 2015–16

Source: Enrollment data from Education.

Figure 1 description:

Figure 1 is a line chart that shows Bellflower’s enrollment has dropped during fiscal years 2015-16 through 2020-21, along with line charts that show similar, but lower declines for enrollment of all California students and Los Angeles County students. Lines indicate the annual percentage change in enrollment. During the period, enrollment declines for all California student ranged from less than 1 percent to 3 percent, for Los Angeles County students from 1 percent to nearly 3 percent, and for Bellflower students from nearly 4 percent to 6 percent. For all three student groups, enrollment declines were highest in fiscal year 2020-21. Source: Enrollment data from Education.

Bellflower’s Revenue and Expenditures

Despite Bellflower’s declining enrollment, its general fund revenue has generally remained steady during the last six fiscal years. As Figure 2 shows, the district’s primary source of funding is the State’s local control funding formula (LCFF), which represents roughly 80 percent of its general fund revenue. Under LCFF, school districts receive base funding that they can use for any local educational purpose, as well as additional amounts (known as supplemental and concentration funds) based on the proportionate numbers of students they serve who are English learners, youth in foster care, and youth from households with low incomes. The district’s total general fund revenue increased from $144 million in fiscal year 2015–16 to $166 million in fiscal year 2020–21. However, this increase was largely the result of the district’s receipt of $17 million in funds related to the COVID‑19 pandemic (pandemic), as we discuss below.

Figure 2

Bellflower Receives Most of Its General Fund Revenue Through LCFF

Source: Bellflower’s audited financial statements and accounting records for fiscal years 2015–16 through 2020–21.

Figure 2 description:

Figure 2 is a stacked column chart that shows Bellflower receives about $118 million to $120 million from LCFF and about $20 million from other funding sources during fiscal years 2015-16 through 2020-21. The graph also shows that in fiscal year 2020-21, Bellflower received about $17 million in pandemic-related funds. Source: Bellflower’s audited financial statements and accounting records for fiscal years 2015-16 through 2020-21.

For fiscal year 2020–21, Bellflower had $142 million in general fund expenditures. Of this amount, $113 million, or 80 percent, was for employee salaries and benefits. Figure 3 shows the categories of expenditures.

Figure 3

Bellflower’s Major General Fund Expenditure Categories Include Employee Salaries and Benefits, Books and Supplies, Special Education, and Operations

Source: Bellflower’s accounting records for fiscal year 2020–21.

Figure 3 description:

Figure 3 is two pie charts that show Bellflower’s major general fund expenditure categories. One pie chart shows that Bellflower spent $133 million (80 percent) on employee salaries and benefits. The other pie chart shows the other 20 percent of Bellflower’s expenditures broken down by category and includes $7.5 million (26 percent) for books and supplies; $5.4 million (19 percent) for special education services; $4.9 million (17 percent) for operations; $3 million (10 percent) for computer or technology related services; $2.8 million (10 percent) for contracted education services; $1.5 million (5 percent) for capital outlay; $1.5 million (5 percent) for transportation services; $1.1 million (4 percent) for administration and other; and $1 million (4 percent) for legal..

In March 2020, the Governor declared an emergency because of the pandemic. The federal government and the California Legislature passed several laws to provide monetary relief to school districts. These laws allocated $67 million in pandemic‑related funding to Bellflower. As we indicate above, it received $17 million in fiscal year 2020–21, of which it spent about $12 million during that year. We discuss the district’s use of these funds in the Audit Results.

Oversight of California’s School Districts

In fiscal year 2013–14, when they implemented the LCFF process to apportion funding to school districts, California lawmakers also shifted responsibility for school district accountability from the State to local stakeholders and board members. The LCFF process requires each school district to develop and annually update a local control and accountability plan (LCAP) that describes the district’s annual goals, services, and expenditures to address state and local priorities. A key requirement each district must follow when it develops its LCAP is gathering input from the public through parent advisory committees as well as parents, students, teachers, principals, administrators, school personnel, and the local community. Essentially, the public provides oversight of the school district by reviewing and giving input on the district’s draft LCAP, while the district is accountable to both the public and its board for carrying out the actions in the LCAP.

In addition to the public, the California Department of Education (Education) and county superintendents each play a role in overseeing school districts. Education collects and reports student data, such as enrollment information; provides accountability through annual updates to the California School Dashboard (dashboard), a tool that reflects how districts are performing in various priority areas defined in law; and conducts compliance monitoring to ensure that districts spend funding in accordance with the law. It is also responsible for investigating and resolving special education complaints it receives related to districts. Consistent with federal law, Education has established two complaint processes: one that is internal through Education and one that functions through an agreement with the Office of Administrative Hearings (Administrative Hearings), an independent office housed within the Department of General Services (General Services). Figure 4 describes these two separate complaint processes.

Figure 4

Education Is Responsible for Two Special Education Complaint Processes

Source: Websites of Education and General Services.

Figure 4 description:

Figure 4 shows two flowcharts that describe how Education is responsible for two special education complaint processes. The first flowchart presents Education’s compliant process, which begins when Education receives a written complaint that a district may have violated special education law or regulation. In the next step, Education screens complaint to ensure that all necessary information is included and, if not, it contacts the complainant to obtain the missing information. Once it receives all the information, it assigns an investigator to the complaint. Education then notifies the complainant and the district that it is investigating the allegation(s). In the next step, Education’s investigator requests the district to respond to the complaint by providing documentation addressing the allegation(s). Then the investigator completes the investigation, including reviewing documents, interviewing relevant parties, and making school site visits if necessary. In the next step, the investigator determines whether the district has violated special education law and completes a written report, which Education mails to the involved parties within 60 days of receiving the complete complaint request. The second flowchart shows the Administrative Hearings’ complaint process, which begins when Administrative Hearings receives a complaint from a family or district that disagree about special education requirements. In the next step, if the parties agree to mediation, the complaint goes to mediation. If mediation is unsuccessful, or if the parties do not agree to mediation, the complaint goes to a due process hearing, where an administrative law judge oversees a trial-like process to determine the outcome of the complaint. After hearing witness statements and seeing accepted documented evidence, the administrative law judge determines whether the district met special education requirements. If a party disagrees with the decision, the party may file an appeal in a state or federal court. Source: Websites of Education and general services.

County superintendents review and approve school districts’ budgets and LCAPs. In Los Angeles County, the superintendent is supported by the staff at the County Office of Education. County superintendents may provide recommended amendments to the LCAPs; however, they have no role in ensuring that school districts implement the approved LCAPs. In addition, county offices are generally responsible for processing their school districts’ expenditures, including determining whether the districts have properly authorized the expenditures and assigned them to the correct fund. For example, a county office determines whether a district has the funds available to cover the total amount of its payroll and has used the correct funding sources based on each employee’s position.

Finally, all California school districts have access to the Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team (FCMAT). FCMAT’s primary mission is to assist K–14 educational agencies in identifying, preventing, and resolving financial, operational, and data management challenges. FCMAT provides services to help avert fiscal crisis but also to promote sound financial practices, create efficient organizational operations, and train and develop high‑level business staff. In most cases, school districts or county offices ask FCMAT for help. In addition, the State’s fiscal year 2018–19 budget authorized additional funding for FCMAT to provide more proactive and preventive services to fiscally distressed school districts. As a result, FCMAT identified situations in which it would engage school districts or county offices, such as when a county office designates a school district as a lack of going concern—a designation that county superintendents can apply to a school district if they believe the school district may be unable to meet its financial obligations for the current or two subsequent fiscal years.

Oversight of Fiscally Independent School Districts

State law allows a school district to bypass county office oversight of most of its expenditures, other than debt service, if the state superintendent of public instruction (state superintendent) grants that district fiscal independence. Fiscally independent districts are authorized to issue their own payments for expenses rather than being dependent on county offices to provide oversight and make payments. Figure 5 shows the process through which a school district may become fiscally independent. FCMAT conducted a survey of county offices in February 2020 and determined that only 10 school districts in California were fiscally independent. This number does not include Bellflower, whose continued status as a fiscally independent school district is a matter of ongoing litigation.

Figure 5

Only the State Superintendent Can Grant Fiscal Independence

Source: State law.

Figure 5 description:

Figure 5 is a flowchart that describes the process for a school district to become fiscally independent. A school district that wishes to become fiscally independent first files a written application with the county superintendent. Once the county superintendent receives the application, state law requires the county superintendent to hire a certified public accountant (CPA) or public accountant to review the district’s accounting controls. Then the CPA or public accountant reports findings and recommendations to the county superintendent, county auditor, and the district applying for fiscal independence. The county superintendent then forwards the district’s application, along with its recommendations, the recommendations of the county auditor, and the CPA or public accountant report on accounting controls to the state superintendent for approval or disapproval. The state superintendent will approve the application if he or she finds that the accounting controls are adequate. If the state superintendent finds the accounting controls are not adequate, he or she will not approve the application. Source: State law.

The state superintendent granted Bellflower fiscal independence effective July 1, 2016. However, in June 2019, the Los Angeles County Office of Education (LA County Office) recommended that the state superintendent revoke Bellflower’s fiscal independence. In its recommendation to the state superintendent, the LA County Office cited its staff’s findings regarding Bellflower’s cash reconciliation and budget assumptions, financial control weaknesses that a third‑party accounting firm had identified, and findings from Bellflower’s annual financial audit report. The state superintendent agreed with the LA County Office’s recommendation and revoked Bellflower’s fiscal independence effective July 1, 2019. However, Bellflower did not agree or comply with the revocation and has continued to operate as a fiscally independent district.

In early June 2020, the LA County Office filed a lawsuit to compel Bellflower to comply with the state superintendent’s revocation of its fiscal independence, a matter that was pending at the time of our audit. In mid‑September 2020, the LA County Office used its authority under state law to designate Bellflower as a lack of going concern. In the written notice to Bellflower, the LA County Office stated that the district had ignored the state superintendent’s revocation order, refused to comply with its directives related to oversight, and denied it access to its fiscal records. Bellflower disagreed with and appealed to Education about the lack of going concern designation in September 2020 and Education denied the district’s appeal. Bellflower filed a lawsuit in early November 2020 asking the court to direct the LA County Office and the state superintendent to desist from claiming that it might be unable to meet its financial obligations in the current fiscal year. The two lawsuits have been consolidated and are currently awaiting trial. Because the revocation process is a pending legal matter, we did not review this as part of the audit.

Audit Results

Bellflower Has Not Presented Accurate Financial Information, Which Hindered Its Board’s Efforts to Address Student Needs

Since fiscal year 2015–16, Bellflower has consistently spent less than it budgeted each year to provide services to its students. The district overstated its expenditures in its budgets and interim financial reports to the board and the public, limiting the ability of both to assess its actual spending. Because Bellflower has spent less than budgeted, its unassigned general fund balance—the amount of money it has available to spend on any activity—has grown considerably, reaching $83 million by the end of fiscal year 2020–21. In fact, Bellflower’s current reserve is 42 percent of its total expenditures—significantly higher than the 3 percent minimum amount that state law requires.

Neither underspending nor a growing fund balance are inherently problematic. However, Bellflower’s failure to clearly communicate its true financial position to its board has limited the board’s ability to provide effective oversight and to ensure that the district is meeting the needs of its students. In fact, Bellflower’s students have struggled on some indicators of academic performance, suggesting that the district should devote at least part of its unassigned general fund to providing additional resources and services. Bellflower’s underspending and growing general fund balance will be difficult for the board to address until the district begins presenting it and the public with clear and accurate information about its financial position.

Through Its Budgets and Financial Reports, Bellflower Has Frequently Misrepresented Its Spending to the Board and the Public

Bellflower’s annual budget represents the collective efforts of the district, its board, and its residents to determine the expenditures necessary to meet the needs of its students given the district’s available funding. Each year, Bellflower develops a budget that identifies its proposed general fund expenditures and estimated revenue for the next fiscal year, together with its estimated actual expenditures and revenue for the current fiscal year. State law requires each school district to present its proposed budget at a public meeting and to identify the expenditures necessary to implement its LCAP. It also requires each school district to obtain its board’s approval of its budget. These processes are intended to ensure that a district’s spending reflects the needs of its students within the constraints of available funding.

Nonetheless, in each year since fiscal year 2015–16, Bellflower has spent less on providing services to its students than the amount its board approved in its annual budget. Figure 6 shows the levels of spending compared to the final approved budget amounts during the past six fiscal years. In the first four of these years, the district spent roughly 9 percent less than it had budgeted to meet the needs of its students, while in fiscal years 2019–20 and 2020–21, that gap rose to 16 percent and 31 percent, respectively. Although Bellflower received $17 million in fiscal year 2020–21 for pandemic relief and spent $12 million of those funds, the district’s underspending of pandemic relief funds was 8 percent of the spending gap during that fiscal year. Moreover, Bellflower consistently underspent in categories that directly impact students, such as books and supplies, and salaries and benefits for teachers. Underspending its budgeted amounts so consistently and in such important categories raises questions about how well the district is meeting its commitments to its students.

Figure 6

Bellflower Spent Less Than It Budgeted During Fiscal Years 2015–16 Through 2020–21

Source: Bellflower’s audited financial statements for fiscal years 2015–16 through 2020–21.

Figure 6 description:

Figure 6 is a line chart that shows Bellflower spent less than it budgeted during fiscal year 2015-16 through 2020-21. One line shows Bellflower’s final budget expenditures, which range from $149 million in fiscal year 2015-16 to $206 million in fiscal year 2020-21. A second line shows Bellflower’s final actual expenditures range from $133 million in fiscal year 2015-16 to $142 million in fiscal year 2020-21. For fiscal years 2019-20 and 2020-21, examples of the amounts budgeted and not spent include $31 million for books and supplies and $28 million for salaries and benefits for teachers. Source: Bellflower’s audited financial statements for fiscal years 2015–16 through 2020–21.

Further, Bellflower provided overstated expenditure information to its board regarding its actual spending need throughout the fiscal year. Each June district staff present—and the board approves—a budget before the next fiscal year starts, which the district refers to as its original budget. Then, during the year, the district adjusts its budgeted revenue and expenditures as more information becomes available, ultimately yielding a budget that it refers to as the final budget. However, despite increasing its planned spending during the fiscal year, the district has rarely spent the increased budgeted amounts, as Figure 7 shows. In fact, over the last six years, Bellflower increased its budgeted expenditures by a total of $128 million, $104 million of which it never spent. This pattern of obtaining budget authority for additional expenditures but never spending most of the increases is misleading.

Figure 7

Although Bellflower Regularly Increased General Fund Budgeted Expenditures During the Fiscal Year, It Often Did Not Spend the Increases or Its Original Budget Amounts

Source: Bellflower’s budgets and audited financial statements for fiscal years 2015–16 through 2020–21.

* Bellflower increased its budget in fiscal year 2020-21 because it received pandemic funding from the Learning Loss Mitigation Fund, Expanded Learning Opportunities Grant, and other sources, but its actual spending remained flat.

Figure 7 description:

Figure 7 is a column and line chart that shows that Bellflower regularly increased general fund budgeted expenditures during the fiscal year, but often did not spend the increases or its original budget amounts. Columns indicate Bellflower’s original budgeted expenditures range from $134 million in fiscal year 2015-16 to $170 million in fiscal year 2020-21. Stacked on that column the chart shows Bellflower’s increased budgeted expenditures, which represent final budget expenditures when taken together with the original budget expenditures and range from $149 million in fiscal year 2015-16 to $206 million in fiscal year 2020-21. A trend line indicates Bellflower’s final actual expenditures range from $133 million during fiscal year 2015-16 to $142 million in fiscal year 2020-21. Consequently, the columns rise above the trend line, while the trend line remains relatively flat. We note on the chart that Bellflower increased its budget in fiscal year 2020-21 because it received pandemic funding from the Learning Loss Mitigation Fund, Expanded Learning Opportunities Grant and other sources, but its actual spending remained flat. Source: Bellflower’s budgets and audited financial statements for fiscal years 2015–16 through 2020–21.

Bellflower has also provided misleading interim financial reports to its board. State law requires that districts submit two interim reports to their governing bodies for approval during the year. These reports compare the status of their actual spending to the budgeted amounts and must include whether the district will be able to meet its financial obligations. All of Bellflower’s interim reports since December 2018—like all of its budgets during that same period—have shown projections of deficit spending and declining fund balances. However, the district’s actual revenue and expenditures are significantly different from its projections. For example, in its fiscal year 2018–19 interim report in December 2018, district staff projected that Bellflower’s deficit spending of $34 million would reduce its unassigned general fund balance to $29 million by the end of fiscal year 2020–21. However, the district’s projections of deficit spending were overly conservative, and actual spending resulted in a surplus that grew the unassigned general fund balance to $83 million. We discuss the district’s general fund balance in more detail below.

Bellflower Has Amassed a Significant Unassigned General Fund Balance

Select Fund Balance Classifications

Restricted: Amounts that are restricted to specific purposes either through externally imposed constraints by creditors, laws, or regulations or through constitutional provisions or enabling legislation. For example, school districts must spend special education funding for support and services for special education students.

Assigned: Amounts in a general fund that are intended to be used for a specific purpose. This intent is expressed by the entity itself or an official to whom the entity has delegated this authority. An entity can change this funding designation if needed.

Unassigned: The general fund balance that has not been assigned to the other classifications above.

Source: Governmental Accounting Standards Board.

A school district’s total general fund balance can contain funding that falls into a number of classifications, some of which we describe in the text box. For instance, a district must use its restricted funds for the specific purposes for which they were intended, such as providing students with food services and special education services. In contrast, a district can use its unassigned funds for any purpose that aligns with its mission and goals. Largely because it has consistently underspent its budgeted amounts, Bellflower has amassed a significant unassigned general fund balance, as Figure 8 shows.The State and the federal government allocated Bellflower $67 million in COVID‑19 relief funding, as indicated in the Introduction. However, the district has not yet received all of this funding and the amounts it has received do not impact its general fund unassigned balance because the funding is restricted and not unassigned. We discuss the status of the district’s spending of these funds later in the report.

Figure 8

Bellflower’s Unassigned General Fund Balance Is Growing and Has Consistently Exceeded Required and Recommended Minimum Levels

Source: Bellflower’s audited financial statements for fiscal years 2015–16 through 2020–21, state law, and the GFOA.

Figure 8 description:

Figure 8 is a line chart that shows Bellflower’s unassigned general fund balance is growing and has consistently exceeded required and recommended minimum levels. One line shows that Bellflower’s unassigned general fund balance grew from $44 million in fiscal year 2015-16 to $83 million in fiscal year 2020-21. One line shows the amount the two months of general fund expenditures that GFOA recommends, which ranges from $22 million in fiscal year 2015-16 to $24 million in fiscal year 2020-21. A third line shows the statutorily required minimum of 3 percent of total expenditures, which ranges from $5 million in fiscal year 2015-16 to $6 million in fiscal year 2020-21. Source: Bellflower’s audited financial statements for fiscal years 2015–16 through 2020–21, state law, and the GFOA.

Since fiscal year 2015–16, the district’s planned expenditures and unassigned general fund balance have increased despite its steady revenue and falling enrollment. One of Bellflower’s justifications for significantly increasing its unassigned general fund balance is its belief that its state funding will be reduced because of its falling enrollment and that it will need its accumulated unassigned funds to maintain student services and to avoid having to cut student programs as it had to do in the past. However, we do not find Bellflower’s justification compelling: although its enrollment has fallen for the last six years, its unassigned general fund balance has increased by $39 million during this same period. Given that the district has not needed to use its general fund balance to compensate for a loss in revenue in recent years, we do not understand why it anticipates needing to do so in the near future. Moreover, the Governor and the Legislature are currently considering changing the State’s approach to funding education to mitigate the fiscal impacts of declining enrollment.

Bellflower’s unassigned general fund balance exceeds both the minimum reserve amount that state law requires and the minimum amount that the Government Finance Officers Association’s (GFOA) best practice recommends. Under state law, school districts of Bellflower’s size must maintain a reserve of at least 3 percent of their total expenditures. However, Bellflower’s current reserve is 42 percent. The GFOA recommends that general purpose government entities maintain a general fund reserve of no less than two months—or 17 percent—of their general fund operating expenditures. Bellflower’s unassigned balance of $83 million represents over seven months of general fund expenditures or more than three times GFOA’s guidance. To inform its fiscal decision making, a district can adopt a reserve fund policy that establishes the ideal amount of funding it will maintain in its reserves, and GFOA recommends establishing a formal policy. However, Bellflower does not have such a policy.

Bellflower’s problematic budgeting processes have hindered the board and the public from easily knowing that the district was accumulating a significant unassigned general fund balance. The original budgets that the district presented and the board approved showed deficit general fund spending—spending in which the district’s planned expenditures exceed its planned revenue, requiring it to spend its reserve funding—in three of the last six years. The final budgets showed planned deficit spending in all six years. However, the district’s expenditures exceeded its revenue only in fiscal year 2018–19, when it spent $3.2 million more than it received. Moreover, this year was an anomaly because Bellflower made a one‑time payment of $6 million to pay off the outstanding balance on debt it had issued previously. In each of the other five years, Bellflower’s general fund revenue exceeded its expenditures by an average of $13 million. In other words, the board approved budgets that should have lowered the district’s available unassigned general fund balance, and instead the district underspent those budgets and continued to accumulate unassigned funds.

When the district presents its budget for an upcoming year, it has the opportunity to inform the board about the actual general fund balance. However, Bellflower has not presented its board with a clear picture of the district’s available funding. Instead, it has consistently overstated its current year estimated expenditures when projecting its year‑end financial position, which have not clearly shown that it was accumulating a significant and growing unassigned general fund balance. By doing so, it reduced its estimated year‑end general fund balance, making it appear to have fewer resources than it had. The district then used this understated year‑end balance as its beginning balance for the next fiscal year’s budget. Consequently, Bellflower has understated its general fund beginning balance to the board from $17 million to $24 million for each of the past several years, as Figure 9 shows.

Figure 9

Bellflower Has Consistently Understated Its Unassigned General Fund Balance at the Beginning of Each Fiscal Year

Source: Bellflower’s annual budgets and audited financial statements for fiscal years 2015–16 through 2020–21.

Figure 9 description:

Figure 9 is a column chart that shows Bellflower has consistently understated its unassigned general fund balance at the beginning of each fiscal year. Each column shows both the beginning fund balance reported to the board and the amount available but not reported to the board. Bellflower reported to its board beginning fund balance ranging from $22 million in fiscal year 2015-16 to $56 million in fiscal year 2020-21. However, Bellflower has not reported to the board amounts ranging from $17 million in fiscal year 2015-16 to $24 million in fiscal year 2020-21. Source: Bellflower’s annual budgets and audited financial statements for fiscal years 2015–16 through 2020–21.

Finally, the district has mischaracterized its general fund balance. As part of its budget presentation to its board, the district provides its anticipated general fund balance with amounts broken down by classification. For example, in June 2018 Bellflower’s proposed budget estimated that the ending total general fund balance for fiscal year 2017–18 would drop to $54 million and that only $13 million was unassigned. However, not only was the projected general fund balance inaccurate but the description of the fund balance was also inaccurate. In fact, the district’s audited financial statements for fiscal year 2017–18 show that the general fund balance rose to $73 million, with an unassigned amount of $62 million—significantly more than $13 million. Although Bellflower’s budget for fiscal year 2021–22 did not show significant amounts as assigned, its past mischaracterizations likely contributed to the district amassing the growing unassigned general fund balance.

Bellflower Did Not Provide Accurate Financial Information, Limiting Its Board’s Ability to Invest in Additional Services for Students

When we asked Bellflower’s associate superintendent for business and personnel services (associate superintendent) about the district’s budgeting practices, she stated that its approach is to present the board with the worst‑case scenario. As a result, Bellflower’s projections for its remaining expenditures in June each year have been far off from reality. With little time left in the fiscal year, staff present an unlikely scenario: that it will spend significant amounts in the last few weeks of the year. For example, as part of the fiscal year 2020–21 budget presentation to its board in June 2020, the district projected that it would end fiscal year 2019–20 with general fund expenditures of $168 million, resulting in its expenditures exceeding its revenue by $15 million. However, the district’s actual expenditures for the fiscal year were just $141 million—$27 million less than this worst‑case scenario—and the district had a $9 million revenue surplus. Only presenting the worst‑case scenario provides a one‑sided view of the district’s finances to the board.

By providing inaccurate information, the district has reduced the board’s ability to make informed decisions and provide effective leadership and oversight. District staff do not provide the board with year‑to‑date actual expenditures compared to its year‑to‑date budget when presenting the proposed budget and interim financial reports. Because this information is absent, the board is likely to remain unaware of Bellflower’s current actual financial position. The financial audit is the only document that provides an accurate picture of the district’s financial situation. Of the six years we reviewed, only in the most recent year did the district staff provide the board with a high‑level presentation of the fiscal year 2020–21 audited financial statements. Even so, although district staff accurately described the increase to the general fund balance and the year‑end balance in the general fund, it did not describe how these actual amounts were different from planned amounts presented in budgets and interim reports. Moreover, a best practice for public entities is to have the independent financial auditor present the audit report and a financial overview of the entity to give the board an independent view of the entity’s finances. Bellflower’s board would benefit from a similar practice—having the district’s independent auditor provide it a financial overview of the district—as well as requiring district staff to explain variances between the budgeted and actual amounts.

We question why, in the absence of a formalized reserve policy that sets a maximum target reserve, Bellflower decided to grow its unassigned general fund balance rather than invest in its students. According to Education’s dashboard, which reports the results of annual standardized testing, Bellflower’s students’ most recent test scores from fiscal year 2018–19 were near the state average for English language arts but were 17 points below the state average for math, indicating that Bellflower’s students needed additional assistance in math.According to Education’s dashboard, because of the pandemic, there are no testing results for fiscal year 2019–20, and testing participation for fiscal year 2020–21 varied. Over the last six years, Bellflower could have used some of its available funding to provide its students with extra math teachers, tutors, and additional programs to try to close this achievement gap. For example, given that the average midrange teacher salary for fiscal year 2019–20 for districts of Bellflower’s size in California was $84,000, the district could have added a math teacher to each of its 10 elementary schools and both high schools for under $2 million per year instead of increasing its unassigned general fund balance to over $80 million.

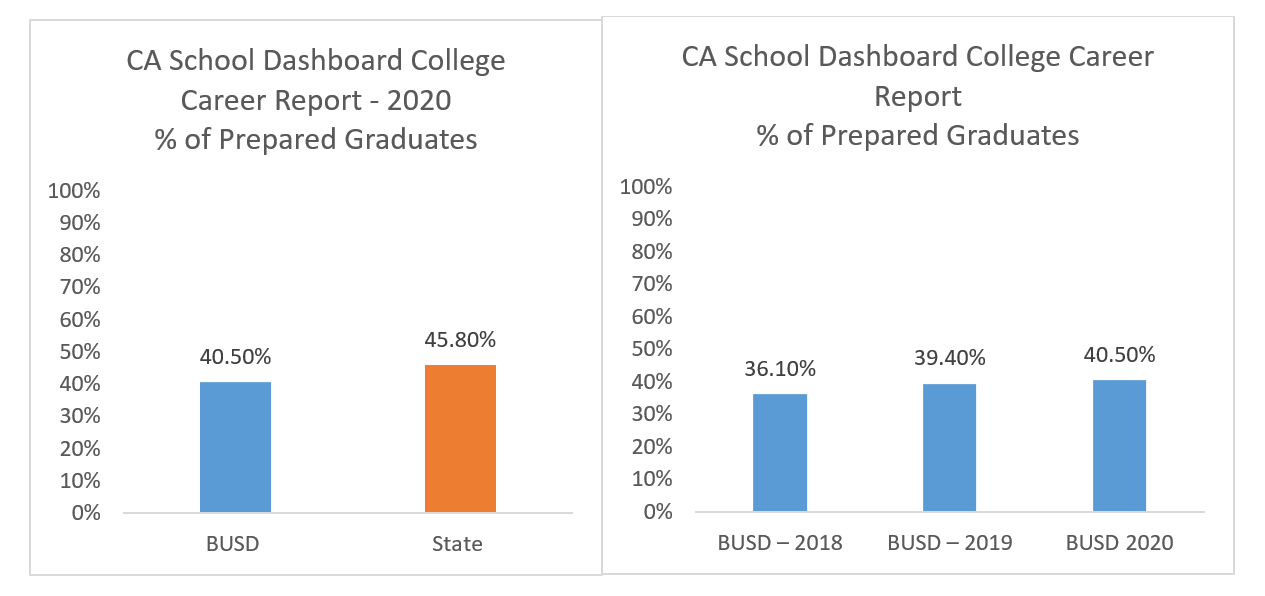

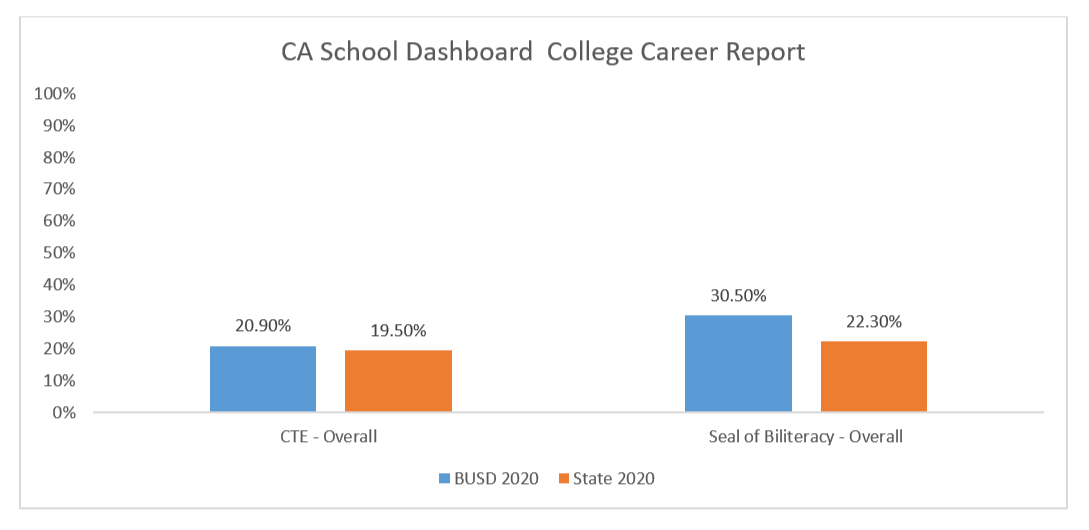

In addition to math instruction, Bellflower’s graduating students likely would have benefited from additional services over the past six years. Although Bellflower’s graduation rate in fiscal year 2018–19 was about 7 points higher than the state average, Education’s College and Career Indicator showed that only 39 percent of Bellflower’s graduating students were prepared for college or careers, which is lower than the statewide average of 44 percent. The district could have used its available funds to better ensure that its students were ready for their lives after high school. Further, Bellflower has not consistently provided required services to its students with disabilities and did not fully mitigate the effects of the pandemic on student learning. We find it problematic that Bellflower has amassed a growing reserve when it is not meeting the needs of so many of its students.

Bellflower Has Not Consistently Provided Required Services and Support to Students With Disabilities

Bellflower lacks sufficient processes to ensure that it consistently provides mandated services and support to students with disabilities. Federal law requires states to have policies and procedures to identify students with disabilities that interfere with their ability to learn and to offer those students special education services through an Individualized Education Program (IEP) so that they can access a free, appropriate public education. State law has delegated this responsibility to school districts. Figure 10 explains the process through which school districts must identify and assist such students. As we describe in Figure 4, there are two complaint processes at the state level: one through Administrative Hearings for resolving disputes about special education requirements and one through Education for determining whether districts are complying with special education laws. We reviewed complaint determinations that Administrative Hearings and Education made over the last five years to assess whether Bellflower provided adequate and consistent services to students with disabilities.

Figure 10

State Law Requires School Districts to Provide Certain Services to Students With Disabilities

Source: State law.

Figure 10 description:

Figure 10 is a flowchart that describes how state law requires school districts to provide certain services to students with disabilities. First, state law requires school districts to identify and assess the disabilities of students and then create an IEP that will meet those students' assessed needs. Second, once a student’s parents or guardian consent to initial evaluation(s) to determine whether a disability affects the student's ability to access an education, a district has 60 days to conduct the initial evaluation(s) and hold an IEP meeting. Then, using the evaluation(s), each eligible student's parents or guardian, teachers, and school district administrators (collectively referred to as an IEP team) meet to create an IEP that describes the how the disability affects the student's education; the student's current educational needs; the special education and related services the district will provide the student; and measurable annual goals to determine the student’s progress. After the IEP team has agreed on the contents of the IEP, the district must provide the special education and related services to the students. Then, at least once annually, the IEP team must meet to, among other activities, review the student's progress; determine whether the student is achieving the identified goals; and determine whether the IEP needs revisions. Source: State law.

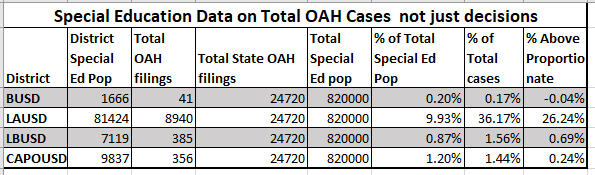

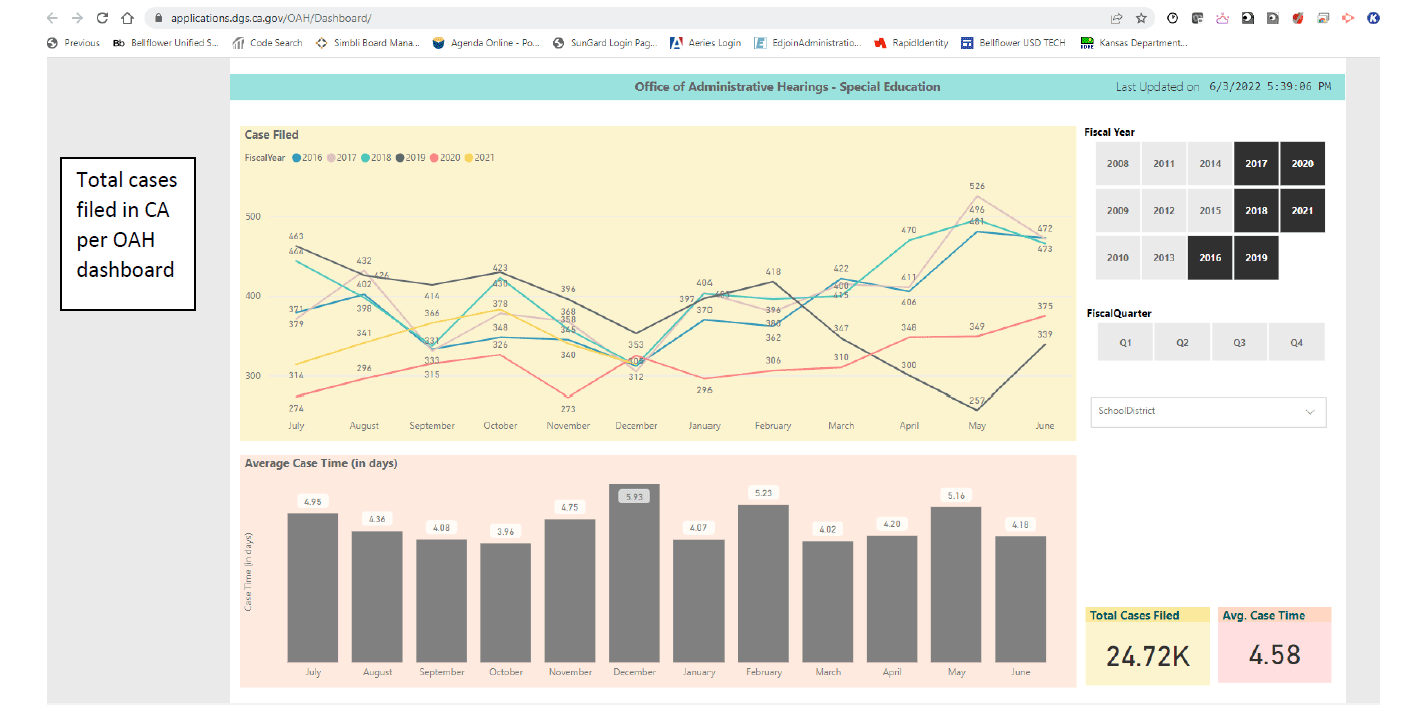

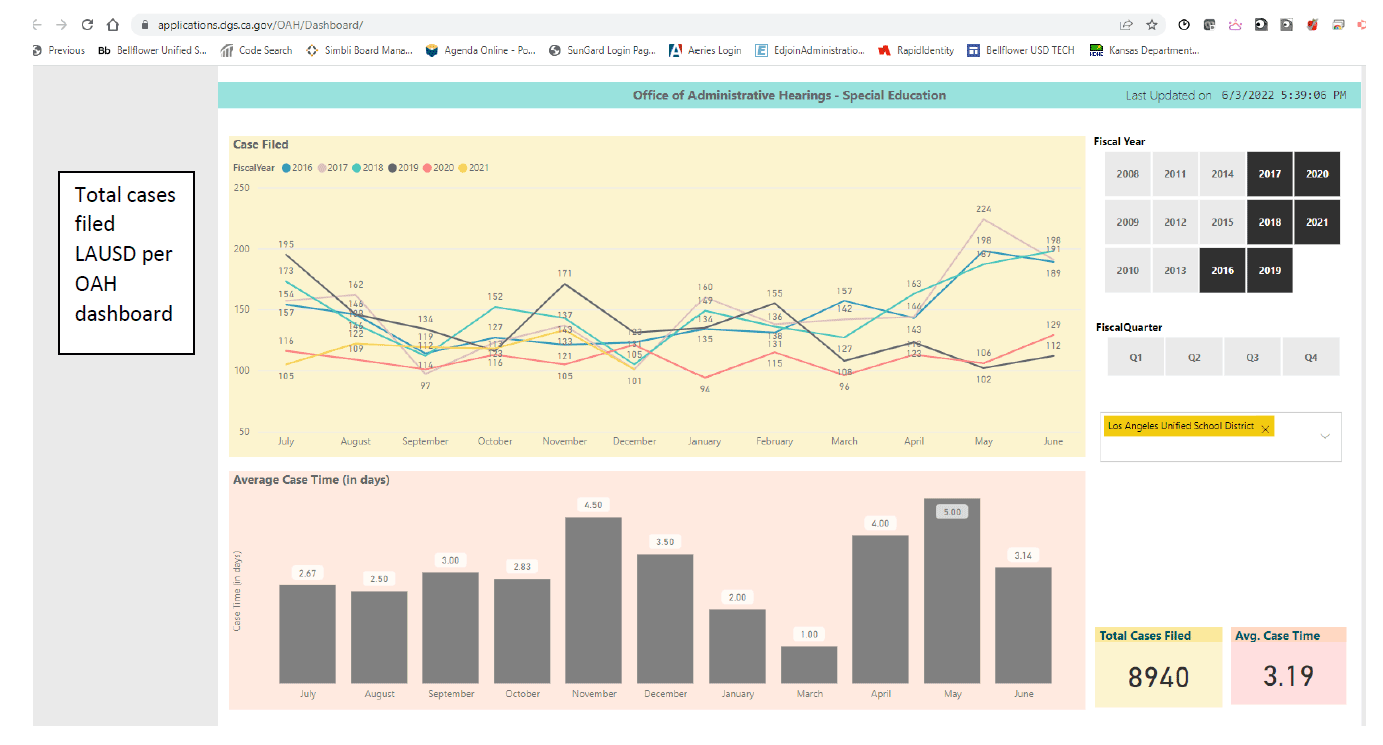

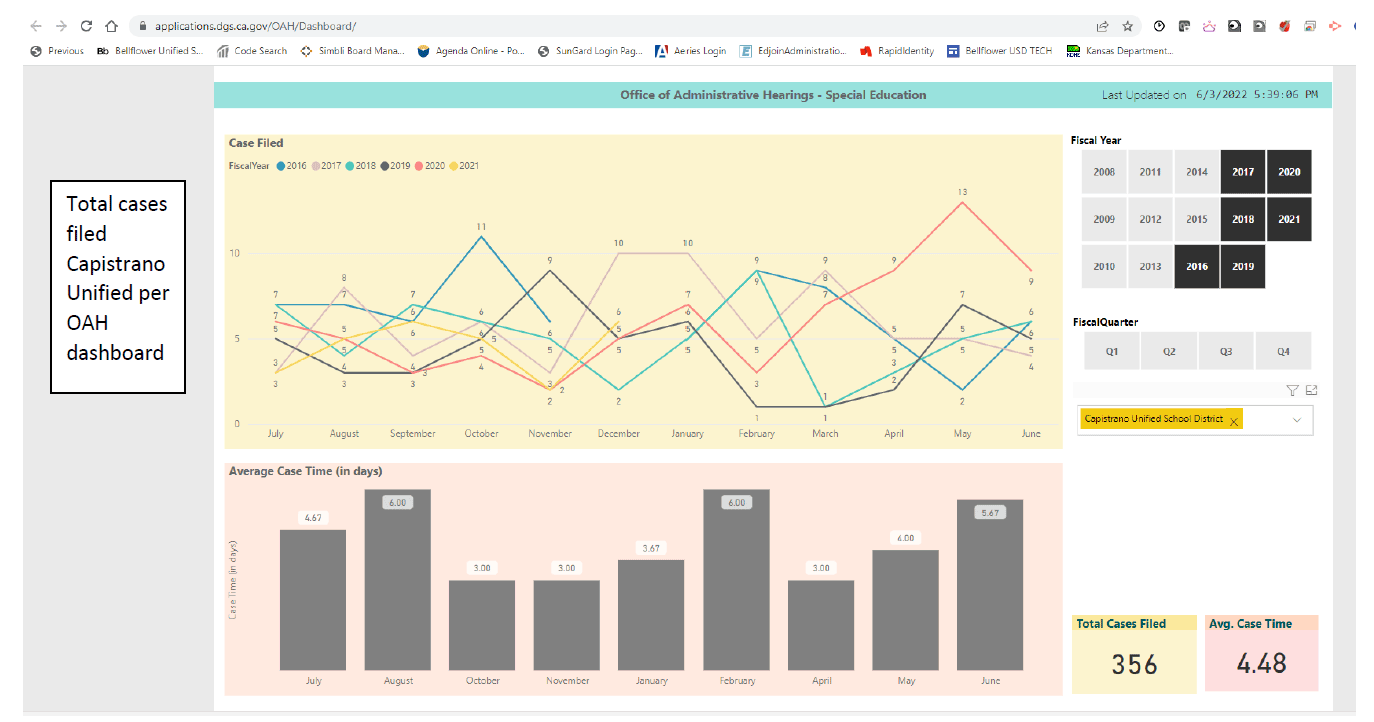

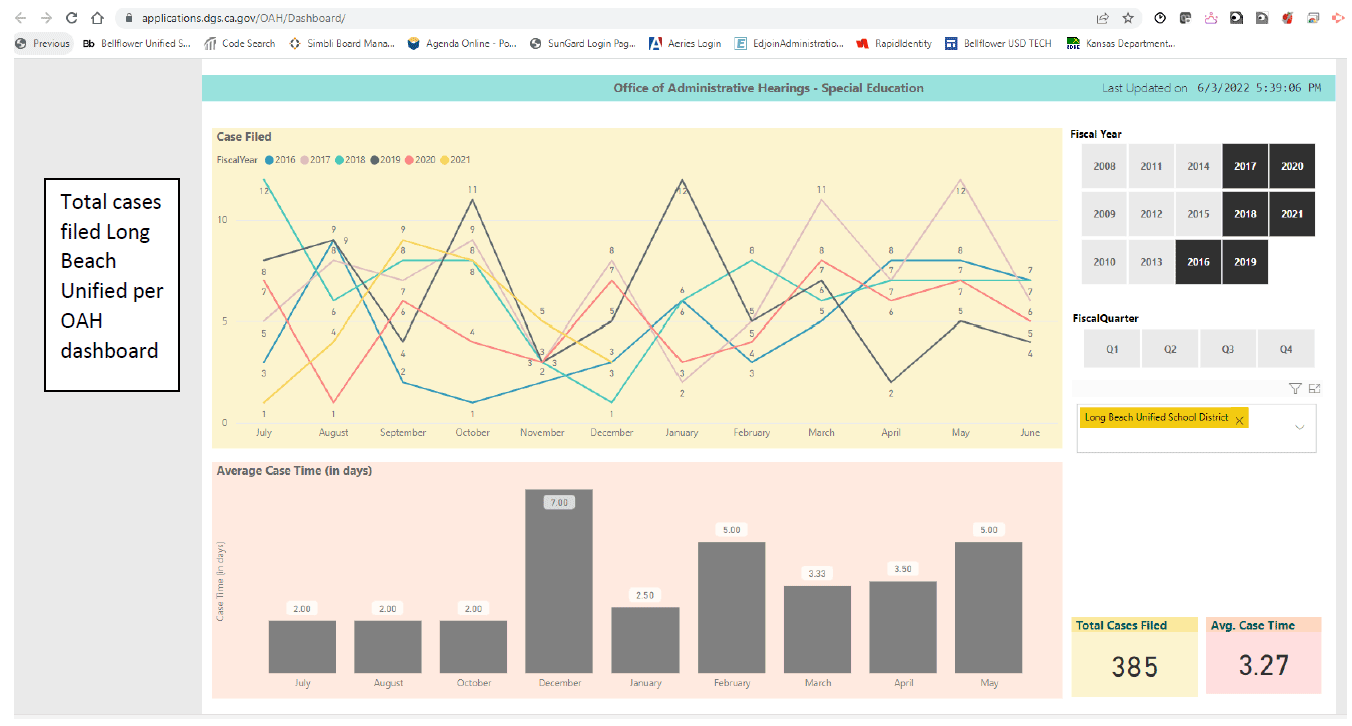

Over the past five years, Administrative Hearings has reached decisions on 15 complaints against Bellflower. As Figure 11 shows, Bellflower had about the same number of decisions issued by Administrative Hearings as school districts with much larger populations of students with disabilities. In fact, Bellflower accounted for 4 percent of all the decisions Administrative Hearings has issued since July 2016, even though the district represents just a fraction of a percentage of the 820,000 students with disabilities enrolled in California public schools. Moreover, Administrative Hearings determined that Bellflower failed to comply in one or more areas of special education law in 14 of the 15 complaints.

Figure 11

A Disproportionate Number of Administrative Hearings’ Special Education Decisions Have Involved Bellflower

Source: Administrative Hearings’ decisions for the last six fiscal years and Education’s cumulative enrollment data for students with disabilities for the 2020–21 school year.

* Cumulative enrollment for the 2020–21 school year.

Figure 11 description:

Figure 11 A graphic that presents the disproportionate number of Administrative Hearings’ special education decisions involving Bellflower. For the school year 2020-21, the cumulative enrollment of students with disabilities at Bellflower was 1,666. Over the last six years, Bellflower had 20 Administrative Hearings decisions issued. Bellflower has fewer students than that other school districts, but has more decisions. The Los Angeles Unified School District had cumulative enrollment of 81,424 students with disabilities in school year 2020-21, which was nearly 49 times as many students as Bellflower, but had 28 Administrative Hearings decisions issued over the last six years—just eight more decisions than Bellflower.The Long Beach Unified School District had cumulative enrollment of students with disabilities of 9,837 in school year 2020-21, which was nearly six times as many students as Bellflower, but only had 16 Administrative Hearings decisions issued over the last six years. The Capistrano Unified School District had cumulative enrollment of 7,119 students with disabilities in school year 2020-21, which was more than four times as many students as Bellflower, but only had 17 Administrative Hearings decisions issued over the last six years. Source: Administrative Hearings’ decisions for the last six fiscal years and Education’s cumulative enrollment for students with disabilities for the 2020–21 school year.

As Table 1 shows, Bellflower failed to conduct sufficient student assessments to determine whether the students required special education services in 11 of the complaints. Specifically, the district either waited for parents to request an evaluation or failed to conduct an evaluation despite having sufficient evidence that a student might be eligible for services. Administrative Hearings also found in four complaints that Bellflower did not conduct the required IEP meetings, and in eight complaints, Bellflower did not include measurable goals in its IEPs. Finally, Administrative Hearings often found the district did not change services or make accommodations for students who were struggling to access their education.

Table 1

Bellflower Consistently Failed to Develop IEPs and Conduct Sufficient Evaluations in Accordance With Special Education Laws

| COMPLAINT | DID NOT CONDUCT IEP MEETING AS REQUIRED | DID NOT PROVIDE REQUIRED SERVICES OR OFFER APPROPRIATE SERVICES | DID NOT INCLUDE MEASURABLE GOALS FOR IEPS | DID NOT CONDUCT SUFFICIENT ASSESSMENTS | VIOLATED PROCEDURAL SAFEGUARDS* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | X | X | |||

| 2 | X | ||||

| 3 | X | X | |||

| 4 | X | ||||

| 5 | X | X | X | X | |

| 6 | X | ||||

| 7 | X | X | |||

| 8 | X | X | X | ||

| 9 | X | X | X | ||

| 10 | X | X | X | X | |

| 11 | X | X | X | ||

| 12 | X | X | |||

| 13 | X | X | |||

| 14 | X | X | |||

| 15 |

Source: Analysis of Administrative Hearings’ decisions for the last five years.

* Procedural safeguards include an opportunity for the parents of a child with a disability to examine all records relating to their child, participate in meetings for their child, as well as the requirement that school districts provide families with written notice before taking certain actions and obtain written parental consent before conducting assessments or beginning special education services.

Administrative Hearings also noted that Bellflower provided conflicting or inaccurate evaluation results to parents, which, in at least one instance, did not include the required information to help the parents understand their student’s needs. Moreover, Administrative Hearings found that Bellflower sometimes did not perform sufficient assessments because it used outdated evaluation tools, conducted the wrong evaluation for a student’s age range, did not follow the required protocols for the evaluations, and relied on old IEP data instead of conducting a new evaluation. In its decisions, Administrative Hearings sometimes also identified the reasons for Bellflower’s failures to uphold special education law, as Figure 12 illustrates.

Figure 12

Select Quotes From Administrative Hearings Decisions That Show Reasons for Bellflower Not Upholding Special Education Law

Source: Administrative Hearings’ decisions.

Figure 12 description:

Figure 12 is graphic that presents five quotes from Administrative Hearings decisions that show reasons for Bellflower not upholding special education law: (1) “Bellflower’s failure to complete the IEP prior to the start of the 2019–2020 school year left student without an offer of placement and services”; (2) “Bellflower owed student the duty to evaluate him and failed in that duty”; (3) “More disturbing, by utilizing the 2015 cognitive scores, Bellflower predetermined student’s cognitive levels. By doing so, Bellflower relieved itself of needing to consider whether more challenging goals were appropriate”; (4) “Student’s teacher did not refer him for special education assessment because she believed student’s academic struggles were due to a lack of motivation rather than a disability. Bellflower thus allowed the subjective opinion of a staff member to circumvent its responsibility to thoroughly assess student”; (5) “Student had been reading at a fourth or fifth grade level since ninth grade, and was not making progress…Bellflower Unified still did not provide any interventions to help student access his education.” Source: Administrative Hearings’ decisions issued.

Education reached similar conclusions when it investigated eight complaints, containing 14 distinct allegations, that it received related to Bellflower for fiscal years 2016–17 through January 25, 2022. Separate from the complaint process involving Administrative Hearings, Education investigates written complaints it receives from parents who believe a school district has violated special education laws. In its investigations of Bellflower, Education found five instances in which the district had not provided the services in a student’s IEP and one instance where it failed to conduct a timely assessment after agreeing to do so at an IEP meeting. In total, Education found that Bellflower violated special education laws in seven of the 14 allegations it investigated.

According to its special education administrator, Bellflower attempts to learn from the Administrative Hearings’ decisions and from the investigations Education conducts. Despite this claim, when we asked him about whether Bellflower has done any broad analysis to identify systematic weaknesses in its provision of services to students with disabilities that have led to Administrative Hearings’ decisions, he stated that he was unaware of any analysis. He also stated that the district holds annual special education training for teachers on developing IEPs. Bellflower provided more than 1,000 pages of training documents to demonstrate its response to the issues identified by Administrative Hearings and Education. However, only a small number of these materials appear to have been created in response to specific Administrative Hearings’ findings. In addition, many of the materials are not dated and Bellflower did not provide sufficient evidence of who attended the more relevant trainings. Bellflower also did not demonstrate any efforts to analyze the types of violations that continue to recur at Bellflower.

When we discussed our concerns about Administrative Hearings’ and Education’s findings with Bellflower, it stated that it serves about 1,800 students who qualify for special education and that these complaints represent a small fraction of that population. We are concerned that this response indicates that Bellflower does not see its failure to provide legally required services as a serious problem. Although Bellflower is correct that the findings represent a small fraction of its students with disabilities, Figure 11 demonstrates that a larger percentage of its students had complaints decided by Administrative Hearings than students receiving services in other districts. Further, our review of those decisions and Education’s investigations found that Bellflower often failed to provide adequate and consistent services to students, violating federal and state special education laws.

Despite the need for Bellflower to provide critical and legally required services to its students with disabilities, it has not taken actions to improve its processes for doing so. Until it prioritizes providing consistent and adequate services to students with disabilities, these students are likely to continue to struggle to receive from Bellflower the education to which they are entitled.

During the Pandemic, Bellflower Did Not Adequately Mitigate Disruptions to Its Students’ Education

Bellflower reported in June 2020 that pandemic‑related school closures had greatly impacted its teachers, staff, students, and families, yet it did not take critical steps that might have mitigated some of these disruptions. The Governor issued an executive order in April 2020 that required each school district to complete a written report explaining the changes to program offerings it had made in response to school closures and identifying the effects that school closures had on students and families. Education named this report the COVID‑19 Operations Written Report, and Bellflower completed its district‑specific report in June 2020. In addition, instead of the standard LCAP, state law required each school district to complete a Learning Continuity and Attendance Plan for the 2020–21 school year explaining how it was addressing the impact of the pandemic on students, staff, and the community; the district’s plans for distance learning; and how it would ensure access to devices and connectivity for all students, among other information. To identify the actions that Bellflower took in response to the pandemic and the manner in which it communicated these actions to its community, we reviewed these two documents as well as Bellflower’s social media posts from the time period in question.

Instead of implementing a centralized districtwide approach to communicating with families after it closed schools in March 2020, Bellflower’s communications indicate that it relied on individual school sites and teachers to communicate with families and to determine how to provide instruction to students. Bellflower created a teacher resource website on March 23, 2020. The district also held meetings with school principals in the months after it closed schools, which the superintendent indicated were to discuss the resources available to teachers and other relevant topics while schools were closed. Although Bellflower announced on social media on April 1, 2020, that it would not resume in‑person learning during the remainder of the school year, that communication did not contain any information about how the district would conduct learning. After closing its schools in March 2020, Bellflower posted on its website a list of educational resources for students and families, as well as select low or no cost Internet options. However, the district did not provide any information about the district’s approach to remote learning for the remainder of the 2019–20 school year, instead indicating that teachers would be reaching out to students. Bellflower did not provide the public with information about distance learning during the pandemic until July 30, 2020, when it first presented a Frequently Asked Questions document (FAQ) on its website. According to the district, it then received a number of additional questions, causing it to update the FAQ on August 7, 2020. Some parents expressed their frustrations on social media about the district’s poor communication, including its FAQ.

Bellflower’s delayed response to Internet connectivity issues for its families further compounded the negative effects that the pandemic had on the education of many of its students. Although Bellflower had distributed 4,600 Chromebooks to students by June 2020, it was aware that some students still had connectivity issues. Specifically, despite identifying in its June 2020 COVID‑19 Operations Written Report that connectivity remained an issue for many families, Bellflower did not announce that it would provide Internet connectivity to families who requested it until July 2020, four months after its schools closed. After schools resumed in August 2020, Bellflower notified its principals that it would begin providing hotspots to school sites, but the district was not able to provide us with further information about how or when its school sites actually supplied families and students with Internet connectivity. When we asked the superintendent about whether Bellflower coordinated a large‑scale effort to identify and contact students and families who needed Internet connectivity and Chromebooks, she indicated that individual school sites determined how to accomplish this task. Given that Bellflower had $60 million in its unrestricted general fund balance at the end of fiscal year 2018–19, it had available funding to quickly provide the needed connectivity for its students.

Critically, Bellflower’s approach during school closures did not adequately identify or address barriers for its more than 1,800 English learners and their families. In May 2020, Bellflower added resources for English learners to its teacher resource website. In its Learning Continuity and Attendance Plan, Bellflower indicated that it conducted a survey in which parents who were not fluent in English expressed that they found Google Classroom—one of the district’s teaching platforms—challenging because it was not translated. When we asked Bellflower how it addressed this concern, the superintendent stated that all assignments were on Google so parents could have used Google Translate if they needed help translating their children’s homework during distance learning and that school sites and teachers were responsible for communicating to parents about this resource. However, Bellflower did not provide this information on its teacher resource site until September 27, 2020. It is unclear why Bellflower did not provide this information directly to families. Our review of the district’s website confirmed that it does not instruct parents to use Google Translate. The lack of translated classroom materials might explain in part why only 83 percent of Bellflower’s English learners showed up for distance learning, a lower percentage than the district’s average for all students of 87 percent.

Foster youth and students experiencing homelessness also faced challenges during the pandemic that Bellflower did not adequately address. After it closed schools, Bellflower contacted many of its families who have foster youth and students experiencing homelessness and identified several barriers, such as difficulty contacting teachers and not being able to access school meals, Chromebooks, and Internet connectivity. However, despite being aware of barriers as early as June 2020, when the district reported that 10 percent of its foster youth did not show up a single time for virtual school during school closures, Bellflower still had not implemented a plan to address these students’ attendance and participation issues when school began in August 2020. Bellflower wrote in its Learning Continuity and Attendance Plan, which its board approved in September 2020, that all foster youth and students experiencing homelessness would complete a needs assessment to identify barriers to accessing their education. However, it did not specify when students would perform these assessments or whether it would rely solely on the students and their families to self‑identify barriers. Bellflower indicated that someone from Child Welfare and Attendance—a specialized student support service that normally handles persistent student attendance or behavior problems—would contact the students. However, Bellflower was not able to provide any evidence of the assessments it planned to conduct in the 2020–21 school year or what actions, if any, it took to address the barriers the students identified. It is troubling that despite suspecting that these students would have educational barriers, Bellflower is unable to demonstrate that it took appropriate action in response during the pandemic.

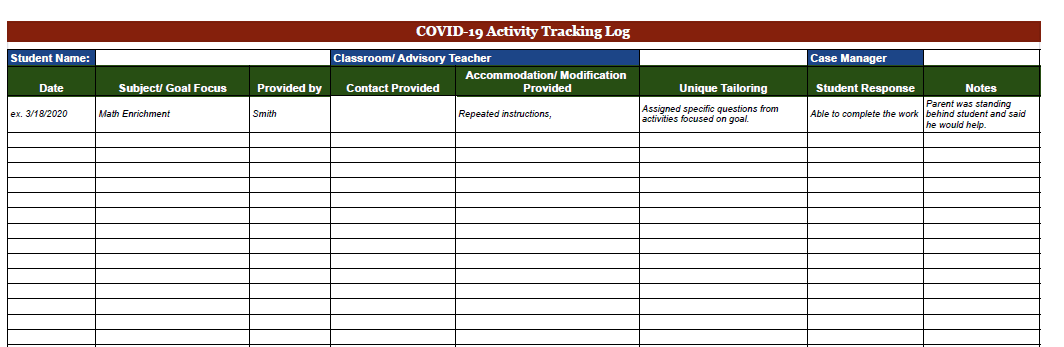

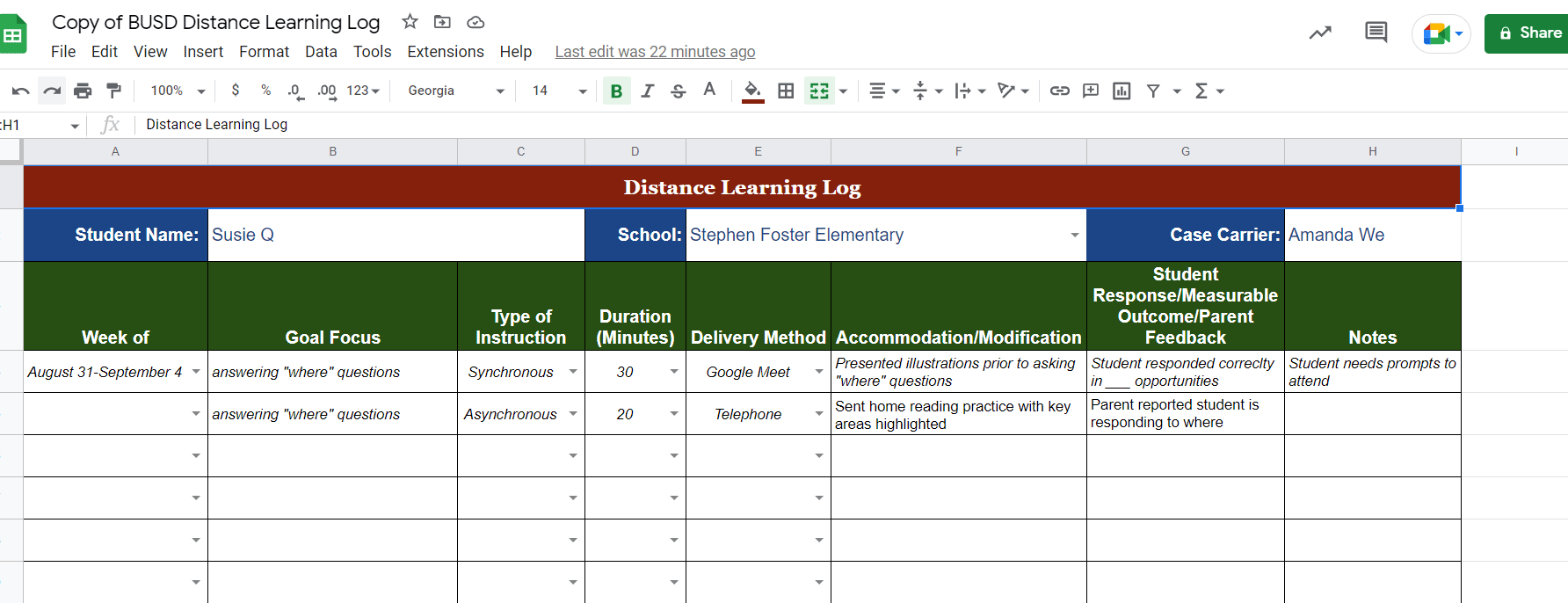

During school closures and distance learning, Bellflower also failed to adequately serve some of its students with disabilities. As we discuss in the previous section, Bellflower has not consistently provided required services and support to students with disabilities. The pandemic exacerbated these problems. In its investigations of complaints, Education found that during the pandemic Bellflower did not provide two students with required services outlined in their IEPs and delayed another’s student assessment. Similarly, Administrative Hearings found that from March 30, 2020, through June 4, 2020, the district provided a student with worksheets that had no educational benefit because they were below the student’s ability. Additionally, the district did not provide aide services to the student, without which the student had difficulty navigating the Google Classroom and video conferencing software. Consequently, Administrative Hearings concluded that the student missed opportunities to improve his grades.

Bellflower’s weak response to the challenges that the pandemic presented was not the result of a lack of funding. Like school districts throughout California, Bellflower received federal and state funds specifically to address these challenges. Table 2 shows the source and amount of pandemic‑related funding that Bellflower was granted and the amounts it spent. As of May 2022, the district had spent $16.7 million to mitigate the impacts of the pandemic. For example, it spent more than $4 million on supplies, such as face masks, plastic shields, and sanitizer to keep students safe while on campus. It also spent $1.7 million on computer hardware and equipment as well as $540,000 for data communication lines. We found that Bellflower complied with requirements to obtain and incorporate community feedback into its decisions for spending these funds.

Table 2

State and Federal Pandemic Relief Acts Have Allocated Bellflower $67 million

| COVID-19 RELIEF SOURCES | AMOUNT GRANTED (in millions) | AMOUNT SPENT (in millions) | AMOUNT REMAINING TO BE EXPENDED (in millions) | PERCENTAGE REMAINING | EXPEND OR OBLIGATE END DATE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning Loss Mitigation Funding | $1.0 | $1.0 | $0.0 | 0% | 6/30/2021 |

| Expanded Learning Opportunities Grant | 4.6 | 0.0 | 4.6 | 100 | 9/30/2024 |

| Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) | 9.7 | 9.7 | 0.0 | 0 | 5/31/2021 |

| Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER) I | 2.7 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 41 | 9/30/2022 |

| ESSER II | 10.8 | 3.3 | 7.5 | 69 | 9/30/2023 |

| Expanded Learning Opportunities Grant (Includes allocation from Education's ESSER II funding) | 1.2 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 100 | 9/30/2023 |

| Assembly Bill 86—In-Person Instruction Grant | 4.5 | 0.0 | 4.5 | 100 | 9/30/2024 |

| Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Fund (GEER) I | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 100 | 9/30/2022 |

| GEER II | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 100 | 9/30/2023 |

| ESSER II | 24.4 | 0.0 | 24.4 | 100 | 9/30/2024 |

| Expanded Learning Opportunities Grant (Includes allocation from Education’s ESSER III funding) | 2.2 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 100 | 9/30/2024 |

| Assembly Bill 130—Expanded Learing Opportunities Program | 2.7 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 100 | 6/30/2023 |

| Reopening Schools Fund* | 1.9 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 58 | 7/31/2022 |

| Senate Bill 117—COVID-19 LEA Response Funds* | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0 | Not identified |

| Miscellaneous* | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 50 | 9/30/2022 |

| TOTALS | $67.2 | $16.7 | $50.5 | 75% |

Source: Education and Bellflower’s financial systems and funding information.

* Bellflower provided information for these pandemic-related sources of funding.

The district has committed $7.5 million of its remaining unspent balance of $50.5 million in pandemic‑related funding to goods and services it has not yet received. According to Education, state and federal spending deadlines require Bellflower to spend $1.1 million before the end of July 2022, $2 million more by September 2022, $2.7 million by June 2023, $9 million by September 2023, and the remainder by September 2024. If it does not do so, it may have to return the funding. At its October 2021 board meeting, Bellflower adopted a plan to spend some of this funding. This plan indicates that the district intends to spend nearly $5 million to address lost instructional time including tutoring and summer learning; $11 million on ensuring the safety of in‑person learning, which will include upgrades to technology at its schools; and the remaining $8 million on interactive hardware, temporary counselors, and resources for learning. However, Bellflower’s plan does not connect any of its planned actions to goals in its LCAP or Learning Continuity and Attendance Plan, and the plan does not provide detailed metrics it will use to monitor whether the actions it is taking address student needs. Additionally, Bellflower’s plan does not indicate the extent to which the district intends to spend its funding to address the unique needs of its English learners, foster youth and students experiencing homelessness, or its special education students despite the educational disruptions that these groups faced because of the pandemic.